20,000 eggs, 2,224 pounds of rice, another 2,000 pounds of flour, almost 400 pounds of coffee beans, over 400 gallons of milk (and milk alternatives), whole pigs and even frog legs all packed into a mix of walk-in freezers and dry storage. Steve Pattison, the camp boss and head of the kitchen, lists off the stats of the ingredient inventory with a lighthearted humor. He’s been working and cooking on the water for his entire career, with a good decade under the surface in the cramped quarters of submarines. “It all comes down to proper planning, we can’t afford to waste food out here,” he says in a thick English accent. “You can manage a menu, adapt to people’s preferences, but what you can’t do is be wasteful, so it comes down to not packing anything unnecessary.”

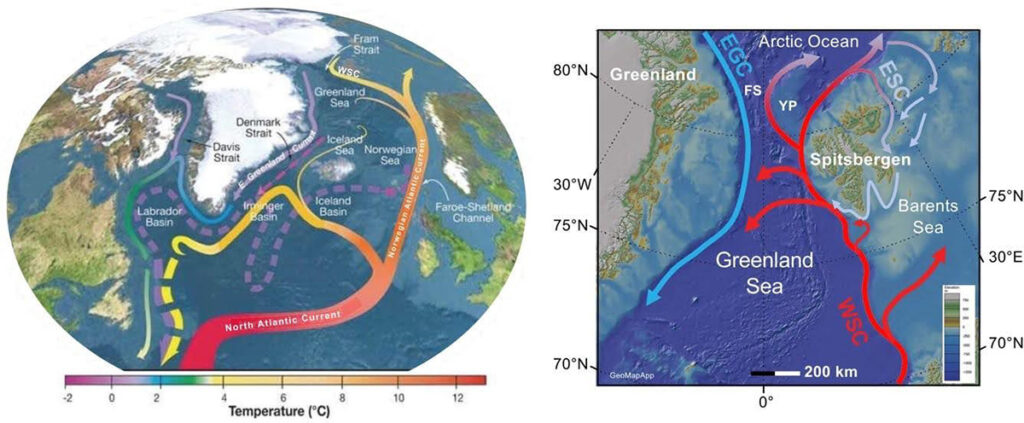

Sitting between Greenland and Svalbard is a deep-water passage that connects the Arctic Ocean with the North Atlantic below it. Defined by two large currents—a warm northward current flowing up along the coast of Spitsbergen and a cool southward current flowing down the coast of Greenland—the passage acts as a gate into the Arctic. The exchange of these currents has historically been a strong forcing mechanism for climate change both regionally and globally because of the temperature, salt and moisture that is moved in and out of the Arctic through them. For what appears to be its final expedition for the program that operated the JOIDES Resolution, a former commercial oil exploration vessel turned NSF research vessel, aims to collect samples from sediment drifts that have accumulated for millions of years along the sea floor. The sampled sediments act like a book, recording major climate events of the past and offering a better understanding of the exchanges of these large water masses. Both acquiring and reading the pages isn’t easy, however. This process requires specialized drilling equipment and a mix of specialized scientific working groups collaborating as a team to make sense of the “what and when” of the data.

A major focus for the scientists onboard is the rapid decay of an ice sheet that extended over Svalbard and the Barents Sea roughly 21,000 years ago. By understanding when and how the heat transferred by the warm north current triggered the rapid decay of the former Svalbard- Barents Ice Sheets, researchers can better predict the future behavior of the vulnerable West Antarctic Ice Sheet under the present global warming.

The sampling sites are remote, which makes replenishing supplies by land, boat, or helicopter out of the question. Onboard is a mix of scientists, roughnecks, engineers, sailors and specialized support staff ready to work 12-hour overlapping shifts, 7 days a week for two months. This amounts to the need of storing enough food to feed 120 people four meals a day (sometimes serving breakfast, lunch and dinner simultaneously) non-stop for two months. Added to this is the challenge of the diverse cultural food preferences of everyone onboard, a mix of food allergies, along with the need to keep everyone nutritionally well balanced, and happy enough to work around the clock.

“There are only two places on the ship that can end an expedition early; The bridge coming from the captain, or the kitchen coming from the cooking staff” Fabricio Ferreira, a marine technician, explains while sitting in the ship’s galley. Laughing a bit at his remark before reinserting with a more serious tone “it is true, food is what keeps people going at sea, scientists will just stop working.” He says this as he was getting up, gesturing that he had to get back to work. In brown Carhartt overalls spattered in gray mud, and with a half-filled coffee cup, he made his way back up to the labs.

