Towards the end of 2021, London’s Design Museum hosted an exhibition titled Waste Age: What Can Design Do? The exhibition aimed to highlight the taboo yet prevalent place waste holds within our collective existence. Perhaps the most widely produced man-made material, waste is contrastingly the one material no one wants to claim, touch or even see. Separated into visual depictions of overwhelming statistics, hopeful designs of waste-made objects of value and fact filled walls, visitors were confronted with the scale of the problem upon entering the Design Museum through an elegant installation of 3D printed bioplastic cascading from the ceiling.

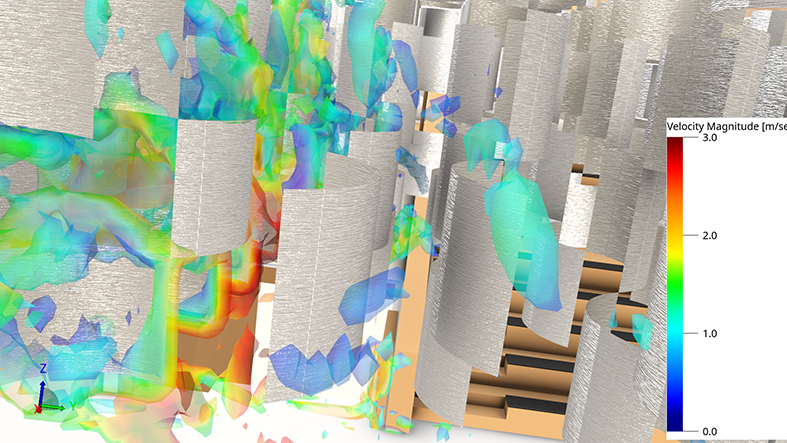

Titled Aurora, the modular installation was designed by French architect Arthur Mamou-Mani, a specialist in parametric design and additive manufacturing. The project was produced in collaboration with French design software company Dassault Systemes. Stretching across the expansive atrium of the museum, the piece included 300 modules, printed in bioplastic polylactic acid (PLA), a non-toxic thermoplastic derived from sugarcane.

This material is one Mamou-Mani is well acquainted with, having used it in projects for Milan Design Week and Burning Man. PLA bioplastics are claimed to be 80% more efficient than the industry-standard petroleum derived plastic due to being compostable, requiring less water and minerals to produce, along with the added benefit of being less carcinogenic.

Photo by Design Museum.

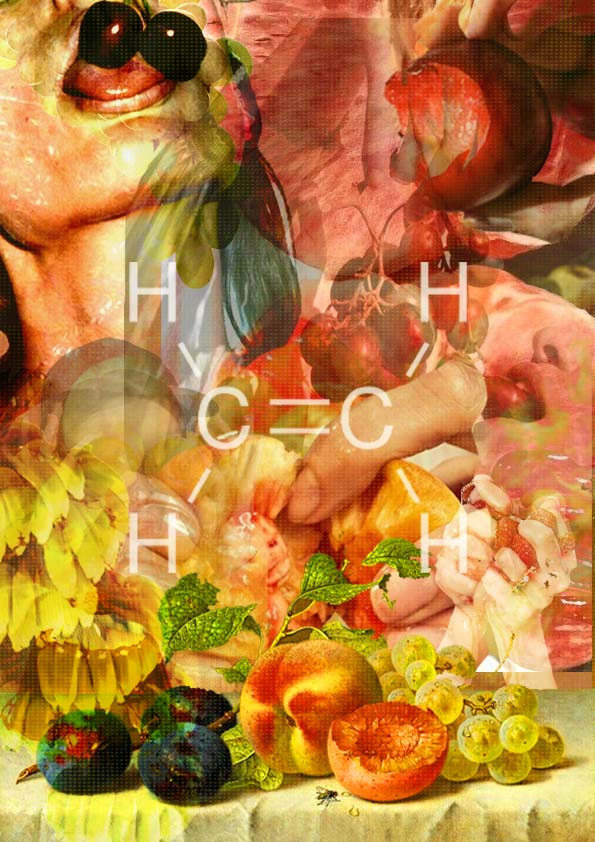

The process of turning sugarcane into PLA plastic is lengthy and complex. First, the sugarcane, or any other starch product such as corn, tapioca, cassava or sugar beet, is converted into sugar through the process of wet milling, where the starch is separated from the fibers and acid is added to keep them apart. The mixture is heated in order to convert the starch into dextrose (granular sugar). After wet milling, Lactobacillus bacteria is added to the dextrose which ferments it into lactic acid. This lactic acid is converted, through the magic of manufacturing and chemical manipulation, into lactide, a different chemical state of lactic acid which can, due to its molecular shape, bond into polymers. This polymerization forms small pieces of polylactic acid which can then be shaped into sheets, blocks and 3-D printing filament.

