Sandor Katz is a fermentation revivalist and educator. His new book Fermentation as Metaphor explores what fermentation—and the communities of microbes responsible for it—can tell us about culture, politics, religion, art, sexuality and identity.

Johnny Drain: What was the genesis of the book and how long have you been planning it?

Sandor Katz: With my heightened interest in all things fermented—mostly focused on literal fermentation of foods and beverages, I started noticing articles where people would make reference to phenomena that had nothing to do with foods or beverages using the word fermentation as a metaphor.

When I looked in the Oxford, English dictionary, it turns out that since the 17th century there are surviving examples of using ‘fermentation’ in a figurative way to describe anything sort of bubbly and excited, and that could be an individual, a group of people, a movement. It could be a musical or artistic movement. It could be a political or social movement.

I’ve been trying to think expansively about fermentation and how the literal phenomenon of fermentation related to the figurative ways that we use the word. This book has really been fermenting in the back of my mind for many years.

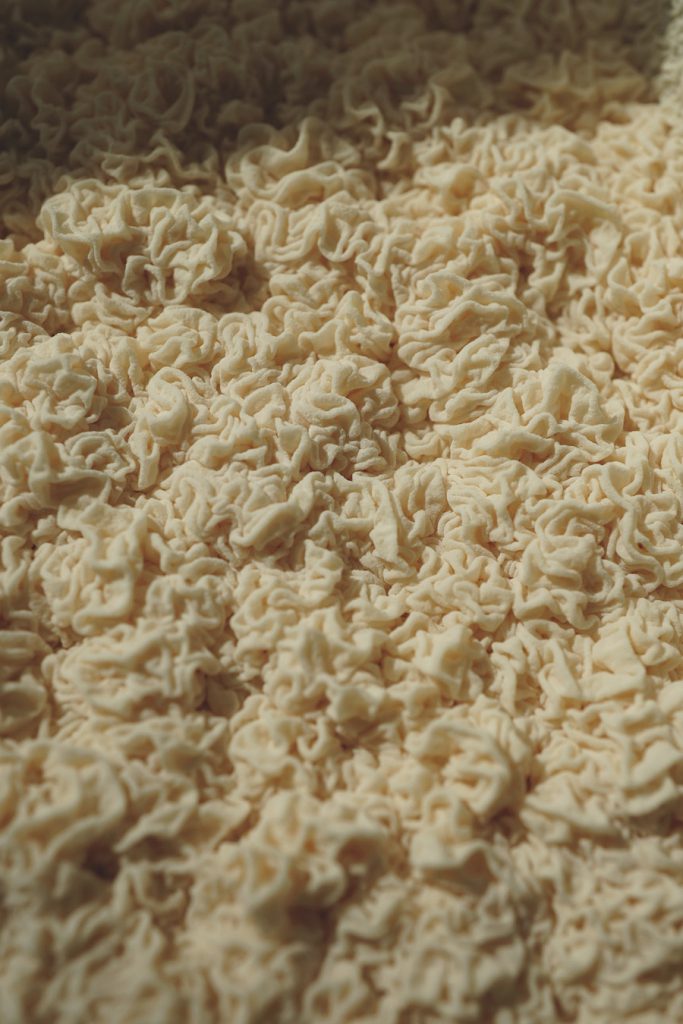

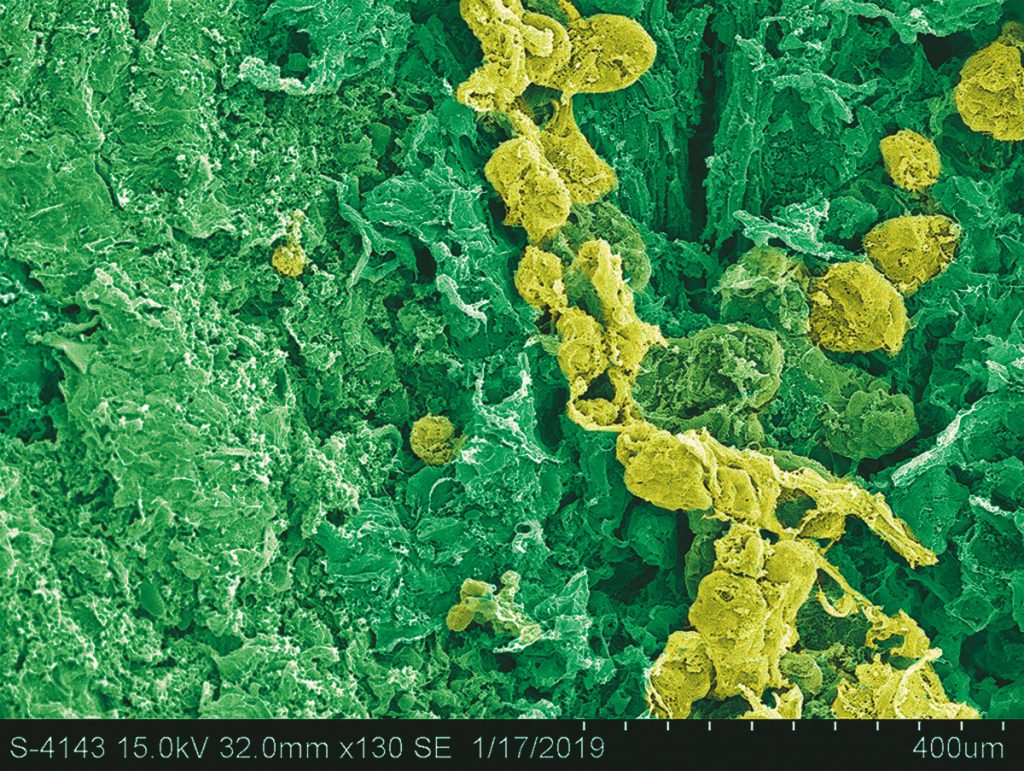

We got around to putting some of the stuff down on paper and it occurred to me that my reflections on these ideas could go very well with microscopy. Seeing microscopy images helps break down the idea for people. So we put together a system at home where I could photograph some of the foods and beverages that I was producing and connected with people at a nearby university with a scanning electron microscope that I could access.

I think one of the things that people struggle with often with fermentation is that it involves microbes which, in many manifestations, are non-visible to the human eye. People struggle with things that they cannot see—and that extends to abstract cultural concepts as well. So I think having those visuals in the book really anchors it.

For sure. We have created tools that enable us to see what has always been there, but has always been invisible, and I think it’s really important for us to recognize that life exists on all these different scales. So many of them we can’t see, but that doesn’t mean that they’re not there. If we could look at our skin under high magnification, we would see that we are host to this incredibly complex universe of beings and the same is true of all of the food that we eat.

