The word idli elicits different responses from different people.

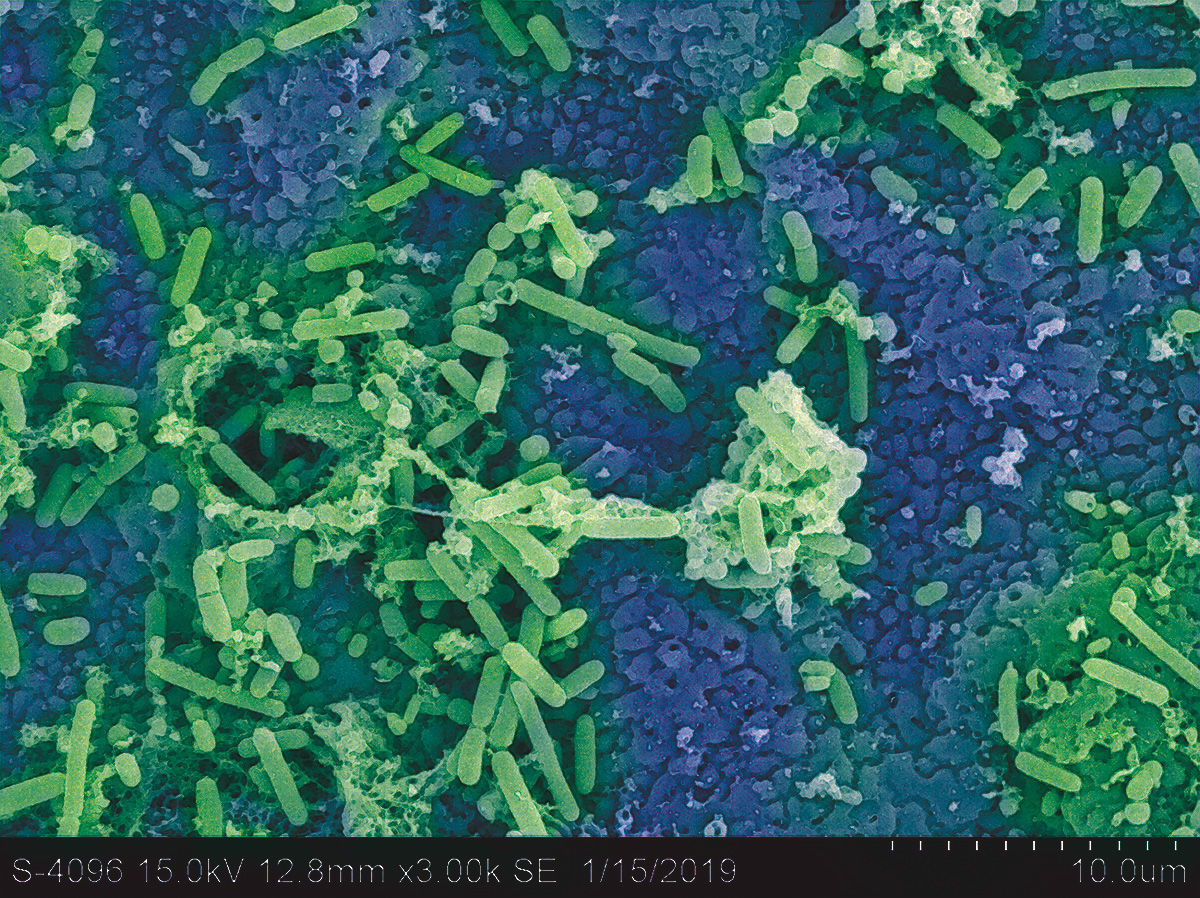

A south Indian breakfast staple, idli, or fermented rice cake, is comfort food for some, an incarnation of boredom for others and a taste of home for many. When broken down to its elemental level, there is really nothing much to say about the idli. Rice and black gram beans (and a few other ingredients) are soaked and ground to a fine batter and left to ferment for about 6-10 hours, depending on environmental factors including temperature, humidity and elevation. The fermented batter is then scooped onto platters with four (or more depending on the make) circular depressions, where the liquid sits comfortably before the plates get stacked and deposited into a steamer. After 15 minutes of sauna, fluffy, white, soft idlis emerge. In a sage-like manner, the rice cakes soak up the essence of what is around them—a spicy chutney of coconut and green chillies, a dry spice blend mixed in oil or a piping hot tamarind and lentil-based soup-like dish called sambhar. When done right, the last bits of the idlis are used to sponge off whatever accompaniment is left on the plate.

Although accurate, this comprehensive summary of the idli-making process does little to elucidate how the dish continues to baffle its creators. The moment seasoned idli makers find themselves face to face with a picture-perfect idli, a quick round of discussion on batter proportions and steaming techniques ensues. The perfect idli seems to be the south Indian equivalent of a pie in the sky.

In a sage-like manner, the rice cakes soak up the essence of what is around them…

