Wayfinding is the first part in a series on the history and design of cookbooks.

The history of the cookbook sits at the intersection of the personal and the public: Of formats, of fields, of the many ways our small daily choices ultimately shape the world and the record we have of it. To truly understand cookbooks is to engage in wayfinding: of concurrent path making and path taking, and a convergence of many histories well beyond the story of the books themselves.

Cookbook history is rooted in fields beyond cooking, and its paths branch out in dozens of directions. It’s a path whose bricks are laid from many other thoroughfares: Finance, medicine, agriculture, and domestic etiquette, to name a few. And it is an embodied history: One that asks us to experience the book’s products, and the book itself, through our senses.

It is rooted in the handwritten works that walk the path alongside, and often merge with, the printed books created for public consumption. To understand cookbooks, we must approach our classifications and binaries about publishing with a critical eye: To instead think of the winding path as one where “both/and” is as much a part of the story as “this or that.”

The history and future of the cookbook is not one single walkway, but rather a convergence of many. And it’s a path whose bricks we each lay, actively, as we walk it: Our wayfinding is informed by the many threads that weave themselves through its story, and the meaning and experience each of us brings to that story through our own choices, each time we eat, or cook, or engage with a cookbook.

Look To The Side To See The Middle

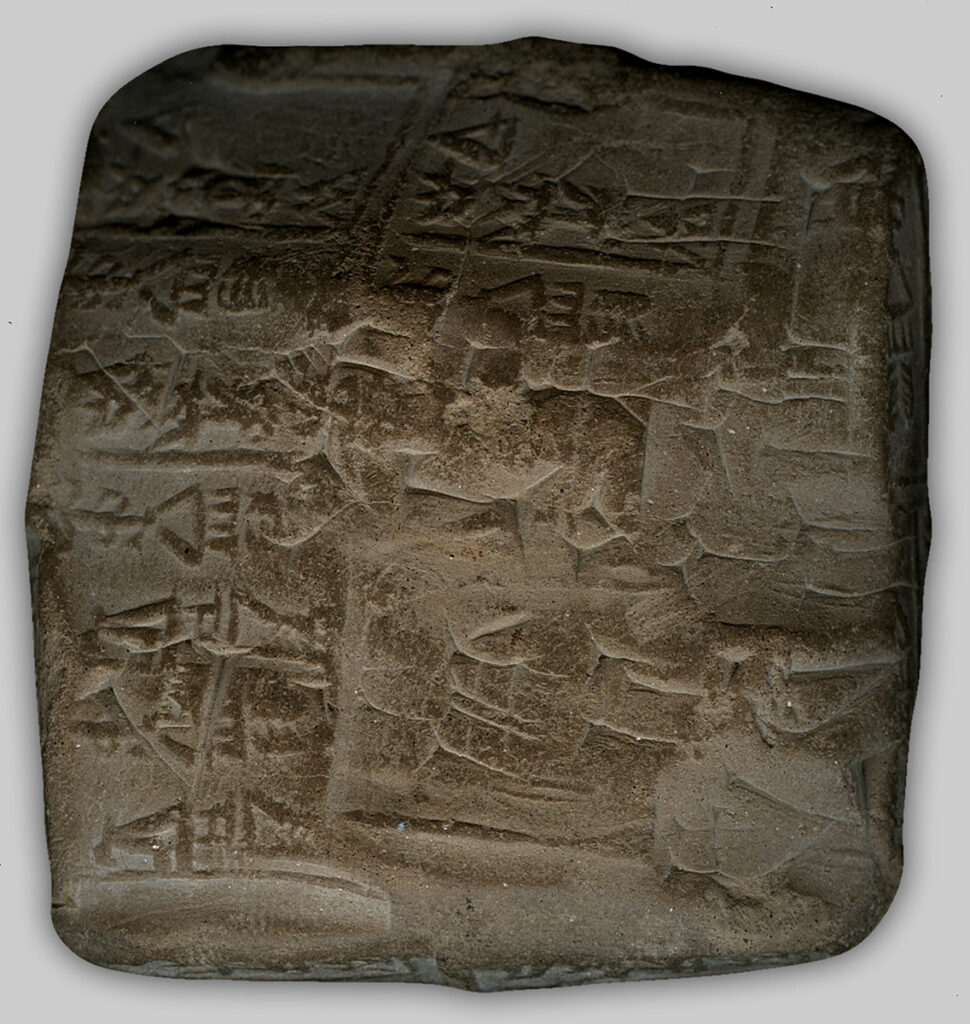

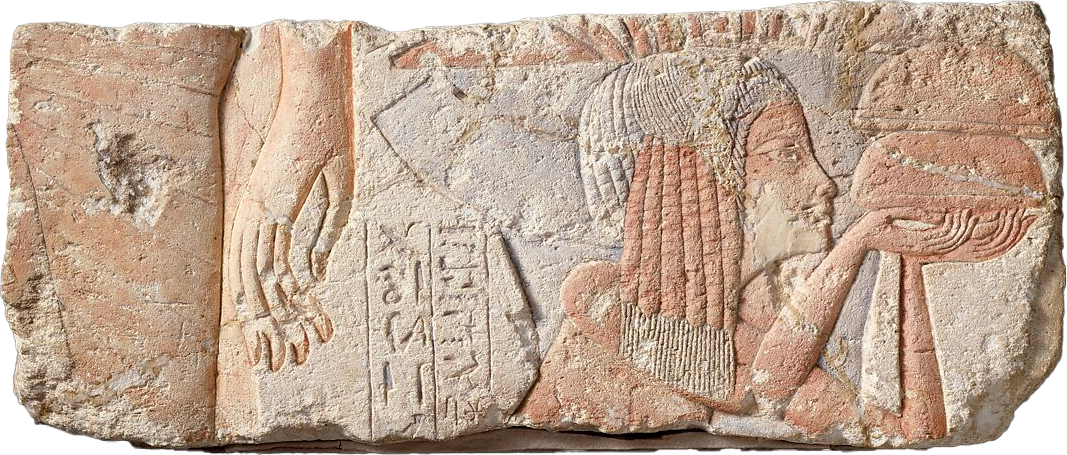

Food, as subject, appears just about as soon as writing systems do, but food as subject in these early systems often meant the business of food: in receipts on cuneiform tablets, for example. But the business of food and books stretches beyond the financial records we have for food as a product, and onward to the making of books themselves.