The biological world is this embodiment of complexity. Thanks to these new technological tools, we have a growing sense of the complexity of life at smaller scales and how important they are, and how larger forms of life depend on the activity of such vast numbers of smaller organisms.

You described fermentation as activism. How do you see the future of food being changed by fermentation, whether literal or metaphorical?

The primary thing that makes home fermentation activism is that it forces people to be active participants in creating food they’re going to eat. Our existing food system centralizes the growing of food and the transformational processing of foods, and encourages us to be in this passive role of consumer.

So the process of procuring food is that you go to the supermarket or the specialty shop and depending on how much money you have in your pocket, you’ll have a lot of choices or very few choices. I recognize that we do have this system of food, mass production and distribution, and for better and for worse it functions as long as it functions.

COVID-19 has demonstrated the limitations of this system as we saw disruptions in the supply chain and certain products becoming scarce. This centralized food system is inherently vulnerable to all kinds of disruptions. Not only viral pandemics, but things like a spike in fuel prices, war, or natural disasters. When we centralize our food production, our food security is only as secure as those systems of distribution. My perspective is that the only real food security is regionalizing food production.

I’m certainly not an absolutist. I don’t think that people should only eat foods that come from within a certain number of miles of where they live. But I think that everybody would have greater food security if every region of the world was working to expand its productive capacity for producing food.

Obviously you can’t produce everything everywhere. But there are a lot of things that you can grow. Grassroots movements like we’re seeing in relation to fermentation are a great way for people to take a first step of moving away from this role of consumer and becoming active participants in the production of their own food.

One person making a jar of sauerkraut is not going to radically change the food system, but it is a first step. It’s very subversive when people get involved in producing something along the lines of a fermented food in their home kitchens in the context of this system of mass food production.

You talk in the book about how food can be an incredibly potent mechanism for building and strengthening communities, which I think we’ve seen in the last six to nine months is as vital, if not more vital, than ever?