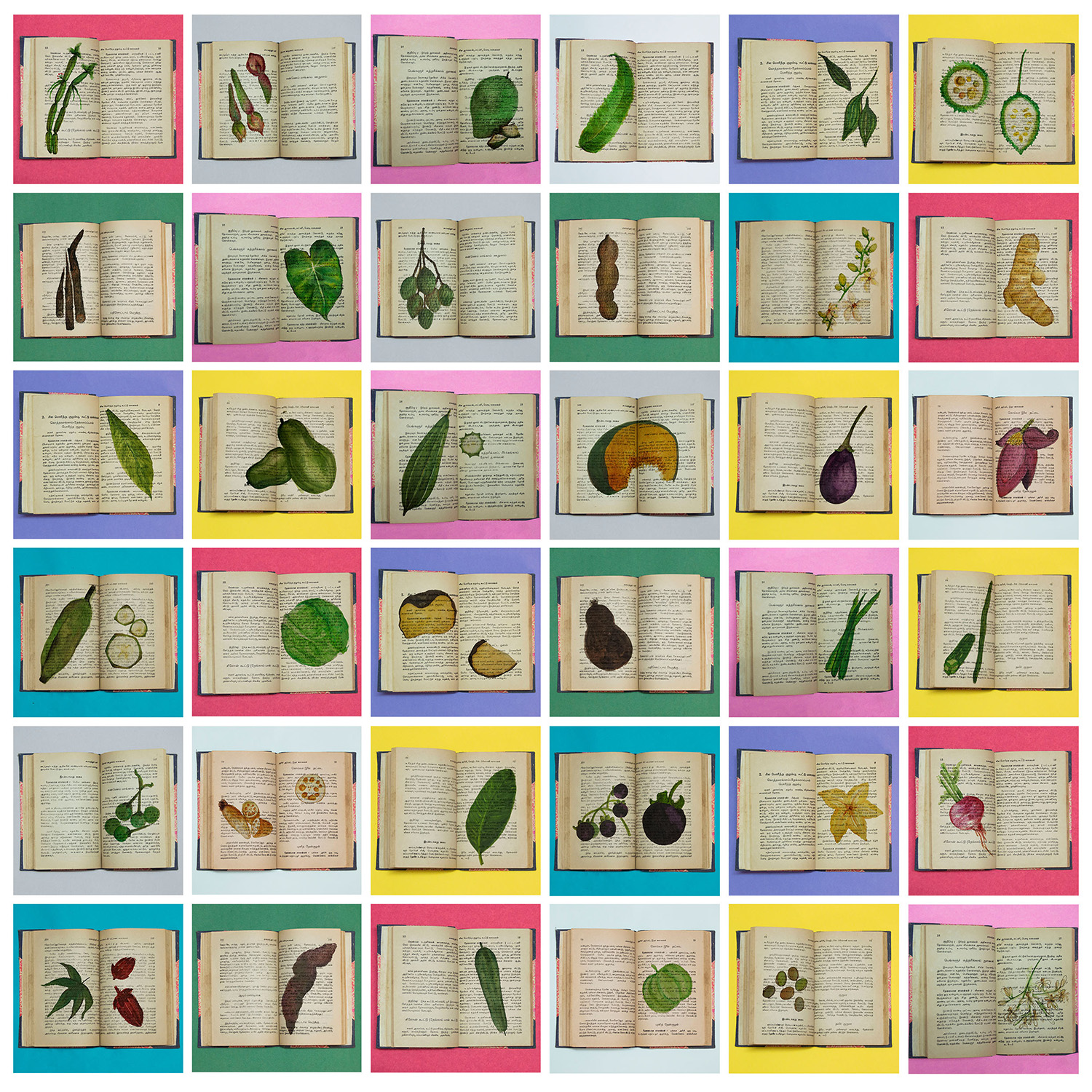

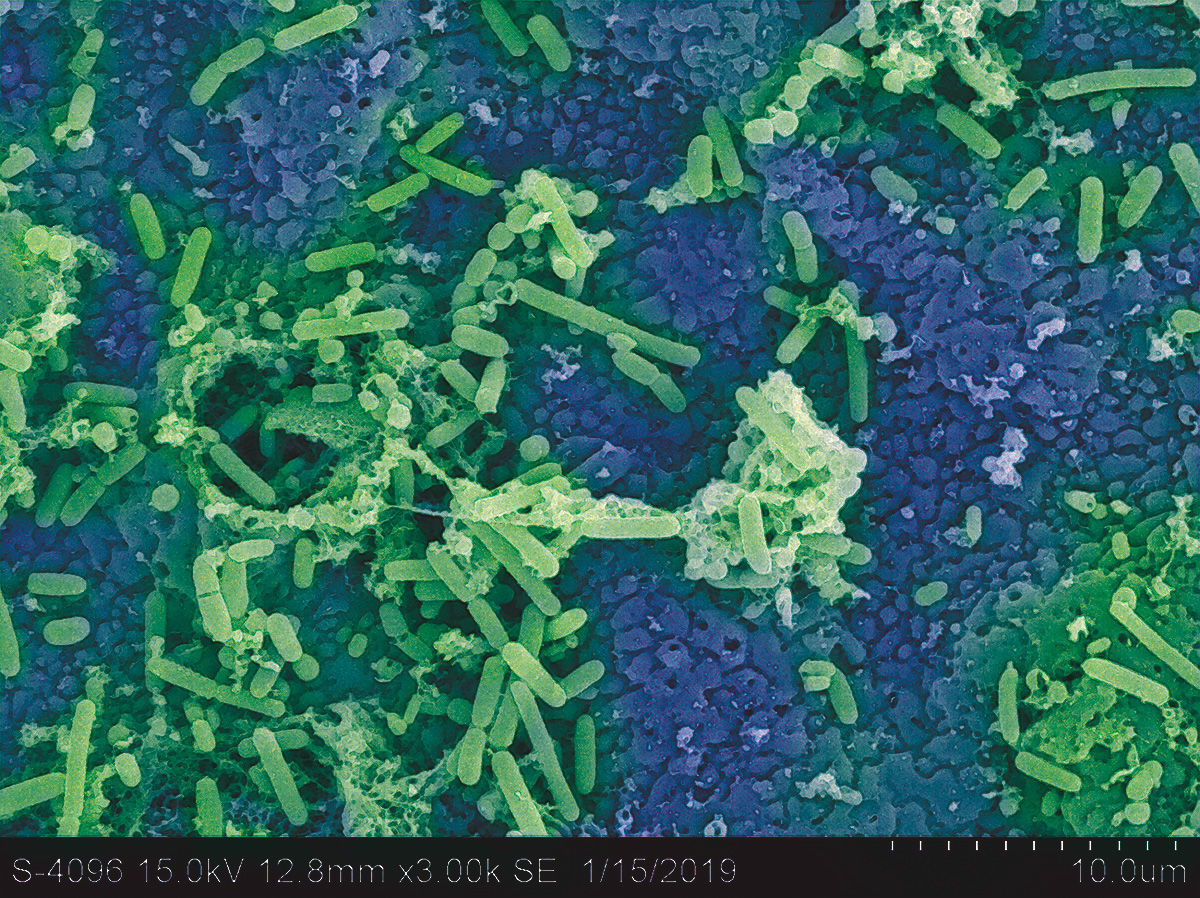

Behind the galley sits a large stainless steel lined cooking space, fitted with all the toys a typical industrial restaurant kitchen on land would have. Jun Olegario, the chief cook onboard, and Joven Sumbo, the assistant cook, chop vegetables for the 17:00 – 19:00 meal. “The biggest challenge is ingredients,” explains Jun. “No, it’s keeping everyone happy with the ingredients we have,” adds Joven. The two men let out a laugh as they go back to work. In front of them are two bowls of carrots and potatoes.These heartier veggies will become more and more foundational towards the end of the expedition. Building an adaptable menu for so many people when the variety of ingredients gradually diminish is a challenge. Even with advanced freezers, round-the-clock monitoring, and exceptional hygiene standards, certain foods will spoil before the end of the two months. “You can fill the boat with bananas or you can bring ten, it isn’t going to make a difference, they will all spoil the same,” Steve says from the back of the kitchen.

