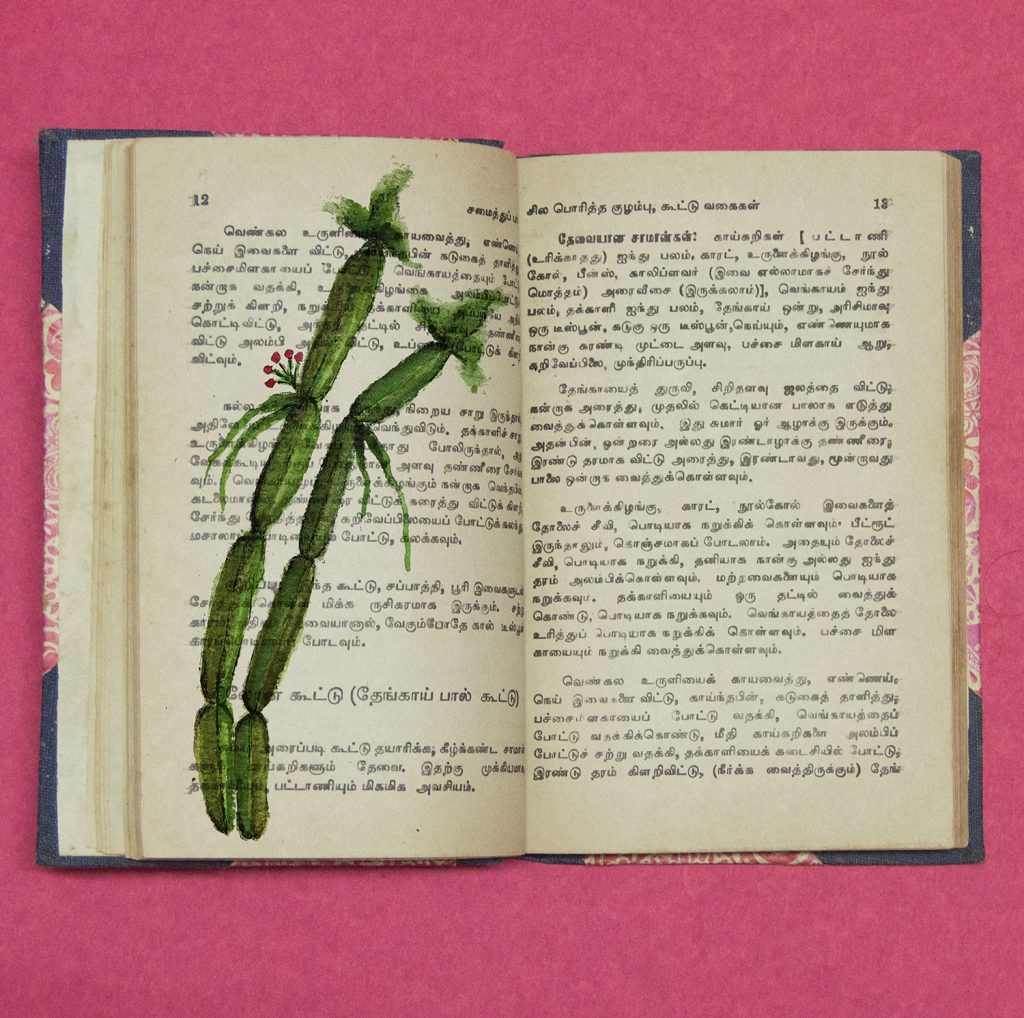

In southern India, regional lore has it that a new Tamil bride’s trousseau is not complete until it includes a copy of S Meenakshi Ammal’s Samaithu Paar. The title translates from a Tamil phrase instructing beginner home cooks to, literally, ‘Cook and See.’ The legendary cookbook written in the 1950s contains recipes for every day vegetarian dishes traditional to the Tamil Brahmin community. When freshly-minted food designer Akash Muralidharan returned home from Milan where he studied for a Masters in the subject to Chennai, Tamil Nadu and found his mother’s old copy of the cookbook along with letters from her mother containing recipes—what Muralidharan calls, “age old versions of food blogs and YouTube videos”—it sparked a series of food investigations.

