Shelf Life is a monthly series at MOLD that explores how we eat at different stages of life.

On some occasions eating can be elevated to ritual, but on many days it’s mundane. By very rough estimates, we eat 71,175 meals between the ages of 5-65, and outside of occasions like birthdays and holidays, most of our adult meals get lost in life’s everyday shuffle.

Mundane eating is part of the pattern of growing up; meals fit between obligations such as school and work and compete with tasks such as homework and hobbies, and for many families, organizing them adds to the day’s mile-long to-do list. In the grand scheme of our everyday eats, convenience plays a larger role than most of us openly admit.

Convenience, at its worst, is a dangerous driver for eating decisions. Research from the CDC in 2008 showed that middle-income Americans are more likely to eat processed fast foods than any other population group, and they are more likely to struggle with obesity. “Convenience” is cited as their primary deciding factor at mealtimes, above even food cost.

Recent food trends encourage people to slow down as they eat, to eat together, to eat beautifully at every meal—but these messages can feel out of place for individuals struggling to balance family, professional, and personal obligations. So the question becomes, how do we approach food thoughtfully in the busiest years of our lives? Instead of pushing against convenience eating, how do we responsibly embrace it?

**

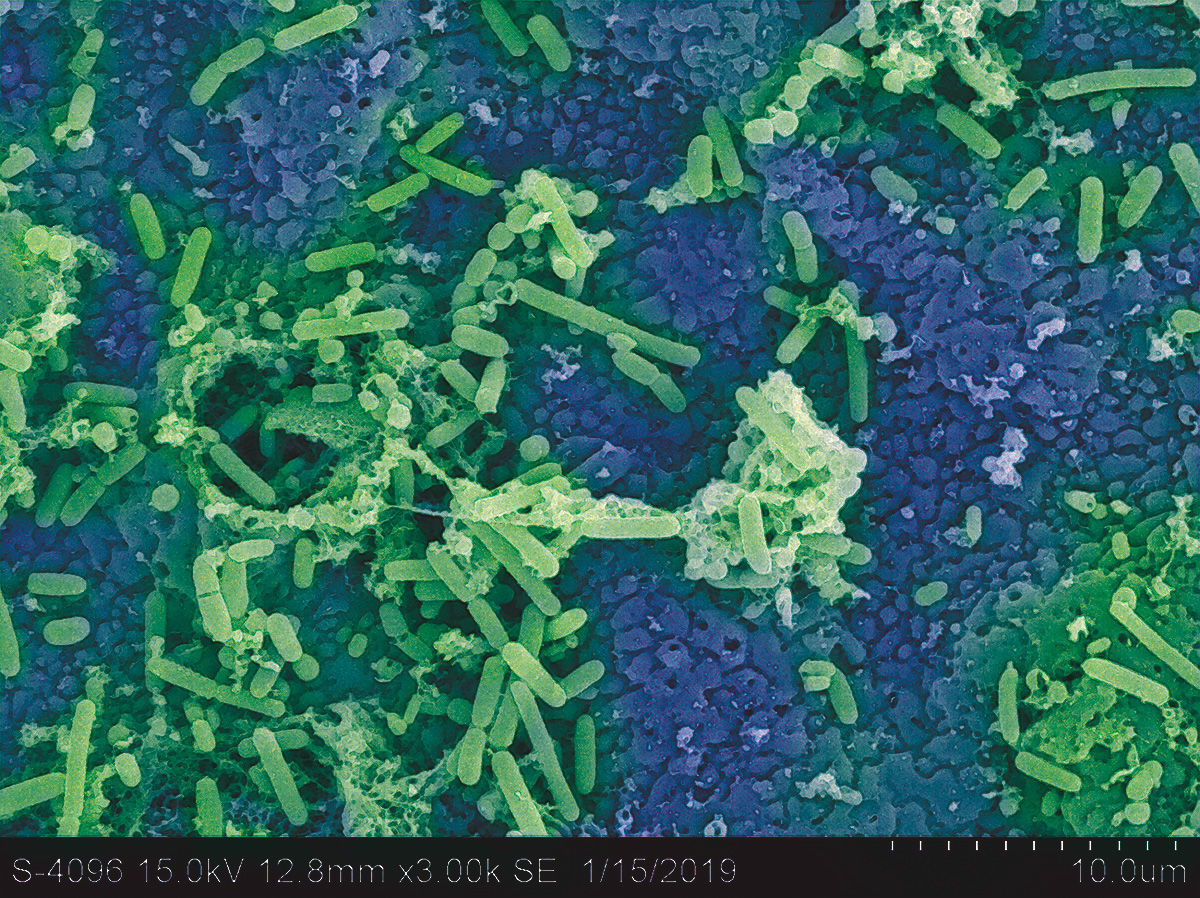

The first, and often most difficult, step in everyday eating is deciding what to eat. According to 2016 research, as many as 80 percent of Americans don’t know what they’re having for dinner by 4 p.m. that day, and 36 percent feel guilty about what they ultimately choose. Some designers strive for a panacea of an answer, creating substances that will encompass all nutritional demands and eliminate the need to decide. We’ve seen this value statement first with meal replacement shakes, and now with products like Soylent, algae-based Nonfood, powdered Huel, and the noodle-inspired Vite Ramen. But not everyone responds to meal replacements in the same way; as countless reviewers note, each person’s unique gut flora will digest these products differently.

Image courtesy of Viome

Image courtesy of Viome

The need for personalized options introduces a new designer into the process: the computer. The largest working class of meal designers today are algorithms, many of which are employed to make convenient decisions for consumers based on personal factors. They range from EatThisMuch, a simple algorithm that rotates daily recipes based on a calorie goal, all the way through to PlateJoy, a total subscription service that personalizes recipes, grocery lists and even grocery delivery based on a 50+ question family survey. And then there’s Viome and its recent acquisition of personalized health platform Habit. Viome+Habit gather data from DNA, microbiome samples (including bacteria, yeast and fungi), lifestyle surveys and health goals to personalize a nutrition plan. Habit has tested meal delivery before, and Viome has indicated that it’s acquisition is part of the long-term business roadmap.

