Earlier this year social media timelines were inundated with three-by-three grids — each image in the grid a rendered variation of a text prompt internet users had entered into the text-to-image generator DALL-E Mini. These images depicted prompts that ranged from the benign, like “pug Pikachu” or “ice cream boots”, to the deranged, with popular entries like “Barney the dinosaur on trial for murder at the court” or “Gordon Ramsay sinking in quicksand” making their rounds on the viral meme carousel. DALL-E Mini, which is based off of OpenAI’s DALL-E 2 software and has since been rebranded to Craiyon, made the powerful image generating tool accessible to the masses. Remixing images and patterns gathered from all corners of the internet, powerful text-to-image generators like Craiyon, DALL-E 2 and Midjourney empower users to render untapped imaginaries.

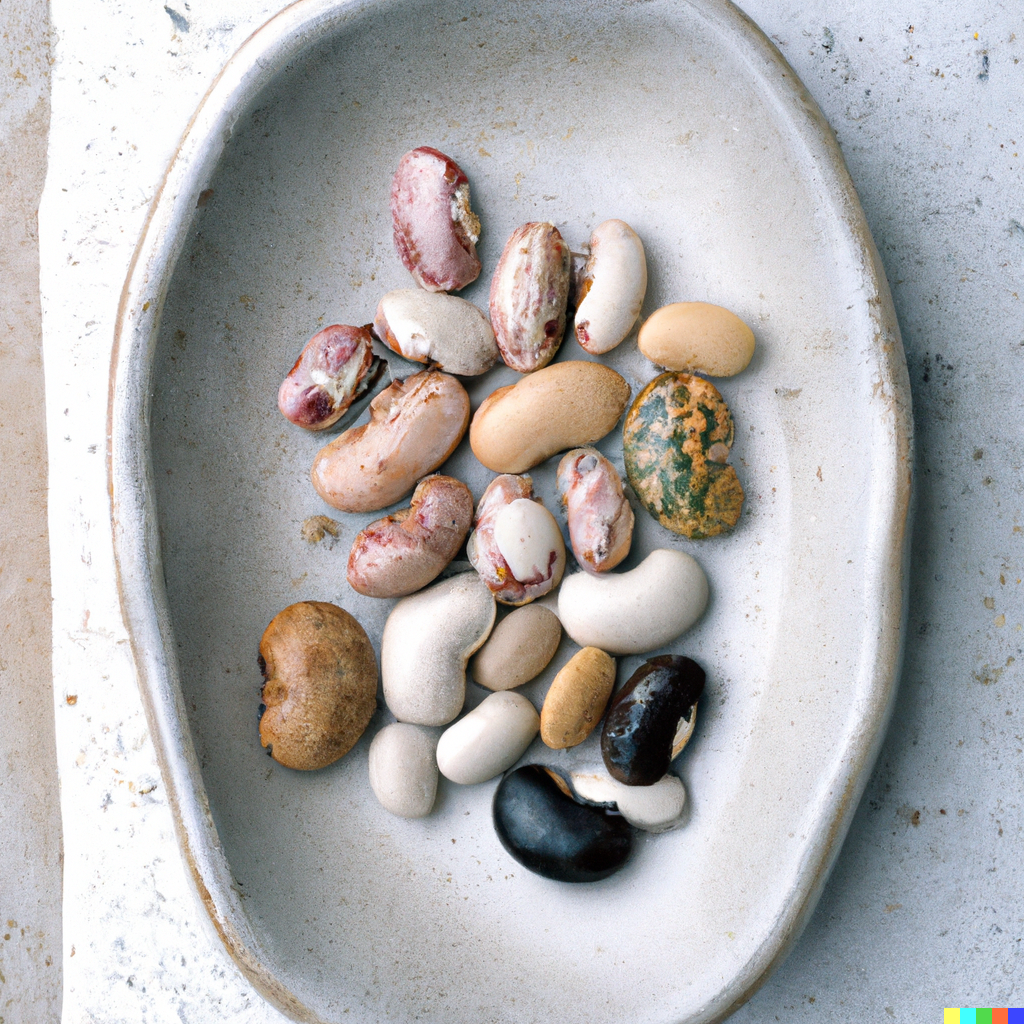

Meech Boakye first began using DALL-E 2 to create images for a speculative cookbook. They had previously experimented with AI models in hopes of creating a cookbook in which all the text would be generated by AI. Having learned about the tool from a video posted to social media by comedian and visual artist, Alan Resnick, Boakye signed up to be part of the Artist Onboarding Program, an initiative by OpenAI that gave a select group of artists early access to the full DALL-E 2 software. The Portland-based artist, whose practice centers around gardening, foraging and food preparation, saw the powerful software as an opportunity to tease the boundaries surrounding our conceptions of food, flavor and consumption. Like many chefs, they had a bank of ideas they wanted to try their hand at, and DALL-E 2 seemed like an easy way to begin broaching some of those ideas. Their early concoctions included mouthwatering entries like “beets roasted ‘til soft, soft apples cut thin, shaved fennel and fennel fronds, lemon zest” and “hand-churned butter, whipped and piled into a mound, decorated with flower petals and crushed up pistachios”— images that could just as easily be found on their Instagram account, where they post vibrant photos of meals they’ve made for themselves and of their experimentations in fermentation and bioplastics.