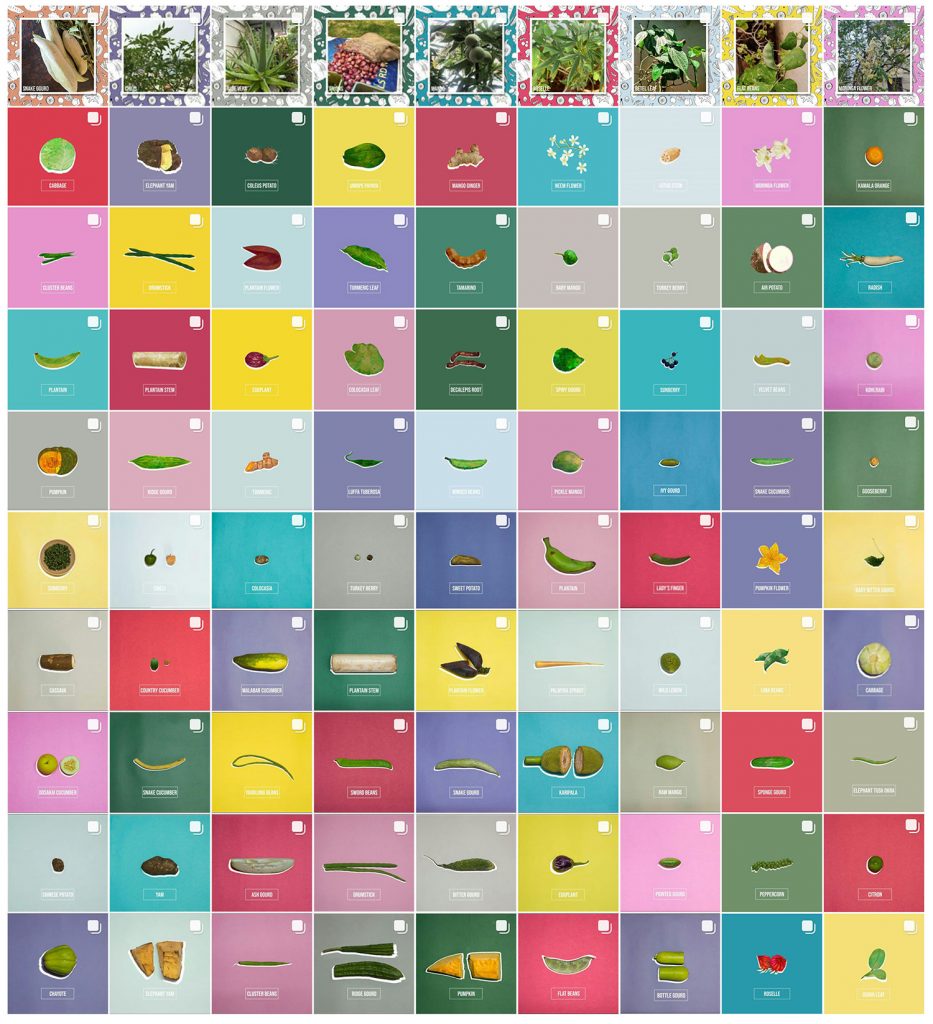

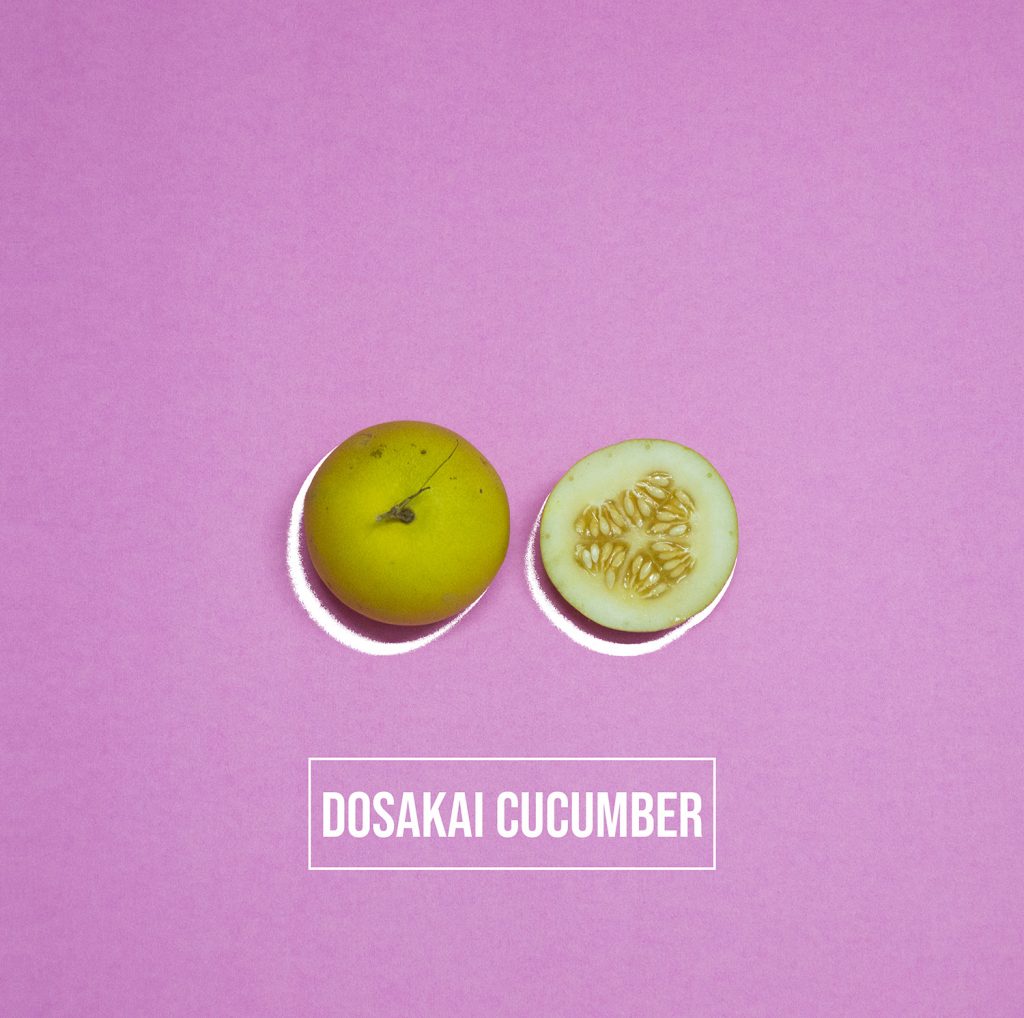

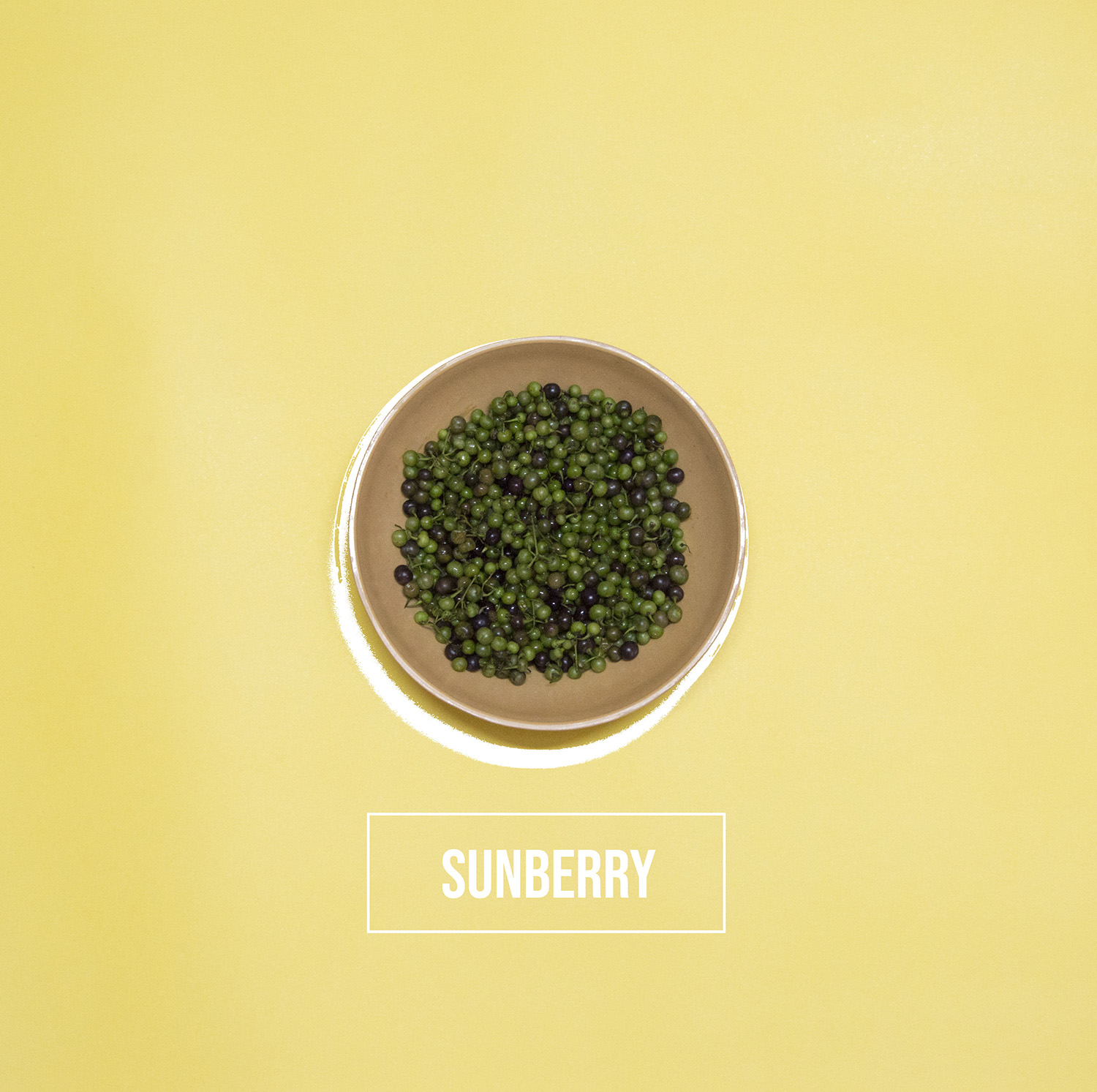

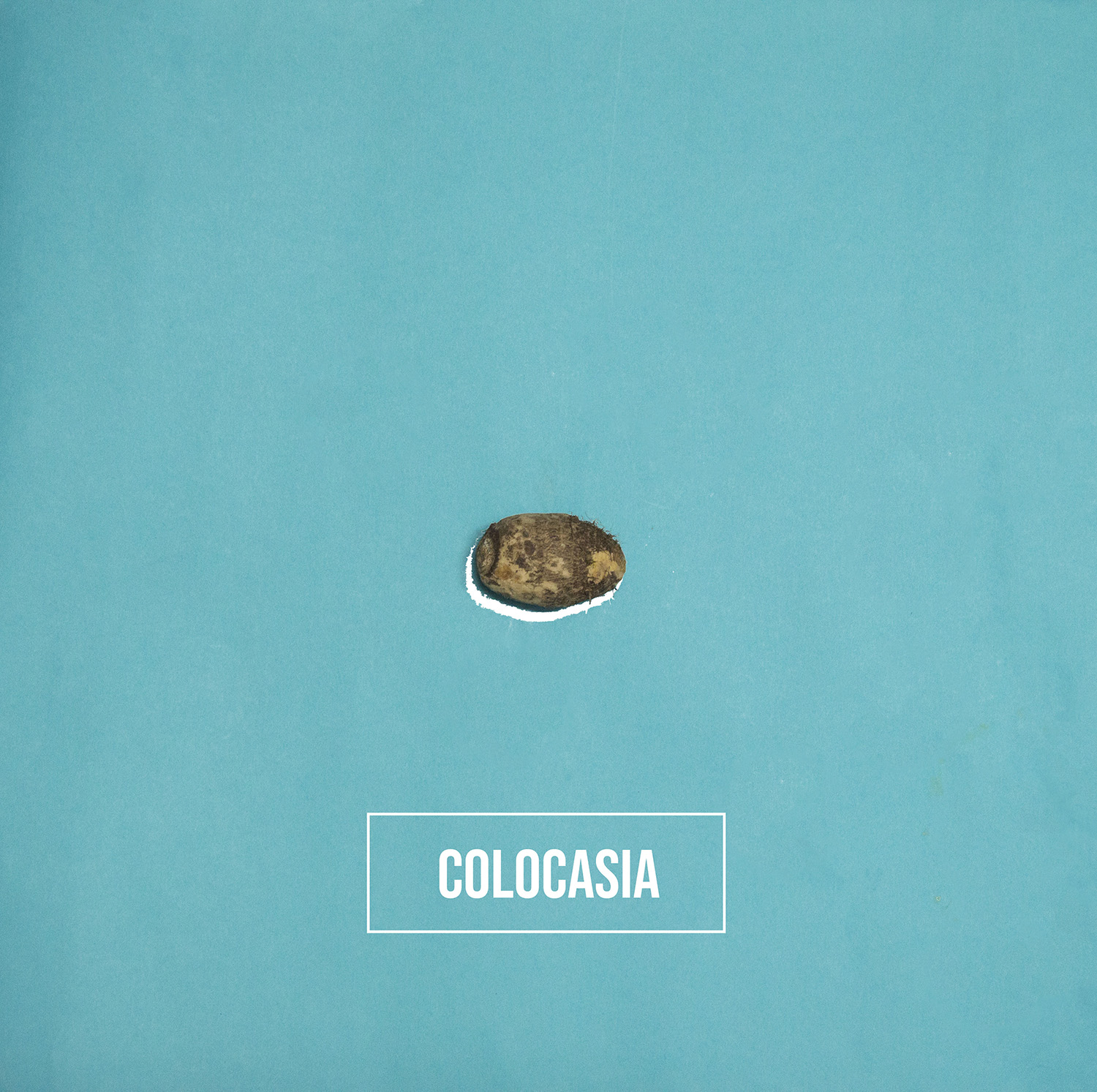

While going through the recipes in Samaithu Paar, Muralidharan discovered that many of the vegetables that were once kitchen staples were no longer readily available in the market in a metropolitan city like Chennai. Some were not even cultivated commercially anymore—what were once local and seasonal ingredients had become almost exotic. These “underused” vegetables, as Muralidharan calls them, included both seasonal and perennial vegetables like gooseberry, Malabar cucumber, ivy gourd, plantain flower, clove beans, decalepis root and tubers like elephant yam and Colocasia.

Inspired by the film Julie & Julia, where blogger Julie Powell attempts to cook all the recipes in Julia Child’s iconic book, Mastering the Art of French Cooking over the course of a single year, Muralidharan started his own 100-day long project on “missing” vegetables in early 2020. The COOK and SEE challenge was to cook recipes from Samaithu Paar using these underused, “forgotten” vegetables while attempting to answer questions as to why such vegetables, their nutritional value and taste factor firmly established for generations, had fallen out of favor in city kitchens. He looked at these vegetables from the perspective of the home cook, the person who decides the menu for the day for themselves or their family, and the challenges faced by them in procuring some of these ingredients in cities where access to backyard vegetable gardens, a common feature in village homes, is limited.

