At the beginning of the pandemic, I was puzzled when I first saw dalgona coffee pop up on my Instagram feed. To me, dalgona was a candy that was nostalgic but not quite delicious. It was something my grandmother and mother had once craved, but it was a food that I, as a child growing up with access to ice cream and gummies from the corner store, wouldn’t really choose for myself.

As my own friends tried their hand at the dalgona coffee recipe, they reported sentiments that more or less mirrored my own. “I mean, it’s instant coffee and sugar,” they rationalized. Flavor-wise, I feel similarly about dalgona, which is just sugar and baking soda. But the significance of food draws not only from its taste but also from layers of nuance and context—what kind of space it has occupied in history or national memory, and who is consuming it. With this context, the reinvention of dalgona into dalgona coffee holds a slightly different importance.

In Korean, the name dalgona sounds like a revelation, meaning “Oh, it’s sweet.” Sweeter than sugar on its own, there’s not much more to the candy’s flavor profile. Its simplicity is fitting for a treat invented in a time of food scarcity that followed a devastating civil war steered by foreign powers. Some accounts report that dalgona first started circulating in the late 1950s, on the tail end of the Korean War, and other accounts say that it was popularized in the seaside city of Busan in the early 1960s.

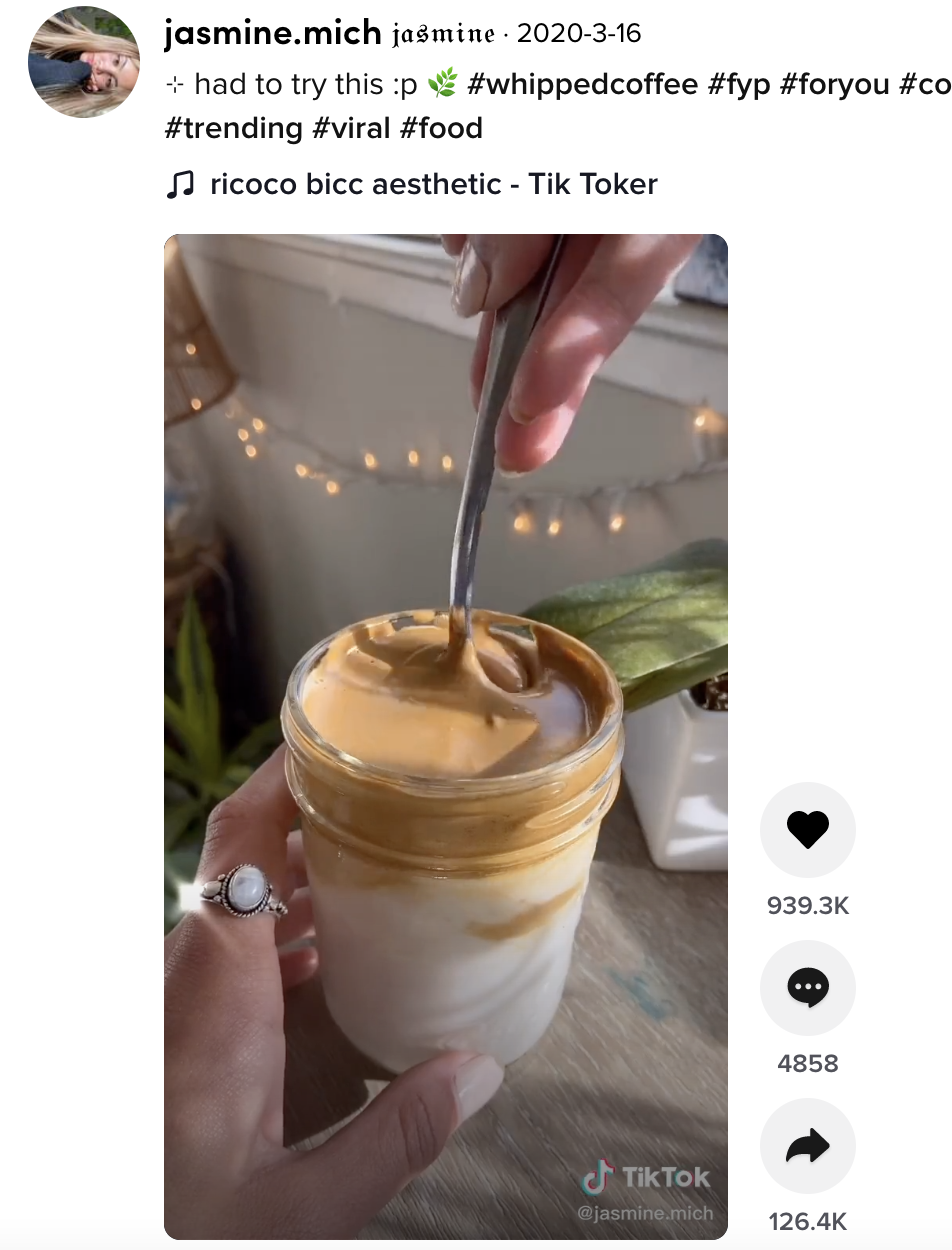

Dalgona coffee doesn’t actually contain dalgona. It’s made by stirring together instant coffee, sugar and water until it expands into a toffee-colored cloud, which is then scooped onto a cup of cold milk. Traditional dalgona, on the other hand, is hard and brittle. A Korean variation on honeycomb toffee, it’s a street treat made by melting together water, sugar and baking soda, sold for as little as 500 won (about 50 cents) apiece. Also known as ppopgi, it can come in the shape of a flat lollipop with a simple shape pressed into it (a star, a car, a heart). If you can snap the dalgona in half without breaking the shape, the seller might offer you another as a prize.