Prior to the 15th century, all books were handwritten books: each letter written by hand, each stitch bound by hand, the pages of vellum treated and stretched and finished by hand. Each book was incredibly labor-intensive and thus, also incredibly expensive.

The introduction of moveable type printing in 1450 brought new possibilities, but also presented new problems: As with many technological innovations, people were initially wary, so printed letters were made to look like manuscript letters so the new books were visually familiar. After all, wayfinding is harder if your next signpost is so far away that you can’t see it.

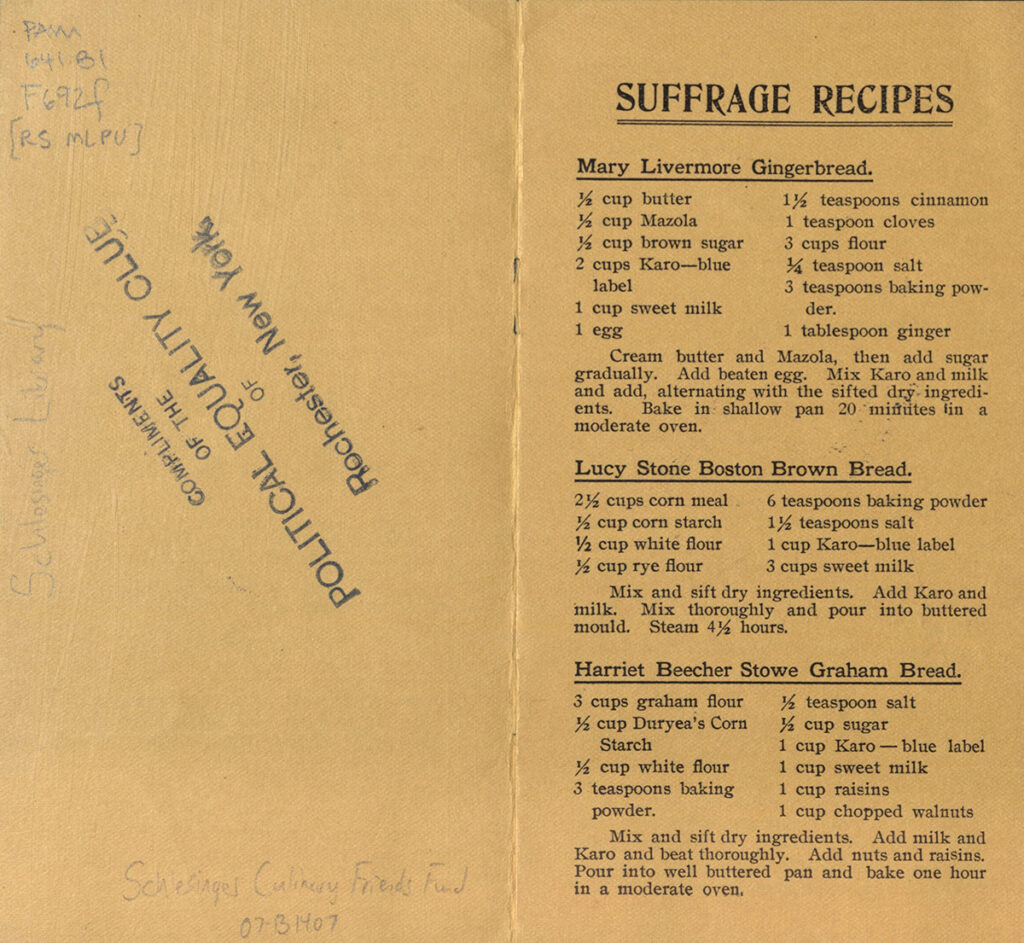

In this series, I’m defining a printed cookbook as a published book with recipes in it: and the farther we go back in the history of printing, the less often they appear (though they do appear). Like looking at the night sky from the corner of your eye to better understand the nuance of the stars, looking at cookbook history asks us to look at the histories that surround it. To find this history, we must look to the side to see the middle.