Muralidharan’s project took place on Instagram, where every day he posted an illustration of a different vegetable and a video of a home cook—his mother—making a dish from Samaithu Paar with that forgotten vegetable. In the captions, he wrote about the vegetable, its different uses and names in other Indian languages, and where available, some history of origin culled from his research. The timing turned out to be uncanny: in under a month of starting his project, COVID-19 would change everything, and the need to think deeply about local, seasonal and previously underused ingredients would become more necessary, especially across the cities of the world. With supply chains severely disrupted because of nation-wide lockdowns, ingredients and vegetables that were grown locally became the fresh produce most easily available, unlike the wide choice of produce from around the world that city consumers would have had access to otherwise.

Muralidharan is still working his way through the information he has gathered and is not yet ready to conclude why these vegetables have become scarce in city kitchens. “At the beginning (of the project) we assumed that these vegetables were not well used in kitchens because consumers were not planning their meals effectively, and there was a gap in transfer of recipes,” he said. These remain probable causes, coupled with a genuine lack of time to cook traditional recipes that are often time consuming. This trifecta of lack of time, lack of availability and access to these vegetables (itself a result of their decline in popularity) and a lack of knowledge of cooking with these ingredients has slowly led to these vegetables becoming underused in cities.

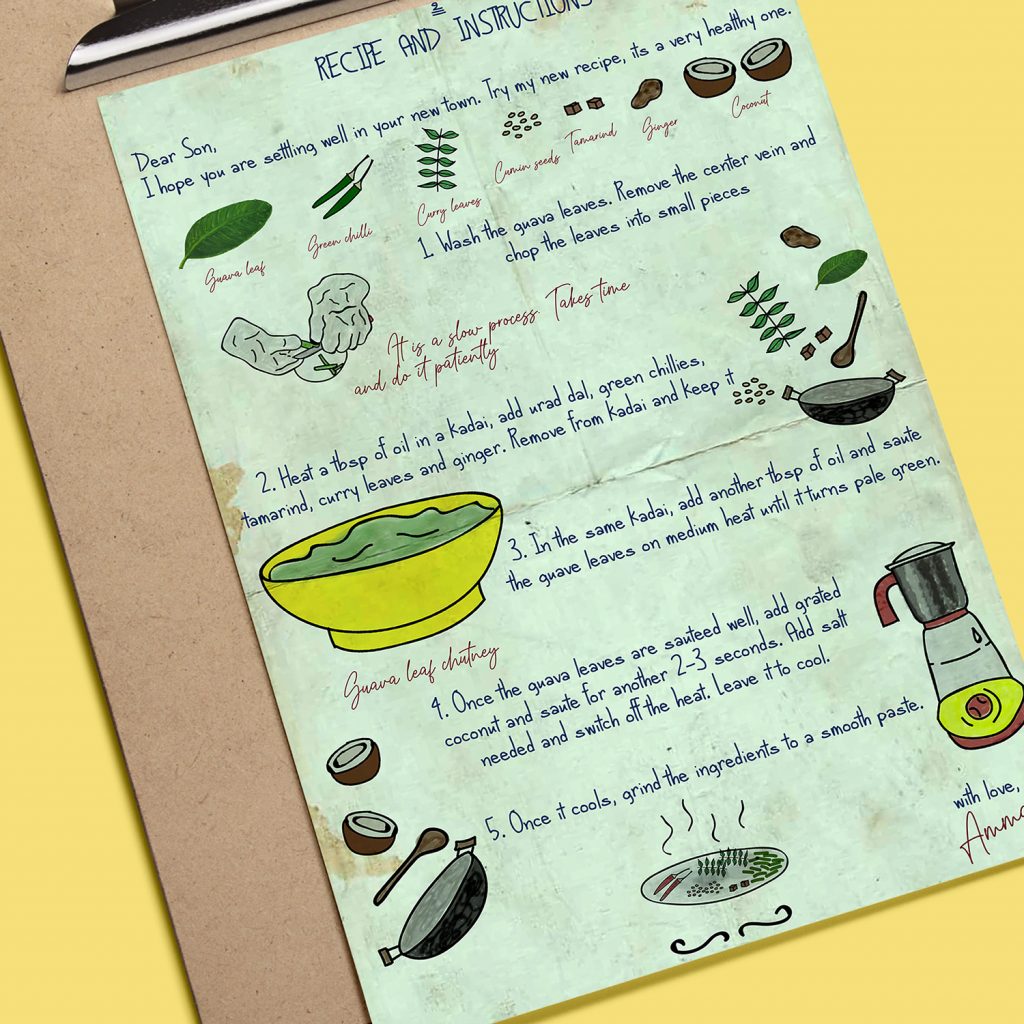

Recipes, before they became more widely distributed through the internet and cookbooks like Samaithu Paar, were typically passed down from mothers to daughters and daughters-in-law, most bequeathed orally. When written down at all, rarely were they more than a flexible set of instructions. This absence of formal recipes fostered an intuitive way of cooking that encouraged each cook to customize a dish in endless ways. COOK and SEE paid homage to this legacy of recipe exchange. In the first phase, the videos of his mother cooking is a montage of sounds and scenes of and from the kitchen. Her face is never shown, but her hands are swiftly shelling peas, there is music in the background, conversation between other members of the family, shots of boys playing badminton on the grounds outside, birdsong, and the many sounds of cooking—spices hissing in hot oil, the blender whirring and the whistle of the pressure cooker. These are not recipe videos, but for those familiar with Indian cooking, it isn’t impossible to figure how the dish of the day was made from these brief videos.

About half way into the 100-days project, Muralidharan was forced to tweak the work. When going out to procure vegetables became impossible by around day 45, he continued the project through illustrations superimposed on pages of Samaithu Paar, animations of the vegetable of the day, and through recipes drawn on images of blue inland letters. The last phase was given to foraging for underused ingredients like moringa flowers and betel leaves, and examining what the act of foraging looked like in cities.

