Upon return from the 60th Venice Biennale, the art world’s most prestigious exhibition, the biggest learning I walked away with is: Countries are an imposition. In many of the 88 national pavilions this year, the lesson was in a reclamation of history with marginalized voices centered. Feigning modernity, countries seek to compete in the global marketplace, extract their natural resources to engage as industrialized nations, and use the timeold ideology of progress to inspire their people. Those who govern, who hold the wealth, decide what is beauty and just. This year’s Biennale urges us— the viewers and visitors— to break from the notions of nation-states, cultural constructs, and appreciate the indigenous energies and natural world forever at play as the nexus and nucleus of so many world cultures.

In contrast to the national pavillions, this year’s anchor exhibition, Foreigners Everywhere – Stranieri Ovunque, curated by Adriano Pedrosa from Brazil makes good on its promise to focus on “the foreign, the distant, the outsider, the Queer, and the Indigenous.” Pedroso is the first South American curator and the first openly queer curator in the history of the Biennale. He delivers an uncanny beauty through 331 artists and collectives showing at the main exhibition.

People who normally write about the Biennale and critique it are usually from the white global majority. As a person who identifies outside of that majority, it’s important to declare that there remains power in speaking truths and being witness to indigenous artists, artists of a diaspora, artists who come from colonized spaces expressing themselves through diverse materiality. I am in awe of seeing so many iterations of firsts: Jeffery Gibson, the first indigenous artist to represent the US pavilion, the first time the Nordic pavilion features Nordic artists of East Asian heritage, Sandra Gamarra Heshiki, the first migrant artist chosen to represent Spain, etc., etc. For artists to survive generations of oppression, to be excluded from traditional spaces of art and still find the creative catalysts to share their expressions with the world, that is reclamation.

-Pietrangelo Buttafuoco, president of the Venice Biennale.“This Biennale Arte, then, hosts samples of marginalised, excluded, oppressed beauty, erased by the dominant matrices of geo-thinking.”

Below are a small offering of “national” pavilions to visit if you find yourself making the pilgrimage to Venice and if you don’t travel, please do read on about the infinite ways that these artists are working to reclaim their histories. National identities are a form of fiction we write ourselves into. Ask Lap-See Lam, a Swedish-born artist of Hong Kong Cantonese descent who is representing the Nordic Pavilion with her Altersea Opera. She told The Guardian that she was describing the idea of a Swedish identity and culture as a “fiction”. “In Sweden, we have this self-image of what Scandinavian culture is. And that has to be constantly reshaped.”

We exist in multitudes and because of colonization, migrations, and diasporas, the varied manifestations of expression are vast and sublime. It is a true honor to behold so many artists grappling with the complexity of identity, cosmology, and homelands. These artists are pressing on and have created a visual language for rectification.

The space in which to place me, Jeffrey Gibson

The Three Sisters

A member of the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians and of Cherokee descent, Gibson grew up in the United States, Germany, and Korea. His interdisciplinary practice and hybrid visual language combines American, Indigenous, and Queer histories with bold colors, patterns, and text. As the first indigenous artist to represent the United States, Gibson chose to bring in an additional 160 indigenous artists and leaders to Venice, embodying Gibson’s radically inclusive vision. On opening day, an indigenous elder blessed the pavilion by giving thanks to the grandmother moon, mother earth, and the three sisters of corn, beans, and squash—plants that sustain livelihood in the Americas. Gibson then transformed the forecourt into a living and breathing display of ceremonial dances and songs performed by Colorado Inter-Tribal Dancers and Oklahoma Fancy Dancers on top of a large-scale sculpture painted bright red. The installation offers a site for celebration and gathering.