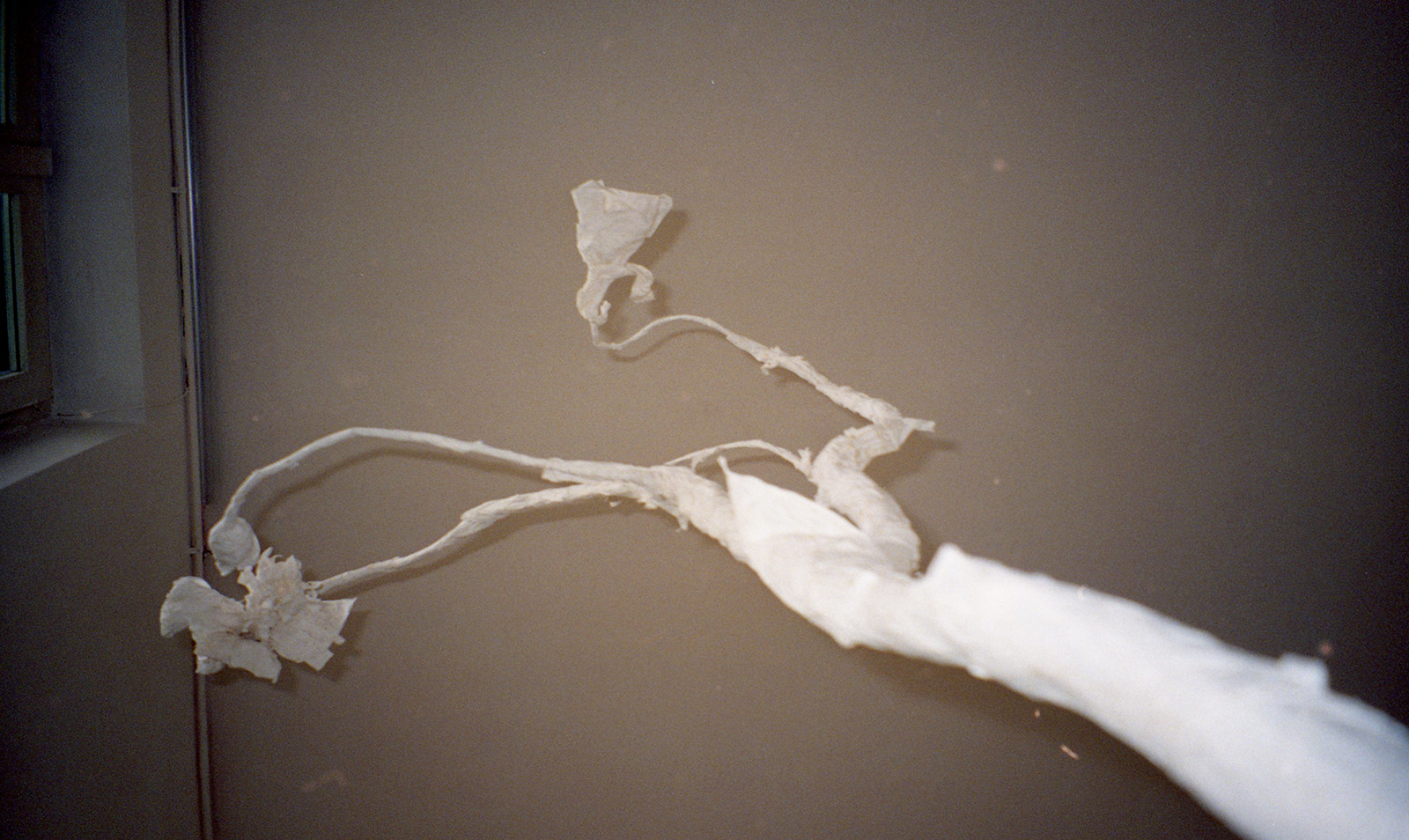

This filament was used by Mamou-Mani to print the modules of Aurora, which were then crushed and reprinted on site. The purpose of this process went beyond aesthetics and sought to question the concept of waste as something that has an end which is marked when the object is deemed useless. While the material itself could be endlessly recycled without aesthetic compromise, the installation was also designed in the same vein. Held together with thin metal rods, the modules could be easily disassembled, reassembled or repurposed as screens or chandeliers. Visitors were granted insight into this process as a 3D printer and plastic crusher on the mezzanine level of the museum crushed, melted and reformed the sugar plastic into the pieces that elegantly gleamed in the atrium light before them.

While less toxic and invasive for our natural environment than petroleum derived ABS plastic, sugarcane PLA plastic brings its own baggage. More brittle than ABS and with a lower threshold for heat, PLA can hardly be used for practical purposes and remains largely a decorative and experimental material. If magically it became a viable alternative to petroleum derived plastic, the amount of agricultural land and resources needed to sustain such a demand would devastate our ecosystems1. Sugarcane is a water-intensive crop that is aggressively grown due to its high demand which in turn escalates water scarcity in its farming regions. The crop’s demand also pushes farmers to neglect crop rotation thus quenching the earth of the nutrients needed to grow food and sustain life. This is leading to the rapid desertification of land across the globe, particularly in warmer climates and developing countries.

