This is the second part in Wayfinding, a series on the history and design of cookbooks.

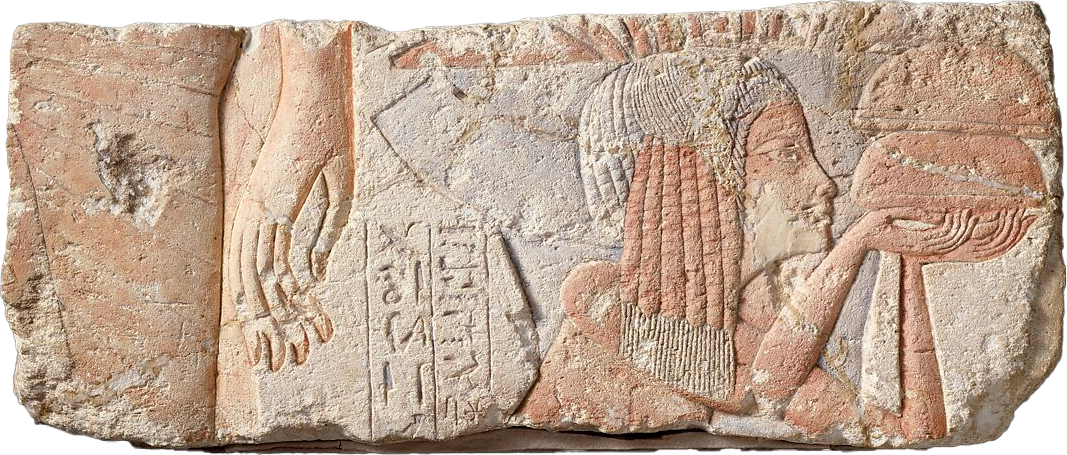

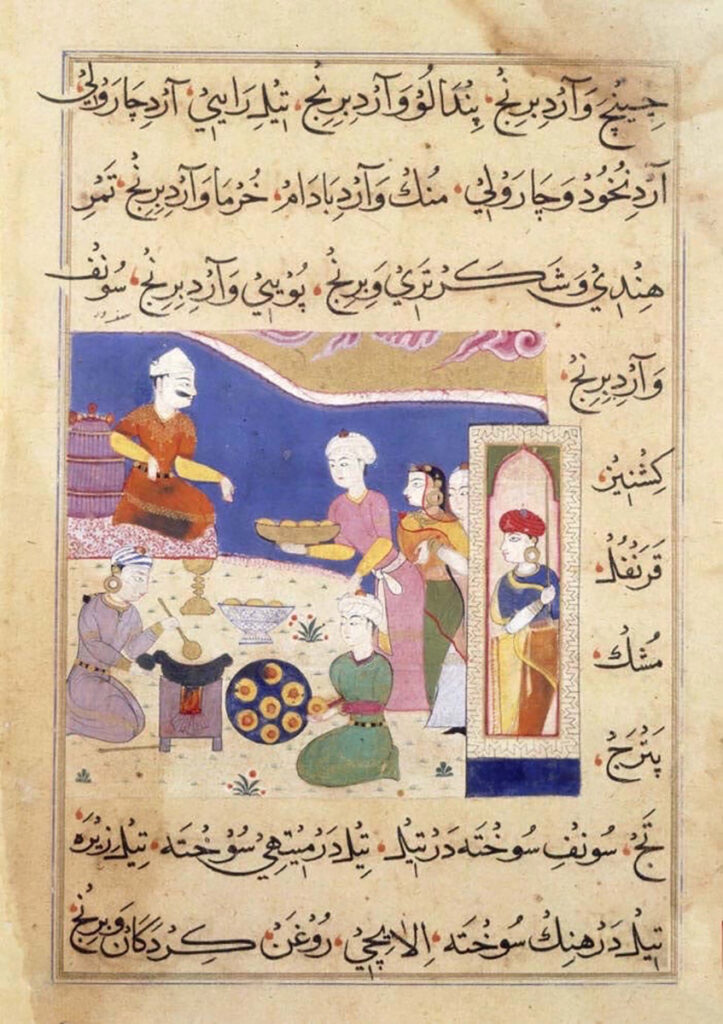

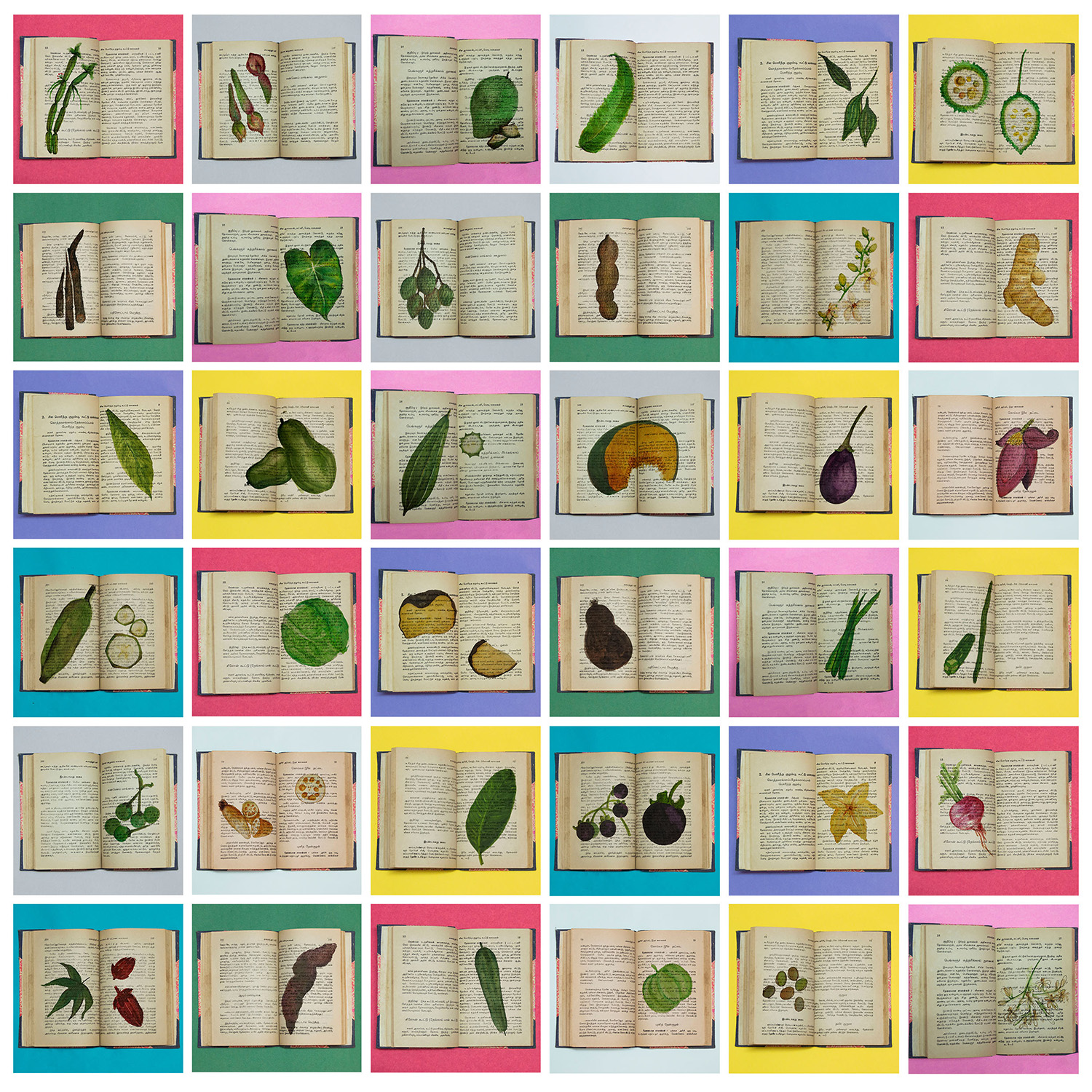

In cookbooks, the format of recipes shifted over time, and the changing formats orient us to the dish in different ways: One asking us to wayfind through our own memories, and the other through replicable instructions. Early recipes in many cultures, including in China, India, and across Europe, were often formatted as paragraphs. Some do include measurements, but the process of preparing the dish is written as a narrative, not a list.