Half a year after the 100th day on Instagram, Muralidharan is now sieving through the research material he has gathered. Placing his learnings so far entirely in an urban context, he said that he worked with some 80 commonly known vegetables during the making of his project, yet only about 20 could be procured easily from supermarkets and street vendors.

But access to certain vegetables was not the only challenge facing home cooks who were looking to recreate dishes from Samaithu Paar. Less than 70 years after it was written, the cooking techniques referred to in the book often seemed unfamiliar or too time-consuming to include in a regular menu. Drawing on conversations with some 40-odd home cooks, Muralidharan is currently processing his findings by creating archetypes to fuel further research and insight into home cooking behavior. Many of the home cooks he interviewed over the age of 30 learnt recipes from elders—mothers, aunts, in-laws—while those in their 20s were still learning to cook. “These kinds of home cooks learn from YouTube videos, blogs, etc. where they don’t have a personal relationship with the person giving the recipe. They are thus already losing out on some knowledge regarding traditional recipes,” he noted.

On Instagram, Muralidharan has been posting illustrations of what he calls the archetypes of cooks, assigning each of them a name, “to crack the case of missing vegetables.” “Kamala” is the masterchef, who knows her way around the kitchen so well she could cook with her eyes closed. “Brinda” is the busy cook who couldn’t care to experiment, but has a home cooked meal on the table every day. “Shakuntala,” the pragmatic cook is all about innovation and experiments, while “Shakti” is bold and spirited in her approach to food. “Mythili” cooks to survive, and “Nataraj,” the only male in the list of archetypes, is a cook of convenience who shutters between making himself something and using food delivery apps. Muralidharan wants to use these classifications to understand the behavior of home cooks.

Muralidharan has plans to introduce charts with these “missing” vegetables in schools, to teach children about the diversity in food from an early age. Later next month, he is part of a crew that is designing an “atypical, experimental” menu at a wedding in Chennai, using these underused vegetables. “Weddings and restaurants are great teachable places to popularize these ingredients,” he said. Towards this end, his current research includes interviews with chefs to innovate recipes and inspire people to change food behavior. At some point, when it is safe to do so, he wants to travel outside of cities to research food behavior in other regions in the state. Muralidharan is ultimately working to encourage demand for these vegetables to make them city kitchen staples again, while exploring ways to bridge the gap in supply to create lasting changes in consumer behavior.