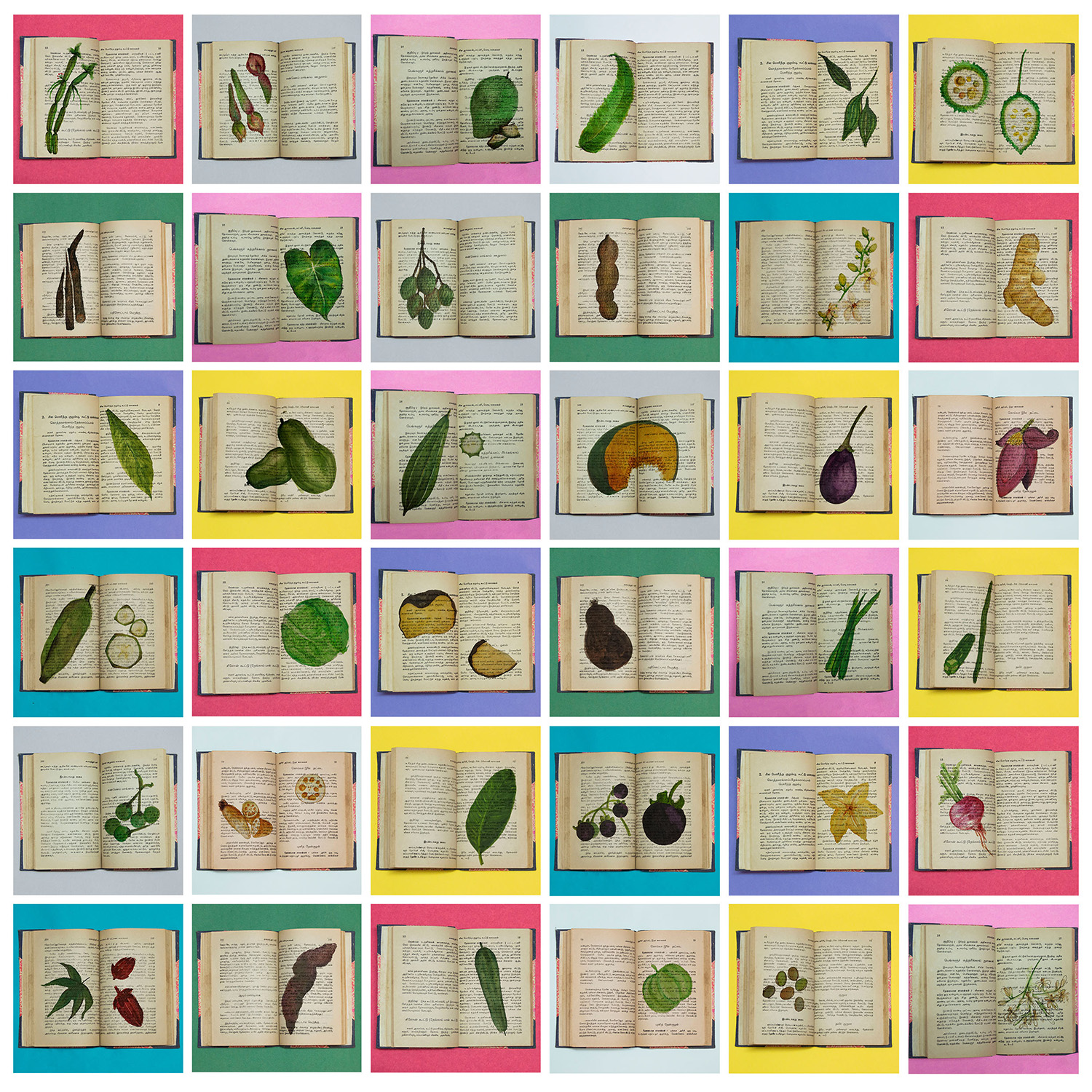

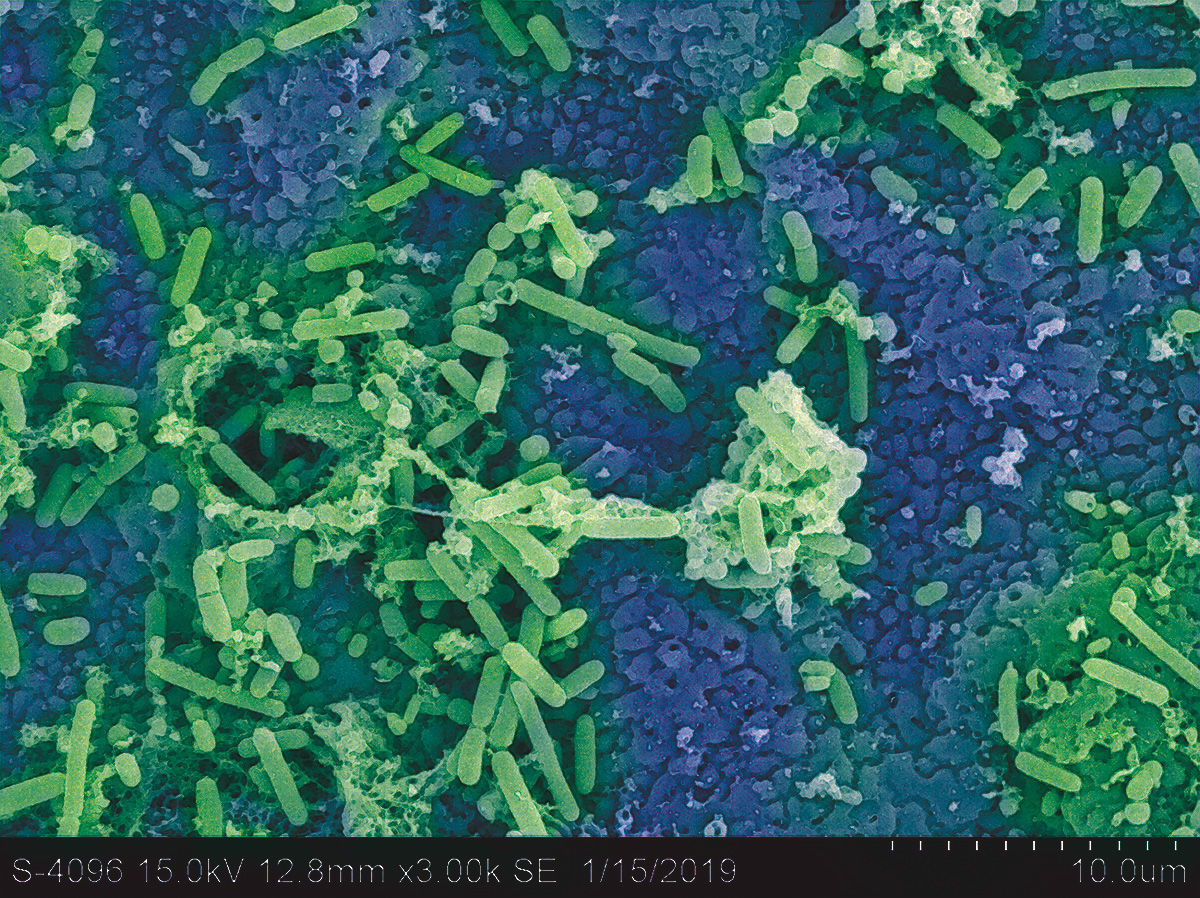

Around the world, culinary writing and culinary practices are rooted in medical and agricultural traditions, and a publishing industry bounded by the realities of bookmaking technologies as well as cost and literacy rates.

Much of the information we have prior to the 16th and 17th centuries is not so much the food itself or how to make it, but the perceived benefits of the food, as medicine, product.

