Stepping into SOIL: The World at Our Feet certainly feels like you’ve entered the subterranean. Located in Somerset House’s basement gallery, the hall’s cool quiet offers a contrast to the harsh din of London’s Embankment, thronged by HGVs and idling cars. The exhibition, on view until April 13th, 2025, explores the manifold worlds contained in soil and its role in sustaining life on earth.

Soil in art isn’t new. Some of our earliest examples of art, cave paintings, involved soil as a medium. Entering the exhibition, I am admittedly skeptical. In recent years, soil and earth-based works have understandably seized the art world as climate change has turned our attention toward the planet. However, these artworks and exhibitions have often fallen flat, by isolating these concepts in climate-controlled white cubes, the potent livingness of this subject matter is often lost without a broader ecosystemic context. At SOIL, the copywriter’s flavoursome use of earthen idioms—a ‘groundbreaking exhibition,’ ‘unearthing soil’s vital role’—which somewhat contradicts a healthy soil’s modus operandi; leave me expecting a show which scratches the surface, but might not dig much deeper.

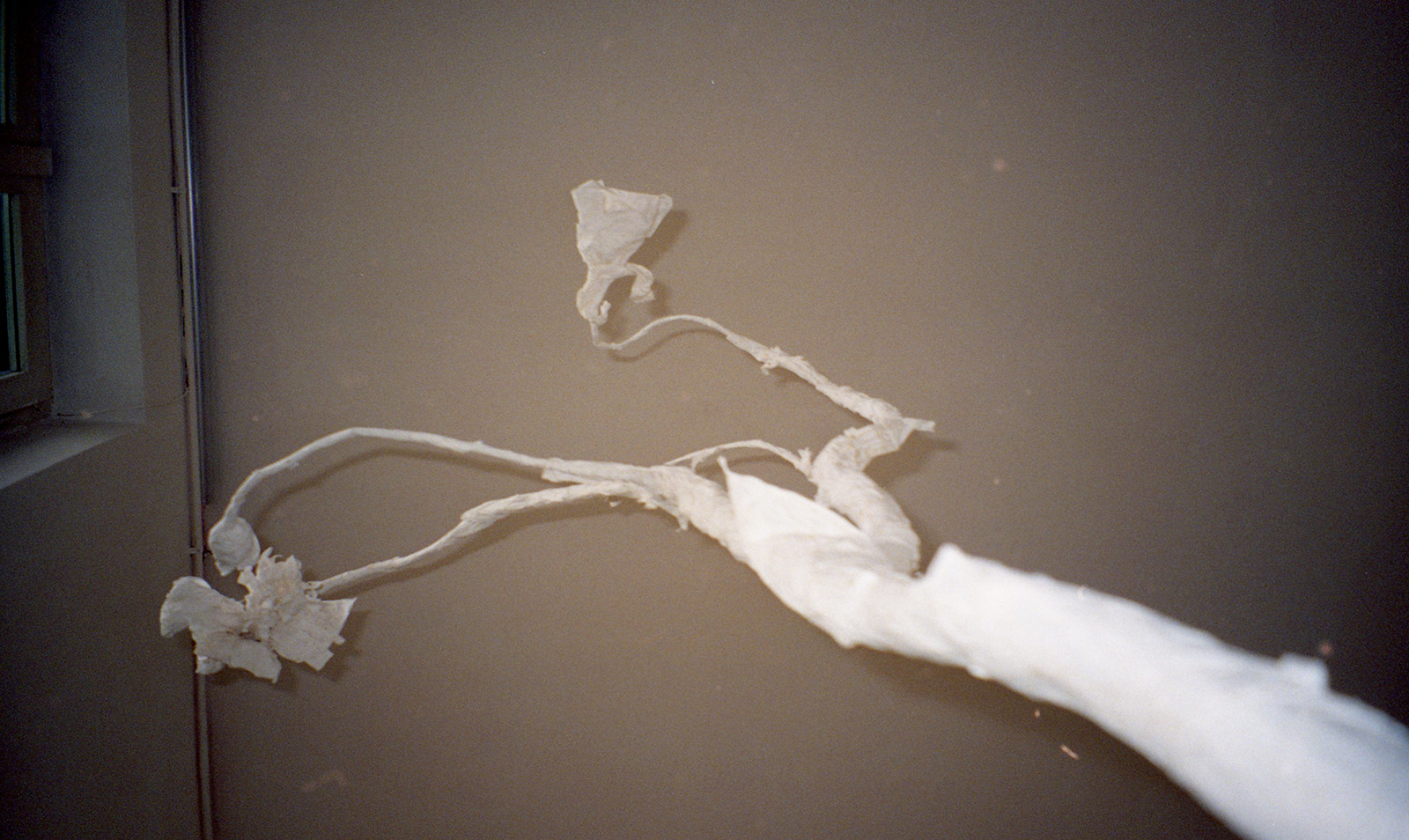

The entrance to SOIL is announced by what appears to be cracked vinyl which, upon closer inspection, reveals itself to be literal soil applied to glass. Crafted by bioengineer Christopher Bellamy, this ‘Soil Sign’ is sourced locally and can be recycled back into the ground after the show is done. From the entrance, brown, textured walls curve away into a low-lit passage, from which echoes the otherworldly sounds of munching and mulching.

