From MOLD Magazine: Issue 03, Waste. Order your limited edition issue here.

Like most major capital cities, London, where I live, is a city in flux: under ceaseless and enormous change driven by its always expanding inhabitants. The demands placed on its charming Victorian infrastructure means roads and railways are perpetually under rehabilitation to cope with the sheer volume of activity that keeps the city viable.

Photography courtesy of Fatberg.

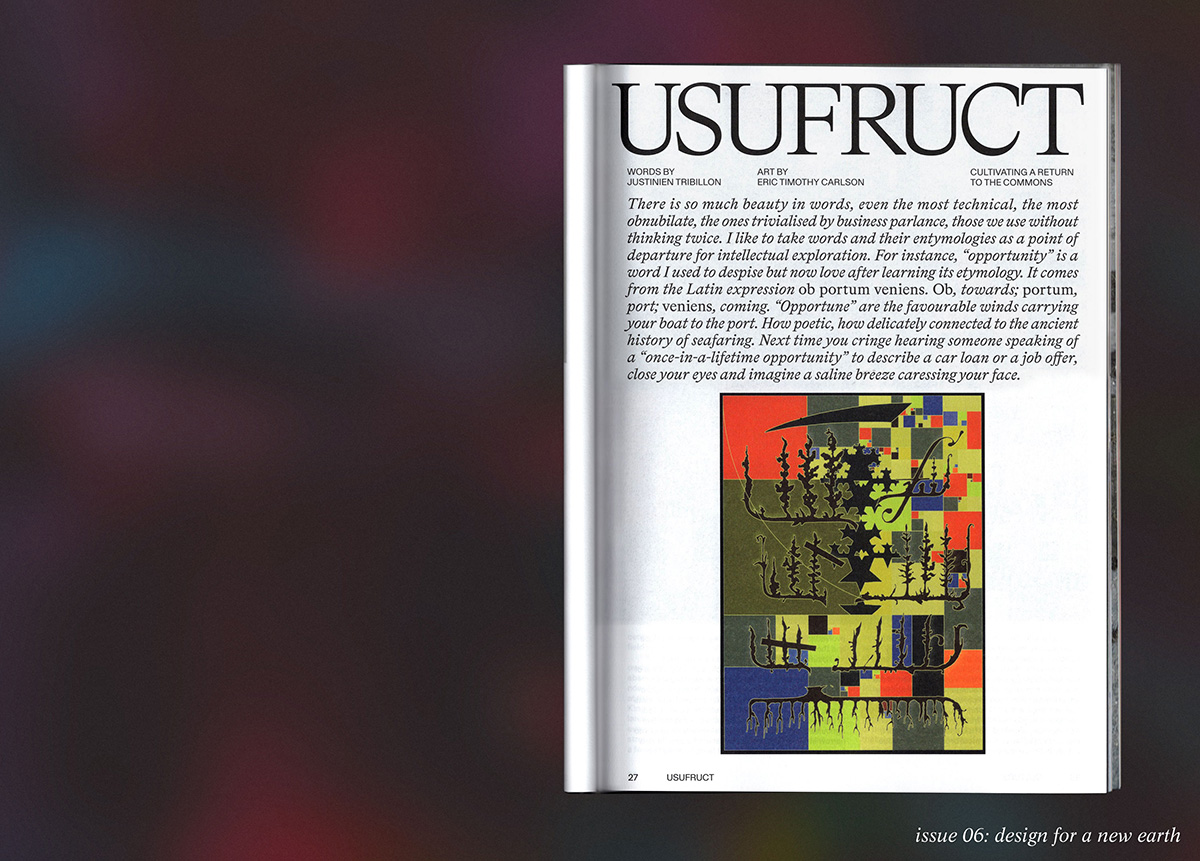

Nowhere else can that old versus new dichotomy be experienced more viscerally than deep within the city’s sewer system. You may have heard of our infamous fatbergs: colossal objects formed from domestic and industrial cooking fat disposed of down drains, which congeals and eventually cause blockages. The Museum of London recently exhibited remnants of the Whitechapel fatberg that went viral when discovered in 2017. Weighing 130 tonnes and measuring 250 meters long, it was one of the largest fatbergs ever discovered. With a sample removed from its original context and installed in the museum, the so-called “Monster of Whitechapel” helped bring into focus the labor of maintenance performed by engineers who work in these sewers and, more broadly, the politics of disgust.