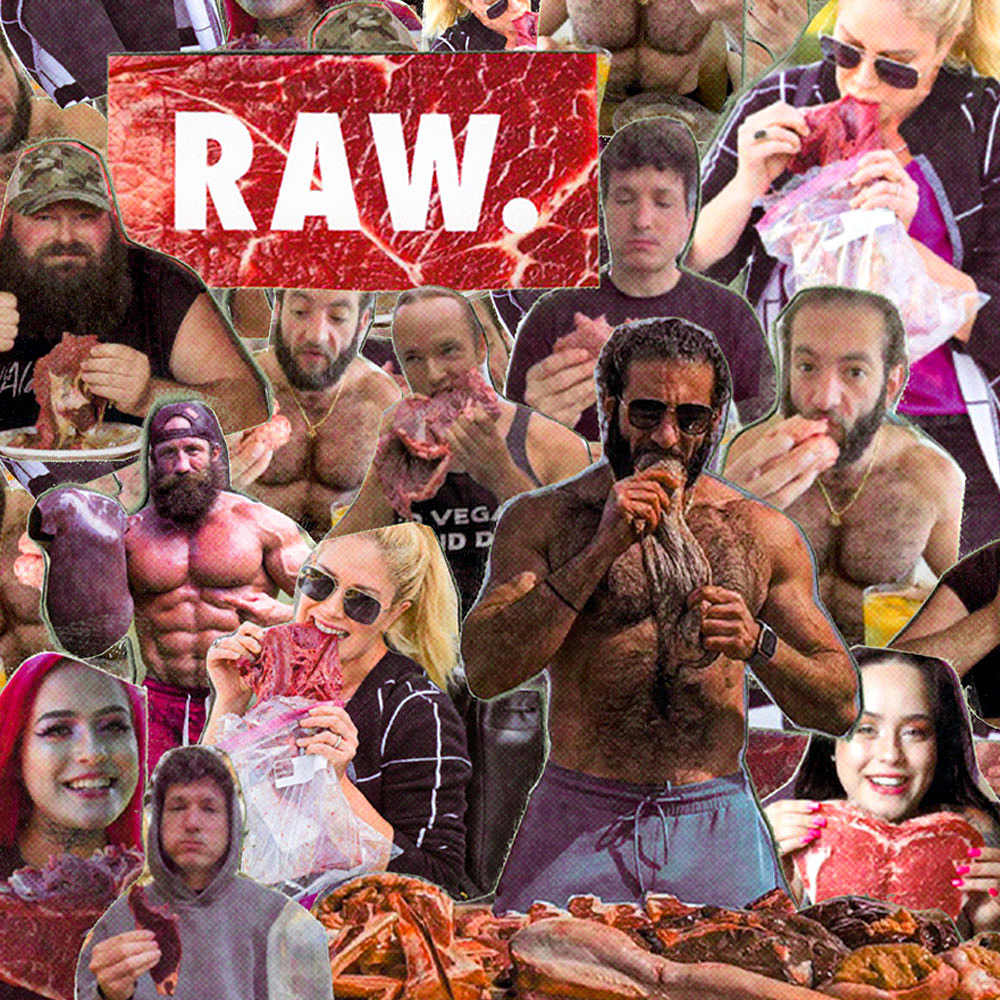

Going farther back in time requires us to expand our definition of cookbooks and to look outside books that contain recipes: Historian Ken Albala notes that, for early printed books, much of the culinary material we have is self help and nutrition books. “What I found most fascinating about it is it revealed a lot more about what people actually were eating,” based on clear advice for what to eat (or not), what is good for you (or not). It’s “a very different kind of aesthetic than dining, which is obviously intended for just gastronomic pleasure.” Instead, nutrition books tell you how to eat and remain healthy: Something Albala says we might associate with modern dietary writing.

Health guidance in early European printed books came from humoral medicine, a medical system that originated in Ancient Greece and Rome, and relies on the balance of four humors. Albala says, “It’s the whole idea that food can be categorized according to one of four basic combinations of elements, meaning that they’re either sanguine or phlegmatic or choleric or melancholic, and that whatever you eat will change your own body balance of humors.” Humoral culinary guidance is mostly based in flavor: sweet foods are hot and moist and sanguine. Watery foods are phlegmatic. We still use humoral terminology to describe food today: A martini is “dry” despite being liquid, spicy food is “hot” regardless of its physical temperature.

