Now that we’ve savored the beginnings of a pumpkin spiced holidays, take a moment to explore the wonders of how such flavors came to define the season. At the first show of the newly opened Museum of Food and Drink (MOFAD) Lab in Brooklyn, “Flavor: Making It and Faking It” takes visitors through a multi-sensory journey of the science, cultural history and the politics of manufacturing flavor.

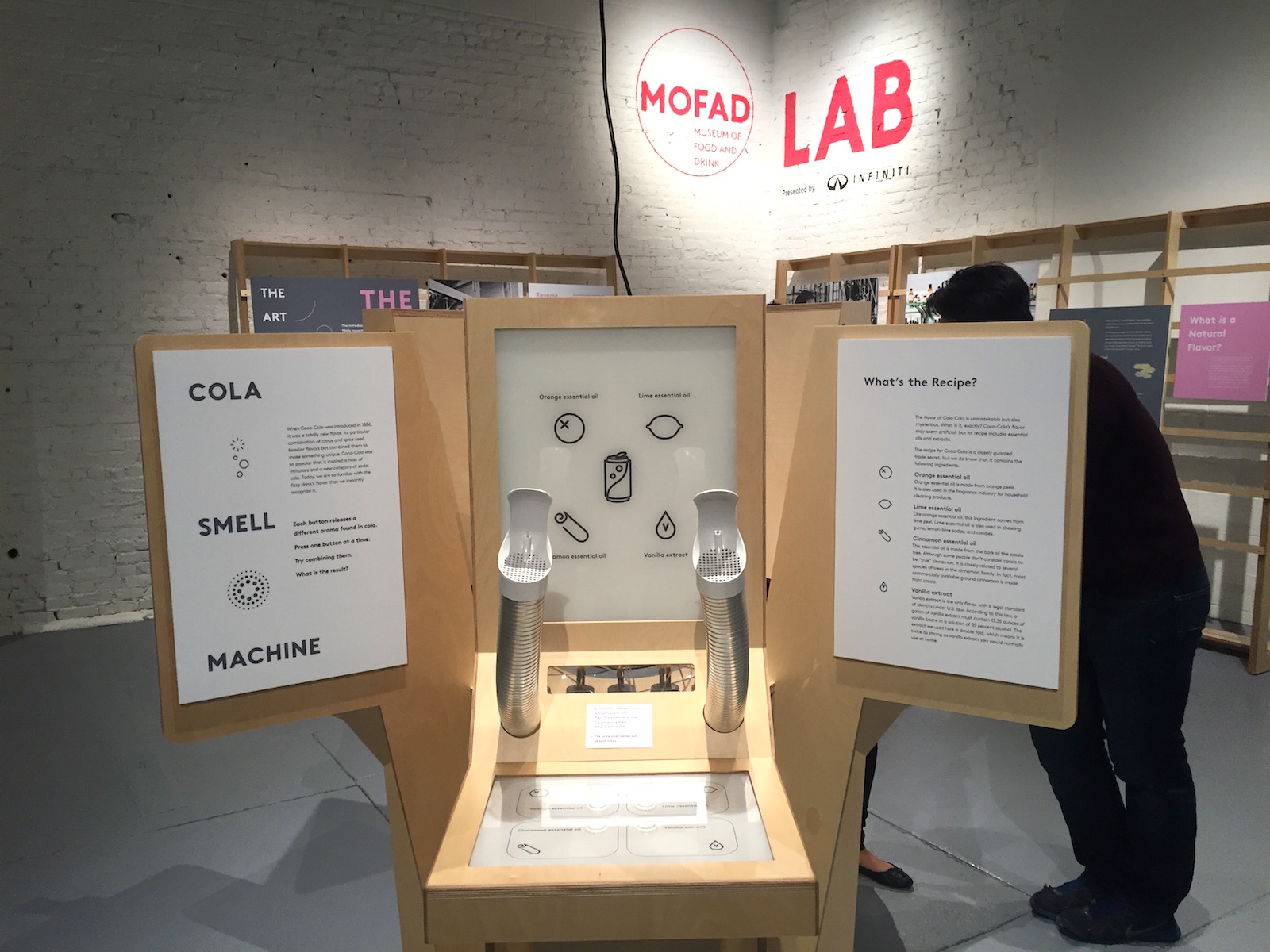

The Smell Synth produces thousands of flavor combinations. Our favorite? Cheesy Popcorn: salt + MSG + butter, sweet cream + cheesy, vomit + popcorn.

