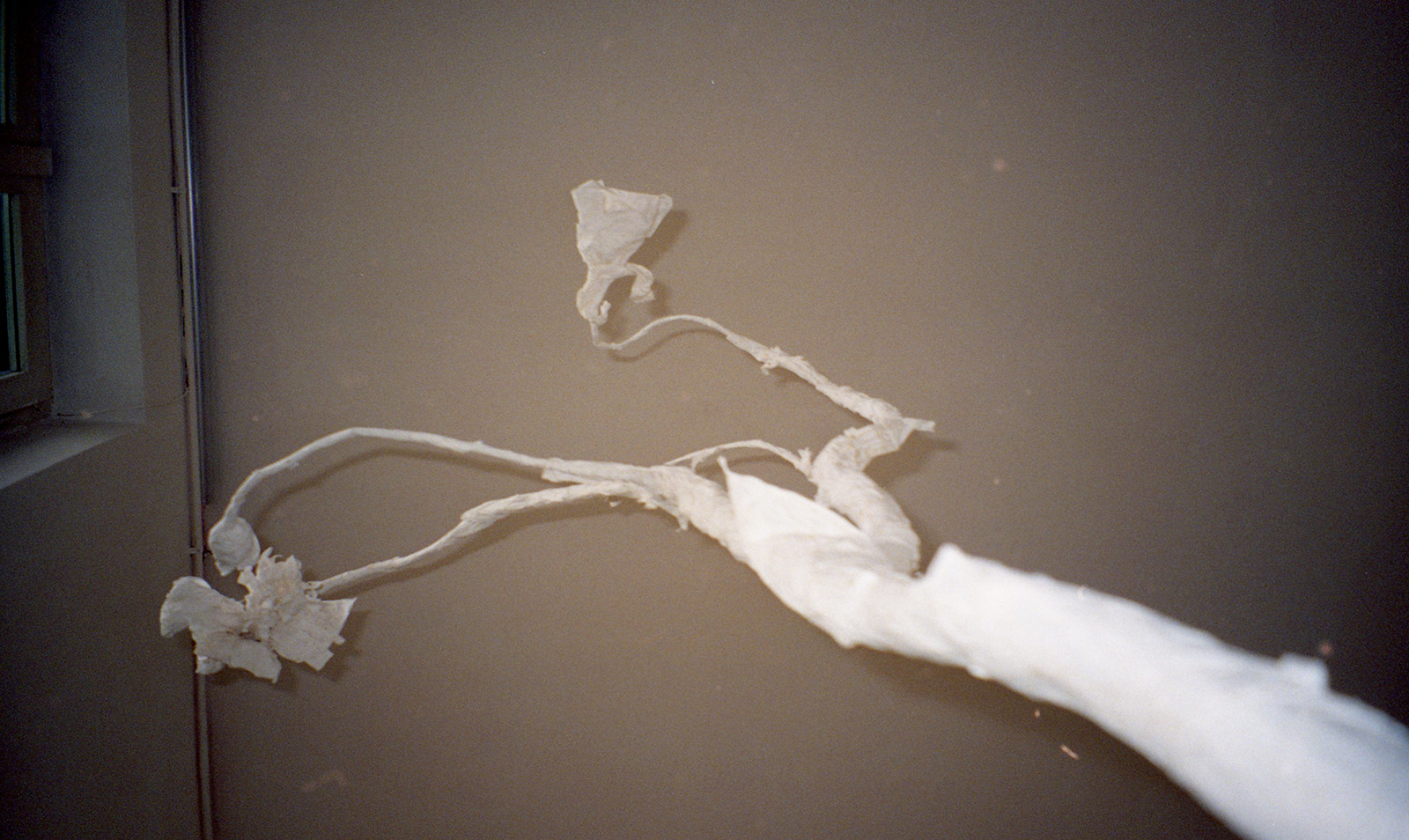

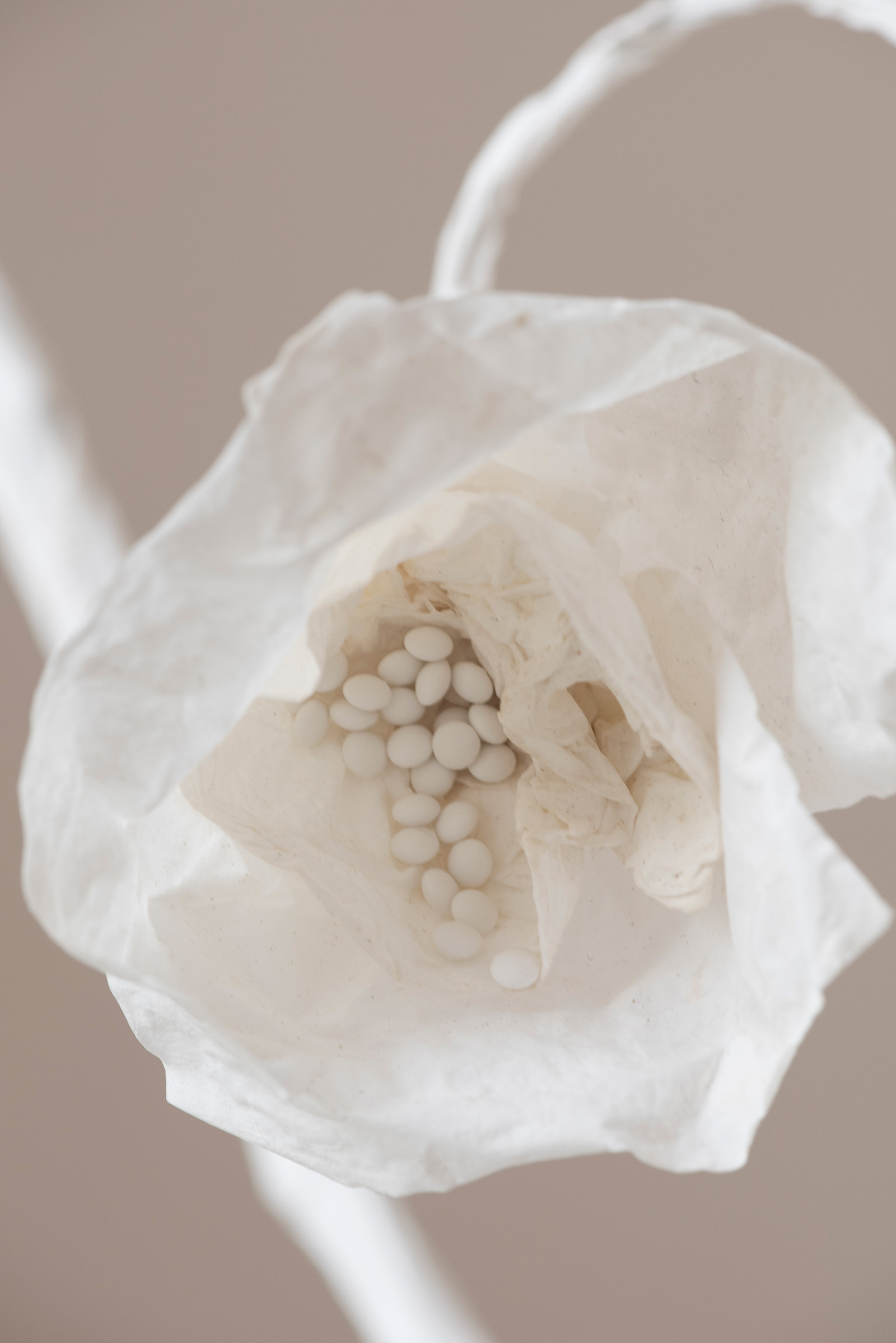

Extract from Agerskov’s text, Silphiofera, speculating on the return of an ancient extinct flower.“Yesterday, someone saw the flower appear again after its deep millennial hibernation. At a dewy dawn, it was seen between the birch trees on a hilly area. Only that, this time, the flower was made of paper and flour. A dried-up, forgotten bread crumb, its skin translucent when the morning light caught its back.”

Alberte Agerskov’s practice has a particular quality, which allows her to dialogue with the poetic potential of reality and complicate it in order to extract the uncanniness of existence; a primitive conflict that is, to use Andrea Fraser’s words, “central to every person, and every social structure”[1]. This is felt in Agerskov’s Silphiofera, where we meet two intra-laced empty flower fields, installed on separate levels of the exhibition space. Upstairs, the floor morphs into a humid, off-white landscape impregnated with paper and flour, feeding us a powerful sensorial experience the moment we remove our shoes to walk it. Out of the translucent meadow, an oneiric, flower-shaped sculpture grows and evokes images of femininity. Yet symbolic connotations are complexified the moment we notice that the seeds sprouting from the plant are contraceptive pills.

