This story is part of MOLD Magazine: Issue 02, A Seat at the Table. Order your limited edition issue here.

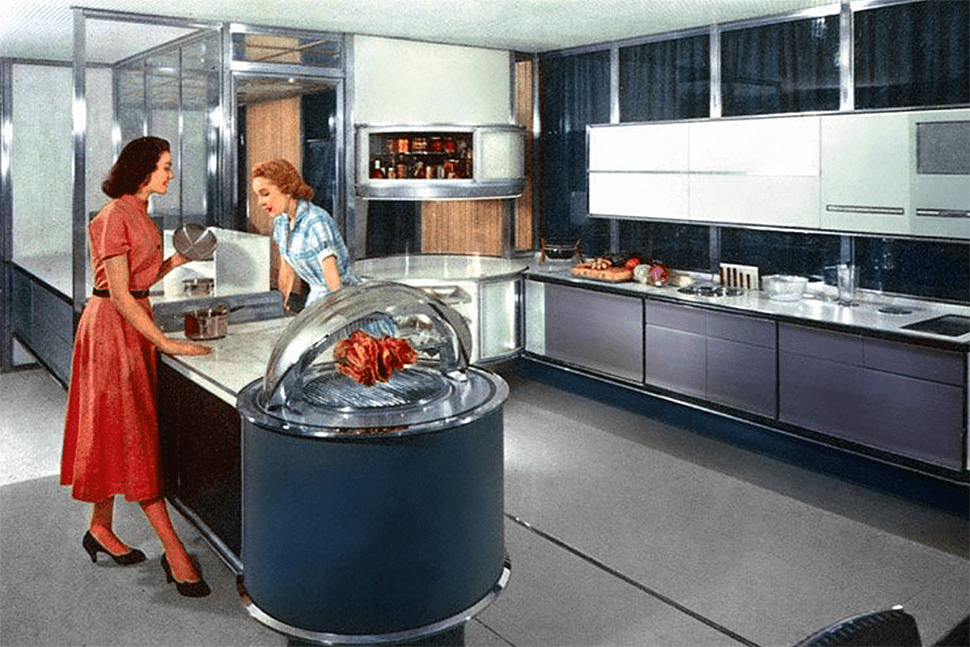

In 2005, molecular gastronomy had transformed the downtown food scene. Science collided with cooking and what was once known as a carrot could now be a cloud. The excitement and invention that permeated those times was intoxicating. I was working as a waitress in the new wave of modernist restaurants and loved the theater of life in these spaces—the daily performance we’d all prepare for, serve up and close out each night, as diners would cruise in and out of our doors, delighted by the radical flavors they encountered. That sense of transformation, pleasure and creativity made me fall in love with the world of food and put me on the path to becoming a food designer. The journey speaks volumes about how we might approach the future design of food.

Leaving the restaurant world, I studied industrial design and learned that design was nothing more (or less) than a plan or convention for the creation and construction of some thing that solves a problem in our lives. Be it shoe design, furniture design or graphic design, the design process delivers artifacts that help us do everything from run faster to see better. On deeper inspection, I also learned that the best-designed stuff fulfills emotional needs: subliminally screaming, “YES YOU CAN! There ARE other ways to live, act, run, be! JUST DO IT!”

Marketing jargon aside, this emotional connection to new possibilities was the same reason I had fallen in love with bars and restaurants. Design was more than stuff; it was a structure within which to create abundant possibilities, exercise wild creativity and actively reinvent our lives.