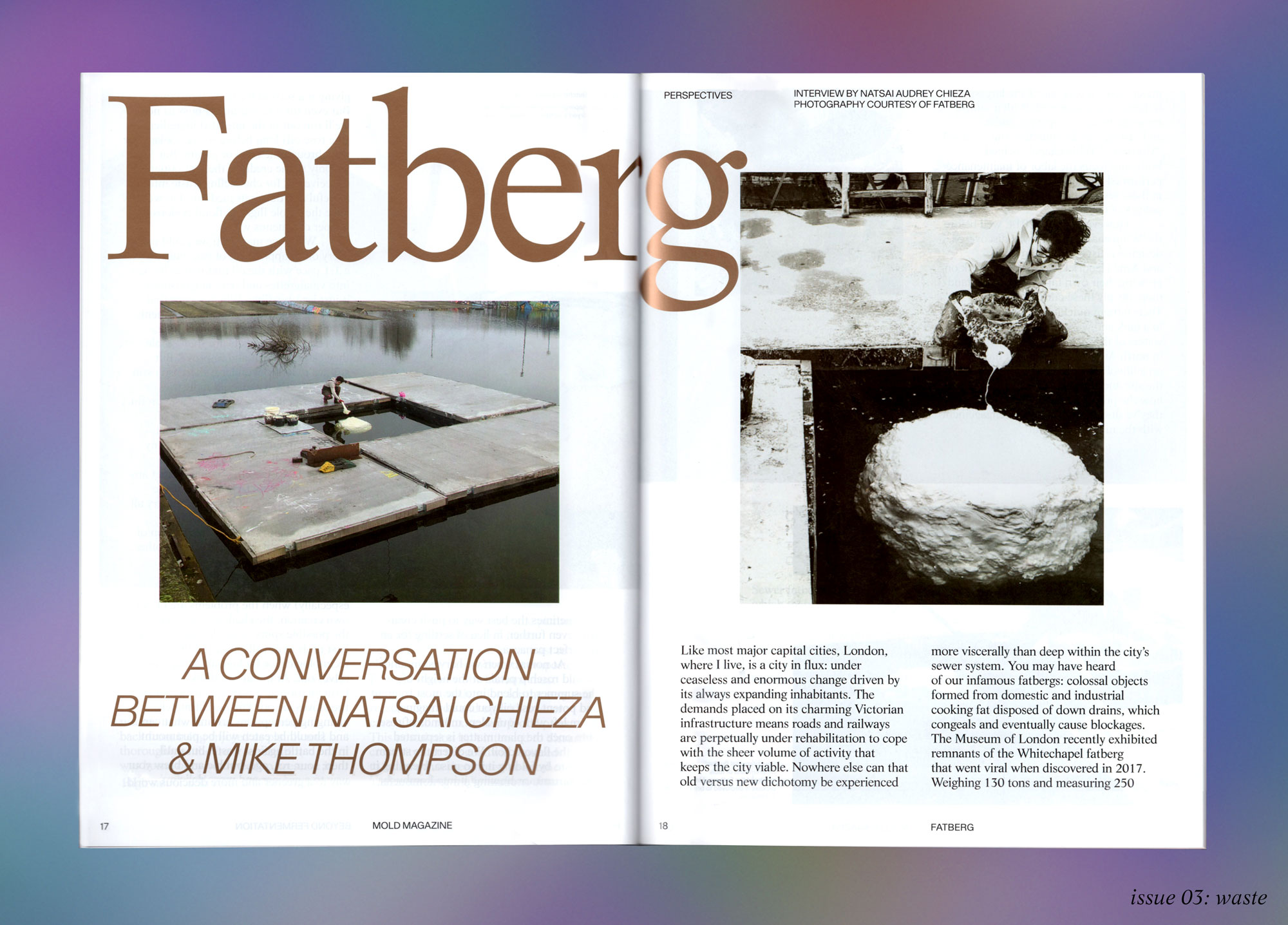

However, back in 2014, well before the Whitechapel fatberg was discovered, designer artists Mike Thompson and Arne Hendricks commenced work on growing their own fatberg to understand more deeply these curious objects. Their fatberg quickly outgrew its home in a tank and was moved to the open waters of the NDSM shipping wharf in north Amsterdam, where it has taken on a life of its own. I recently visited the site and caught up with Mike to learn how the project has evolved and what they’ve discovered from their engagement with the materiality of fat.

N. Chieza:

Could you share your insights into “wild” fatbergs and what enables them to accumulate tons of matter in our sewer systems?

M. Thompson:

Sewer fatbergs originate from liquid fat washed down into the sewer, which then, slowly, solidify. Their growth is a cumulative process that takes place over a relatively long time during which they can grow to this really, quite profound scale. Thanks to Thames Water, we had the chance to see one ourselves. Between Whitehall and New Scotland Yard, there’s a 25-meter stretch at a junction where sewer waste coming from the East End of London meets this particular place, causing fatty build-up to occur. As far as I understand, all it takes to cause a fatberg is some sort of non-human waste, like a plastic bag, to get flushed down and then snag. They refer to it as a reversed glacier—once it solidifies, new fat butts up against it and it starts to grow.

There’s this preconception that you’re going to see something like the fat you dumped down the sink, whereas it’s more akin to looking at soil—the top layer almost smells earthy. When you peel that layer back, you see a thriving ecosystem of worms, flies and moths, all feasting on this congealed mass of waste. Of course, life doesn’t see this as waste. Life just consumes it and reprocesses it back into the ecosystem again. We found it really fascinating that fat, in this instance, starts to take on materiality that’s outside of our ideas of what you might expect fat to do. If you put your foot on it, like a spongy mattress it will bob up and down on top of the sewer water. Equally, if you examine chunks of the decomposing bits, it is like limestone.

We’re fascinated by how fat becomes a material for production, rather than just a waste material, and seeing how fat accumulates, and then transforms in this setting, becomes quite inspiring.

N. Chieza:

How does the super-organic, thriving, geological, materiality of wild fatbergs contrast with your laboratory prototype? Where does your fat come from? What does a fatberg supply chain look like?