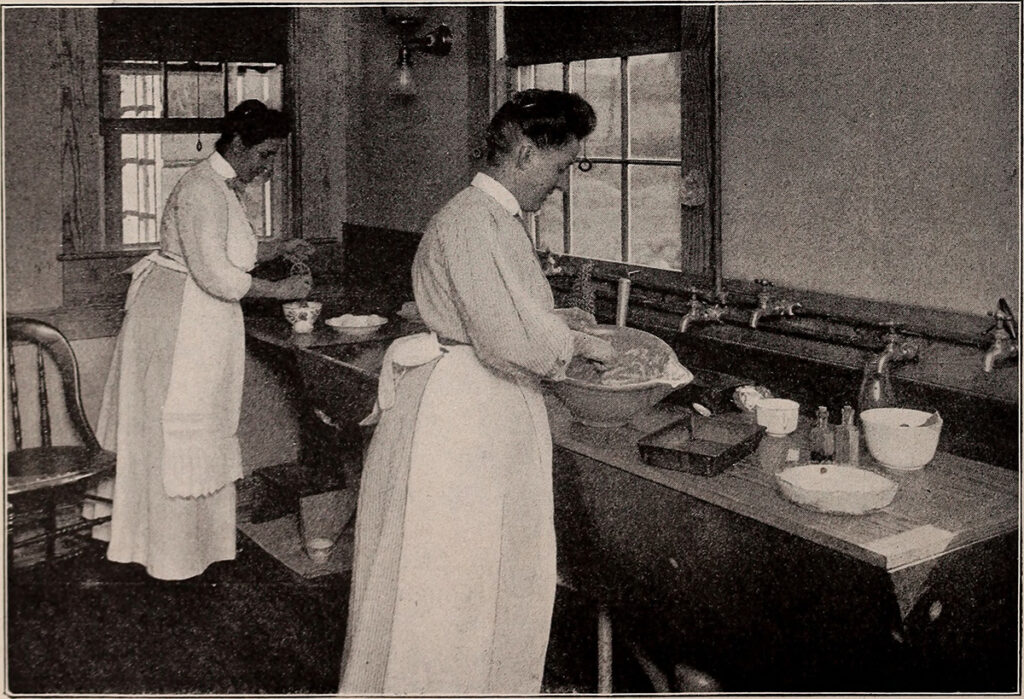

Juli McLoone, Curator of Special Collections at University of Michigan, describes this aspect of cookbook history as one of proximity and mobility: it’s the history “of figuring out how to write instructions for someone who is not next to you, she says. “Because if we go back even farther to the household manuals of the 18th century and 17th century, they’re not really expecting you to rely upon this as your sole source of instruction.” Instead, the book was meant to complement hands-on learning, taught in person to you by someone in the same room.