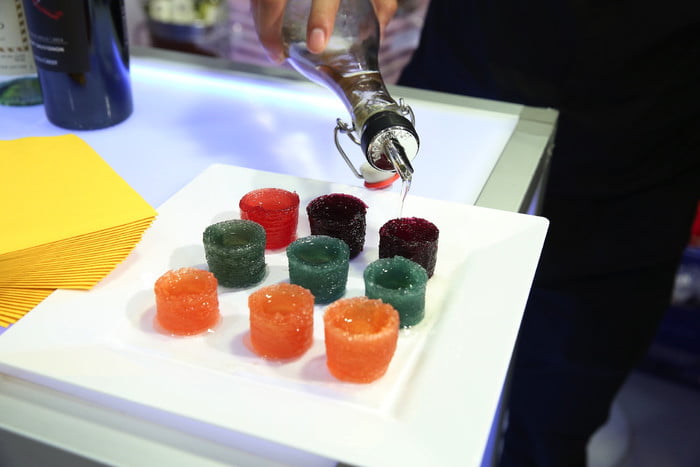

The three men are preparing for an upcoming holiday meal; Fourth of July will bring a mix of BBQ, apple pie and burgers. Steve is preparing the patties, freshly ground rump steak with a mix of onions, garlic, salt, and a dash of Worcestershire sauce, while Jun and Joven move onto preparing the meal for the evening ahead. The holiday meal is less about celebrating American independence, and more a chance for the kitchen to show off an extra flare of culinary skill. Added is the fact that a strong majority of the boat’s inhabitants (both science party and extended support staff) are not American. Every holiday comes with a themed meal, and in this case, the freshly baked apple pie is better than most places back on land. A typical meal is served cafeteria style with four options to choose from: normally two main course options, a vegetarian option, and a traditional Filipino dish. With the Filipinos filling an estimated 1.65 million seafarering jobs worldwide, the fourth dish is a given to provide for the needs of the majority of the working staff on the vessel (both Jun & Joven included). Omelets and waffles are prepared upon request to account for those eating breakfast, along with salads, soups and baked goods prepared daily.

Cooking and feeding large groups of people while at sea is far from a new problem. Egyptians carried dhourra cakes, Roman’s had buccellum, and the British Navy had hardtack. All a combination of baked grain with the purpose of three things; minimal space, maximum shelf life and nutritional efficiency. They, too, couldn’t carry anything unnecessary. Despite the changes in technology since the Egyptian or Roman Empire, the goal of small, non-perishable, nutritionally dense food hasn’t changed much for life at sea. The tight constraints provided by circumstance reveal deeper questions about what food is and why it is important.