M. Thompson:

Our fat comes from a variety of sources including butchers and waste fat donations from people. What we find fascinating is that the different kinds of fat express slightly different materiality. So, for example, beef fat tends to be relatively waxy, pork fat much more buttery, and something like palm oil, or palm fat, much more oily. By combining these characteristics, we end up with a material that’s much more practical for what we’re trying to achieve.

We render it and purify it into its most basic form. In that sense it differs quite significantly from the fat you see in the sewer. So the wild fatberg is more of a composite material, whereas we’re working with something more pure.

N. Chieza:

Are there any processes, or tools that you’ve had to invent to transform this material and to build with it?

M. Thompson:

We’re building something that no one’s really tried to build before, so we’ve had to create the knowledge as we go.

To create our island, we started with one singular drop. For this, you can start with something as simple as a pipette or syringe. But you quickly end up having to move to much larger tools like squeeze bottles. Now, working with larger volumes of fat, we’re having to fabricate tools ourselves, so there’s a lot of making tools on the fly, constantly spotting and responding to different behaviours like changes in weather and therefore temperature.

N. Chieza:

Do you think your fatberg is living a life specific to its environment? Could it be replicated elsewhere, and show the same behaviours?

M. Thompson:

I think there’d be similarities but some differences. You’ve got to remember that the Fatberg started off in a small tank with relatively clean water—which is quite a hermetic context. Even in the lab we noticed very quickly that slime molds move in and start to grow on this thing under water: we even put it under a microscope and looked at what was growing on the fat. It was teaming with microscopic worms and all sorts of other life forms! We then moved it to open water because there was this need to increase the scale. It’s now in relatively clean open water, facing directly onto the river IJ in the north of Amsterdam, moving out towards the estuary, but the water is full of all sorts of life. Recently, the slime molds have been thriving and there’s evidence of algae starting to grow. There were quite a large number of freshwater mites swarming around it yesterday and even small freshwater shrimp feeding off it. So, the Fatberg has become its own ecosystem—life is very much starting to interact with it and it’s a living, thriving thing.

