Project Overview

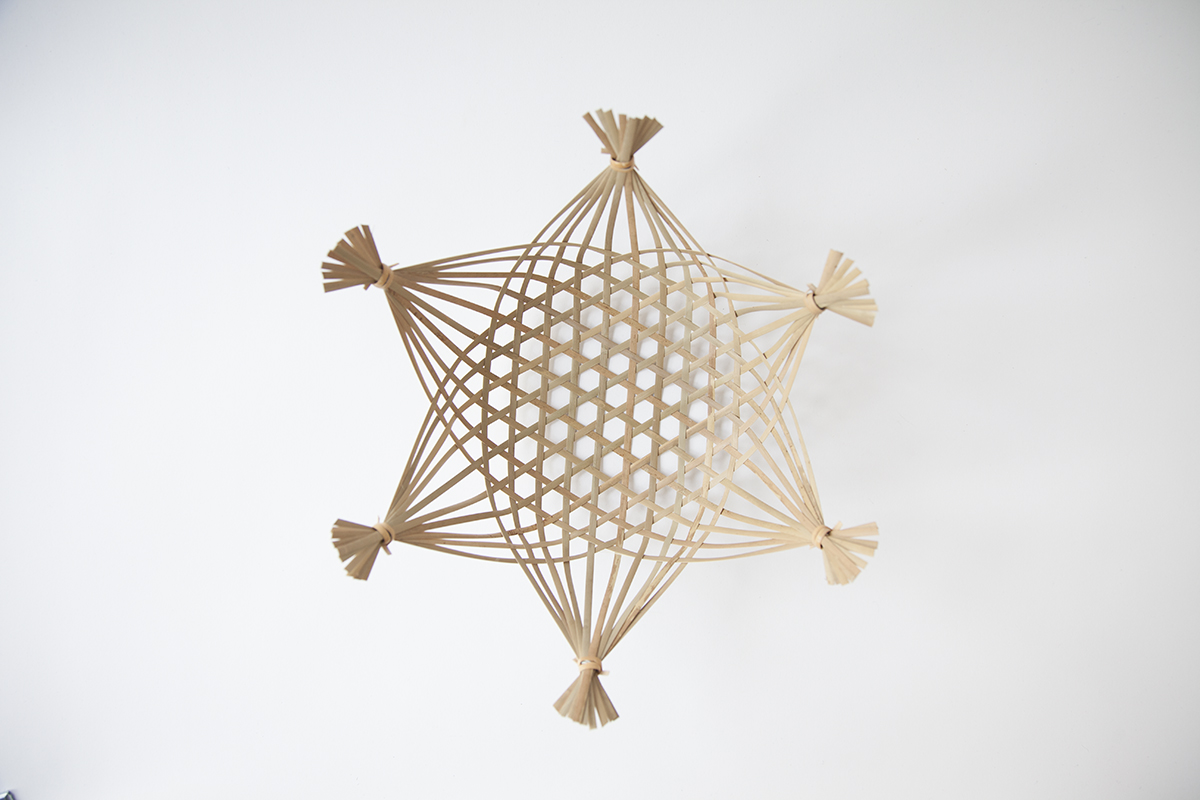

Rigs and Jigs is a reconstructed portable picnic basket for two, in form and ideology. It makes tools that make the objects for eating. In this case: the objects for eating a familiar Taiwanese meal, San Bei Ji (Three Cup Chicken). The picnic basket consists of a three part mold to make two eating bowls, a chopstick hand-planing jig to make two pairs of chopsticks, a three part lid mold and two part mold to make three containers to hold rice, San Bei Ji, and pickled cucumbers. It is accompanied by a palm bristle brush to clean wood shavings, a scoring knife, a leveling square, a hand pull saw, and a hand planer.

Problem

The project takes on the disjointed nature of contemporary industrial design; a field in which material production is outsourced, dematerializing the object from its design and production process. It attempts to reconnect the “product” to its process of making, by presenting the tools that make tools beautiful, as final objects.

Design Process

The conception and realization of this project lives in the space between craft and design. It began by setting the table, choosing a meal that was familiar to me in order to think of the specific tools for eating it. This familiarity was crucial to a mode of thinking that would not decenter the body and its knowledge, a line this project carefully walks.

The design process for this project worked to materialize a philosophy of industrial design through the objects and tools used to make the picnic basket, emphasizing the equal importance of the tool, the maker, and the final object. These principles reciprocally inform one another, rather than taking place linearly, and the understanding of material is practiced through craft, made legible through design. The overlap creates a more profound knowledge of the body in relation to making objects. For example, to make a chopstick jig by setting a guiding profile angle and shaving it down with a hand plane, and to make a porcelain mold to cast and extract its multiples are both practices of understanding how materials move differently as they exist in different states. These practices have been honed for generations. To affirm the value and historical significance of material process deflates the absurd scale of industrial production, and amplifies the necessity of craft.

Shaping the Future of Food

Both my Taiwanese and Italian family look to food as love, a lesson in practicing rituals of care in making objects and meals. The Picnic Basket to Build a Picnic Basket asks us to see food and objects similarly, to raise our appreciation and value for both. I asked, “how might the love that surrounded food in my family home be introduced to the hegemonic means of production, bringing empathy to the process of making?”. In asking the user to make their own objects for eating, I am also asking them to consider where their food comes from and to understand the systems that allow them to eat, even if they have not grown or harvested the food themselves. This piece equates process and product, and in so doing, hopes to lead to a consideration and understanding of the true worth of each morsel we consume. This small shift in perspective can shape the future of food, destabilizing the place of industrial production in the things we use and eat.

About the Practice

Thomas Yang is a Taiwanese and Northern-Italian designer, with a background in industrial and object design. His craft is derived from culture, memory, and inherited techniques; it is based in a philosophy of care enacted to extend the life of the objects he makes and offer respect to their living environments. Existing in the cross section of craft and design, his practice explores their intersection as a means of finding balance. His work has become a love letter to daily use, material, and deliberate detail through its exploration of hand-making methods.