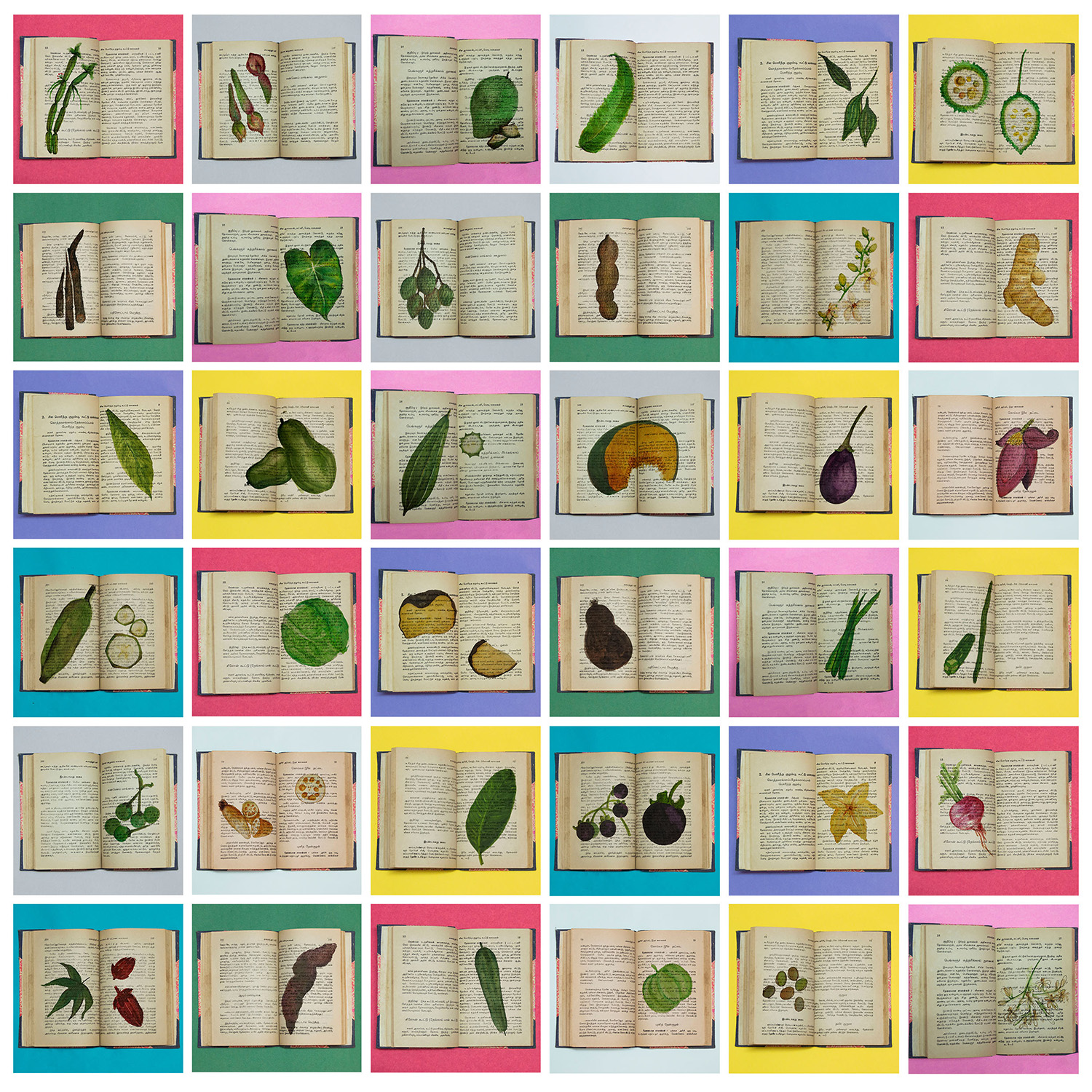

According to food historian K.T. Achaya, the earliest known mentions of idli can be found in Vaddaradhane, a prose that dates back to 920 AD. Written in the south Indian language Kannada, idli is referred to as iddalige here. A description of the process published in 1025 AD mentions black gram soaked in buttermilk, ground to paste and spiced with asafoetida, cumin, coriander and pepper. While early mentions of idli mainly focus on black gram, Achaya postulates that between the 8th and 12th century, cooks who accompanied the Hindu kings to Indonesia brought back fermentation techniques, evolving the idli making process. Rice was probably added to this milieu to ensure better fermentation. The state of Karnataka also gave birth to the semolina idli; popularly known as rava idli. Driven by a shortage of rice during World War II, Bengaluru’s iconic restaurant chain Mavalli Tifiin Rooms (MTR), used semolina as a substitute to make idlis—an emblematic reminder of wartime innovation.

Although idli evocates the image of pristine, white cakes, regional nuances add a range of characters to the genre. In her cookbook Coconut Grove, an ode to the coastal city of Mangaluru, chef and food writer Deepika Shetty shares recipes for idlis made using various ingredients and steaming techniques. Between its pages, one can find batters with toddy, cucumber or jackfruit pulp steamed in stainless steel cups, jackfruit leaves, turmeric leaves and banana leaves, creating a motley assortment of idlis. “Beyond breakfast, idlis are also a meal for us,” shares Shetty. “We eat jackfruit idlis with a spicy accompaniment and the idlis are mostly soaked in some gravy, what we call rasa,” she adds. Another variation is the Ramassery idli made using rice sourced from the Palakkad city in Kerala. Cooked over earthen pots covered with a muslin cloth, the idlis are de-moulded with a specific leaf, imparting a unique flavor to the dish. There’s more, like the Kanchipuram idli (spiced batter, cylindrical in shape, steamed in Bauhinia variegata leaves), Mallige idli (soft, named after the jasmine flower) and the Chiblu idli (steamed in small bamboo baskets), to name a few. The idliverse does have a lot to offer.

