Foraging in the modern urban landscape can serve many functions. Most obviously, it is a strategy for finding food but beyond that, it can offer an accounting of the environment and the things living within it—a way of mapping an ecosystem. As more and more designers are scrutinizing the ever-sprawling urban environment, and its viability as a long term, resilient living space in an ecological crisis (not to mention a pandemic)—foraging has been found to be a useful tool.

At this year’s Dutch Design Week, among the many projects and exhibited works that discussed sustainability, food, and life in the pandemic—foraging was a strategy repeatedly touched on. Similar to tapping into local material resources, the exploration of foraging among designers at DDW signals not only the use of creative methodologies for solutions to increasingly precarious supply chains, but also indicates that designers are starting to pay more attention to their immediate environments to better understand the world—and its life.

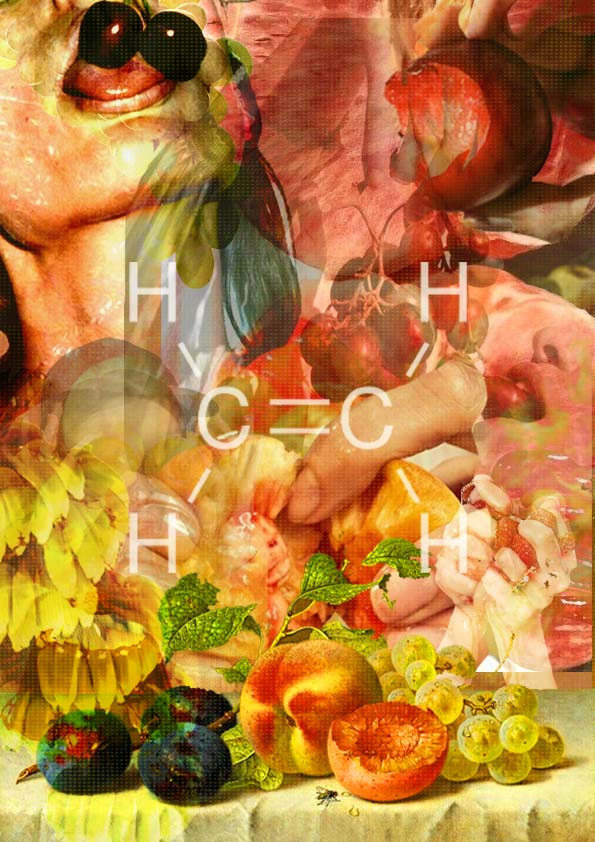

For designer Panita S., finding the time and space for a study in foraging came with the outbreak of global pandemic. “It is quite ironic at the peak of quarantine when everyone is hoarding for essentials in supermarkets around the world.” said Panita S., “Meanwhile, with this piece of wilderness in my neighborhood, I [saw] it as an alternative food source just like a mini organic market with various arrays of species.” Panita’s foraging journal, Tenderly, produced in collaboration with graphic designer Delphine Lejeune, serves as an “ode to modern foraging” in Europe—from a Southeast Asian perspective.

Foraging is highly dependent on where one is, and because it is such an ancient practice, knowledge of how and where to do it, varies widely. To offer some introductory instruction to the practice, London-based Bompas & Parr was brought in by IKEA to present a workshop on foraging and using the finds to make “park juice” at home. At IKEA’s Virtual Greenhouse exhibition, foraging was seen as a tool that can help serve to create a healthier life in the home, as they are “exploring the concept of a 15 minute radius, designing our communities to provide everything we need from energy consumption to resources.” says Jenny Lee, leader of communication for IKEA’s Life at Home study, “In terms of healthy homes we foresee that access to green spaces will be prioritized with outside and inside better integrated and nature playing a bigger part of how we live.”