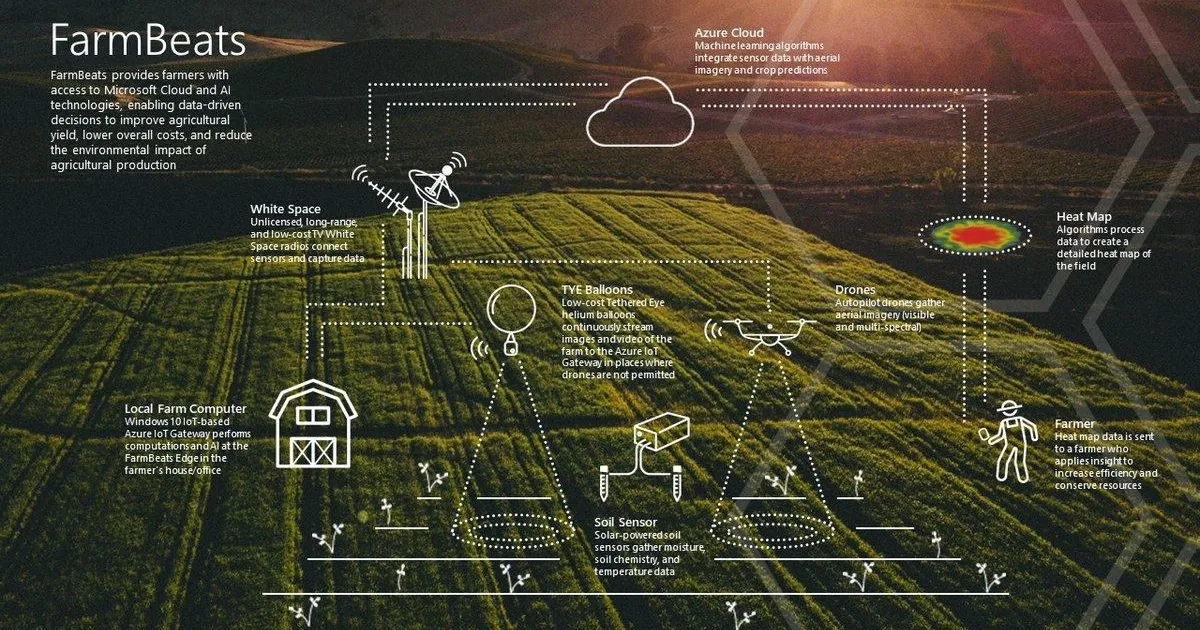

The advent of digital technology has moved us closer to this insight. What was traditionally defined as design through shape, color and form is now talked about as the business of systems, processes and experiences. Be it on-demand ride-sharing in lieu of taxicabs, the Bitcoin as a replacement for the dollar bill, or apartment swapping instead of hotel rooms, the future of design is less about single artifacts and more about an ecology where every thing is connected, communicative and part of a greater network that affects our entire life.

Professionally, I spent a few years working as an industrial designer while this new landscape emerged, but I quickly found myself back in food. As an industrial designer, I was trained to leverage the properties of whatever material was at hand, and food proved to be endlessly inspiring: serving up new feelings, sounds, smells, tastes and textures with its multisensory properties. By adding technology to the mix, I started to think of food in a whole new way. Consider this: from feeding our biology, to bonding communities, nourishing families, stimulating economies and conveying emotions, the ritual of eating reaches far beyond mere ingredient. I started to think of food as our first “connected device”: bringing together planet, people and politics through its design.