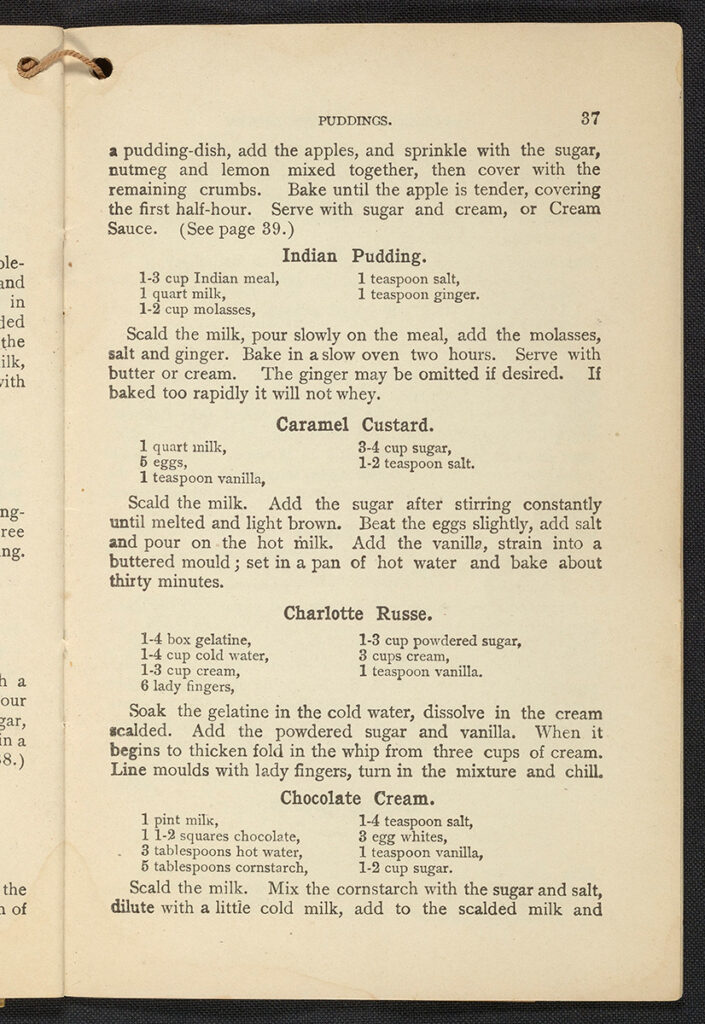

Our familiar modern recipe format, of ingredients and measurements, followed by discrete steps, became popular in the 19th century as the movement between social classes resulted in the need for shifts in teaching cooking and dining as a set of social etiquettes. This modern format was codified in the U.S. by Fannie Farmer’s 1896 book, The Boston Cooking School Cookbook, who famously gave us the volume-based measurements we still use in American cookbooks today. However, Farmer’s not the only author to use measurements plus steps (Mrs. Beeton’s in England is another, both preceded by Hannah Glasse). The Boston Cooking School Cookbook was used to teach cooking in a more classroom-style, standardized way, and it radically transformed how we interact with recipes and our food itself.

Steps and ingredient lists made even unfamiliar recipes accessible—whether or not the person sharing the recipe was there, in person, to teach you. Suddenly, the history of the person in the room, helping you wayfind, could be anywhere.

Within a couple decades, more and more cookbooks adopted this model, and recipes with steps and lists became ubiquitous in the 20th century. According to King, Chinese cookbooks, once more narrative, shifted towards measurements and steps by the 1950s. Before that, “you have to already know how to cook in order to be able to understand a lot of those recipes… Often no measurements, often a handful of this or some of that.” But even after, the guidance is pretty basic: “it assumes some knowledge already.”