The Smell Synth produces thousands of flavor combinations. Our favorite? Cheesy Popcorn: salt + MSG + butter, sweet cream + cheesy, vomit + popcorn.

“Flavor” is a deep dive into two of the most ubiquitous manufactured flavors—vanilla and MSG—with a mix of physical artifacts and engaging storytelling elements. “We decided to tell the story of how the flavor industry separated flavor from food and came to dominate what we eat.”” explained Peter J. Kim, MOFAD’s executive director. “There’s pleasure in flavor but it is also our body’s way of detecting sustenance. And with the flavor industry, we start at a specific point and jump into controversial territory where there is a lot of misinformation.”

Consider that vanilla, that stand-in for bland, was once one of the most rare and expensive commodities. Derived from the bean of a Mexican orchid, Spanish conquistadors brought vanilla to Europe in the 16th century setting off a trans-Atlantic demand for the perfume and flavor. For centuries, Europeans tried unsuccessfully to cultivate vanilla pods in greenhouses and the tropical colonies—unbeknownst to them, only a particular Mexican bee can successfully pollinate the flower. At the MOFAD Lab, visitors discover how the pursuit of the exotic flavor of the vanilla bean led to the culinary alchemy of lab-produced flavors that dominate our supermarket shelves today.

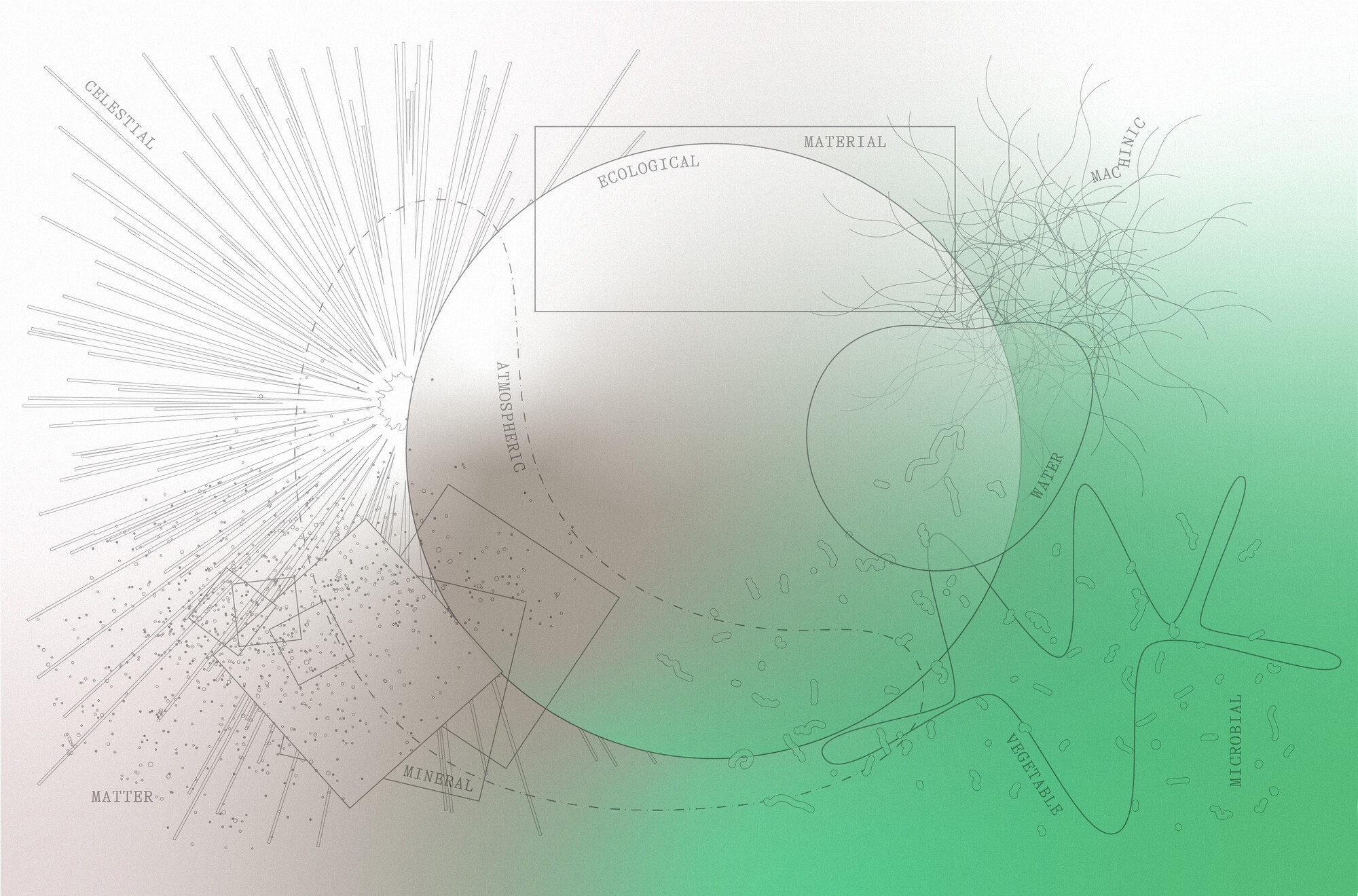

Graphic Design for the exhibition is by Labour.

Graphic Design for the exhibition is by Labour.