Food is critical as an aspect of our economy and the way we’ve structured our society. This food system is environmentally destructive, wasteful and it’s producing products that are nutritionally diminished. We have to change this. Home fermentation is not the singular answer, but I think it can be a very important step in people’s attempts to reclaim food. Once the ideas begin to ferment in people’s minds they can think, “I can buy some vegetables that were produced at a nearby farm” and “I can spend a little time in my kitchen salting them. Then this mystical process is taking place in the vessel in my kitchen, and then I have this wonderful, nutritious remnant of the warm part of the year that I can use to nourish myself and my family through the rest of the year.” It begins this larger process where people might then ask, “What else could I do that would be further reclaiming food? How can I extend this feeling and this action in bigger and broader ways?”

I also love the idea of producing something that has a cultural lineage—in multiple senses—and the act of making it connects you to people who made that kraut or kimchi 500 years ago. Recipes, including these ferments, are a type of meme.

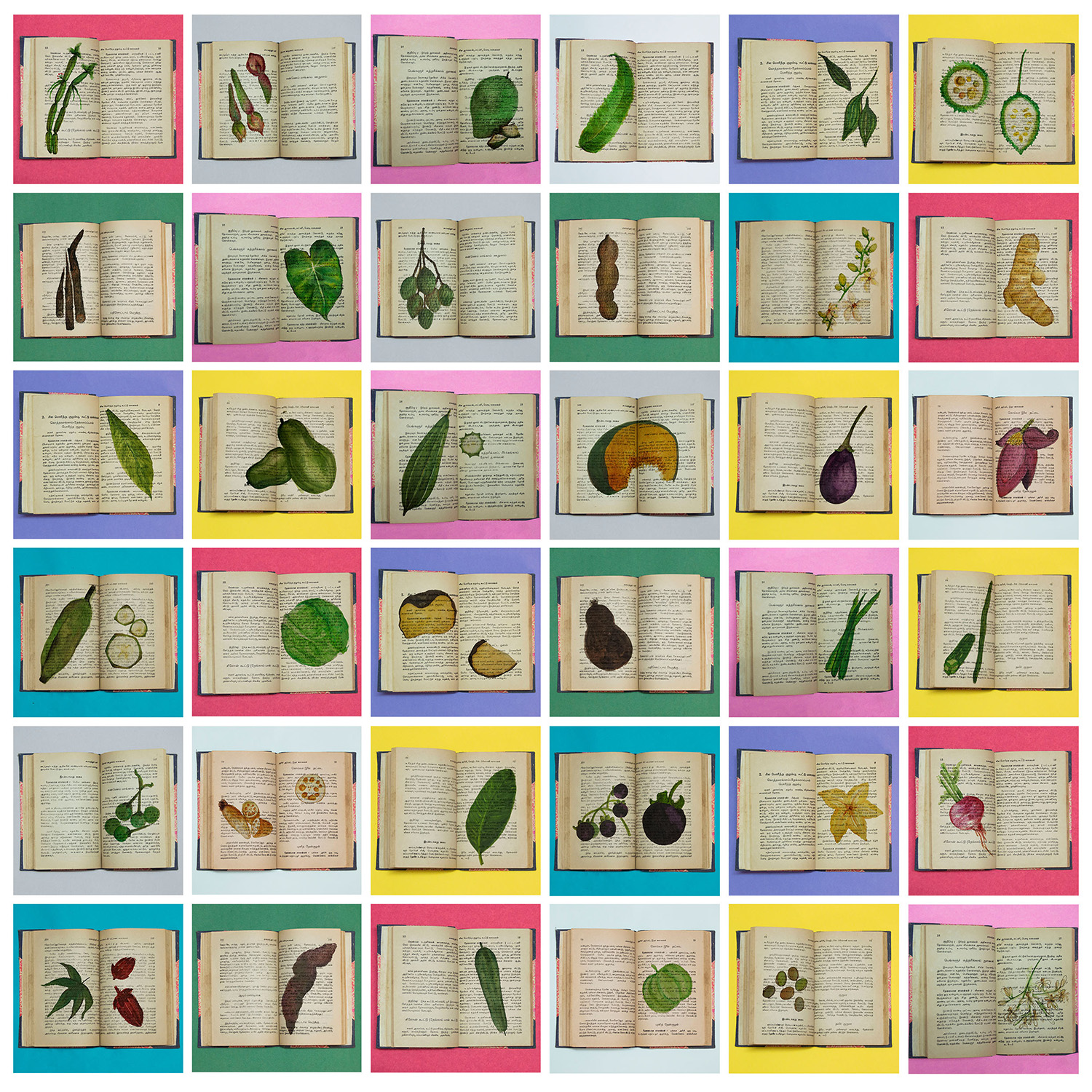

Fermentation is practiced everywhere. It’s integral to food traditions in every part of the world and it’s really a critical aspect of how people make effective use of the food resources that are available to them. That’s true of sauerkraut and kimchi and other styles of fermenting vegetables, but it’s also true of the ways that we ferment grain. Sourdough has a long tradition. Other ways of fermenting grains like the Ethiopian style of injera is an analogous process. Likewise, the South Indian process of fermenting dosa and idli. In all parts of the world there are traditions like this. For many people it becomes a vehicle for reconnecting or resurrecting lost cultural trends, family and tradition. In some cases, just people getting interested in a fermented food or beverage from another part of the world and celebrating a different cultural tradition.

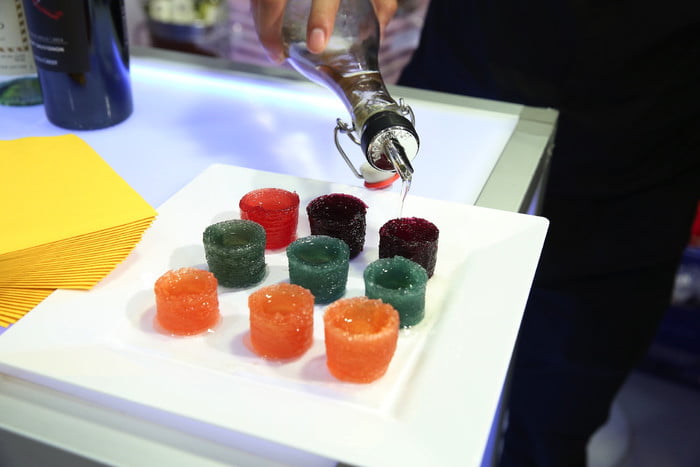

We’re also seeing exciting cross-cultural fertilization happening. There’s a lot of innovation. Nobody’s invented any new fermented foods or beverages for hundreds or possibly thousands of years, but there’s a huge amount of innovation right now, as people are taking ancient processes that have been typically applied in one specific way and applying them to some different ingredient or in some slightly different way.