- 1. Buhmann, Stephanie, Los Angeles Studio Conversations, Sixteen Women Talk About Art, p.26, published by The Green Box.

We then find ourselves floating in a liminal space where sight, smell, sound and touch not only constitute the reality of our lived experience but also become portals to other existences, ultimately interlacing us with them. As we inhale the pungent smell of flour amalgamation, and hear the womens’ voices that compose the rhizomatic sound piece of the ground floor courtyard, we somehow nourish ourselves with and simultaneously become bodies for these existences to grow. We become recipients[2] – wombs for them to be born again. Nutrition and expulsion, just as control and freedom, lie at the core of Silphiofera, positioning the project metaphorically and physically within the lineage of the new material feminist discourse.

- 2. Le Guin, Ursula K., The Carrier bag Theory of fiction, 1986

“The flower’s roots went deep down underground, hitting the water that rivers and people and clouds and birds and everything else had been ingesting and urinating and raining and weeping and swallowing and sweating. The rebirthed flower drak and drank and grew taller and taller.”

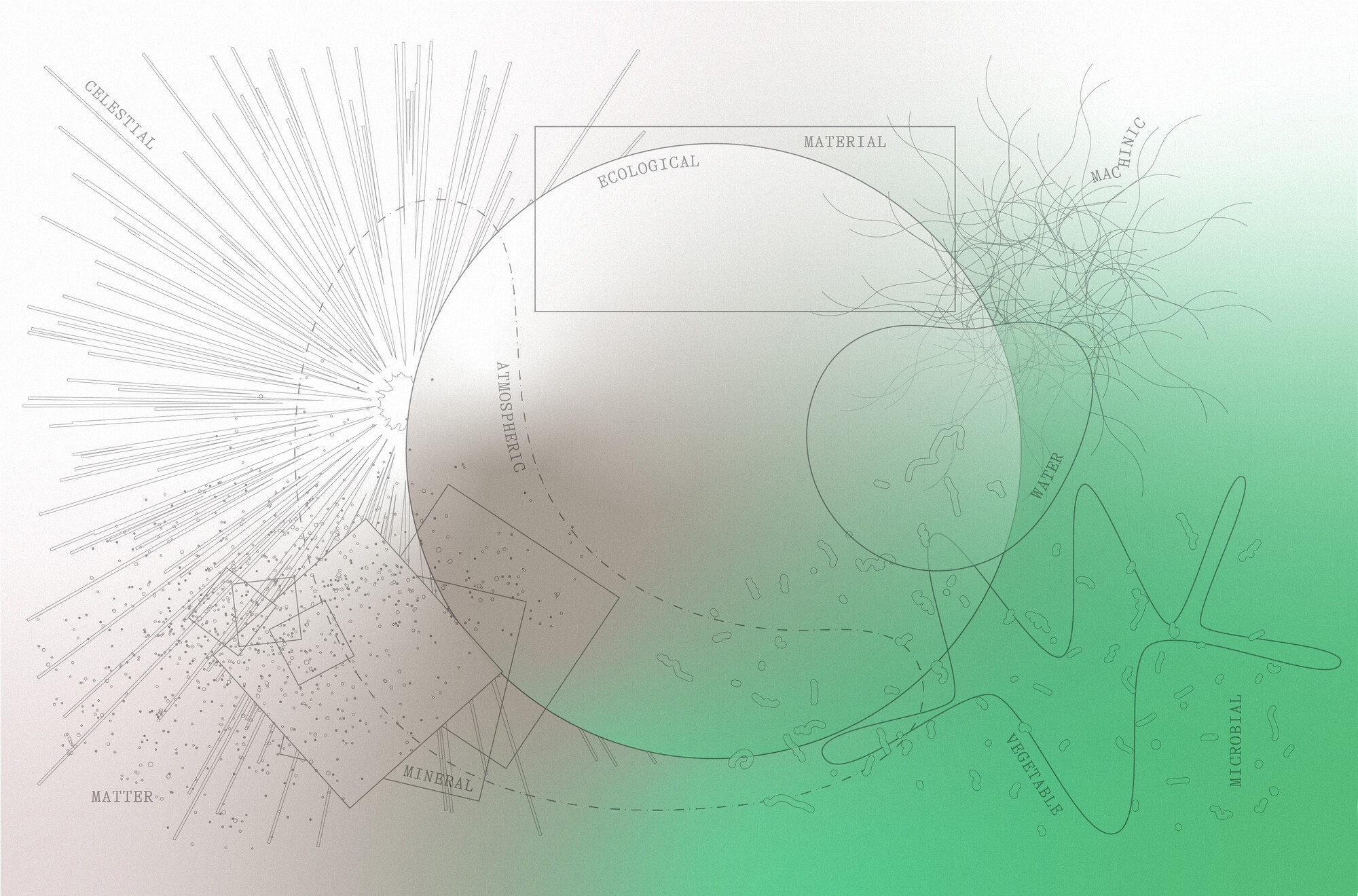

We are all part of a planetary hydro-common[3] system, where the water that we are composed of viscerally links our human bodies to other earth bodies: oceans, plants and animals. We all flow within the same cycle where our urine is not different from the water raining on the land, and the milk generated within our breasts is nutrition for infants and plants alike, as poetically described through the story of Mahdokht in Shahrnush Parsipur’s Women Without Men. Here, a woman who decides to plant herself in the earth as a tree is fed with the breast milk of the gardener’s wife until mid-spring, when her body explodes and the tree turns into seeds that blow into the water. This image, drawn from a controversial piece of Iranian literature, creates an assonance with the horticultural practice of milking used to extract bioactive molecules from the roots of living plants, and conceptually borrows from the biological process of breastfeeding where nutrition and extraction are codependent.

- 3. Neimanis, Astrida. Bodies of water: Posthuman feminist phenomenology. Bloomsbury Academic, 2017.

Indeed, milking is the ancient technique that was used to harvest the Silphium plant’s medical juices, reported to have contraceptive properties. Due to human overexploitation, it was the first plant recorded to become extinct, which calls attention to the ambivalence of the techno-optimization of natural processes, and brings to light the controversial intra-space between a promise of freedom and an invisible imposition of control. These powers are subtly entangled, and the shift from one to the other occurs when caring about something transmutes into being concerned about it. As stated by Maria Puig de Bellacasa, “…concern and care have acquainted meanings – both come from the Latin cura, “cure.” ”[4]. But they also express different qualities and to care about