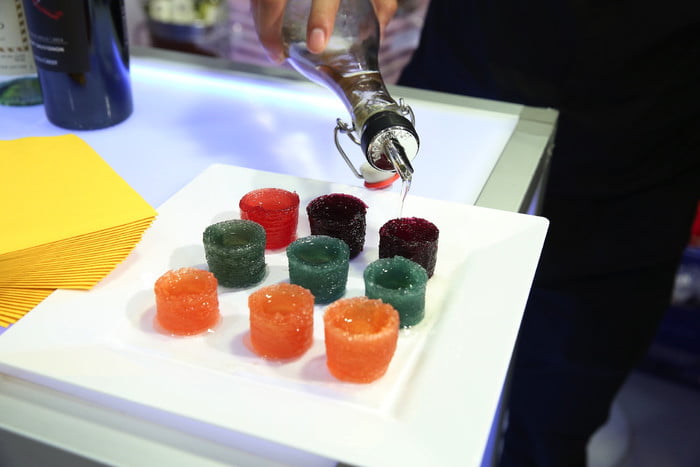

Nothing says care like a plate of idlis. For many families, idlis slathered with oil and spice powder are the go-to travel meal. In recent times, parents have found ways to hide vegetables by innovating colored idlis for their children. When the family bemoans at the sight of the same ol’ idli, the cakes are chopped up and sautéed with onions, bell peppers, and sometimes even a dash of ketchup, to add a touch of newness. If the stomach refuses to, well, stomach anything, idlis are slid over as the best option. Millets, traditional rice, quinoa, vegetables and chocolate! The internet shares an idli for your every ingredient query.

As the idliverse expanded to add some familiar and some new ingredients, the domestic idli making tools began to shrink and fit neatly in our kitchen cupboards. “Idli batter used to be made every day as there were no refrigerators,” reminisces Shetty. She talks about the laborious process of grinding the batter as women sat in front of large stone grinders, deftly turning the pestle with one hand as they slid the grains using the other. The stone grinders are no longer a familiar sight in Indian kitchens, and the laborious process of physically rotating the pestle has been handed over to the power of electricity, paving the way for wet grinders.

C.R Elangovan, a historian based in the south Indian city of Coimbatore, unearthed an important chapter in idli’s evolution when he chanced upon the origins of the invention. The author of ‘Automatic Aataangal: Kovaiyin Seethanam (Automatic Wet Grinders – Coimbatore’s Gift) shares that sometime in the 1950s, P. Sabapathy, a mechanic from the city decided to automate the grinding process to reduce the burden on women. Using an external motor, he designed the grinder such that the bottom vessel moved circularly, as the pestle remained still. While his prototype was bulky and expensive, over time, other manufacturers worked on the equipment, making them more compact. Today, sleek tabletop versions of the grinder have become a common sight. In 2005, the Coimbatore Wet Grinders & Accessories Manufacturers Association applied for a Geographical Indication tag for the product, earning a stamp of authenticity for this unique invention. Elangovan adds that apart from the invention, Sri Lakshmi Industries in the city played a significant role in mobilizing the product, making it a ubiquitous domestic appliance across south Indian kitchens. Wet grinders became an essential part of the bridal trousseau, crossing borders with her.

In the outskirts of Bengaluru lies what’s touted to be the world’s largest batter factory. Popular food brand iD Fresh Food’s website reveals a state-of-the-art facility where sanitary lab-like conditions produce enough raw material to make about 24 lakh idlis/day (2.4 million idlis/day). Apart from iD, a range of other options exist in the market, significantly bringing down the idli making efforts. If that still doesn’t suit your purpose, you can always walk into one of the smaller eateries and demand a plate of idlis any time of the day or night! After all, what are 24-hour idli shops for, if not for your 2 am idli pangs!

Krishnan Mahadeva, who runs Bengaluru’s popular Iyer Idly store, grew up around the batter business. His father set up the enterprise in 2001, initially selling homemade batter. He then turned it into an eatery where people could quickly get a plate of idlis (steamed on muslin cloths) and coconut chutney, both made using the wet grinders. When his father passed away in 2009, Mahadevan and his mother took over the reins, and today the enterprise whips up close to 2500 idlis on the weekends. According to Mahadevan, idli is a fascinating dish as it is light on one’s stomach and their wallet. “Other foods momentarily satisfy your cravings, but idli is not like that. It is healthy and it leaves a lingering impact.”

Perhaps the most fitting summary of idli’s journey can be found in entrepreneur R.U Srinivas’s food venture, the Idli Factory. After sourcing batter proportions from seasoned home chefs, Srinivas got custom silicon-based idli moulds made to produce travel-friendly, bar shaped idlis! Idli’s past moulded to fit the needs of our present.