The word ‘germ’. I use it less these days, but when I was a kid I remember my mother using it a lot, and I’d never really thought where it came from. You describe it coming from the Latin root germinis meaning to sprout. What has that term come to mean in our society?

The most ancient use of the word germ is to describe the part of the seed that is going to germinate and develop into a new plant, a new seedling. In the world of brewing beer, for example, that process turns out to be critical because what we would call malted barley is really just barley that has begun to germinate bringing about enzymatic changes that break down complex carbohydrates into simple sugars and enable us to get a significant amount of alcohol from the grains.

Since the late nineteenth century and the early observations of microbes as vectors of disease, the idea of the ‘germ’ has come to encompass the germination of the microbe in our bodies which becomes the cause of disease. So the word has come to mean something negative and our parents might tell us to “be careful of germs” or “wash our hands to make sure that we don’t have germs on them.”

That shift towards it being largely a negative word is interesting.

I grew up in the midst of the war on bacteria, hearing that bacteria are our enemies or that they need to be destroyed by any means necessary, but since around the turn of the new millennium, with the human microbiome project, there’s been a much broader recognition that we can’t really think of bacteria as our enemies, because we’re so reliant on bacteria for our functionality.

If you look to evolutionary biologists, there’s a broad consensus at this point that all multicellular life is evolved from bacteria and archaea, which are another sort of early single cell form of life. We’re recognizing that trillions of bacteria that inhabit each of our bodies are essential for our survival, our wellbeing, our continued existence. Future medicine is all about probiotics and the idea of using bacteria to address very specific health problems.

Right now in the midst of COVID-19, we’re transferring the war on bacteria into a war on viruses. And again, it’s overly simplistic. Yes, here’s the virus that is creating a problem for us. But the main thing that is keeping bacteria in check in the world are viruses and so viruses are just part of the balance of life.