the body results in the raving control of it when patriarchal structures become concerned with its meanings, (in)efficiencies and other-agencies. Therefore, although the choice of using contraceptives offers the potential for reproductive emancipation, it also denies the body of its autonomy; in the same way, the technological deconstruction of a maternal process may open up the possibility of choice, but yet it fuels the commodification[5] of human biologicals, ultimately leading to dis-embodiment.

- 4. Puig de la Bellacasa, María (2017) Matters of care: speculative ethics in more than human worlds, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- 5. Lock, M. and V.-K. Nguyen, 2010 An Anthropology of Biomedicine. Malden, MA: John Wiley & Sons.

Agerskov does not question the right to choose. Instead, she enables an unraveling of meanings, hierarchies and cleavages that grow, when the body and the agency of its fluids are appropriated by technology. It is about lingering in limbo, where ambivalence resides and contradictions occur. Within this space, one may well wonder why the global average time for maternity leave is 14 weeks, when breast milk production can last up to two years with the highest production occurring in the first six months. Right here, the intra-space unfolds and reveals how the body’s natural process is relegated to a realm of dysfunction when confronted with socially constructed norms. In a capitalist system where women must rely on infallible technology (e.g. breast pumping machines) to fit the socio-political agenda, lactation stops being a process and becomes a product. Not flowing within and through the body, but pumped out of it, just like the knowledge that women embody and the practices resulting from it. Indeed, this set of practices, borne by the hands of experts and educators, reformulate breastfeeding as something that can only be learned through culturally institutionalized instruction, potentially leading to an increasing separation between mothers and the value of their bodily experience.

“Caring and relating share ontological resonance”[6], so what happens when we stop relating to other bodies, when a mother stops relating to an infant, and we are increasingly drawn to relating to substitutive, technological bodies? What happens when our fluids and flushes and watery existence are regulated by visible and invisible technologies? Through control, we can suddenly opt for freedom. Freedom from the pain of menstrual cycles and mood swings, freedom from the fear of our bodies lacking efficiency, freedom from presence when we can remotely be everywhere, freedom from doing when we can just have things done, freedom from memory when we can buy enough i-storage. Is this freedom at all?

- 6.Puig de la Bellacasa, María (2017) Matters of care: speculative ethics in more than human worlds, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

To assume control of ourselves is a means of empowerment, yet we might want to take into account how this condition changes when negotiated with the complexly ambivalent system of agencies we live in.