Dynamic, connected, and balanced are the three words that best describe Panetteria Rio Dal 1929, a small bakery with a big mission that sits on the riverside in Mantova, Lombardy. For the owners Michele Sganzerla and Elisabetta Szabò, baking is a political act and breadmaking a way of communicating, connecting and expressing feeling. This panetteria is an activist bakery, where change can be savored with every bite through a counterculture of slow-processes in a fast-paced world. Every day, Michele and Elisabetta work to expand the definition of what a bakery can be, a slow laboratory for research and exploration, where one might find dandelions drying and ginger beer brewing.

As people around the world set their Christmas tables by sharing in the Italian tradition of including Panettone, a cupola shaped sweet bread typically dotted with candied fruits, we took the opportunity to check-in with Panetteria Rio Dal 1929. Their version is both familiar and unlike other versions—beginning with the pasta madre (or the sourdough starter), this year’s special edition reflects the unique approach that has set the bakery apart: engaging with local artisanal businesses, the season’s harvest of pumpkin, honey and semi-wilted grapes give Rio Dal’s panettone its character. In the below conversation we reflect on the importance of being in a reciprocal relationship with nature, having clear values, building community, merging tradition with innovation, and how we can shape new food narratives for the future.

Lara Bongard:

Congratulations on winning the Premio Tre Pani award.1 To start, can you tell me about the history of the bakery?

- 1. The Italian food media company, Gambero Rosso, announced its annual award winners in June. The “Premio Tre Pani” is awarded to the 15 best bakeries in Italy, the highest recognition for bakers in the country.

Michele Sganzerla and Elisabetta Szabò:

We took over the bakery in 2018 from an older couple who had owned it since 1929. The house has an incredible history, we have old documents which tell us that people have been making bread in this building since the 1800s. The bakery sits on the waterside of the river Rio and in the old days a watermill was attached to the house and was used for grinding flour. We have a project aiming to rebuild the watermill so we are able to grind the flour ourselves.

LB:

What is agriculture like in the region of Mantova?

MS and ES:

Almost all of the farms in this region are farming intensively—mass producing monocultures using chemicals and fertilizers. Our mission is to change this. With our project we want to ignite a new movement. Usually when you buy flour that’s been grown intensively, you pay around 25 cents a kilo, while we pay five times more. We want to bring about change by making people more conscious about the actual price for ethically grown flour.

We always select our producers personally. This way, we are ensured that they share our values of protecting the land and farming ethically. Human values and trust are essential—we know how the farmers work and they know how we work. The whole cycle is connected from seed to table, a short chain from the farmer who plants the seed to the consumer who eats the bread.

LB:

How do you sustain your values around regenerative agriculture and ethical relationships between farmer, artisan and customer?

MS and ES:

Our purpose is leading us and we surround ourselves with people who share our values. Although this path is not that financially profitable, we believe in what we do and that the product deserves the right price. We are building community in the region but also in the whole of Italy. We are part of a project called Panificatori Agricoli Urbani, a collective of about a hundred bakers all over Italy who share the same beliefs.

LB:

In 2020, Panificatori Agricoli Urbani created a manifesto. What is the importance of clarifying its collective values?

MS and ES:

The manifesto gives hope for a real change both in the culture – where the notion of bread as nourishment is missing – and champions a shift in perspective about agriculture and those who process the raw material. The most important thing is to be in contact with the people you work with, this way you can actually see the change you’re making, while visiting the farms and continuing to educate ourselves — it is a communal process of building a better future.

We are trying to create a counterculture of slow-processes in a fast-paced world through reconnecting with our senses, taking things step by step, while being conscious and present in the process.