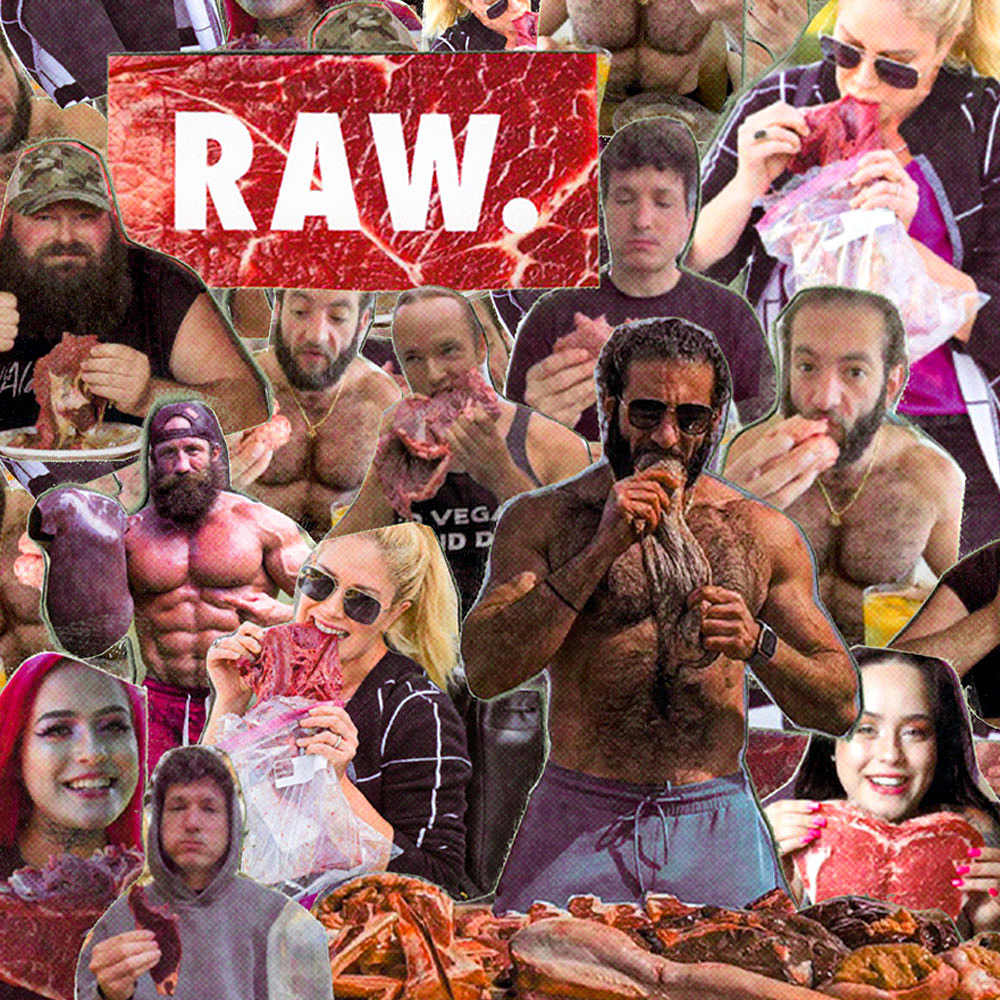

Put simply, food is our only supply of energy and without a steady supply of it we will die. Contemporary abundance has let much (but not nearly enough) of the world forget this fact, but this reality informs much of the planning, storing, preparing and serving of food on an expedition such as this. In the face of this fact about food and survival, both taste and preference can’t be ignored either. Anything that doesn’t get eaten takes away from the endurance of the expedition, meaning anything that ends up in the trash is wasted both in food and the storage space that could have occupied something else. So, food may be a store of energy, but it isn’t just a store of energy. As Fabricio pointed out earlier, the kitchen is one of the two places that can bring things to an early end. Food keeps people happy, creates an opportunity for connection, and historically has built bridges across both language and culture. So even in the Arctic, the joy of food is a factor to be considered, meeting taste and preference is what keeps food out of the bin. Interestingly, to solve for all the variables of variety, spoilage, and joy, the solution is to invest in raw ingredients, rather than heavily processed or pre-prepared food. Economic cost, space occupied, nutritional availability, versatility and even carbon footprint (of shipping rather than purchasing regionally) make investing in quality ingredients an obvious choice when factored with the availability of the skilled labor to make use of those ingredients.

Both Jun and Joven have been working on the vessel for over a decade, working up from entry positions into the roles that they each hold. With so much time spent together at sea, many of the crew see their colleagues as a sort of second family. Jun attended Steve’s wedding, with the former head steward doing the same to serve as Steve’s best man. Despite the months at sea, long hours and ingredient constraints, I am told the only way a new position opens onboard is either from a retirement or death. Compared to the oil and gas industry, which many of the support staff come from, the pace and environment of the research vessel is a positive change. It also goes to show that people don’t want to leave a good situation. Keeping people alive and happy in the Arctic comes down to investing in quality ingredients and the people that make the most of them.

Perhaps this insight is something to be carried home.

Back in the kitchen, shifts are about to crossover with the night crew taking over. Just after 12am the galley is clearing out and about to be put back together for the next meal in just four hours. Jose Marco Masiclat, the kitchen’s baker, begins preparing bread and desserts for the following day. The metal roll gate is getting closed at the cafeteria style serving window. Another shift, another day, another barrage of hungry people, far from home, ready to sit down and eat a freshly made hot meal. Between the months of April and August the sun never sets in the Arctic Circle, it only runs laps around the sky, leaving the night shift to begin their day cooking under a midnight sun.

Tim Lyons, Chris Lyons and Khyber Jones join Expedition 403 to document the final IODP expedition for the upcoming feature-length documentary: The Time Travelers. For more information visit the expedition page on the International Ocean Discovery Program website.

Stay up-to-date with expedition news on the JOIDES Resolution X(formerly Twitter), Facebook, and Instagram accounts.