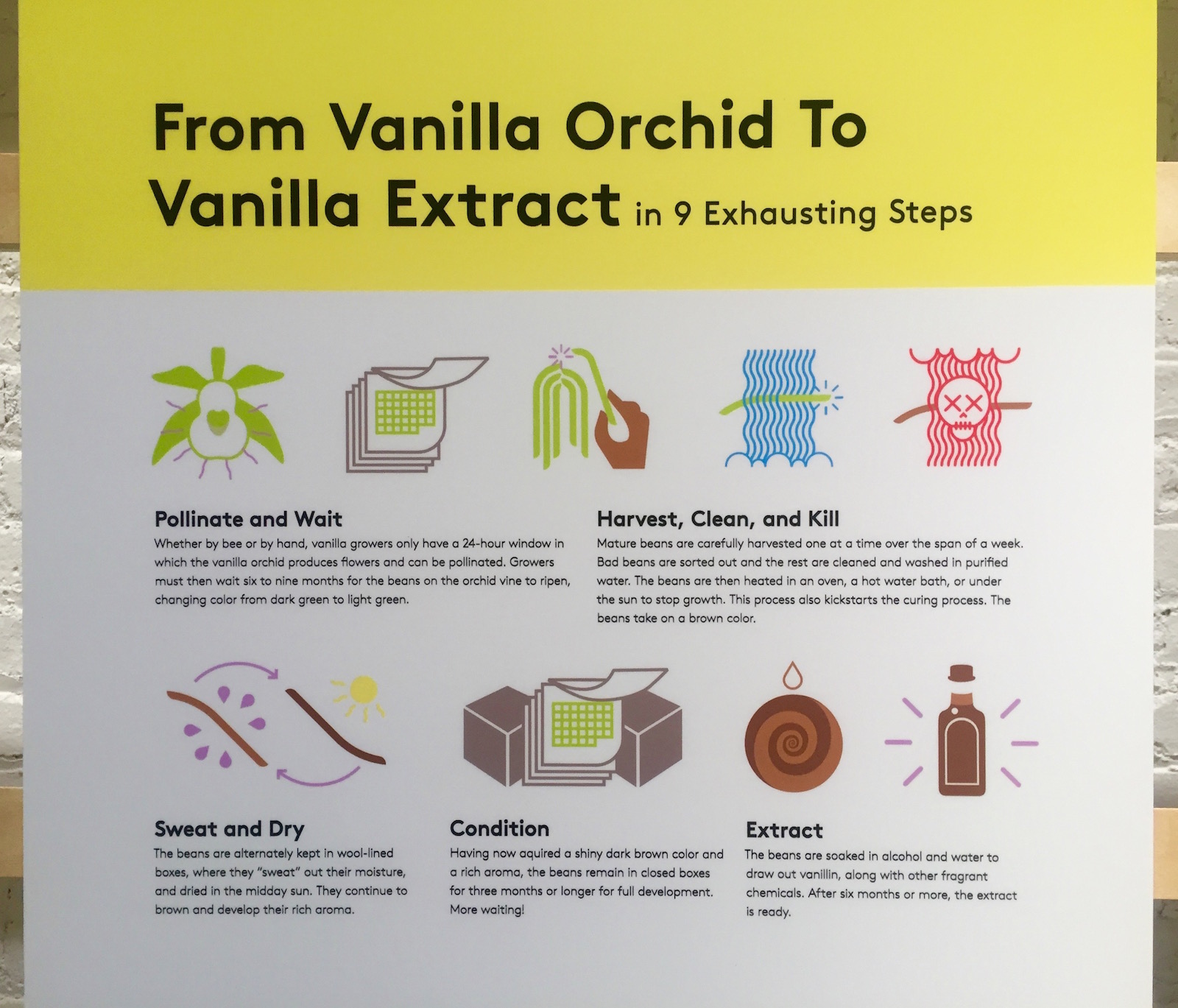

The exhibit includes historical timelines of the vanilla bean’s journey from Mesoamerican trade routes to Betty Crocker cakes, illustrated explanations of the labor-intensive process of cultivation to extraction, and installations showing the various materials explored for manufacturing vanillin, the chemical twin of naturally occurring vanilla. Who knew that the chemical vanillin could be found in pine bark, clove oil, paper, rice bran, petrochemical compounds and…brace yourself, cow dung? These experiments in organic chemistry opened up a whole new industry of food science and turned some of our most ubiquitous food and drink products into brands. What would Coca-Cola or Oreos be without it’s propriety mix of flavors?

Installation on the history of MSG.

Installation on the history of MSG.

MSG, the oft maligned umami-bomb of “Chinese restaurant syndrome,” was identified by the Japanese chemist Kikunae Ikeda in 1908 when he sought to duplicate the savory flavor of kombu, and edible seaweed often used in Japanese cooking. During the post-war years, MSG became a hugely popular addition to American pantries and was even touted as “The Third Shaker.” But after a misinformed Chinese restaurant food poisoning scare, MSG quickly declined in popularity. Umami-rich glutamates like MSG occur naturally in foods like shellfish, fish, parmesan, mushrooms, cured meats and fermented sauces and foods. While star chefs the world over are lauded for pumping up the umami flavors in their food, MSG now occupies a confused place in the culinary landscape.