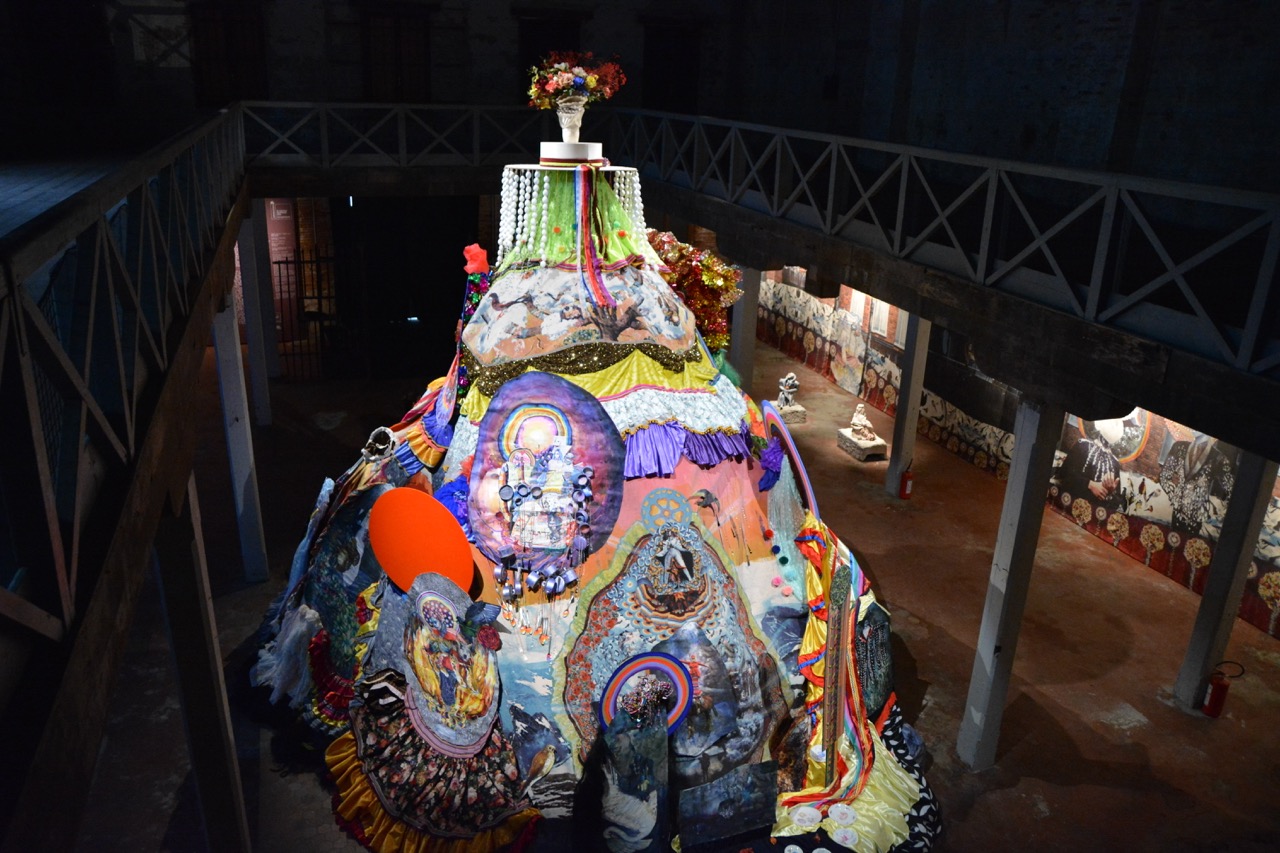

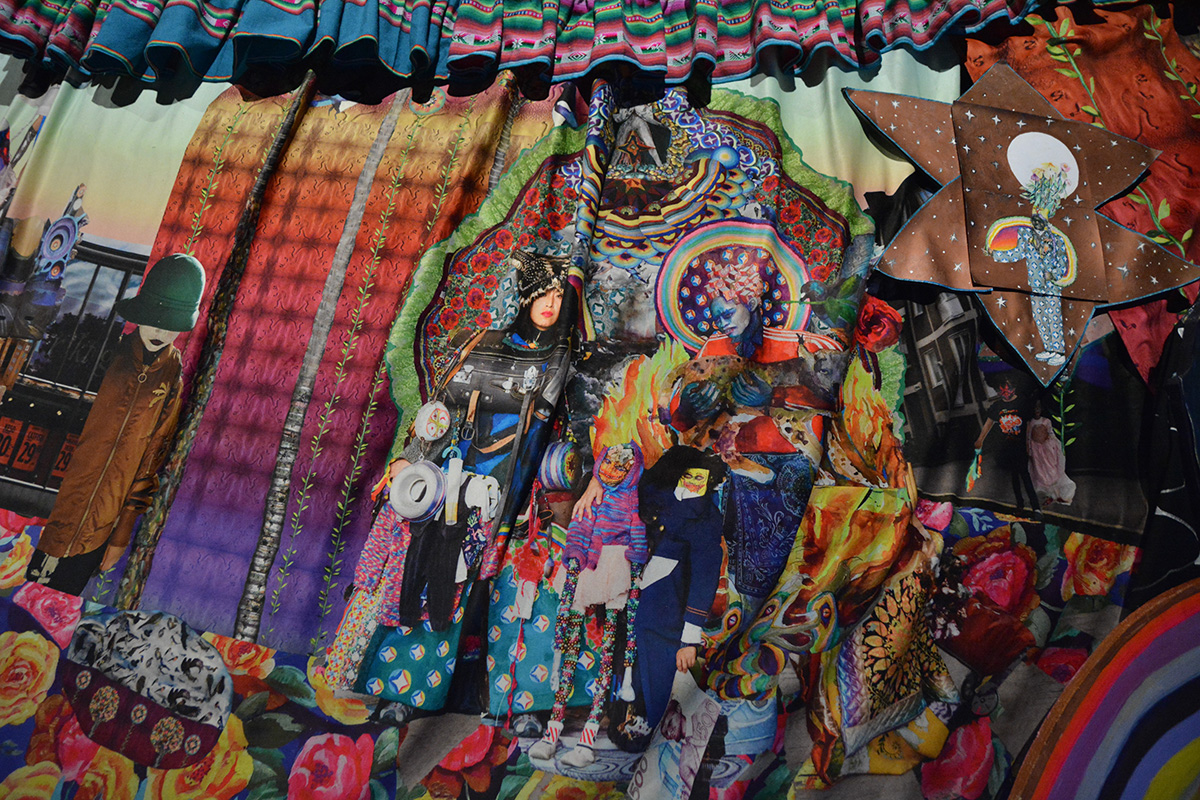

Cosmonación, Valeria Montti Colque

Mother Mountain

Artist Valeria Montti Colque erected a 16-foot sculpture titled “Mamita Montaña (Mother Mountain)” is constructed of carpets, textiles, photographs and ceramic pieces. Colque’s sculpture yearns to show how a mountain can be a place of ritual and political space. Colque was born in Stockholm into a family that was exiled during Chile’s military dictatorship in 1978. She named her exhibition Cosmonación to address the multi-site nature of nationhood that often encompasses geographically distant territories. Cosmonación was inspired by the anthropologist Michel S. Laguerre’s discussion of diasporic communities and their connections to their ancestral nations. Through nature and through memory, claims to homeland can be as powerful as those born on native soil.