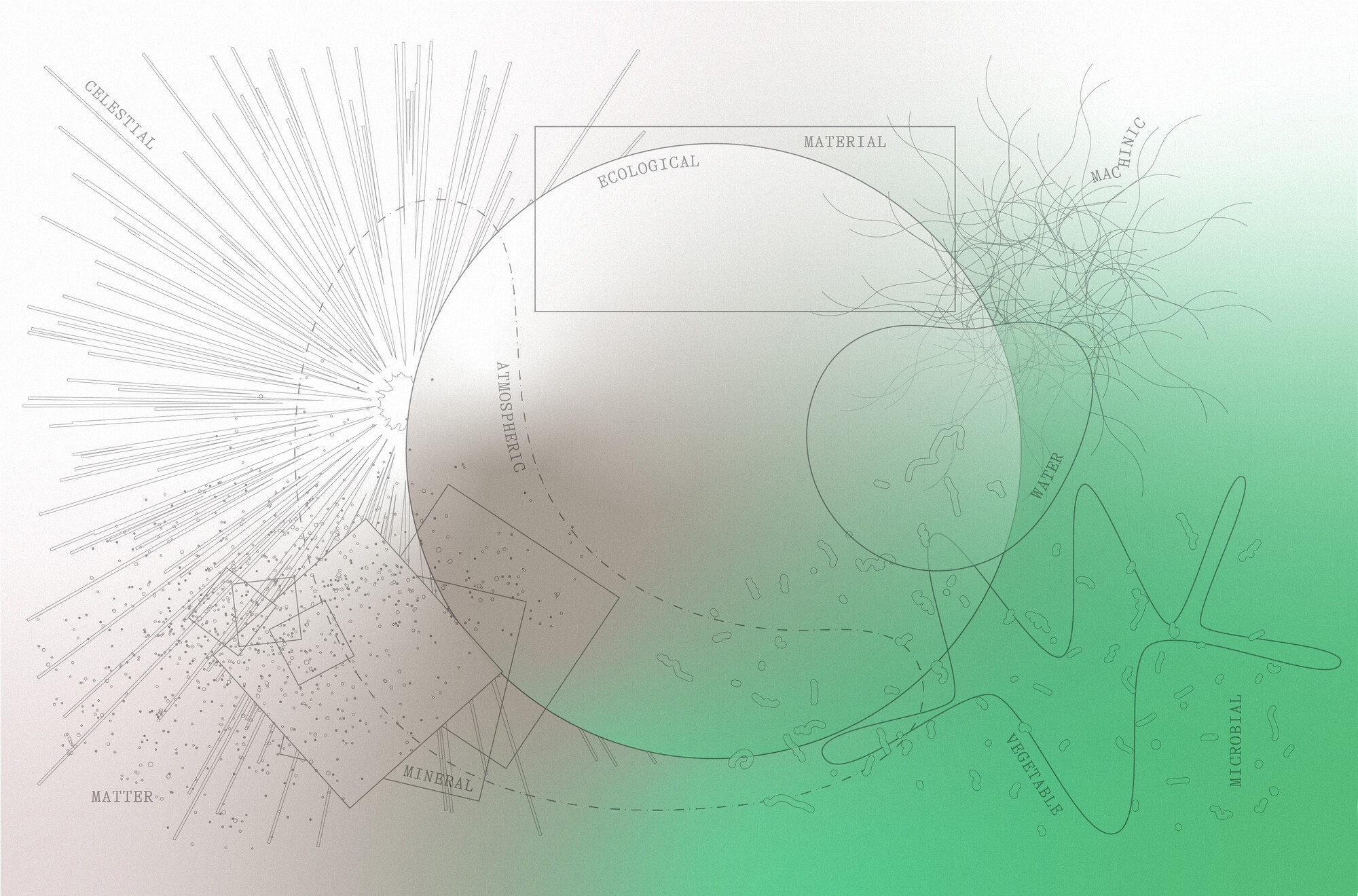

Integrating foraging strategies into day to day life in the urban environment, requires a great deal of critical examination. “The problem here is precisely that cities are not designed for this. They’re not even designed for humans but for cars, let alone food and plants.” say María Fuentenebro and Mario Mimoso of Sharp & Sour design studio. In their speculative recipes for Urban Foraging, Sharp & Sour researched the potential for foraging in urban environments like Barcelona.

While the project is a clear illustration of how the many people living in urban environments are seriously disconnected from any healthy ecosystem, the benefits of designing spaces for more species stands to benefit people greatly, “this is not the solution to world hunger or poverty,” says the pair, “But it’s a cheap and easy way to teach our kids about agriculture, it would make everyone connect and value our planet and its gifts more, and it would help reduce pollution levels—both from the food supply chain and the cities themselves.”

From the work exhibited at this year’s DDW, it’s clear that designers are starting to seriously explore what can be gained from sourcing food and other materials directly in the urban environment. This year, the pandemic has no doubt been a serious test of autonomy in cities around the world—no doubt as ecological crisis continues to shake our supply chains, the resurgence of foraging culture may show us better ways forward. “Foraging has taught me about self-reliance and resilience in a scarce time.” says Panita S., “It brought me to my senses once again.”