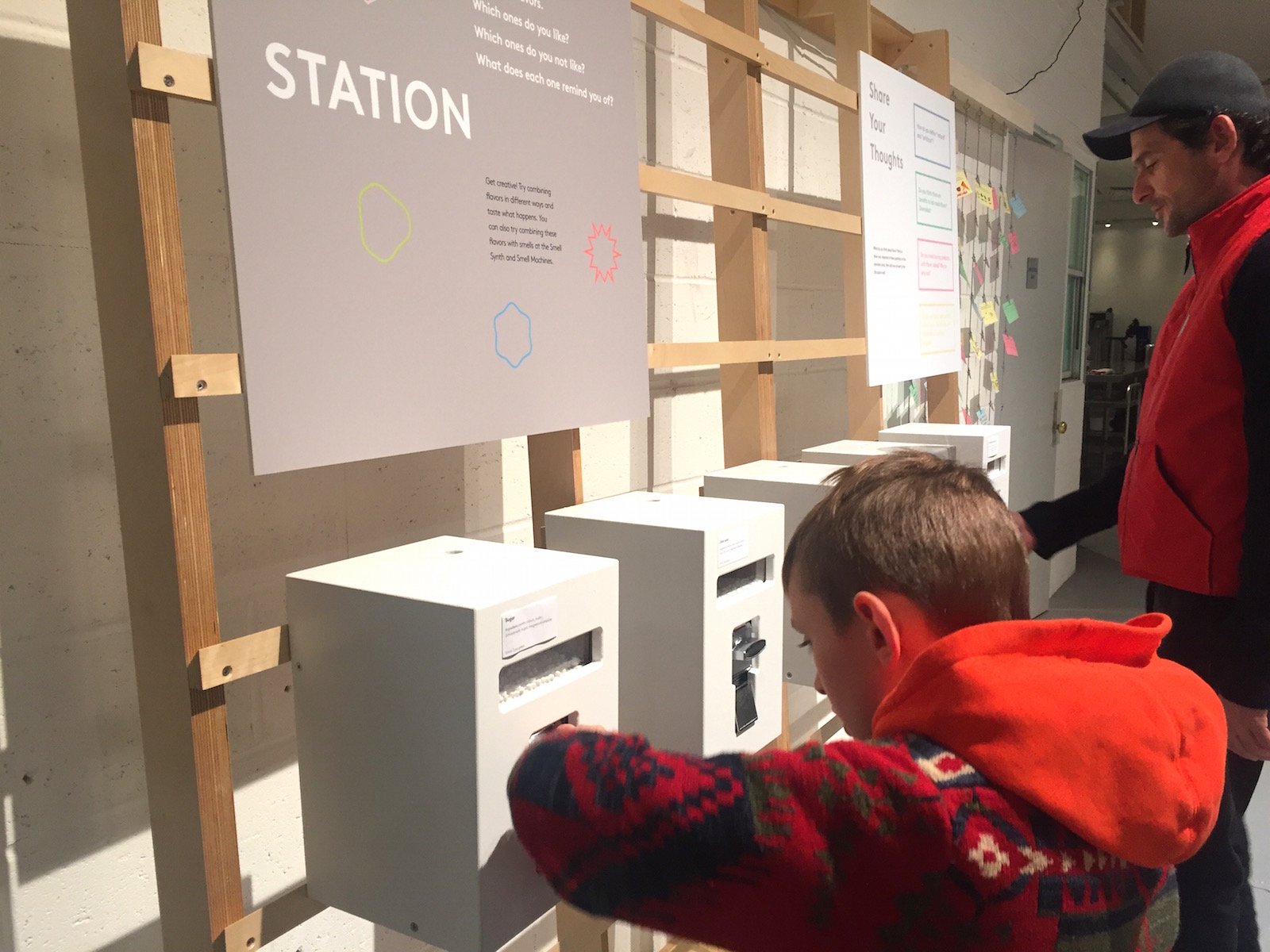

The flavor station dispenses pellets of flavor with a twist of a knob.

The flavor station dispenses pellets of flavor with a twist of a knob.

With a twist of a knob, visitors can taste MSG in its pure form and judge for themselves. Modified gumball machines sprinkled throughout the exhibition deliver pellets of flavor—mushroom, seaweed, citric acid, apple flavor and pumpkin spice. The single flavor tabs dispensed might seem simple, but their design took hundreds of trials to develop. “We looked at jelly, gumballs, Listerine strips,” Kim recounted. “Even though tablets are used in confection and the pharmaceutical industry, there is no such thing as a savory tablet.” Maltodextrin, the primary binder for confection, has a sweetness to it. Kim oversaw multiple iterations of the pellets in order to create a simple, single-dose shot of flavor for the exhibition. After months of research, he stumbled on the idea of using potato starch, a relatively flavor-neutral ingredient that dissolves quickly on the tongue. The result is one of the most surprising experiences of the exhibition—the nostalgic joy of lifting a metal flap to discover a tasty treat, dispensed on command.