Greenhouse, Mónica de Miranda, Sónia Vaz Borges and Vânia Gala

Creole Gardens

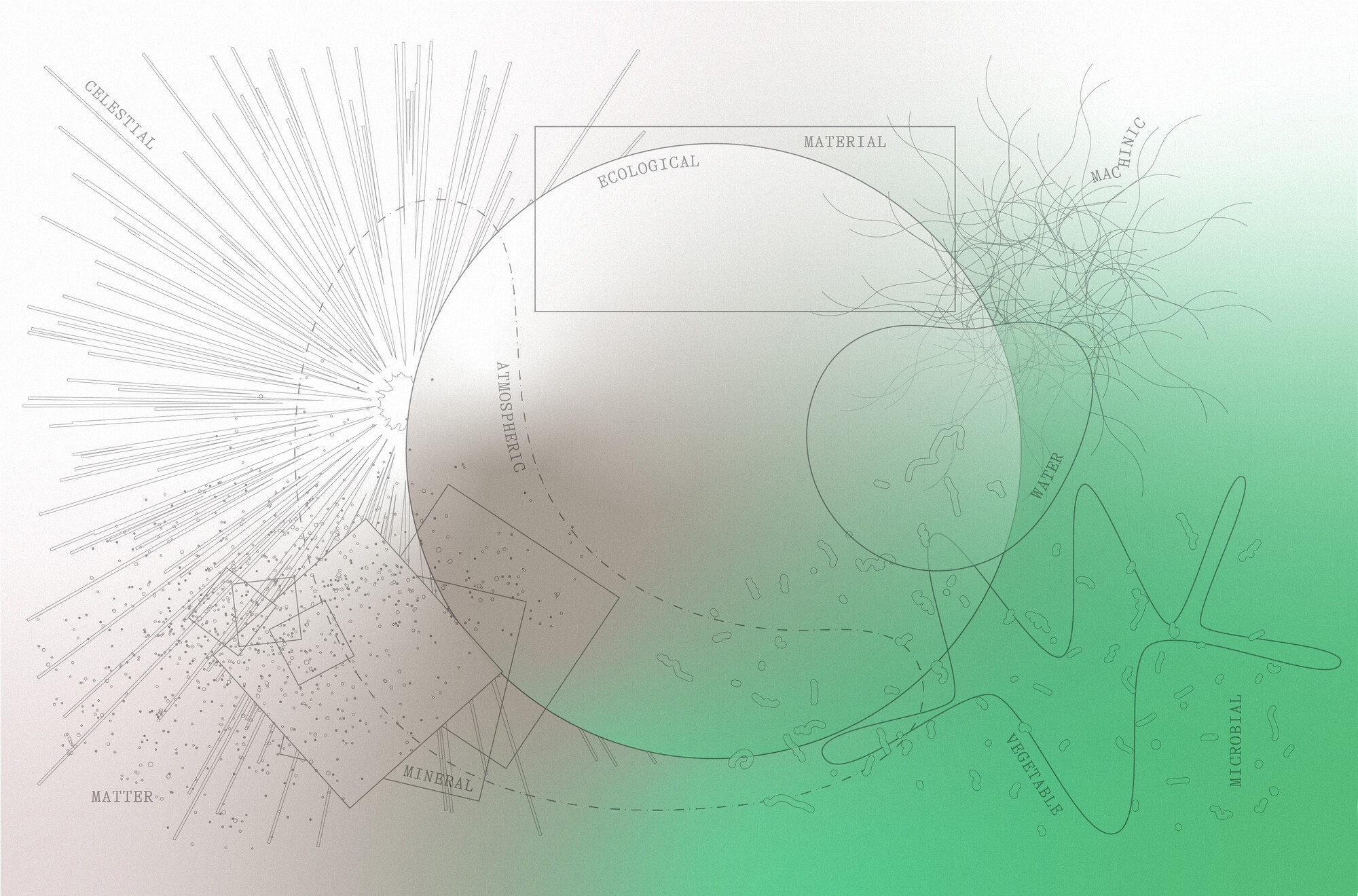

In Greenhouse, the Portugal Pavilion presented by artist-curators Mónica de Miranda, Sónia Vaz Borges and Vânia Gala, the garden becomes a space for grounding. Planted inside Palazzo Franchetti, a Creole garden illuminates the importance of a multi-strata agroforestry. The soil is an essential element that carries the memory of violence and stories of resistance and difference. Greenhouse insists that the regeneration of land is inseparable from the struggle for liberation, an idea seeded by the anticolonial organizer Amílcar Cabral’s in the fieldwork titled, “The Problem of Soil Erosion” from 1951. In this garden, there are moments of self discovery and collective care as the artists develop an ecosystem for action through gardening workshops for the local community, performance, and sound installations.