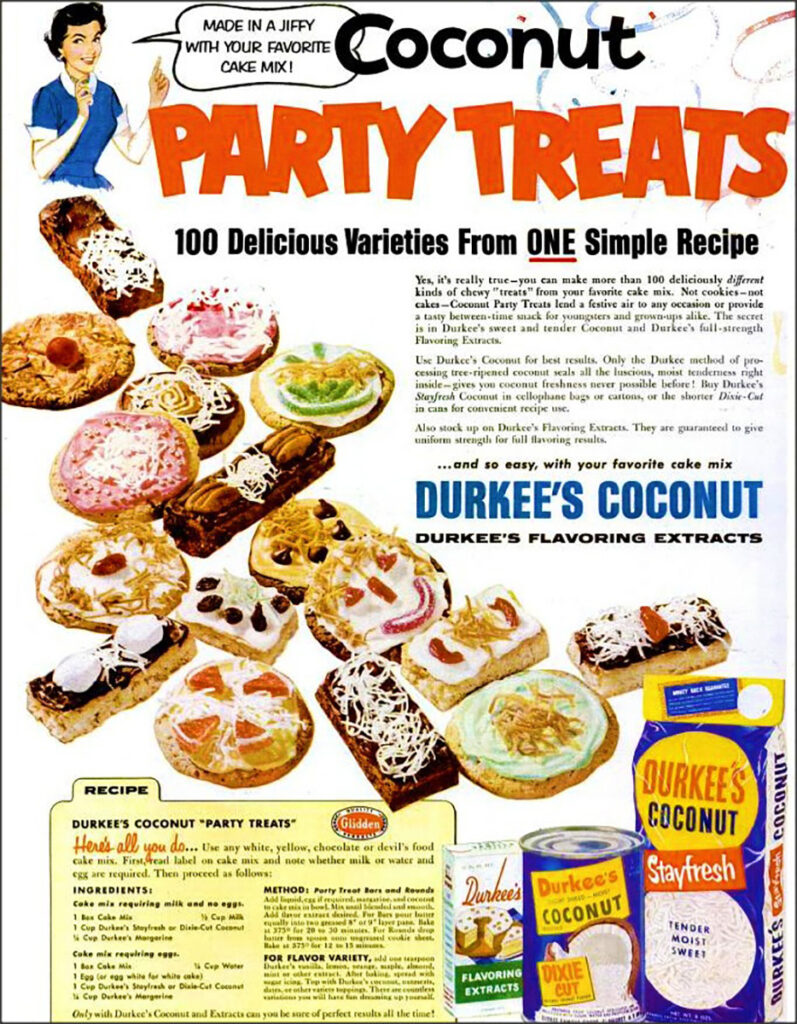

McLoone notes that standardized recipe formats came about in a world with “increasing enthusiasm for being scientific, for being efficient, for being industrial.” Advertisements for food products proudly show off factories and smoke stacks: A nod to efficiency and modernity (as opposed to today’s advertisements framing mass-produced foods as artisan, handmade, or high quality). “So it’s a very different aesthetic and very different sort of value set…but you still have that same appeal, like you want to be part of what is of this moment.”

But there’s another key motivator for commercial publishers, too: Profit. If specific measurements and steps are what is selling, publishers will keep printing them.

More and more women became literate around the time of the Industrial Revolution, and more and more books were printed more cheaply, bringing a gendered component to social mobility and the changing format of books. King notes that “cookbooks presume literacy” and through most of Chinese history, most women were not literate, except for elite women, and “they’re not doing the cooking anyway.” The cookbook, then, could not become widely useful as a cookbook until the people who would be using it could access it.