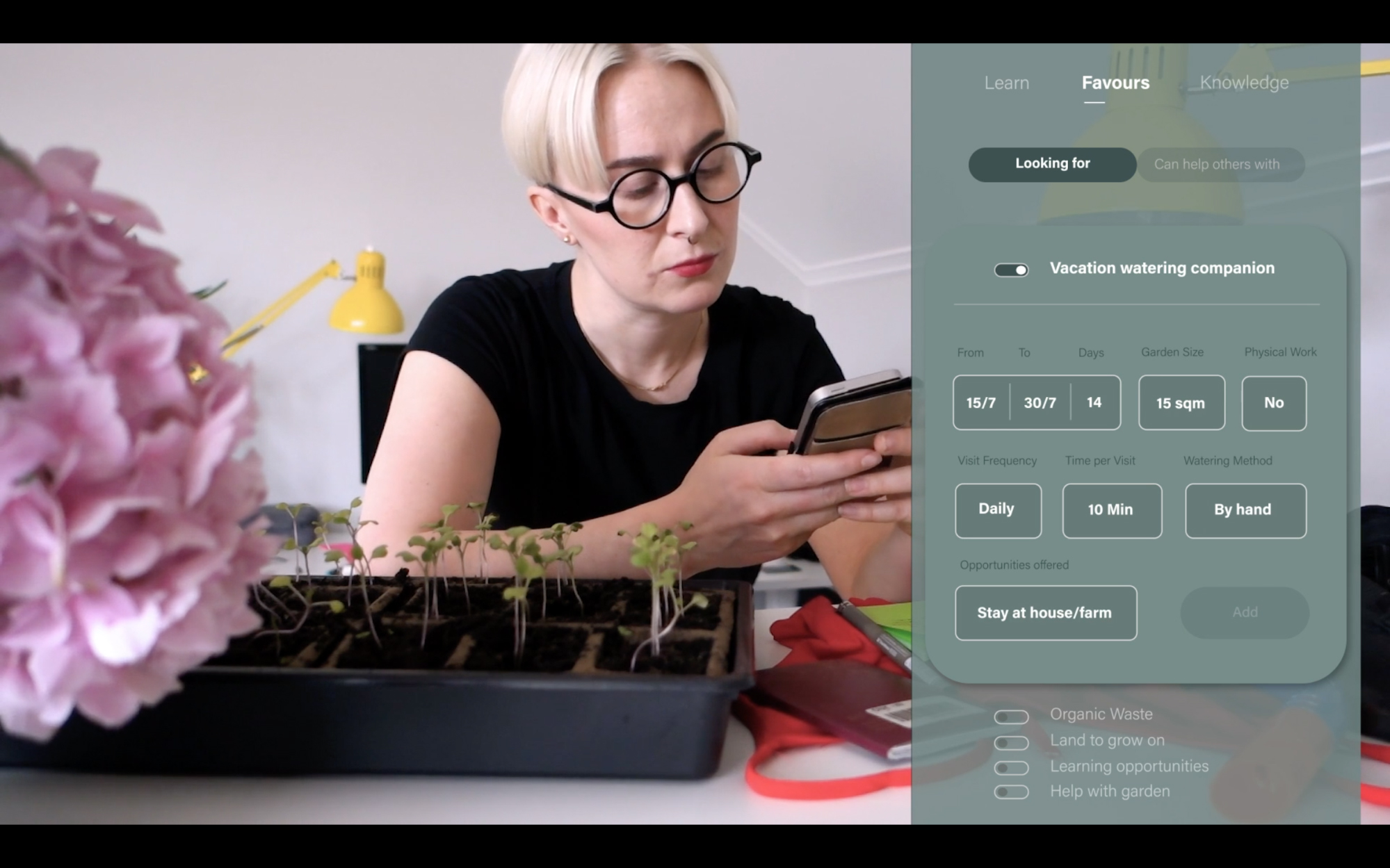

In this light, it no longer makes sense to think of designing for food as just a plate, a table or a fork. Emotions and experiences are the lingua franca of the modern world. By using technology as an ingredient, food can now be used for more than just chew, swallow, repeat. Consider businesses like Seamless, who use tech to create instant access by breaking down the walls of a restaurant and serving us meals directly in our homes. Or companies like City Farms whose technology upends traditional agriculture by growing crops indoors. And products like Sprouts.Io, that allow ingredients to become canvases for creativity by empowering cooks to program in-kitchen climates and design tailor-made produce. These applications demonstrate how food can be an ingredient for the new experiences of a tech-centric future: expanding efficiencies, transforming ecologies and increasing control. Yet, humans do not live on bread alone. And while technology has drastically improved many parts of our food system, one, basic, necessary piece is rarely addressed: human emotion.

I fell in love with restaurants because of the feeling in them—the wonder, delight and transformative nature of a great dinner is unlike anything else in the world. How can our future catalyze more of this beauty in the world? At heart, the real ingredient in transformation is discovery. Great meals teach us something new, as do great relationships, products and experiences. In my practice, I am dedicated to fostering this way of being in the world and create dinners, products and pedagogy that use food to reveal the hidden possibilities in our world.

For example, in 2010 a “new” crowdfunding technology enabled What Happens When, a pop-up restaurant I co-founded with Chef John Fraser and designer Elle Kunnos. As one of the first food projects on Kickstarter, the restaurant transformed every 30 days based on patron suggestions. The result tasked us with entirely redesigning the restaurant interiors, menu, soundtrack and service overnight. Thanks to Kickstarter, the project became more than just a physical space, allowing patrons to follow the progress online, comment and become part of our creative process. In the end, the pop-up was less about the food, but more about the process and discovery of “what happened next…”

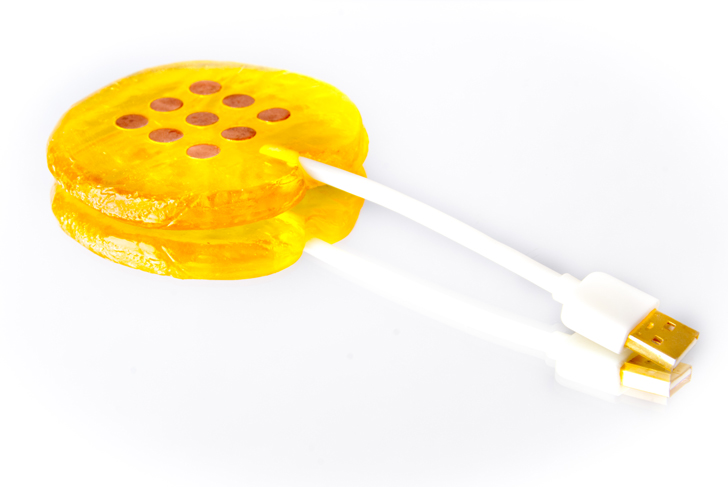

Soon thereafter, the accessibility of sensing technology served up new ways of experiencing the act of eating. In collaboration with artist and designer Carla Diana, we experimented with capacitive sensors in ice cream and discovered the Lickestra!, the world’s first licking ice cream orchestra! By using this technology, the act of licking triggers a musical riff, transforming a group of eaters into performers and radically reimagining what an everyday act of eating might be.

New technology has been a constant source of wonder leading me to develop several more firsts, including a Cotton Candy Theremin that reacts to the gestures of spinning fairy floss, Ice Block Speakers that sing when touched, a Scent Organ that delivers a multisensory orchestra when played, and more wild creativity than my younger self could have ever imagined.

But the greatest lesson herein is that “new” shouldn’t be the catalyst for the next generation of dining rituals. True invention comes from embodying possibility and fostering curiosity. Technology can facilitate innovation, but real transformation only occurs when discovery is achieved. What if we imagined our future dinners as just that? Laboratories for learning, wonder and discovery. What might that do to our daily life?

One of my heroes, the neuroscientist Oliver Sacks, stated, “We are not given our life, we make our life.” Our materials, choices, projects and relationships are the ingredients of our lives—how we design this recipe is how we consume our everyday. As technology rages forward, politics collide across cultures, and natural disasters become commonplace, I can think of no better material (or metaphor) than food for reimagining how we nourish ourselves and our planet.