Image courtesy of Shu Ou

Image courtesy of Shu Ou

A near future of hyper-personalized, delivered meals inspired Los Angeles-based food designer and researcher Shu Ou to imagine the “convenient” dinner table of 2025. Her concept depicts a dystopian weekly routine of Precision Meal Bars—individually-customized nutrition bricks flavored for different days of the week. Her concept also includes Nostalgia Snacks, flavored to remind us of foods that are not nutritionally required and have been phased out by food companies of the future.

Yet, as consumer surveys and popular media will tell you, people want to cook real, non-bar food at home—they just simply don’t have the time. Family members (usually women) cooked, on average, two hours a day just a few decades ago; today, half of all dinners need to be prepared in 30 minutes or less. This time constraint limits the scope of made-at-home meals—according to a 2017 NPD report, among the most popular meals prepared at home are cold cereal, toaster pastries, yogurt and tap water. The social pressure to cook fresh at home guilts many individuals from voicing their realistic in-kitchen needs; ultimately, this perpetuates a food culture that promotes home cooking when many individuals simply don’t know where or how to begin.

Photo courtesy of The New Modern

Photo courtesy of The New Modern

This is where kitchen technology stands to provide a large-scale service. While the fully robotic kitchen feels sterile and financially unattainable for most, new designs are helping people fit home cooking into their schedules, one dish at a time. There are high-priced, full-cooking devices such as Suvie and Tovala, which are aimed at high-income millennials such as bachelor computer engineers (the popular promo video stereotype). But there is also room to reimagine home cooking without product barriers. A 2017 project by Israeli studio The New Modern stands out for its low cost, low price, no onboarding approach: their Sous La Vie waterproof bags—which cook vegetables, meats, and fish using the sous vide method—are thrown right into the family washing machine. It’s an elegant approach that works with technology already in the home, instead of introducing new routines at a high cost.

Yet, there will always be days where we simply can’t make it to the kitchen. Meetings that stretch into evenings, children’s soccer matches and flute lessons, and forgotten packed lunches inevitably send us out for prepared food. The fast casual, quick service food market now generates $42.2 billion in sales annually, growing faster than any other restaurant sector, with increasingly healthy offerings.

However, fast casual isn’t an option for all; the average personal check at a fast casual restaurant is $13, while the average home cooked meal comes in at around $4. Those four dollars don’t account for cooking, service and utensils, as restaurant meals do, but the $13 bill is out of reach for many working class families who need quick healthy food options the most. While there’s an entire restaurant category focused on convenient, healthy meals, but for a large number of diners, they’re cost-prohibitive.

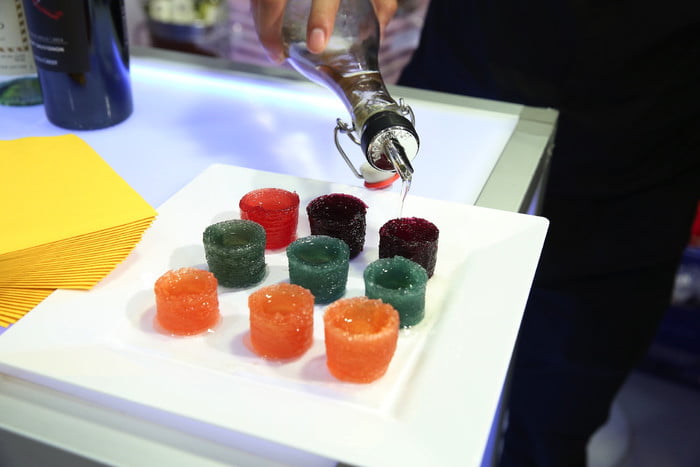

Photo courtesy of Spyce

Photo courtesy of Spyce

Researchers at MIT used economic challenge as inspiration for a concept restaurant named Spyce, opened in Boston in 2018. Designed by graduate students at MIT and chef Daniel Boulud, Spyce staffs a fully robotic back of house, which keeps costs low enough to price meals under $10. “Our purpose is to increase access to wholesome and delicious food for people at all income levels,” says Grace Uvezian, Spyce’s head of marketing and public relations. “When our founders were undergraduates at MIT, they couldn’t afford to spend $10 to $12 on one meal and knew they weren’t alone. Too many people were being priced out of quality. Spyce is at the intersection of hospitality and technology; by combining appropriately sourced ingredients with our robotic kitchen, we’re able to provide meals at $7.50.”

Spyce’s prep kitchen is orchestral. After a customer places an order on a touch screen, a robotic “runner” identifies ingredients in the order and parses them out in a bowl. The portions are then mixed and cooked in 450-degree induction drums and poured into bowls. Human associates plate the final dish and add extras such as sauces. The engineered efficiency of Spyce reduces overhead costs, as well as resource use; the restaurant’s self-cleaning drums use 80 percent less water than typical food service dishwashers.

**

When asked about the movement towards convenient eating, Soylent creator Rob Reinhart says, “We’ll see a separation between our meals for utility and function, and our meals for experience and socialization.” Today’s work and home schedules present the very real need to healthy, accessible and worry-free meals. But while there are positives to confronting the realities of convenient eating, there are implications for making food worry-free. If we’re not the ones deciding which foods and preparation methods constitute healthy, indulgent and accessible for us, we open the door for others to do it—brands, healthcare networks and even governments. Especially in busy times, food is something we may not always want to think about. But if we don’t, who ultimately does?