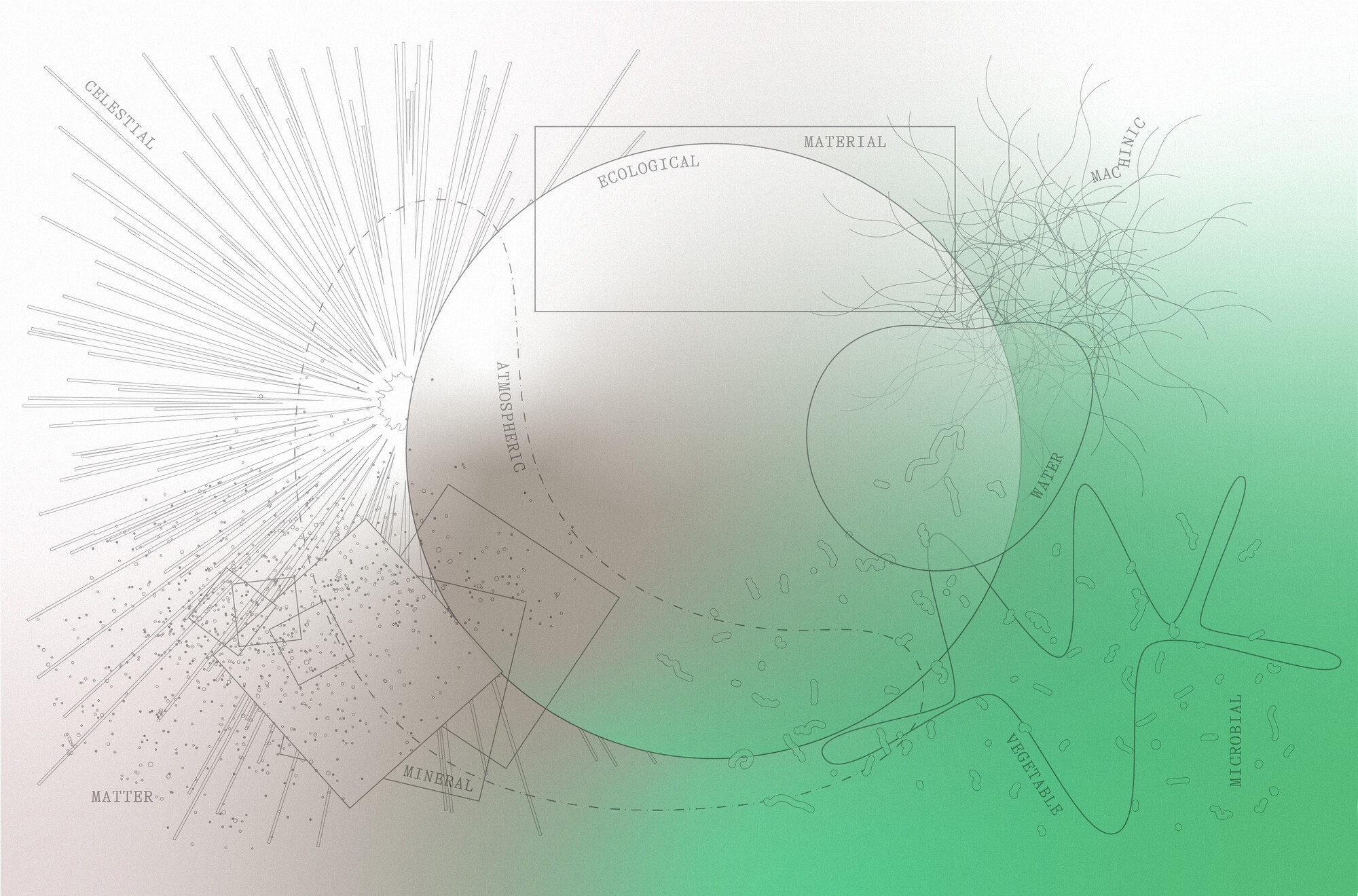

In the advent of additive manufacturing, sugar derived plastics played an important role in understanding the limitations and benefits of material while expanding our horizons to circular design and manufacturing. Mamou-Mani and his firm continue to center circular design and reusable material as the ethos of their design work, yet working solely in installation grants them this unique privilege. While Aurora’s awe striking beauty and success at the Design Museum’s Waste Age exhibition serves as hope and inspiration for a world where our relationship with material is more cyclical, organic and responsive, the real life applications of such insight have yet to occupy the realm of everyday living and the copious waste which accompanies it.