Thinking about the world that we are in today – heavily industrialized, reeling under the Weather with a capital “W” and with a pandemic-in-progress, no less – begs a response to this question: is certainty even possible anymore? In food, people are seeing changes in the way they cook and eat due to climate change’s effect on supply chains and food systems. What then happens to a country’s traditional food culture? The Center for Genomic Gastronomy’s (CGG) New National Dish (NND) project explores how the culinary landscape might change to something new altogether, or revert to something ancient and now-forgotten.

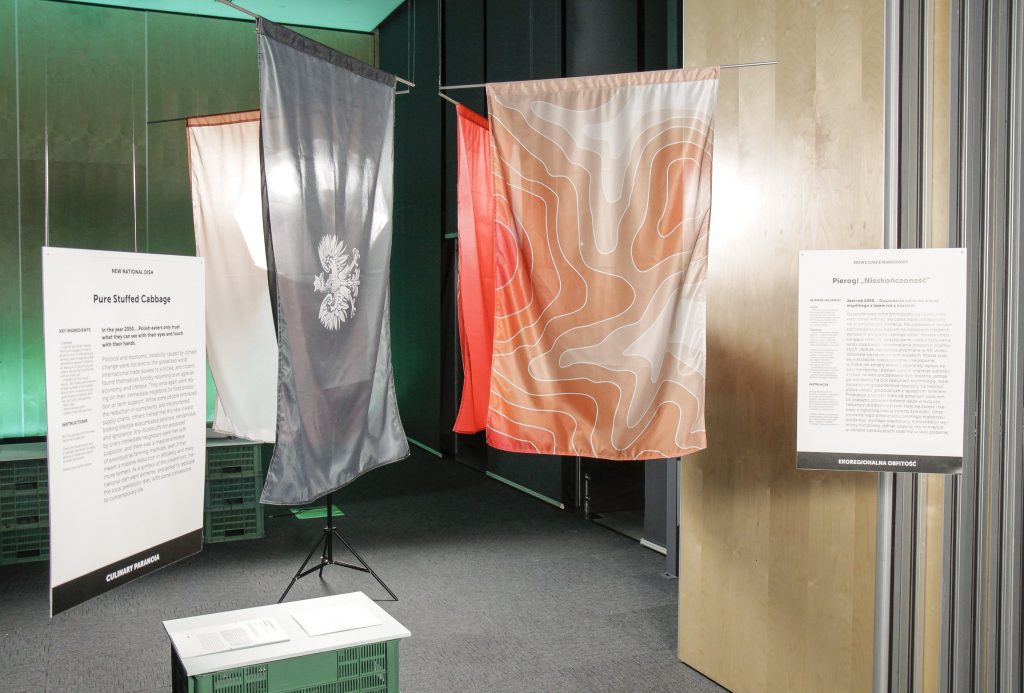

Experiencing this work is a surreal experience. While CGG, an artist-led think tank, imagines a future for different countries affected by unpredictable weather, which they’ve coined as weather weirding, in the years 2030 and 2050, their forecasts of cultural changes decades in the future could be used to describe our present times. The project started in 2018 when CGG designed a new national dish for Portugal for the year 2050, and has since, included iterations in Poland, France, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), and Norway. CGG is to open a permanent installation at Centrum Nauki Kopernik (Copernicus Science Centre) in Warsaw, Poland later this year.

The concept of a single dish for a whole country is an idea fraught with uncertainties: how can any dish represent all of a country’s diverse communities and distinct food practices? Food is as much an emotion as it is sustenance. Coupled with how severely climate change affects agriculture and migration, the question of a singular national dish is a thorny one. For the artists behind the project, forecasting is not an act of predictions, but rather a set of stories, recipes, scenarios, and “edible futures” that consumers, farmers, policy makers and other actors in the food cycle are invited to imagine and react to. CGG started with the idea that human beings shape the planet through everyday choices they make in what to grow, trade, and eat as well as through the food memories and stories that are celebrated, shared, and passed on. Through this project, CGG recognizes that the food supply chains these countries rely on will inevitably change due to climate change, and as a result, traditional recipes will have to evolve. The artists came up with different futures, keeping in mind that any new dish needed to be highly resilient to such weirding conditions.