We’d always fantasized that when it got massive, you’d see flocks of seagulls flying around it. Well, now that’s literally happening! The minute we walk away from the pontoons where we’re working, the seagulls are in there picking up any waste material that’s been left around. We’ve even seen ducks on top of the Fatberg, feeding on it. So, they’ve very much taken it as part of their ecosystem. You could argue if you move it and put it into another location, then the kind of microfauna that would start to frequent it would potentially be quite different.

Now that nature’s interacting with this as well, we’re finding that the remnants of slime molds and bacteria are all being trapped inside. Fat has an almost time capsule-like property: there’s a reason people use oils to create perfumes; fats are able to trap certain odors. You can almost say that every drop we add, every layer that gets created, is trapping a moment in time within it.

N. Chieza:

What kind of constraints have you faced as you’ve traversed scales, from the encapsulated, semi-sterile environment of the tank to out in the water?

M. Thompson:

As far as we’re concerned, we are agents for fat. Fat is telling us we have to accumulate fat, build this island, and it has to be as big as possible. It’s about confronting everybody with this material by giving it an autonomous presence.

We’re already at 1.2 tons. We’re at a point with the scale where another 60 kilos is being added today— quite a large quantity of material. But, that doesn’t look like an awful lot anymore. We calculated that five tons would mean that the Fatberg has a diameter of about two meters.

The challenge we face—because 90% of it is under water at any one moment—is that it’s probably going to touch the bottom of the basin its in, and so it’s going to need moving. So, there’s a challenge of location, and getting hold of the kinds of volumes of fat that we need—no longer domestic quantities but not quite industrial, yet. So there are all sort of logistical challenges just to do the work.

N. Chieza:

And these become a part of the design process of making.

M. Thompson:

Yes, absolutely, this project is really about storytelling and story making. All of these challenges are part of that story. It becomes a way to talk about how we’re engaging with this material in ways that we currently don’t. We can confidently say that we’re the most skilled fatberg builders on the planet. It’s about how you bring these very disconnected themes and topics that relate to fat in dialogue with one another in order to understand it from a different perspective.

N. Chieza:

What are some of the unexpected narratives, mythologies, practices, that you’ve encountered in fat making?

M. Thompson:

It’s more to do with where we’re doing it. The NDSM wharf has been reformed into a cultural area, but it’s steeped in shipping history. We’re at the bottom of this ramp where they used to launch huge ships into the water. We discovered they used to use whale oil as a runner to slide the boats down it into the water. So there’s a history of whale blubber being used as part of the ship building process. Fat is just a regular material. In some respects, the Fatberg is still part of that process.

Lately, I’ve been considering the cultural aspects of fat and how people relate to it. The immediate response is to find it disgusting. But, I think that is a sign that people are intrigued by something they wouldn’t come across every day. People will immediately start discussing the Fatberg in a way that gets past the tried, tested and quite limited lexicon we tend to have for this material.

N. Chieza:

That’s it. It’s that thing out of place, not knowing how to contextualize it. Instinctively, there’s an apprehension but, by understanding it, it can all fall away.

M. Thompson:

Yeah. I think the Fatberg throws the idea of “what is clean” up in the air. The notion of cleanliness is something that we, as humans, have developed over a period of time towards fat and our relationship with bacteria. But because our Fatberg has become part of this ecosystem and now that we’re around it all the time, we have a totally different relationship with it.

It is often said that a weed is a plant out of place. The Fatberg challenges our perceptions of waste by re-contexualizing it in a new place and asking what new relationships can we begin to catalyse? This whole systems approach to production and consumption is circular in nature. New perspectives could offer opportunities for food waste to help feed a city, or make the food system more biodiverse.