In this underground world, the first artworks one sees zoom down to a microscopic scale, typically unseen by humans. In a large alcove, Jo Pearl’s collection of hanging ceramic microbes titled Oddkin (2024) sway in an unfelt breeze. Drawing their name from Donna Harraway’s book Staying With The Trouble (2016), Pearl’s Oddkin are recreations of the unusual species with whom we unwittingly collaborate in our existence on earth, highlighting the interspecies connectedness of soil.

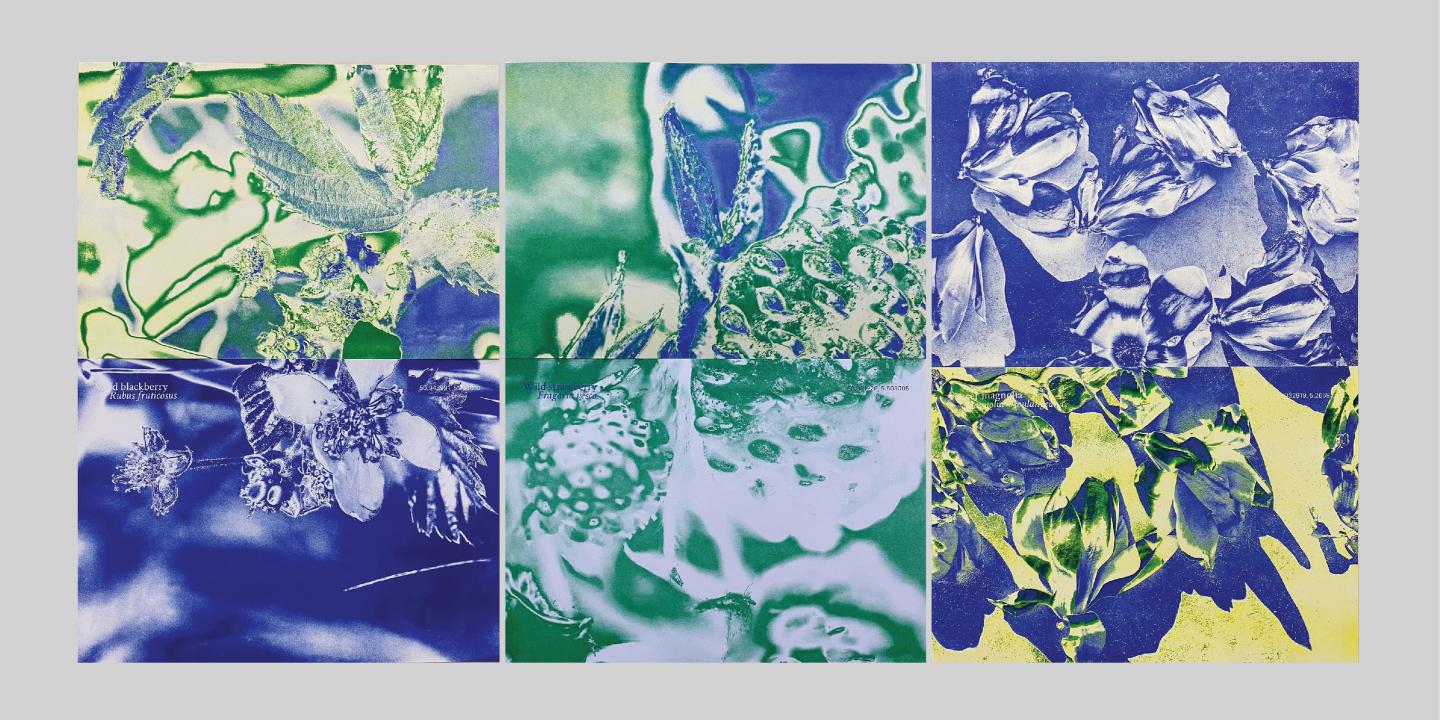

Across the room, Daro Montag’s photo series This Earth (2006) shows blown-up images of microbial activity. Building on this narrative of interconnectedness, Montag’s images are the result of photographic paper being exposed to microbes, with whom he collaborates to create these vividly colourful images of interspecies abstraction.