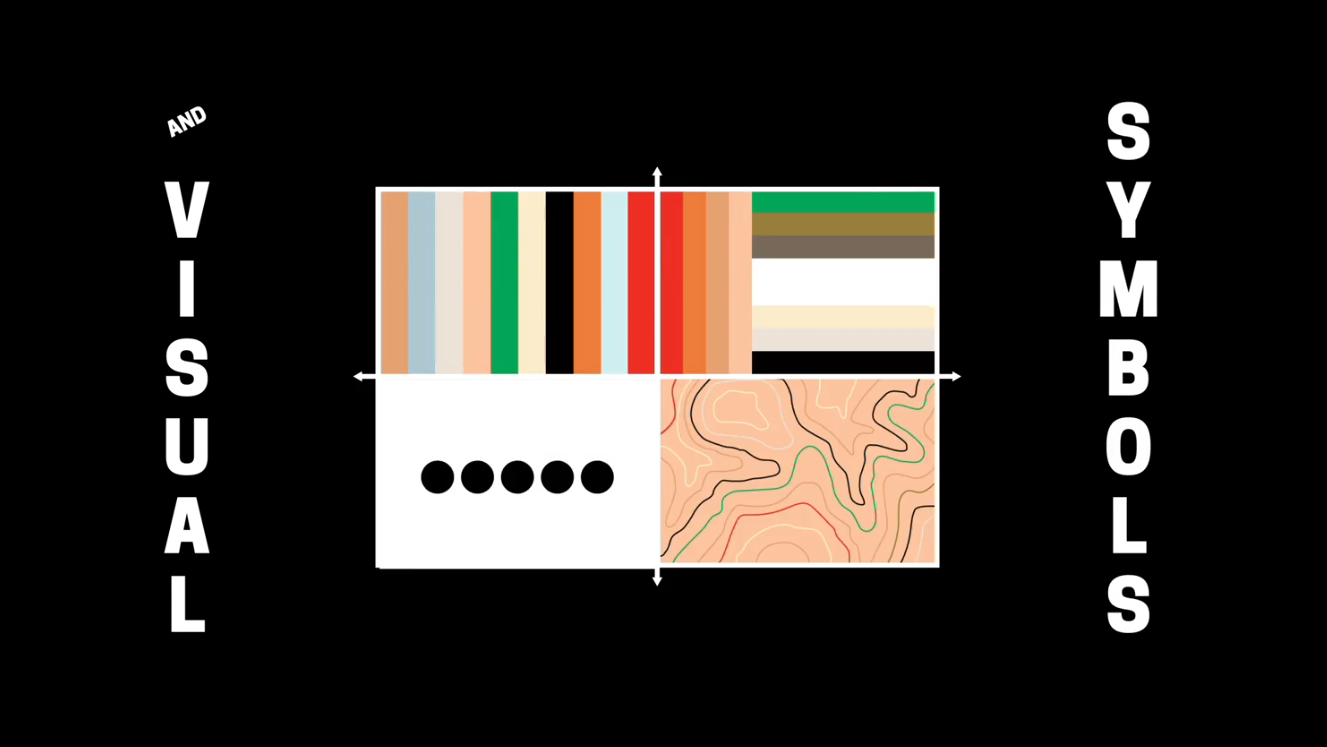

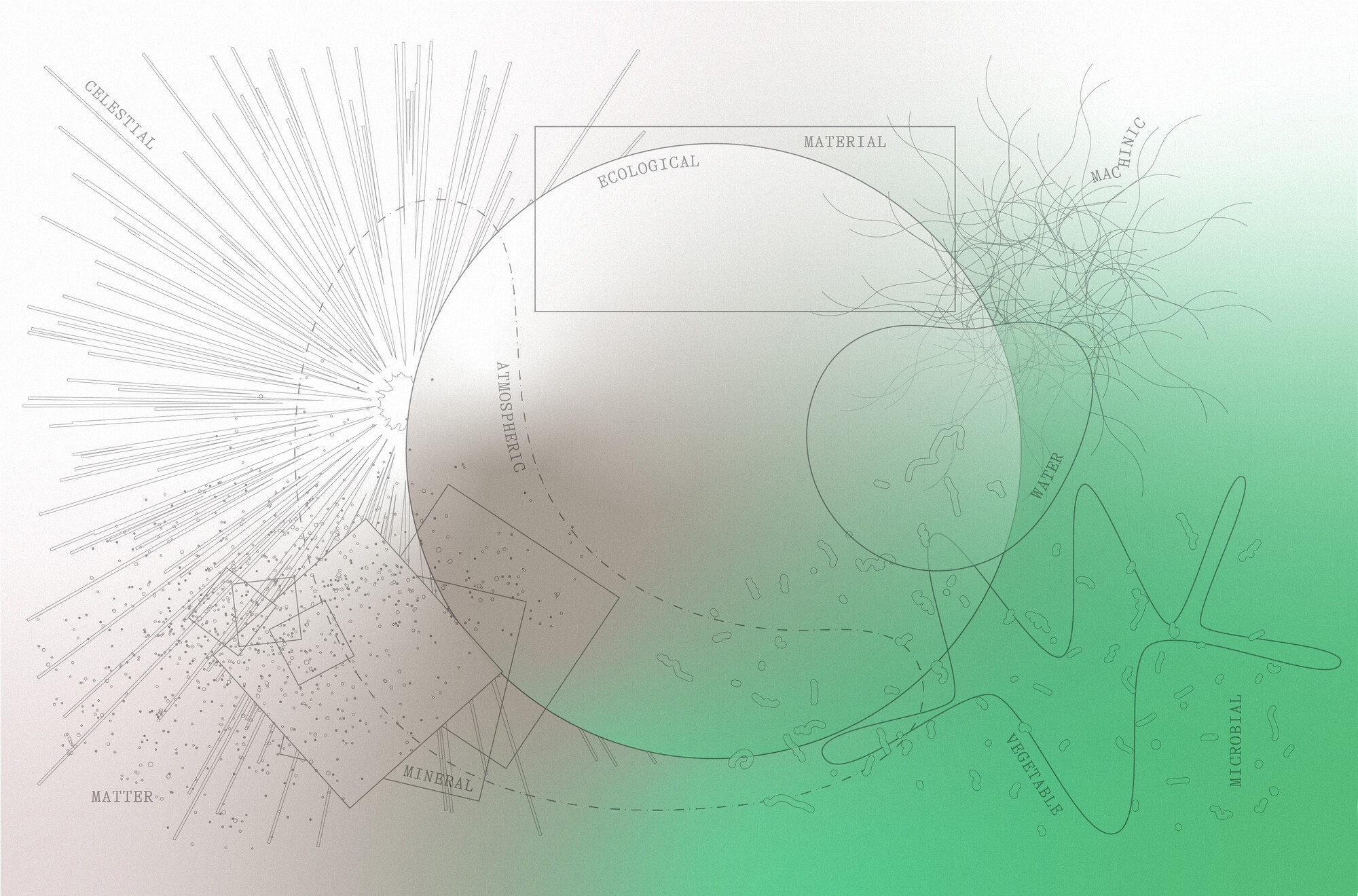

The resulting scenario planning framework – a methodology that uses sets of stories, recipes and flags to detail four possible directions the national dish may take in response to socio-economic, political and environmental changes – uses a 2×2 matrix to question what happens when various driving forces – climatic and human – interact with each other. Assuming climate change as the main driving force, the artists used changing cultural attitudes toward technology and changes in the national political and economical environments to name four futures for people to work with.

In Food Security through Obscurity, a scenario that was part of Portugal’s matrix, the team decided to take back control from global markets and re-localize the food economy. By accounting for how unstable weather wildly affects prices, plant breeders and food activists have begun to create new seeds that would produce food varieties that are tasty, adaptable to local weather, uneven in shape and with a short shelf-life. Through this, sending produce across the world is rendered impossible, forcing Portuguese agriculture to focus on region-specificity instead of global standardization.In response to the scenario Adaptive Gastronomy, Portugal is using technological advancements to try out various farming techniques that can be instantly adjusted to changes in weather or pest problems. The catch is that citizens are asked to be Beta-Tasters, volunteers who experiment with new flavours, tastes, and ingredients. Like fashion seasons, there is something new in food every year. It is a demanding future, asking people to constantly change their habits and try new things all the time.

Culinary Eugenics is a worrying future scenario, but not one that is impossible to imagine. In Portugal nationalism is on the rise, borders are heavily controlled, immigrants and “foreign foods” are unwelcome. Here, self-sufficiency in agriculture is advocated for, requiring young people to move, or move back to the peripheral areas to farm and set up local, co-dependent food communities. The rejection and violence of all ingredients foreign in favour of what is strictly national, pure, and thus clean food disrupts the history of culinary migration. This forecast ends with a chilling warning of what the adoption of such an approach could lead to : “It is only later that explicit calls for genetic purity in humans and forced sterilization are launched.”