The most whimsical section of “Flavor” is the Smell Synthesizer kiosks which challenge visitors to determine differences in flavors—concord grape or a synthesized version, “skunk note” or freshly brewed coffee—while highlighting the importance of our noses in determining taste. With a push of an arcade game-like button, the Smell Synthesizer whirrs and the scent of a specific flavor wafts through a nozzle into participating noses.

Dave Arnold, founder of MOFAD, food scientist and the man behind New York City’s Booker & Dax cocktail bar, developed the underlying technology and coded the Smell Synthesizer himself after an inspiring visit to the Monell Center. The non-profit taste and smell research institute uses an olfactometer to conduct research into how subjects perceive and respond to smells. Experiencing the wonders of the olfactometer, Arnold decided to build a similar machine to bring a participatory and interactive element to the show. The resulting Smell Synth is part multi-sensory church organ, part smell-inspired video game—pushing any combination of its single-note buttons can trigger a mixed bag of thousands of surprising flavor scents.

“We wanted the exhibition to be Willy Wonka meets the Eameses,” Kim described the Museum . With lights, smells, science, history and deliciousness served up, MOFAD has designed an exciting experience where food science and history is fun.

“Flavor: Faking It or Making It” is on view now through February 28, 2016 at 62 Bayard Street in Brooklyn, New York.