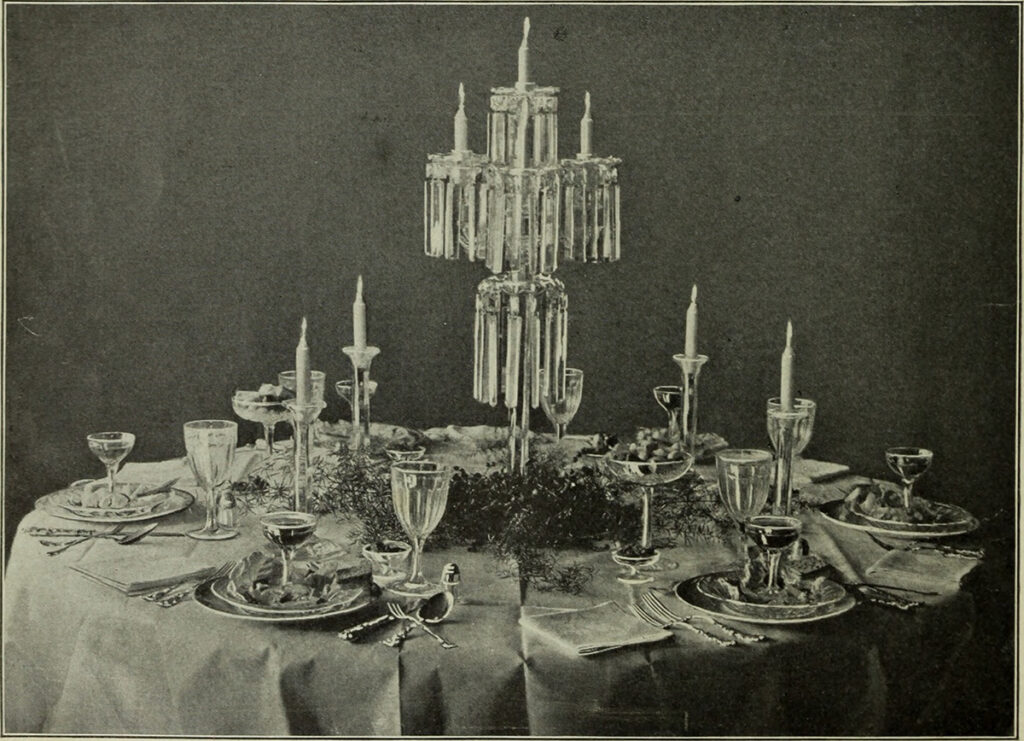

In the U.S., culinary instruction and cookbooks were used as part of the larger Progressive-era ethos, where public libraries were founded in part as sources of “improving” books for the community. As people moved away from their families and to the cities, organizations like the Boston Cooking School taught women the domestic arts.

But McLoone notes that these cookbooks are also one piece in the larger Progressive-era Americanization puzzle: the cookbook as aspirational object, of what we want to be seen as eating rather than a record of what we do eat, also extends to what we think other people should be eating too.

The late 19th- and early 20th- centuries saw several waves of immigration to the US, and as immigrants settled in the US, cookbooks and cooking schools became part of larger assimilation efforts, guiding new Americans’ wayfinding efforts through directing their diets. In other words: Here’s what Americans eat, and here’s what you’ll eat if you want to be American too.