Lastly, in a scenario of Ecological Abundance, CGG forecasts a process of ruralization because of the stress of city living and climate impact in urban areas. In response, they propose large experiments in alternative ways to grow and eat food that do not adhere to strict geographical borders, but rather are drawn according to the land’s relationship with biodiversity and weather patterns. As a result, food systems are locally oriented, the terroir travels, and the focus is on a rural ecoregion, not on the city.

CGG has worked to adapt these broad scenarios in the other countries where they have exhibited this work. For Poland, the recipes for a possible new national dish included Kotlet Schabowy made with tissue cultured “meat” and transgenic flax seeds, Skillet Potatoes with Polish-grown olives and fungal-resistant, transgenic lemon, Pure Stuffed Cabbage that hearkens back to traditional family recipes, and finally, Pierogi Infinity which listed ingredients like pesticide-free wheat and bioregional fruits and vegetables. For the UAE, it translated into the development of four foods that citizen visitors could taste and vote on to become the new national dish in 2030. The advanced timeline, as compared to other country’s 2050 implementation date, is because the changes have been that much faster in the Middle East. Zack Denfeld, co-founder of CGG in 2010, said that the UAE was changing very, very fast. As Denfield spoke on the vertical farms, cloud seeding being done in Dubai, and the idea of rain in the desert, he said that in the techno-heavy region of UAE, there have also been concerns among people regarding the human and social cost of all these advancements.

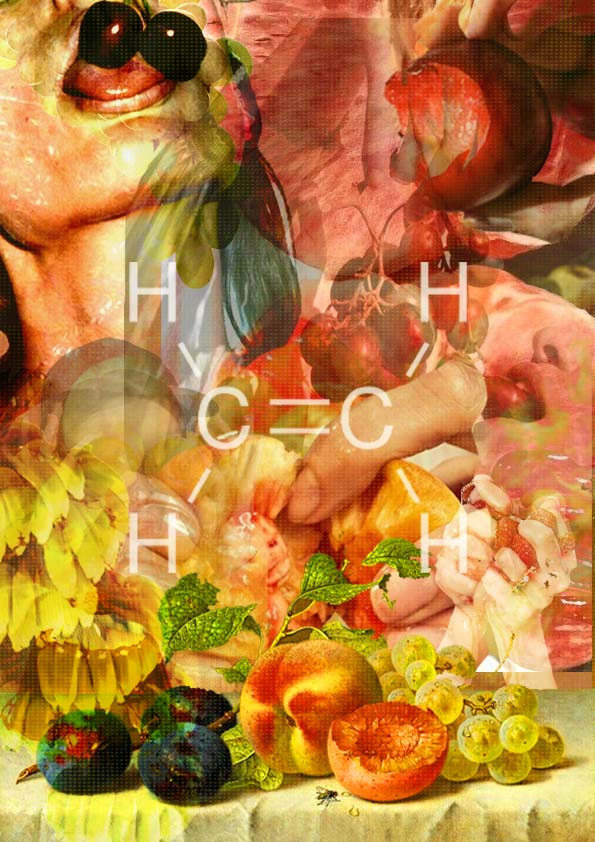

The resulting dish contenders were more global in cuisine, in keeping with the constant movement of local and expatriates in the region. Smart Farm Pizza Bites reflects the miniature vegetable breeds developed in the vertical farming sector, Personalized Tube Food has both lab-grown produce and additives from obscure sources, HY8R1D 5U5H1, where like everything else, sushi becomes hybridized, and Desert Dessert honours the region’s relationship with the desert and embraces traditional foodways.

Denfeld acknowledges that a lot of things have accelerated during Covid-19, but points out that the idea of the NND is not to be predictive, but instead is to engage with stories. “We underestimate how similar food will be (because of standardization),” he adds. There is always a sense of exclusion of the nuances of certain food cultures when one talks of assigning a single dish to a whole nation with complex scales of bioregions. Denfeld says that the project is about being a bit provocative, and using the dish as a cultural icon to facilitate difficult conversations.

As complicated and mildly dystopian as the project’s forecasted futures may seem, a lot of these scenarios are already being played out in the world, hastened even more by the pandemic. We are seeing reverse migrations, a global examination of the unsustainability and near-complete dependency of cities on resources from its peripheral rural areas, renewed focus on ‘healthier’ foods that have short, localized supply paths and smaller carbon footprints. There is too, more dangerously, a surge in nationalism that is threatening diversity in food cultures and identity. One wonders then, if the future has already arrived. If so, there is much that the NND project offers cultures to learn from: on how to cope with agriculture, migration and food consumption crises in the pandemic and beyond, as also on how people might have to rethink food systems sooner than anticipated.