Michele Sganzerla and Elisabetta Szabò, co-owners of Panetteria Del Rio 1929

LB:

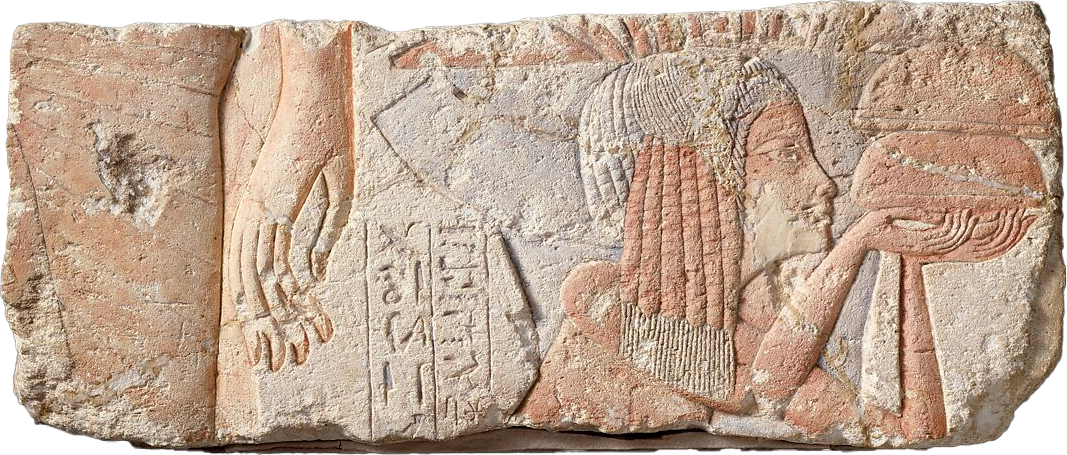

Bread is one of the most interculturally shared foods and bread making is one of the most ancient of human practices — bread connects us as humanity. As bakers, you are part of this long line of artisans. I believe it’s important to recognize the people, history and traditions that are part of a craft, to know what you are building upon. What role does culture, tradition and heritage play in your practice as bakers?

MS and ES:

It’s a way to rediscover the ancient traditions of bread making. There is this thought that traditional is old fashioned, like what your grandparents did, so we have to rediscover what traditions mean to us. By looking at the past and learning from these traditions, but then translating them for the future with innovation, we can shape new food narratives that will fit in this time.

LB:

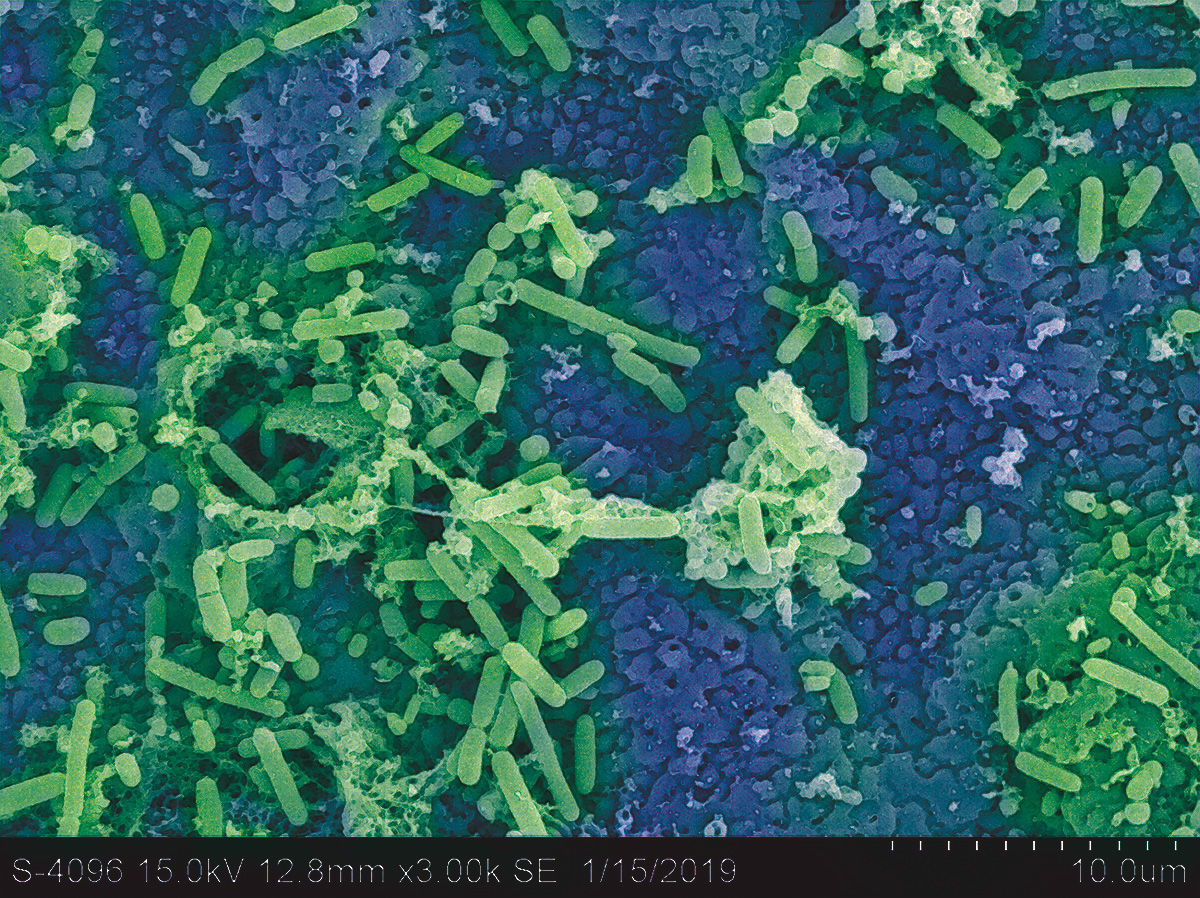

You wrote on your Instagram page about the slow art of pasta madre and bread making. What makes the process of sourdough so special?

- 2. “The process of sourdough takes more days. Presence, attention and love lead to the result… an emotion for those who produces them, but also for those who eat them.” – @panetteria_rio

MS and ES:

We take our time to make bread. Sourdough is a very slow and time-consuming practice, it takes 1-2 days in order to control the process, while making conventional bread with dried yeast takes just a few hours. The first step is to manage the sourdough for 24 hours, then we knead the bread, let it rest for another 24 hours and then we bake it. By going back to the natural way of making bread it takes a long time but this is as it should be. With conventional bread everything has to be as fast and economically as convenient as possible — it’s not about health or sustainability. Mass production has been ruining culture and traditions, people are forgetting about their heritages, and this goes so much further than just bread. We are trying to create a counterculture of slow-processes in a fast-paced world through reconnecting with our senses, taking things step by step, while being conscious and present in the process.

LB:

How does the work environment, the relationship between all of you, influence the product you make?

MS and ES:

We adapt this kind of slow thinking to everything. We make bread for two days, in order to have it on the third day. But we live this way too, we take our time and consider ourselves — because the human that’s behind the bread is the heart of the bakery. We work here as it should be in every company I think; the way you create the work environment together is part of the bread, part of the product we are selling in the end. If we had to make bread in a fast environment, the bread would be completely different because you taste not caring, you taste where people’s values lay, you taste disconnection. When you are valued in a work environment, you want to be there, and it shows through the product you are making. Everything is connected between the bread we make and how we feel inside. If we are tired or stressed, it reflects and it shows in the bread.

LB:

You say “Bread is the horizon and the pretext to explore things.” In what way can you describe the bakery as a laboratory for research?

MS and ES:

Dynamic is the perfect word to describe the process of sourdough, it’s never the same. All fermentation processes are super dynamic, which also represents us as the bakery too. We are always opening our minds and exploring new techniques, always changing and experimenting, always trying to do things better and discovering new horizons. But we didn’t start like this! We started slowly, with just the sourdough, it has been a slow transition in pushing the boundaries of our mission.