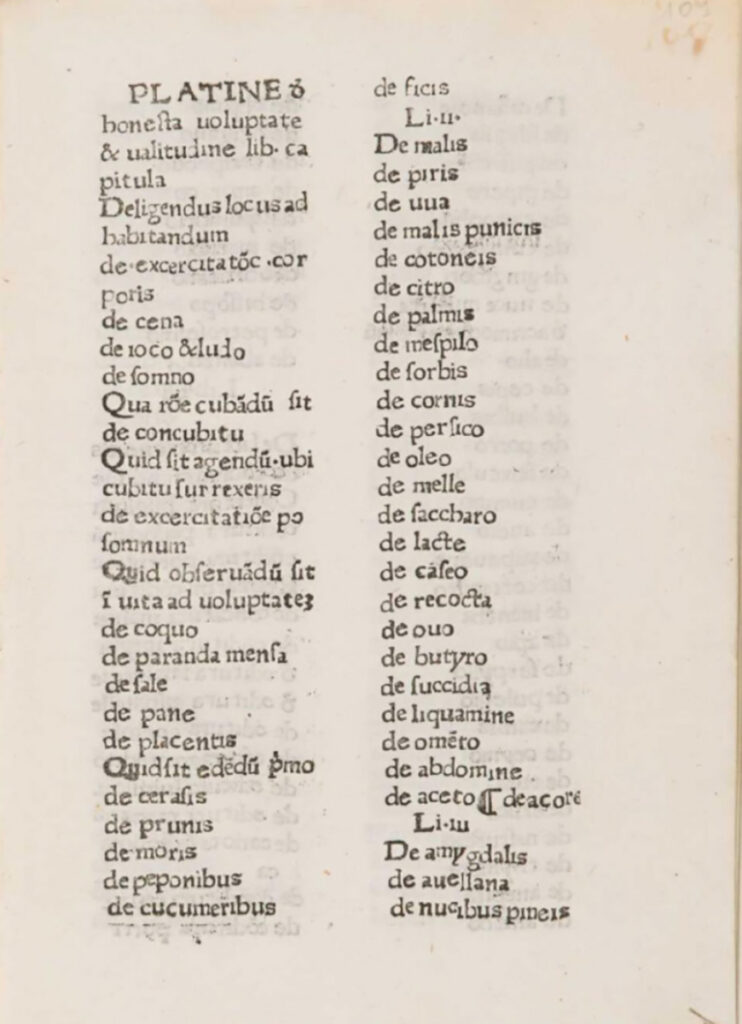

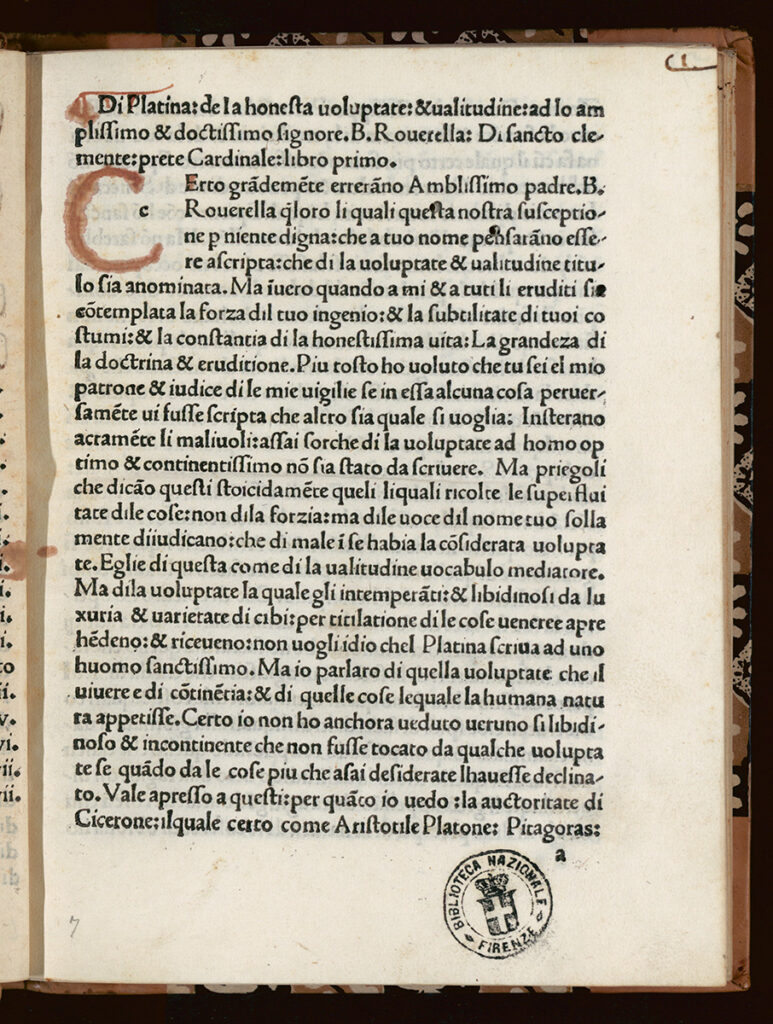

The first known printed cookbook, De honesta voluptate et valetudine was written by the Italian Renaissance writer Platina in the 1470s, but it’s also the very first printed health manual: a clear statement of the convergence of health and diet. Platina, who became librarian of the Papal Library, took the recipes from a manuscript cookbook by Martino of Cuomo, and plugged them into his health manual. The result is a mishmash: Which Albala calls “two separate books that don’t sit very happily together.” The cookbook, as a collection of recipes, does not really take off for about another century or so.

By the 1600s, new models of physiology emerged in Europe, moving towards more mechanical and chemical-based theories. Our dietary advice, then, becomes less about balancing humors and more about fueling the machine.