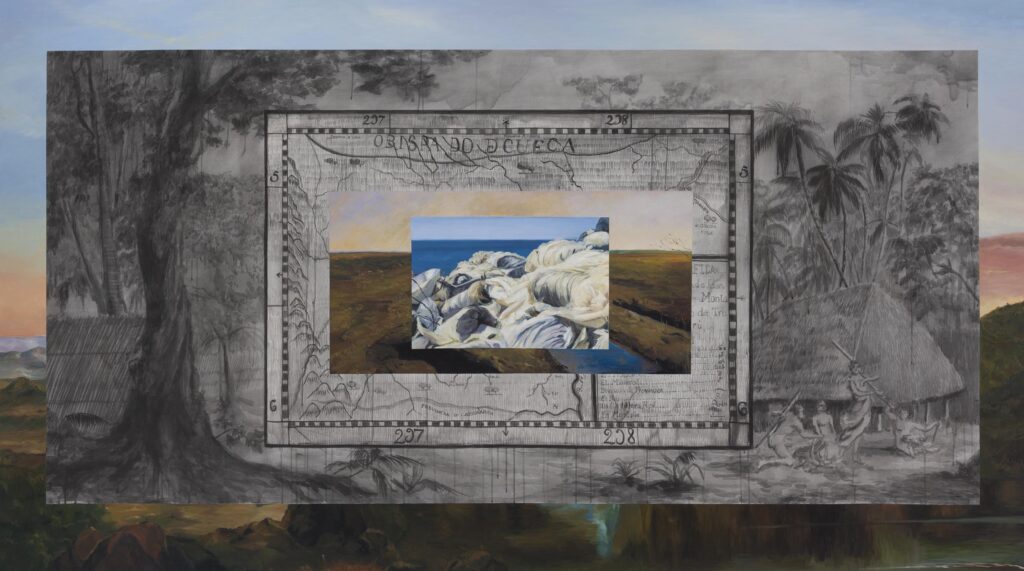

Migrant Art Gallery, Sandra Gamarra Heshiki

Invasive Plants

Within Peruvian-born artist Sandra Gamarra Heshiki’s Spanish Pavilion, she binds themes of colonialism to extractivism. What is most wondrous, is the artist’s ability to tie notions of migration to the natural world. We see prints and paintings with motifs of alien and invasive plants. The room titled “Cabinet of Extinction” displays the “treasures” of European botanical expeditions through the Americas during the 18th and 19th centuries. The painted facsimiles of the illustrations include human hands to show the same interdependent survival system for humans and plants. In the room “Migrant Garden”, twelve monuments symbolize Spain’s New World colonies as alien plants. Gamarra Heshiki insists that these migrants have found soil to survive and stay and that all species have the right to to live harmoniously without hierarchies.