LB:

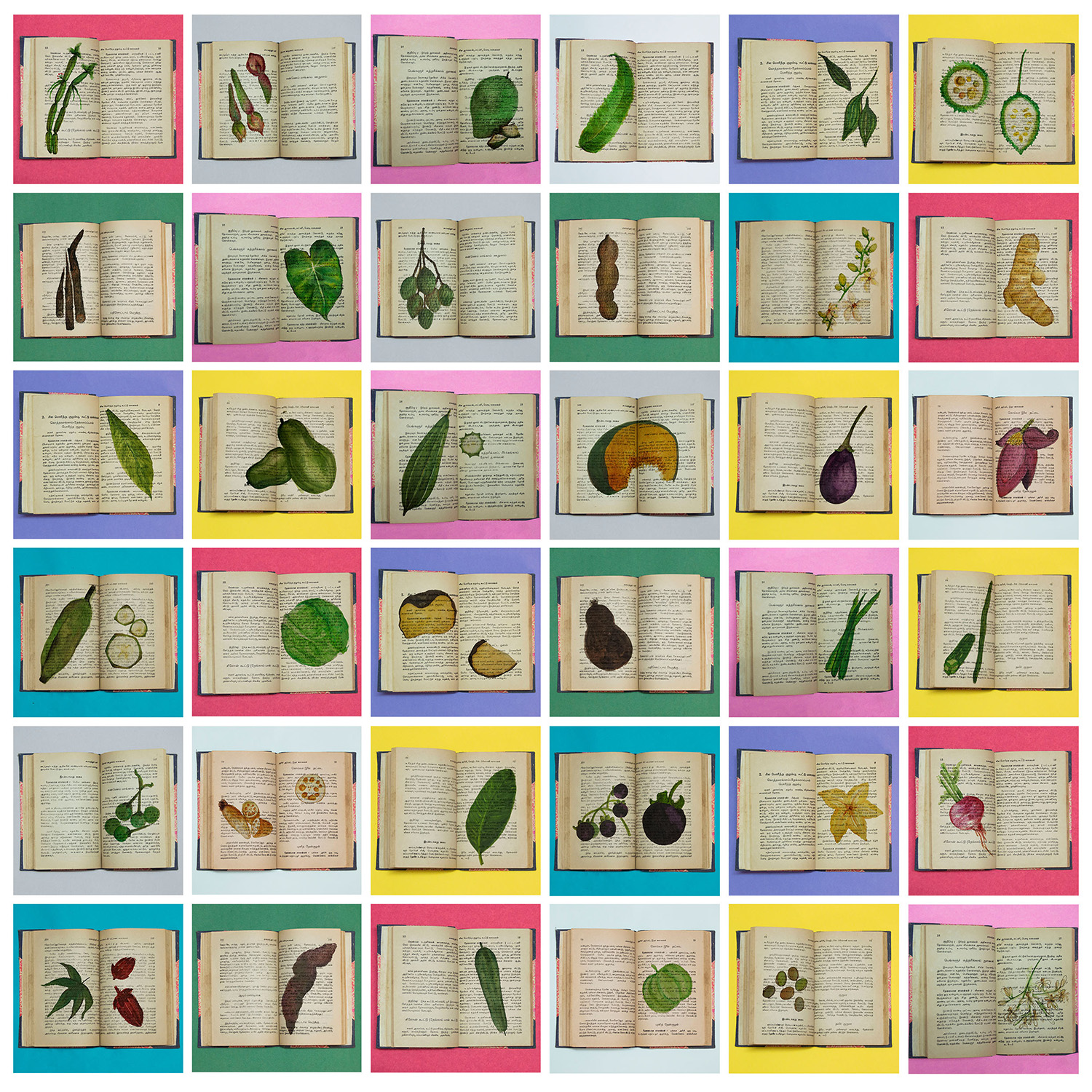

You use a lot of unusual ingredients in the bakery like corn, dandelions, hibiscus flower and elderflower. You call yourself a “garden bakery,” expanding the definition of what a bakery can be.

MS and ES:

Experimentation and expansion are the aims of our project. We look at all the biodiversity that’s around us and bring it into the bakery. Our job as artisans becomes an art form when there is a stable base of knowledge, from there you can expand into limitless ways. We can decide what we put into the bread, the ideas we have become reality and there’s complete freedom in that. As artisans we are a counterculture from the industrial processes of always doing the same thing, this is also why we choose to create a different bread every day. By never doing the same each day, our job will never get boring! The process is dynamic, we experiment with different kinds of ingredients that the farm offers in that particular time or season.