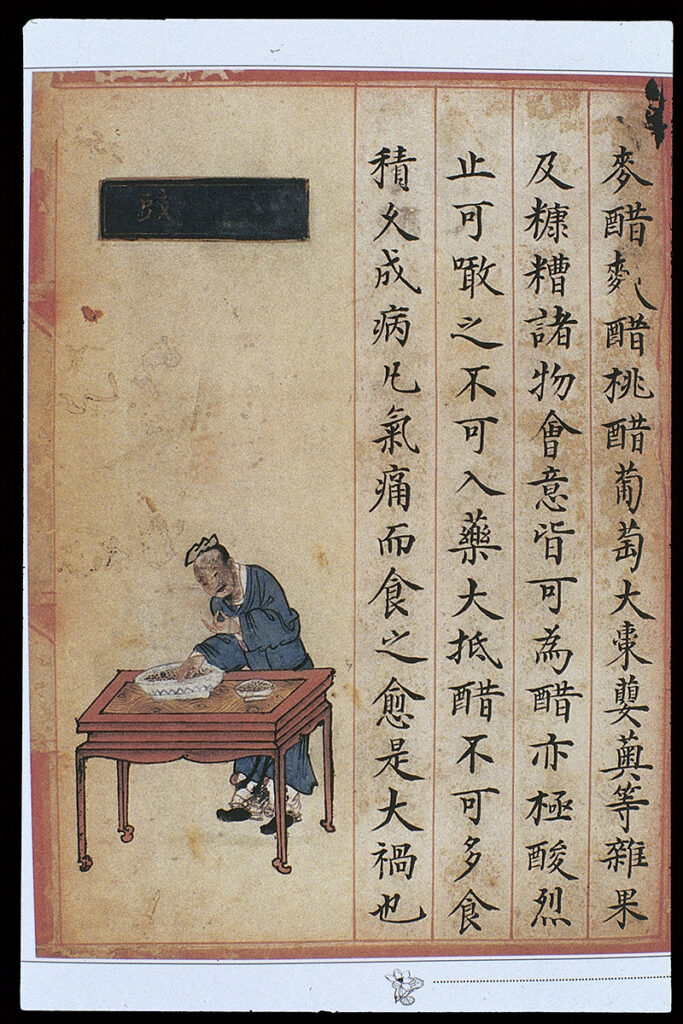

Michelle King, whose research focuses on modern Chinese gender history and food history, notes the same trend in China: Before print, early agricultural, medical, or ritual texts both describe food and in some cases include some clues to how to prepare it: but they are more about preserving existing knowledge than providing hands-on, experiential learning. Every rule has an exception, though: “there’s an agricultural treatise from the sixth century, and it does have recipes in it because the cooking part was part of how this scholar saw all of agriculture.” What was written down was part survival, too: Many of the early Chinese texts about food are all about preservation: Pickles, sauces, alcohol making, drying, and otherwise taking the abundance of one part of the year and stretching it out as long as possible.

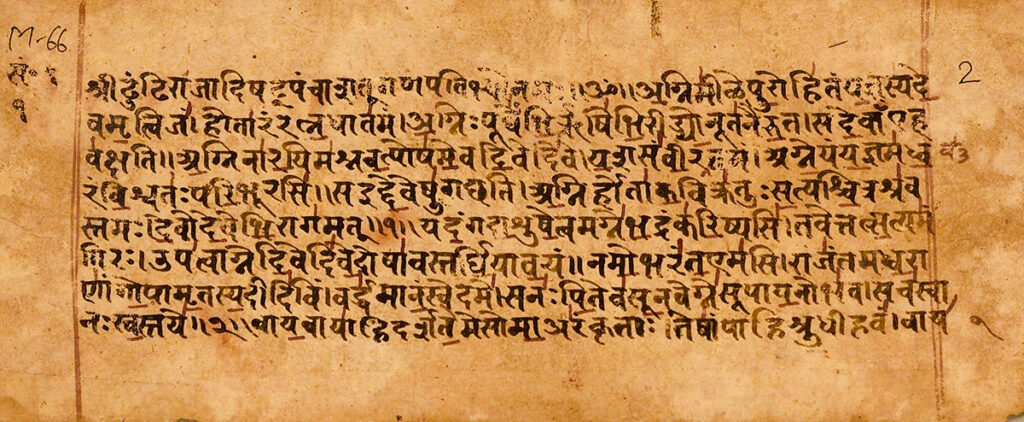

Chef and author Nandita Godbole notes that in India, prior to the printed book, much of our culinary knowledge through history comes from medical and religious texts: The Vedic scriptures, for example, outline eating aligned with the seasons, and how to prepare it to ensure it’s beneficial, which evolved into what we now know as Ayurveda. And, class dictated what was recorded: Which means most of what we know comes from nobility. Local populations were not writing down recipes, but the wealthy rulers (or at least their scribes) documented the recipes of courtly chefs. However, it’s of note that the chefs themselves were not interested in sharing their recipes in a replicable way, because to do so might render the chef replaceable. In the 14th century onwards, and “even into the 19th century when printing started to come into play,” with recipes, “the knowledge was so tied to the chef,” Godbole says.

The British government suppressed Ayurvedic health information in the 19th century, arguing that it was teaching people to self medicate. But with that suppression came a suppression of culinary heritage. Godbole says, “those Ayurvedic texts actually held information about how to cook certain things: simple things like how to make a particular kind of ghee, that was good in the winter months versus in the summer months.” She adds, “it’s all cooking,” even if those texts aren’t what we’d call cookbooks, because their culinary knowledge is buried in a medical or other text. Godbole was shocked to learn about the level of suppression of traditional medical knowledge by the British colonizers.

Rather than understanding the reasons behind it, the cuisine simply became marked as “exotic” and too complicated for the almost certainly wealthy, male reader. “British books [about Indian cuisine] were written a certain way because they were really just promoting Indian cuisine as this exotic, complicated, very, very difficult to procure, understand, cuisine.” The food exists decontextualized and the foodmakers erased: from history, from community, from their origins. Godbole continues: “They were trying to capture Indian cuisine in a manner that would be like the spoils of war…capturing the cuisine as part of control.”

Aspirational Reading

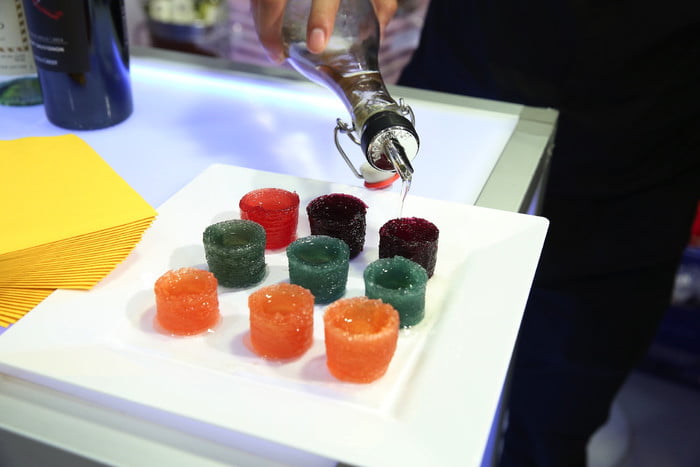

Nutrition books are revelatory in a way cookbooks are not: Nutritional advice is based upon the kinds of things people are eating, and how those intersect with the body. We know, for example, that people in Europe were cutting peaches into small cubes then putting them in their wine before drinking it. Why? because nutrition books warn that the peach cubes in wine are bad for us. “They’re very clearly describing what you shouldn’t do, and that’s good evidence that people were doing it,” Albala says.

The cookbook, on the other hand, is aspirational: We buy cookbooks for what we want to be eating, which may not always align with what we eat (or should eat).