From this first room, one emerges into Wim van Emgond’s Mating and egg laying earthworms (2021), whence the munching and mulching comes. The work consists of a time-lapse projected large across hanging curtains, portraying myriad plant, animal, and fungal species moving in and around one another in an endless choreography. In an adjacent room, Marshmallow Lazer Feast’s Fly Agaric 1 – Poetics of Soil (2024) plays a CGI fungal fever dream to the narration of mycologist Merlin Sheldrake.

Like in the first room, these video pieces continue to play with perspective. Standing there, the viewer is placed at the viewpoint of an insect, or small plant looking up at the world from ground-level. Looking up at the underside of a vast mushroom releasing its spores, or the giant footage of sprouting seeds at high-speed, one begins to get a sense of the complexity of these tiny worlds.

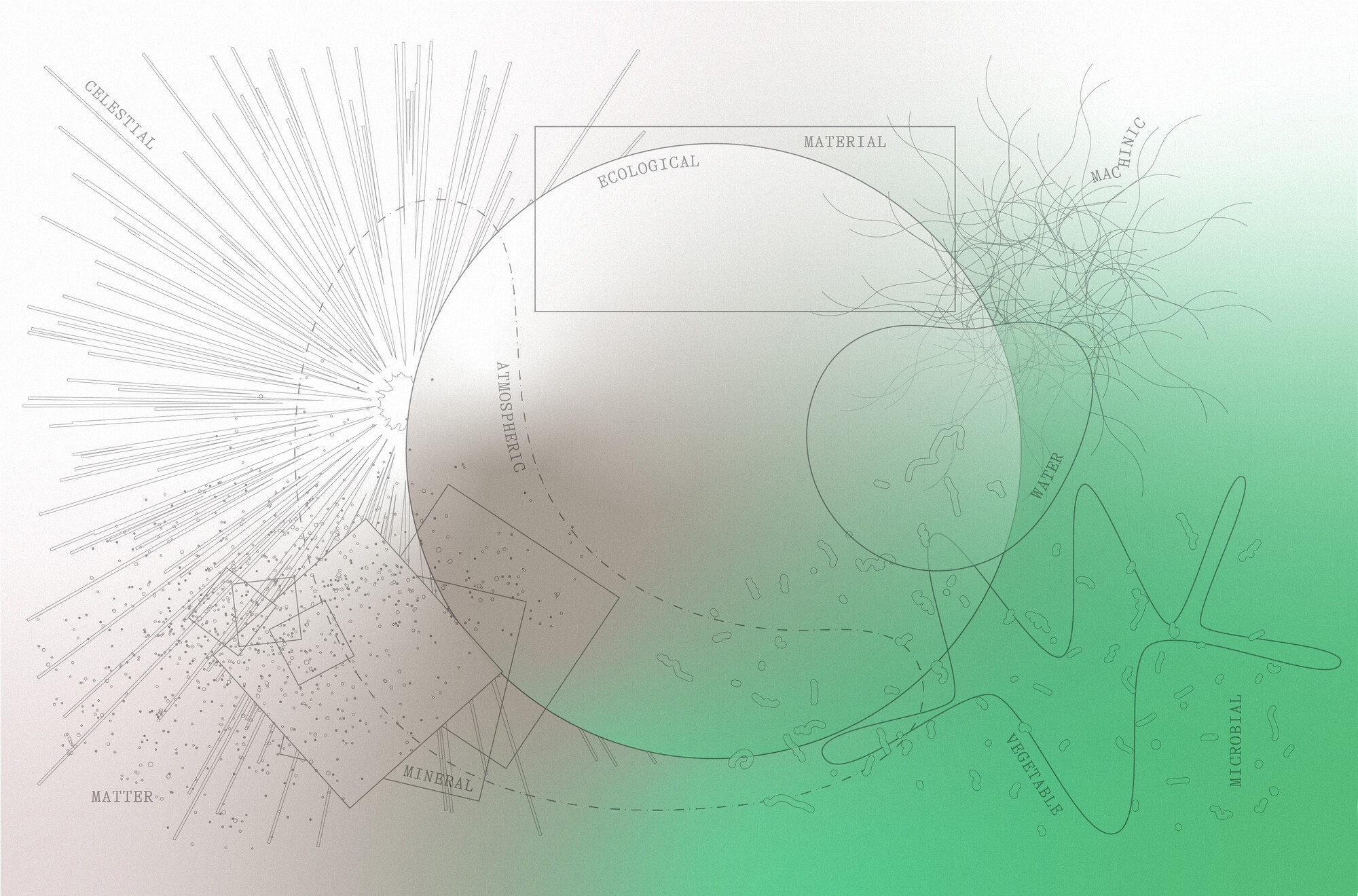

At this juncture, it becomes clear that the exhibition is curatorially structured around scale. These transitional pieces in the second room document organisms which bridge both under- and above-ground worlds. Climbing up into the brightly-lit macro surface world of the mezzanine, the artwork shifts to human scales in a resplendent frenzy of different artistic interpretations of soil.

herman de vries’ from earth: kreta (1992) displays 48 samples of Cretan soil rubbed onto paper. This collection forms part of a 9,000-strong archive collected over the course of 50 years by herman, which form the earth museum housed in Musée Gassendi in Southern France. herman emphasises that his ongoing collection of rubbings aren’t intended as scientific tests, but rather to make visible the brilliance of soil’s colour in an aesthetic appreciation of its diversity.