In her 1998 autobiography My Sister Bongsoon, author Gong Ji-young recounts a childhood spent eating dalgona in the late 1960s:

And, around then, I likely spent much time at either Sungjin Comic Books or Ddobok’s Ddoppopgi Stop, melting white lumps of corn syrup or yellow grains of sugar into the treat we called dalgona.

In those early days, dalgona was cheaply sold and cheaply made. Adults could turn a small profit by setting up shop with a coal briquette on any street corner, and kids looked to it as an inexpensive and readily available dessert. When I was younger, my grandmother told me about meals that began with scrounged rations from American military bases and ended with dalgona, which was, to her, a fancy dessert. But when I walked around Seoul with my mother, she would steer me away from dalgona stands, which have become increasingly less common. “It’s unhealthy food, toxic food,” she would scold, even though my grandmother would gossip to me that she had eaten more than her fair share in her own childhood. In the early 1960s, sugar was still hard to come by, and even as late as in the 1980s, not all vendors had access to food-safe cookware; as a result, some dalgona would be made with corn syrup substitute in tin ladles that molted over the heat. In Korea, dalgona remains a nostalgic treat, but it is a reminder of poverty, of making do in a time of recovery from the trauma of war.

The origin of dalgona coffee can be traced to a January 2020 episode of a Korean variety show called Pyeon-storant (a portmanteau of convenience and restaurant), in which celebrity guests engage in friendly competition to showcase the simplest and most delicious recipes. One celebrity guest takes the cameras all the way to Hon Kee Cafe in Macau, where the owner makes him a drink whipped from instant coffee. “Wow, it tastes just like dalgona,” he remarks, taking a sip. This revelation lit up Korean social media; people began trying the recipe at home, and cafes started adding it to their menus.

In fact, dalgona coffee is not just dalgona coffee, but also Chow Yun-Fat coffee, named for the legendary Hong Kong-based actor who visited Hon Kee Cafe in 2004 and fell in love with the drink. It’s also Phenti Hui coffee (a popular drink with its own history in India) and Greek frappe (which was invented in 1957). It’s a simple and unconventional take on instant coffee with a bounty of disparate and coexisting identities. Its meteoric rise to Instagram fame by just one of these names is a curious example of influencer foodways—the forces that increasingly govern how we encounter and “choose” what to make and eat, especially in a time of sharing food online rather than in person.

The algorithm conveniently serves up a dish, and we dig in without a second thought. Our dominant foodways are no longer governed by scarcity, by the principle of making do with what we have, but rather by social media algorithms and influencers. In a landscape so heavily defined by these actors and technologies, it is easy to lose track of the context of what we’re consuming, omitting what makes certain foods what they are in the first place. Alessandra Gordon of Seattle-based bakery Ayako and Family discussed on Instagram her experience of sharing her family’s Japanese recipe for shokupan for publication in Bon Appetit, only for it to be renamed “milk bread” in print—an English moniker deemed to be simpler than the original name, despite the fact that the recipe contains no milk because it originated during a time in Japan when dairy was expensive and difficult to access. Gordon describes the effect of this renaming by pointing out an ironic comment from a reader on the recipe that was ultimately reproduced: “if yours has no milk, it’s not milk bread.”

There have been many critiques written of a tendency in the food world that is often called “Columbus-ing”—when typically white and upper-middle class people “discover” a food that has long existed in another culture or “reinvent” it in a way that goes against the original. Many of these critiques view the phenomenon as a willful offense, whether by mainstream publications or celebrity chefs. Although this can sometimes be the case, we also need to examine how the broader social practice of cooking, consuming and sharing food has changed to seat this phenomenon as the new cultural norm. While sharing recipes can be a positive way of sharing culture with new audiences, it can result in the reduction of dense histories into something judged to be more palatable and likely to take off, especially when the work of interrogation and introspection is left out of the equation. And what can seem like an innocent new name for a dish can serve, unfortunately, as an act of redefinition, of setting a false standard that tracks more closely to a biased or simplified idea of what it should be rather than what it really is. What results from the normalization of these assumptions, more than anything, is a net cultural loss: more and more, we consume without understanding what we are consuming because we buy into the misconception that what is simple and light is best, and context is nothing but extra weight.

Food trends take off because they are aesthetically interesting and accessible. But it’s too easy to generalize this new facility and make the mistake that context is what bogs down a food, renders it unadaptable, when often the context is exactly what makes a food interesting.