Germs! Germs are everywhere. Germination is important.

We picked out a couple of words—germs and bacteria—there that often carry negative connotations. ‘Mutation’ is another one that I think most people think of as being a bad thing, but actually mutation is the reason why we have all of this diversity in life. And the reason why humans are humans. One of my favorite quotes in the book is “mutation is the creative force of nature.” Could you unpack that a little bit?

Our traditional view of evolution is that there’s some inevitable accidental mutation and if it turns out to be a beneficial mutation then it results in a superior specimen that is going to be more successful at reproduction. And so what we see in the world, the bright, aromatic flowers, the butterflies, the birds: all of this biodiversity is the result of mutation and the mutations that are not beneficial end up getting lost because those organisms with those non-beneficial mutations typically are not as successful at reproducing.

So mutation is absolutely a driving creative force of nature, but it’s not the only one. I’ve been reading some interesting books that are emphasizing the cooperative aspects of nature.

What lessons could humans learn from microbes with respect to cooperation, adaptability and resilience, which we might think of as being hallmarks of microbial life.

Well it’s not just microbes. There’s so much cooperation and collaboration in the natural world. Lichens, which are everywhere, are a sort of fungi with amoebas joining together to create a functionally different form of life. Lichens have capacities that neither of them could have, individually.

All multicellular forms of life involve cooperation between different life forms. We are used to thinking of ourselves as individuals: you are Johnny. I am Sandor. But each of us is like a bacterial superstructure. We each are hosts to somewhere around a trillion micro-organisms and without them, we wouldn’t be able to function at all. We wouldn’t be able to exist.

They give us many of our functional attributes and, going back to the first multicellular organisms, the first eukaryotic cells, the broad, general thinking is that one type of single-celled organism engulfed another type of single-celled organism, and developed a mutually beneficial living arrangement of one living inside of the other, which got sort of institutionalized as eukaryotic cells. But these multicellular organisms never lost their association with the single-celled organisms that generated them. And so with or without us being aware of it, this is just the way the world works, biologically speaking.

I think that as science has given us a window into this and greater awareness of this we can really make use of our increasingly sophisticated understanding of the complexity of the biological world, and draw some inspiration from it.

Right at the end of the book you took about this idea that the future belongs to the flexible. How do you see that as it applies to the global food system?

I definitely wrote that in the context of thinking about food in particular and ways that food is likely to change, whether it’s due to climate change or different conditions that make what’s traditionally been grown there, perhaps impossible, but that also creates new possibilities for other things that can be grown and forces us to think about different kinds of food resources.

It’s funny. In the last week or so, as it’s begun to get colder, stink bugs have been everywhere. You’ll get a blanket that you haven’t used since last year and hundreds of stink bugs will fall out of it. They hide everywhere.

I happened to be looking through this book that I have about edible insects and it turns out there’s a technique for removing the stinky stuff they release when they feel threatened and that, actually, you can eat stink bugs!

Some of my friends are horrified that I would ever be thinking about eating them, but for me the question is, what is the most abundant thing in the environment? And right at this moment, it’s stink bugs. If we can figure out a way to turn the things that are overabundant in our environment into food that can satisfy us and sustain us, that seems ideal. Maybe that means we have to let go of some of our cultural ideas about what’s appropriate to eat. And as we go through changes, not all of them will be comfortable or easy.

Not only in regard to food, but in life in general, the future belongs to the flexible. Things are going to change. What we see as normal, how we sustain ourselves, how we live, how we structure our society, has got to shift. Some people won’t be able to move with the inevitable changes whereas other people will be more successful at adapting, and I do think that they’re likely to be the survivors.

When I visited, it was a similar time of year and I was overwhelmed by the colors of the thousands and thousands of trees that you are so lucky enough to be surrounded by. With the onset of autumn, what are you most looking forward to eating? And fermenting?

While I’ve been watching the stink bugs come out I’ve really been devoting a lot of my time to processing chestnuts. We have three chestnut trees outside the house and yesterday I made chestnut porridge—just chestnuts water, butter, a little salt—I have chestnut flour which I used to make a wonderful chestnut cake the other day, and I made chestnut koji. I’m really committed to using what’s abundant. In a couple of weeks, I’m going to be making my annual trip to my friend Jeff Poppen’s biodynamic farm. We’ll be filling up a pickup truck with radishes and fermenting that.