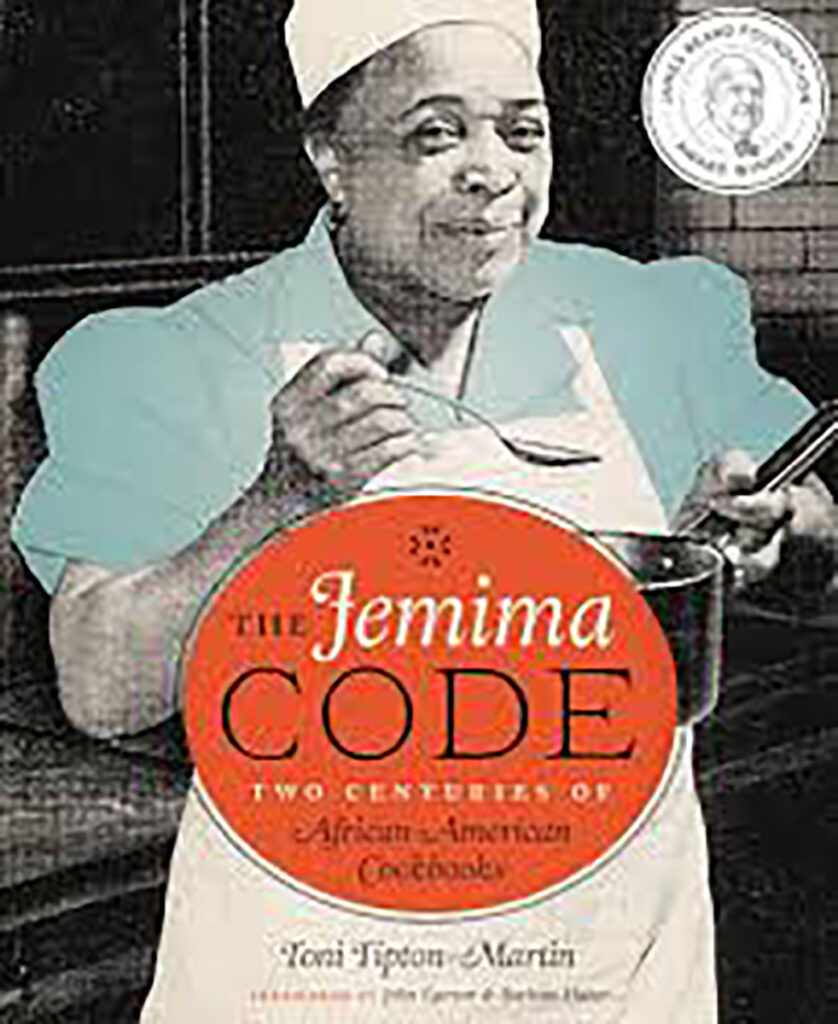

An increasingly globalized world also meant a convergence of cookbook histories: more books available to more people more cheaply, and in more places. But not everyone was included equally: There is a rich history of Black cookbook authorship in the United States, (see Toni Tipton Martin’s Jemima Code), but many of the authors did not receive the praise (or, presumably, the funding) of their white counterparts. It’s a parallel path to American culinary history generally: Black folks have been forced into kitchens and out of sight, shaping what American cuisine is without the ability to publicly participate in the discourse around it.

Format and Function

So how does a change in format change how we cook? Are we ultimately restricted by the clear boundaries of steps and ingredient lists, or is this format somehow freeing?

If the standardized recipe format is made to instruct someone who’s not there, perhaps this is why we treat the recipes in cookbooks as immovable: Yes, there are some techniques that are critical to get on the nose (like with baking, or canning). But adding 1/2 tsp of pepper flakes versus 1 tsp? That’s purely subjective.

Online, the internet is rife with examples of people swapping out half the ingredients then complaining of the results: But it’s a phenomenon we hear about less often with feedback for cookbook authors. Is it the physicality of the book in a digital age that makes us treat the recipes as sacrosanct?

With the modern reliance of measurements and steps, we have perhaps lost that familiarity and sense of play with our food, and our courage to mix up a recipe (and to play around often enough to know how to do it). Perhaps this is why we struggle with what can be substituted and how: because many of us have lost the internal compass that would be built up through hands-on experience.

King says, “I think in order to develop that sensibility, you have to have cooked in order to know, for example, what acid to substitute for what.” Perhaps by giving ourselves permission to play, and viewing our efforts and learning and fun rather than a potential for failure, that internal compass can again begin to chart its proper course.

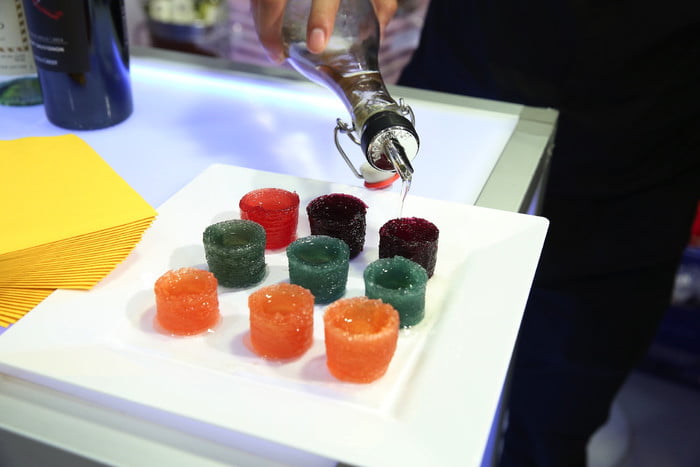

While it limits us in some ways, perhaps it frees us in others: Because with a teacher who can be there even when they are not, you can also learn about dishes you otherwise could not. And this opens up an invitation to explore traditional recipes through this replicable lens.

Godbole notes that “there’s so much missing from the media landscape in cookbooks” when it comes to Indian food, but she’s noticing changes. In the past, recipes used to be just for popular dishes: “now we’re seeing a lot of content around traditional recipes: these [recipes] have always been there.” More readers are curious to learn and explore foods unfamiliar to them: and rather than giving them yet another riff on a popular favorite, we can teach technique as well as a dish. As Godbole says, “I’m going to give you the tools for how to take control of what you’re eating. And this is how you can manage that, or navigate that. And I want you to have the freedom.”