This piece is part I of a five-part series by Jen Monroe of Bad Taste and Caroline Maxwell of Wild Dogs International, ‘Balling the Queen: On Honey Bees, Consumption and Collapse.’ Focusing on the plight of pollinators and colony collapse, this series serves as a precursor to their event Balling the Queen: A Dinner Salon Exploring Honeybees, Consumption and Collapse.

Every year, right around Valentine’s Day, the California Central Valley bursts into a froth of pale pink and purple. 1.33 million acres of almond orchards bloom, stretching from Tehama County in the north through Yuba and San Joaquin and Fresno, all the way to Bakersfield. The state grows 80% of the world’s almonds, making it California’s most important crop and the epicenter of the American monoculture. It’s also unbelievably beautiful, yielding dramatic drone shots of the hills and valleys blanketed in pink that look more like screensavers than reality.

Crabtree Farm near Modesto Reservoir, CA. Photo by George Steinmetz for Bloomberg.

Crabtree Farm near Modesto Reservoir, CA. Photo by George Steinmetz for Bloomberg.

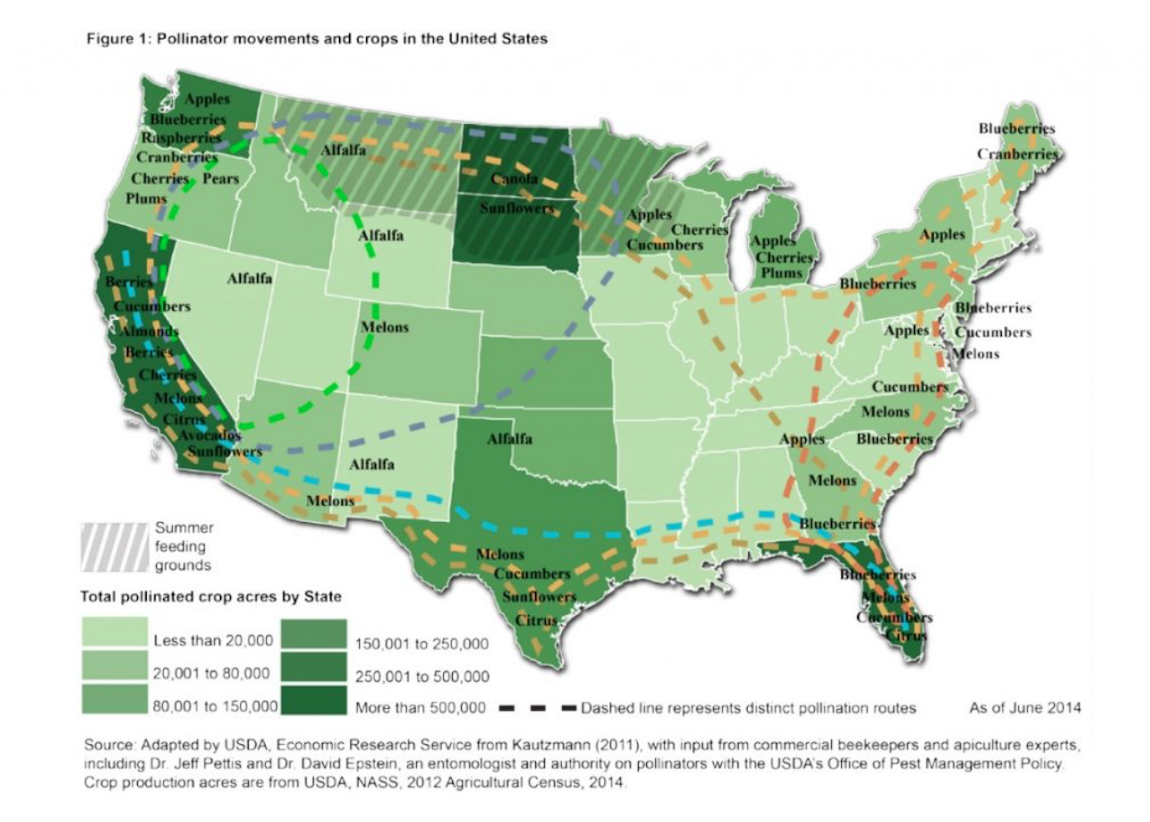

To ensure that the orchards bear fruit six months later, their flowers require pollination—but how do you pollinate such an enormous crop all at once? The answer: a lot of honey bees. Each year about 80% of the honey bees in America, or about two million hives, are packed onto semi trucks and shipped to California from all over the country. It’s the largest pollination event in the world, and it continues to grow as the demand for almonds increases, with farmers asking for an additional 200,000 hives each year. Commercial beekeepers struggling to maintain their honey bee populations are confronted with alarmingly high die-off rates each winter, so their pollination services are becoming increasingly expensive: while 20 years ago, farmers could expect to pay about $30 to rent the services of one honey bee hive, these days it’s around $200. For some almond farmers, pollination fees can account for about a quarter of their total overhead expenses—and yes, those fees are reflected in the price of groceries.

While we might use this as a tidy anecdote about supply and demand in the context of industrial agriculture, or as an example of how the soaring expense of pollination could conceivably make certain foods prohibitively expensive (especially in food insecure communities who may already have less access to fresh produce), the problems with pollination are about much more than money. California almonds have gotten a lot of bad press for their enormous water consumption—a gallon per nut, which is particularly destructive in the drought-prone Central Valley. However, their most pressing side effect isn’t water use but rather the necessity of mass-scale migratory beekeeping, the term given to commercial honey beekeepers who truck their hives (sometimes tens of thousands of them) around the country, following the blooms of different crops by season. But migratory beekeeping couldn’t exist without monocropping, and vice versa—and monocropping has had devastating effects on honey bees, native bees, and pollinators at large, owing to large scale elimination of habitat and biodiversity, synthesis of ideal conditions for pathogens, pests, and parasites, and its contamination of water sheds.

Like industrial agriculture itself, migratory beekeeping is a daisy chain of cascading failures, the solutions for which tend to yield further sets of problems. Our resultant food system is so fragile and contorted that, by design, it can’t continue indefinitely. (We’re so mired in questionable uses of the term “sustainability” that we’ve been desensitized to what the word implicitly means: that continuing down a path of unsustainability necessitates that our current methods of feeding ourselves will collapse; are finite.) At the center of this agricultural maelstrom are the honey bees, who are constantly besieged with their own rotation of health challenges. Over the past decade you’ve probably seen headlines about Colony Collapse Disorder, the impending extinction of the honey bee, and the subsequent food apocalypse towards which we seem to be headed. It’s been increasingly difficult to parse how much of this merits genuine concern, what is supported by credible science, what is still unclear, and what is speculation, especially as the understanding of honey bee health continues to shift so much in all directions. To put it bluntly, we are still very much experiencing a crisis of honey bee health, and the ramifications do warrant concern, but they may not be the same concerns that the headlines suggest are the most troubling.

* * *

Balling the Queen