MS and ES:

The ancient grains are very different from the conventional ones. First of all, our farmers don’t use any chemicals or fertilisers while working with these grains, so it’s the opposite of what you would say is conventional.

The downside of conventional grains is that it’s been made in the laboratory. These grains are very short and need a lot of fertilizers, chemicals and water to grow. The chemicals kill the weeds around it, and deplete the soil; the organisms that live in the soil get destroyed which also harms the nutritional values and taste. It’s also not fertile, it’s an annual crop so it can’t regrow. The farmer has to buy the seeds again and plant new seeds with every growing cycle. It’s a monopoly, with the farmer dependent on the seed-bank.

On the other hand, the ancient grains are very tall and strong so they don’t need fertilisers nor chemicals, because the grass and weeds don’t grow taller than the crop. The only thing is, that these grains grow less intensively; so with the same quantity of land, you will have less. The grain is better quality and by using ancient grains you restore the balance back in the soil, it’s a biodiverse way of farming by not overusing the soil.

We buy the ancient grains for a higher price than you would with conventional ones. It’s a sustainable investment because at the end of the growing cycle when you harvest, you can re-use the same seeds to replant.

LB:

It also feels quite metaphorical, symbolizing people and how we polarize each other and our surroundings…

MS and ES:

It reflects it. The people that usually are interested in this kind of agriculture are concerned about nature, they see themselves as part of their surroundings instead of separate.

The most natural way of farming to keep the biodiversity in balance is a method we call miscuglio evolutivo.4 With this method you plant like 2000 different types of grains in the same area and every year, depending on the different atmospherical conditions, there will be seeds that grow and seeds that won’t. The seeds that grow are the ones more adaptable to the conditions and will prosper — this way nature selects itself, without man interfering. Every year it’s going to be different, depending on the conditions of the land. Apart from being the most natural way of farming, this method also gives more certainty for a good harvest. So if a disease is going to spread; some plants obviously are going to die, but the ones that are stronger will survive. It’s the perfect way to maintain biodiversity; it’s more in balance, without humans controlling everything. Instead, the land has authority over itself.

- 4. https://www.vice.com/it/article/wj9ygx/miscuglio-evolutivo-cos-e

LB:

We are currently living in intense times — living through a pandemic, the climate crisis and the breaking of structures of social inequity. It feels like time of transformation. It seems like there’s been a shift in the mentality of people; that the ways in which we were living — the fast pace, the inequity, the depletion — was not normal. What is your vision for the future?

MS and ES:

During the pandemic people had more time to think. Yes there is a change, but often people don’t have the knowledge about ‘why’ they are doing things a certain way. They think they are doing something good — like buying organic in a supermarket, but they often don’t know where their food comes from. As a consequence of this kind of ‘changing of minds’ that’s been going on, a lot of greenwashing is also happening: that’s the dark side of it and this will only increase. It’s a trend, it’s fashion, which creates a lot of mis-information.

We’re just normal people, working with a mission to try to create changes in our own ways. We talk to the people who come here, we explain to them why we do things a certain way. By reaching a person, and then the next person; by informing them and expanding their minds, we hope to spread our message.

LB:

You say, “Making bread is expressing a feeling, every loaf represents the love we have towards our territory” What does bread represent to you? What elements, values and stories are expressed through bread?

MS and ES:

To us, bread is communication. Working with sourdough every day, we study changes—fermentation is always in movement. Because we experiment with different kinds of bread every day, but also because we feel different every day. We try to communicate these feelings to the people who eat our bread. Making bread is connecting things. Bread connects us to the consumer, connects us to the land and to the farmer. It’s a full cycle.

LB:

Any future projects that are brewing?

MS and ES:

We have tons of plans, projects, ideas! And it’s not strictly connected to bread. We’ve been working with beekeepers, we want to have an impact on honey by learning more about how bees affect the land. We also have projects around coffee and chocolate, different kinds of things that are not strictly related to bread.

In the end, everything has an impact on the environment and its biodiversity. The main idea is to create a spiderweb of in-between projects that maintain biodiversity and take care of the land. We are growing this network — locally and global.