In Julia Norton’s eponymously named film Julia Norton in her studio (2024), the artist explains the materiality of soil as a medium, and the importance of ochre as an earth pigment in her art practice. Norton’s broader practice considers how materials can function as collaborators, and the collective connections that can emerge when these collaborations become artworks.

Kim Norton’s Soil Library (2017-ongoing) takes the materiality of soil one step further in her archive, which seeks to document soil’s ceramic qualities. Sourced from across the UK and Europe, Norton mixes the soils she finds with porcelain to create simple pinch pots, which she fires, and then catalogues by location.

Further ahead, the warm smell of damp sawdust and yeasty ferment mixed with sharp overtones of citrus wafts over you. This is Fatima Alaiwat’s Smellscape: Rhythms with Bokashi (2022), an olfactory map exploring the different scents that rise from the bokashi; a concentrated fermentation process that breaks down organic matter into fertiliser. Alaiwat’s work is inspired by a Maria Puig de la Bellacasa quote, ‘What soil is thought to be, affects the ways in which we care for it, and vice versa, modes of care have effects in what soils become.’

Alaiwat’s reference to Puig de la Bellacasa highlights a common theme that runs between many of the exhibition’s works: the less tasteful side of soil’s human entanglement and its use as a resource. Soil, and the land it makes, intrinsically underwrite notions of ownership. From the creation of capitalism, enclosures, and clearances, to plantation, displacement and enslavement; soil has been a driving factor in much of the ugliness of the world we live in. Though the curatorial text alludes to this with ‘Soil is the receptacle of our history and witness to all our actions,’ the main message is left to the artworks to explore.

This complex relationship is runs deep in Theo Panagopoulos’ gentle film essay The Flowers Stand Silently, Witnessing (2024). Reworks found footage of Scottish settlers in Palestine during the 1930s and 1940s, Panagopoulos draws links between the displacement of people and the colonisation of their lands.

In another room, Vivien Sensour and Neville Wisdom’s film Ahl el Thara, People of the Soil (2024) examines similar subject matter, documenting people from around the world who share a reciprocal connection to soil, and extractivism’s threat to this. Most of the footage chronicles people who are part of the Palestine Heirloom Seed Library’s Seed Protectors Project, where Palestinian seeds are lovingly tended by volunteers in the United States to keep their heritage alive.

Cultures of extraction through agricultural systems are also highlighted in Annalee Davis’ Saccharum officinarum and Queen Anne’s Lace (2015), and Unlearn the Plantation (2022-23), which highlights soil’s connection to the capitalist machinery of the plantation, and the history of human enslavement and displacement this caused. Similarly, Asunción Molinos Gordo’s Ghost Agriculture (Unlimited Resource Farming) (2018) explores how Egyptian agriculture is shaped by the interests of big businesses and central government, to the detriment of local populations.

Individually, each of these pieces explores a unique story of the interconnection between people and the land. In their combination, they shed light on the ugly side of soil with care and gentleness, offering an understanding of the often violent and exploitative entanglement of people and land in considered and accessible ways.

This is underwritten by some of the other artworks on display, which centre the loving relationships humans can reciprocate with the soil. In her Growing Memories (2021), Johanna Tagada Hoffbeck uses oil paint to emphasise the slow relationship she has developed with soil, as taught to her by her grandfather. This inter-generational relationship highlights the care seen in Sensour and Wisdom’s Ahl el Thara, People of the Soil, amongst other pieces, and reminds the viewer that our relationship to the land need not be extrasctivist.

Upon leaving, my general perception is that in its attempts to capture the infinite complexity and diversity of soil, the exhibition largely succeeds. It feels chaotic, yet this is not criticism. Soil is chaos, for we cannot refine its entirety into our comprehension. Whether intentionally or not, this ultimately lends to the theme; an unbound messiness we might not ever understand. It is not some brown substrate, but innumerable intersections and entanglements, all thriving in their own way. Visitors should not expect to see soil from every perspective, but instead understand the infinity of perspectives it offers. If anything, SOIL: The World at Our Feet is a salient reminder that the world isn’t at our feet, we are, in fact, at its.