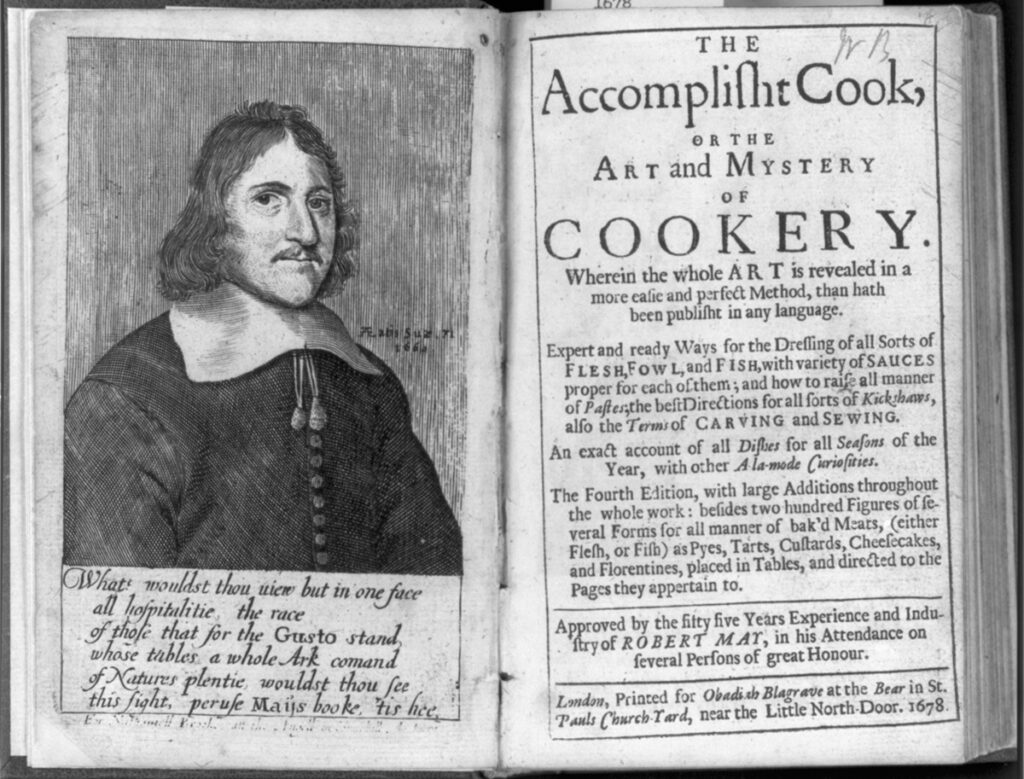

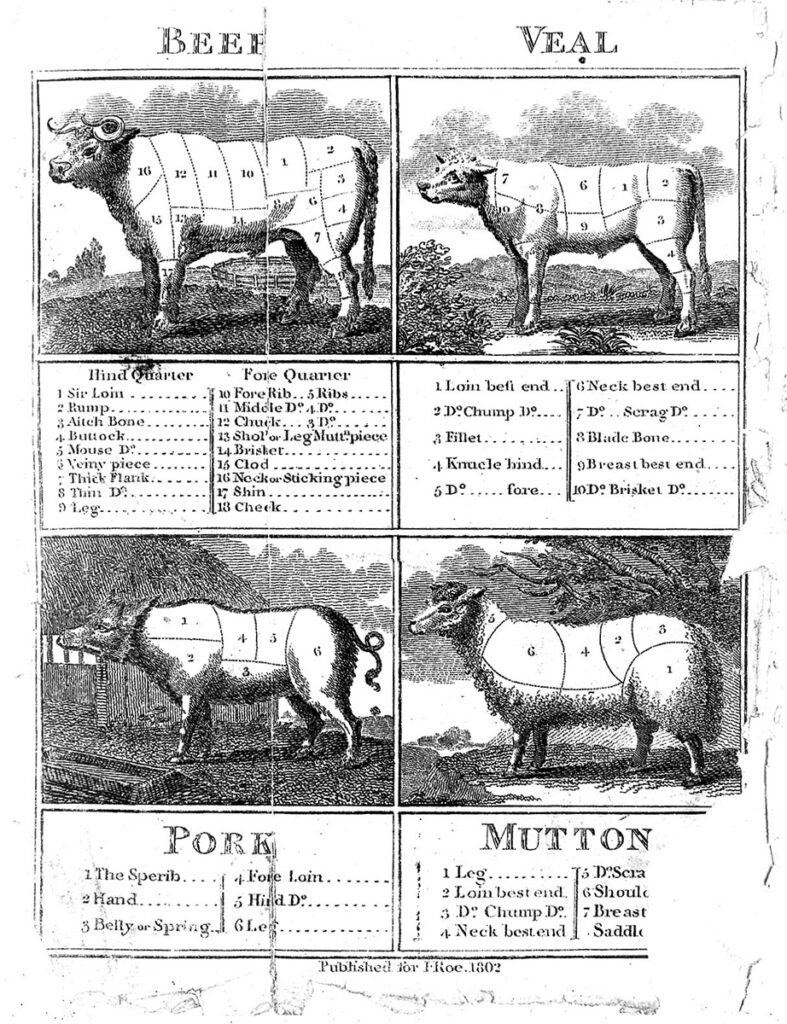

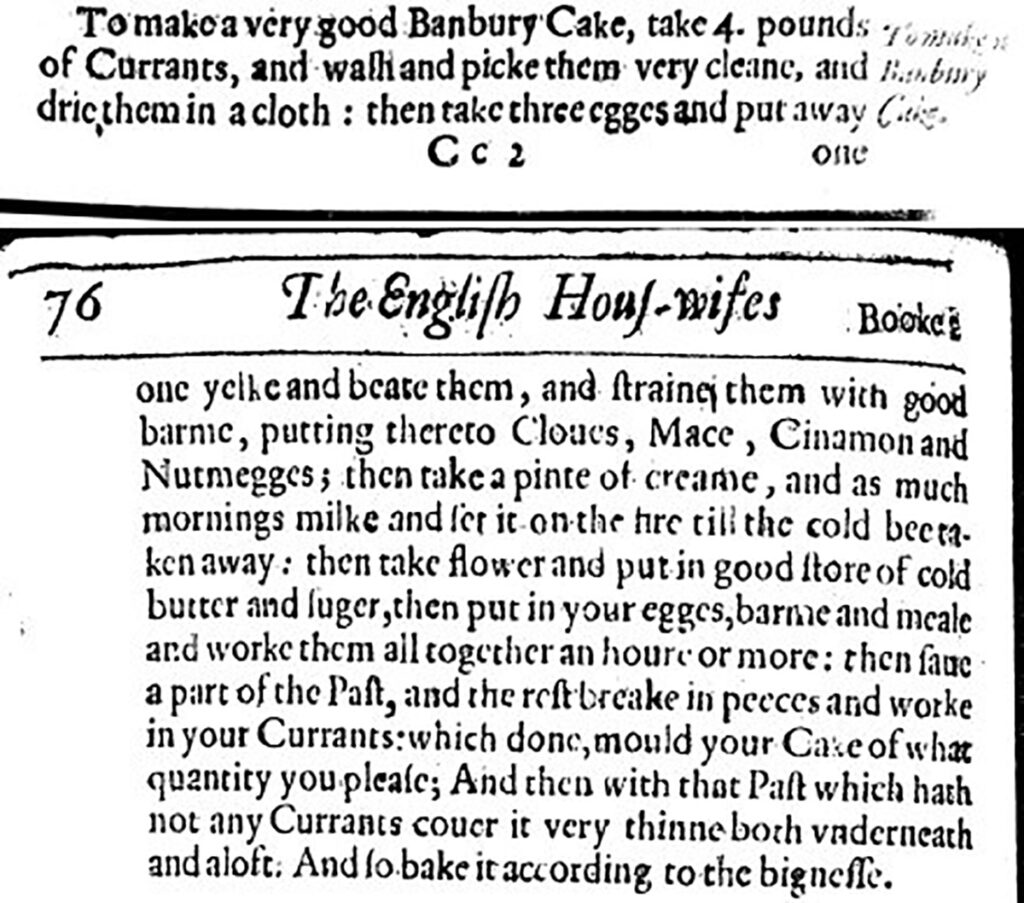

In the 17th century, cookbooks in Europe became more popular, and different ones appealed to different audiences or topics: Robert May’s The Accomplisht Cook (1660) focuses on food preparation for the wealthy, guided by the expertise of a professional chef. Whereas Gervase Markham’s The English Housewife was more of an all-in-one manual for the country gentry: And leans into the foods and household management practices you would see in middling households at that time.

Jennifer Stead notes that in the 1700s more English-language cookery books were written by women, which were incredibly successful in this market, including authors like Elizabeth Raffald The Experienced English Housekeeper (1769) and Hannah Glasse’s The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy, which went into more than 17 editions between 1747 and 1803 (and, just like today, many other folks pirated popular recipes from Glasse’s book).

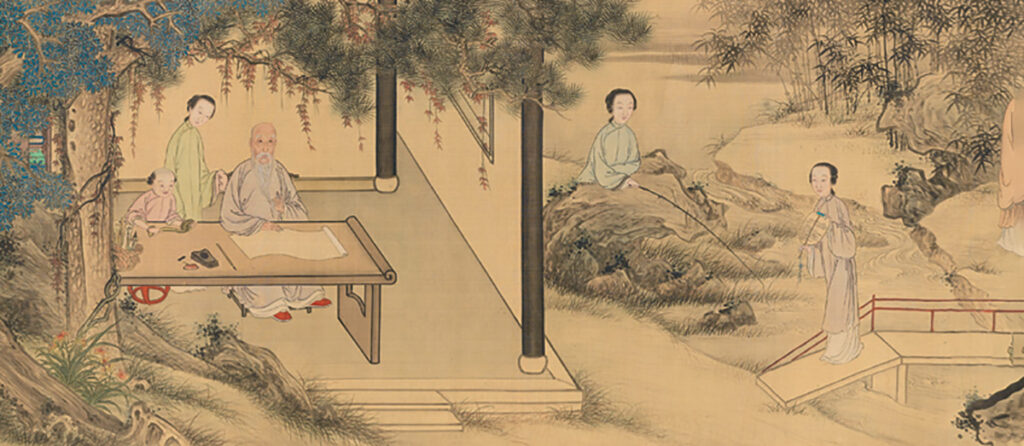

Early Chinese culinary books were, like European ones, primarily written and read by men. Yuan Mei’s 18th century Recipes from the Garden of Contentment, does include recipes but, King notes, it’s mostly about discernment: “What’s the right way to enjoy something?” However, she notes, he wasn’t the one cooking: He employed a chef. Mei’s work is a gentleman writing for other gentlemen, saying what they should ask their cook to do. “That’s why I say it’s not really what we think of as a cookbook,” King says, “the cooks themselves would probably not have been literate.” In books at this time, the focus is on product, not process: “the gentleman’s taste is of paramount importance—more than the skill of the chef himself.”

As we move further into the 19th century, urbanization and industrialization meant the physical movement of people to cities, but also movement between social classes. And this meant new markets for cookbooks. Maybe you already know how to cook but, as McLoone says, “maybe you don’t know how to give a dinner party that’s going to help you get into the upper echelons of Philadelphia society.” The result? “Mobility in all these different directions.” And a book with clear directions to help you wayfind through social echelons could be the difference between a successful journey, or not.

Cookbooks are as much about whose voices are left out as whose are included: And who readers aspire to be often tells us who is valued. Though the production of printed books was faster and cheaper than manuscript books, these were still initially quite expensive, and coupled with low literacy rates, remained inaccessible to most.

This began to change with the Industrial Revolution, as we moved towards cheaper and quicker (but poorer quality) modes of book production: cheap, acidic paper replacing durable rag paper, and perfect bindings or mass-produced sewn bindings replaced hand-sewn.

This made the printed book, once sturdy and made to last generations, into something more ephemeral. But the good news is that this made books much more affordable for readers, and the production of cookbooks alongside other genres skyrocketed.