While the uncanny valley has served as a hurdle for scientists and technologists in computer imaging, for those attempting to navigate an increasingly digital world, it can serve as a survival mechanism

Boakye isn’t the only artist using the software to experiment with food— in a blog post documenting how other participants in the Artist Onboarding Program had used DALL-E 2, OpenAI highlighted how restaurateur Tom Aviv had used the software to design the way his Miami restaurant would plate dishes, in this case, a Picasso-inspired chocolate mousse, ahead of its opening. However, in their personal experimentation, Boakye found DALL-E 2 to be a more useful tool for subjects outside of food, “The physical process of eating food and preparing food is very grounding for me, it connects me to the land around me and my body,” they told MOLD in a recent phone interview, “Eliminating the physical process and consumption of the food afterward, and instead getting only the satisfaction of picturing it, there was a sort of ennui.”

Instead, Boakye gravitated towards using the tool to create speculative art objects, using DALL-E 2’s photographic representation tools to experiment with material, scale and lighting to create richly textured, photorealistic images. A recent project shows variations on hands holding amorphous sculptural objects that appear to be made of silicone, another shows a series of smoothed, fat inflatable flowers, plopped in desolate desert landscapes.

DALL-E 2’s world-building potential has captured the imaginations of designers, artists, architects, and meme-makers alike. The artist Alexandra Daisy Ginsburg, who has previously worked with artificial intelligence to design pollinator-friendly landscapes, has used the image generator to create paintings from the perspective of bugs. Other internet users are quite literally attempting to peer into the future, entering prompts that ask DALL-E 2 to image predictions as to what future societies might look like. With a few strings of words, DALL-E 2 users are able to easily modify existing images, convincingly combine two different input images, and create variations on input images that retain certain aesthetic properties or features.

While DALL-E 2 has provided users with the tools to image alternate worlds, there are drawbacks to its utopias. Neural networks, trained with millions of images scraped from the internet, reproduce and therefore reinforce existing biases like racial and gender discrimination. For Boakye, this meant implementing workarounds like manually typing in “held with black hands” in order to navigate the model’s tendency to represent human forms as white. With the roll-out of DALL-E 2, OpenAi has been careful to place limitations on the types of images its beta testers can produce by “removing the most explicit content from training data” and “preventing photorealistic generations of real individual’s faces, including public figures”. However, as OpenAi continues to expand access to its DALL-E 2 tool (recently granting access to 1 million individuals on the waitlist), experts continue to warn of the potential dangers of placing the tool in more people’s hands. In an interview with Wired, Maarten Sap an external expert OpenAi tapped to review potential problems noted that whenever there was a negative adjective associated with a person in an entry, results largely returned non-white people in it’s representations. Another anonymous expert expressed concern that DALL-E 2 was rolling out a technology that would “automate discrimination” at all.

“I think for a lot of people, images are evidence,” says Boakye, who is concerned about how DALL-E 2 will contribute to our current shared reality, fractured as it already is by the proliferation of conspiracy theories, fake news, and toxic online forums, “I think the ability to easily create images, with a relatively low barrier to entry — you don’t have to know how to use Photoshop or editing software, you can create endless images with a relatively low barrier to entry that have the potential to convince people of the beliefs they already held true.”

Innately, telling the difference between what is real and what is not has always been essential to human survival and evolution. Within the human-to-machine relationship this instinct comes into play as the “uncanny valley”, a phenomenon initially used to explain the uneasiness that arises when humans encounter robots that are too life-like. While the uncanny valley has served as a hurdle for scientists and technologists in computer imaging, for those attempting to navigate an increasingly digital world, it can serve as a survival mechanism. As the boundary between our perceptions of what is real and not continue to be blurred, Boakye cautions that these tools for image-making should not be approached as an apolitical entity, particularly when at the hands of the state, “At the end of the day, I don’t know if the net gain of a tool this powerful will be neutral. The only thing I can know is that it exists and we are here now, much faster than I could ever anticipate. Out of curiosity, in anticipation, I am trying to understand rather than resist.”