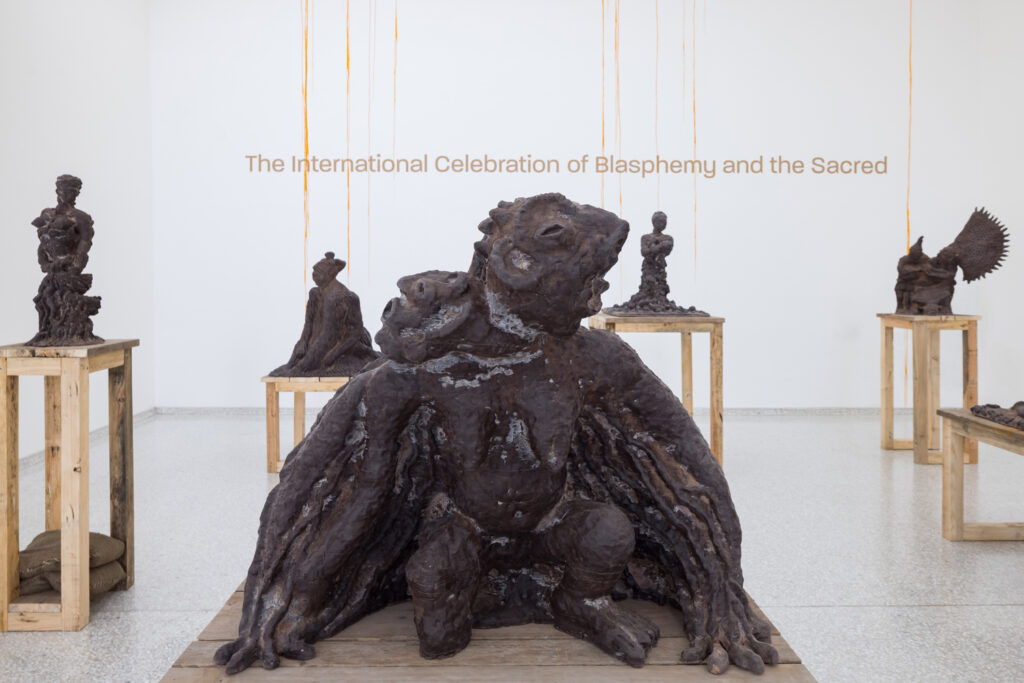

The International Celebration of Blasphemy and the Sacred, Cercle d”Art des Travailleurs de Plantation Congolaise

Regenerative Forests

The sweet smell of cacao permeates the angular and stark Dutch Pavilion. The gallery is filled with sculptures made of clay from old-growth forests then recast in cacao and palm oil with titles such as “Forced Love”, “Forced Labor”, “Plantation Master” by the Congolese artist collective Cercle d”Art des Travailleurs de Plantation Congolaise (CATPC) . Since 2014, CATPC has been working to purchase ancestral lands back from the Unilever corporation. Their vision is to regenerate sacred forests and establish a sustainable economy that would allow them to thrive, post plantation. They say by selling their artwork abroad, “Each sculpture will mark the passage from a painful and dark past to an ecological tomorrow…” Their broader mission as artists is to bring spiritual, ethical, and economic reckoning.

Listening All Night To The Rain, John Akomfrah

Sounds from Nature

You could dedicate an entire day to John Akomfrah’s BritishPavilion, channeling post-colonialism, environmental devastation, and the politics of aesthetics through video narratives. The feeling is a sublime attraction to the eight color-coded rooms named “cantos” that fill with voices, soundscapes, and video montages as ‘memories’ of migrant communities in Britain. We watch multiscreen geopolitical narratives reflected in the words of diasporic people across an English countryside. By layering audio materials of political speeches and sounds from nature, Akomfrah intersects perception and discourse through sound. One canto is dedicated to the legacy of the conservationist Rachel Carson whose work established the modern environmental movement. Akomfrah writes of the exhibit, “the architectonics of the present and the spectres of the past, with the idea of listening as activism in mind.”

The Altersea Opera, Lap-See Lam, Kholod Hawash, and Tze Yeung Ho

Half-Sea, Half-Land Mythology

A giant Cantonese dragon head greets you as you enter The Nordic Countries Pavilion, giving you the sense of sea going grandeur and adventure. Like a siren song, the sound of a layered libretto audio-visual installation pulls you into the building. Conceived by Lap-See Lam, a Swedish-born artist of Hong Kong Cantonese descent, The Altersea Opera explores alienation and displacement as well as conflicting feelings on the imposition of national identity. Lam worked with Finnish artist Kholod Hawash and Norwegian composer Tze Yeung Ho collaboratively to present the experimental musical installation and performance inspired by Cantonese Opera. It is the first time the pavilion features Nordic artists of East Asian heritage. Upon leaving the half-sea, half-land mythology of living in-betweens, you are left with a feeling of beauty that comes from the collective song.