Shelf Life is a monthly series at MOLD that explores how we eat at different stages of life.

Eating is as much a psychological exercise as it is a physical one. It’s our response to boredom, stress, or celebration; we use phrases like “cheat days” and “guilty pleasures” to simultaneously communicate how we’re eating and feeling at a given moment. Deciding what to eat is as much about nutrition as it is familiarity, identity, and creativity. Most of these associations begin to develop at the age of two.

Around this time, toddlers cross an important psychological threshold and first recognize themselves in a mirror. Successfully passing the “mirror test” signals the beginning of a child’s self awareness, and with that comes the newfound concept of independence. Independence is hard for a toddler to express when they don’t have control over much, but eating—determining what they won’t eat, what they will, and how long they take to do so—is one of their first acts of solo decision making. Food is one of our earliest decision arenas and a space where we form habits quickly; thus, the foods we eat, our mealtime patterns, and the utensils we use as toddlers lay the foundation for our relationship between self and food for a lifetime.

Toddlers’ first act of independence is deciding what they’ll eat. Evolutionarily, we associate sweet with safe and bitter with poison, and for children, flavors are particularly intense; a toddler has 30,000 taste buds compared to an adult’s 10,000—which means that exaggerated reactions to new flavors are in-line with what they’re experiencing sensorially. On average, toddlers need to taste a new flavor 10-15 times before it’s familiar to their palette, at which point it becomes less overwhelming.

Part of that palette adaptation means that children naturally put flavors together in unexpected combinations, and the feedback they get about those combinations informs their social outlook on food. Rather than tell children that flavors such as horseradish and chocolate don’t go together, parents can foster an adventurous palette by encouraging kids to imagine, assemble, and test their own concoctions. This concept inspired The Edible Exhibition, a Bompas & Parr and AMV BBDO interactive workshop at the V&A Museum in London that invited 100 children to imagine their “ultimate food fantasies.” Winning entries ranged from glow-in-the-dark ice cream made from carrots to edible bubbles of broccoli and cucumber; all were brought to life at the exhibit and commemorated with edible posters by illustrator Rob Flowers.

The Edible Exhibition. Photo courtesy of Bompas & Parr.

The Edible Exhibition. Photo courtesy of Bompas & Parr.

How can we encourage children to keep experimenting with flavors and other aspects of food, like texture? Kids become acclimated to new sensory experiences best by doing what comes naturally to them—playing. “When you generate these [play] types of environments, kids willingly start touching, smelling and tasting food,” says designer Florencia Sepúlveda, a Royal College of Art graduate and creator of Nico Eats, a tableside toolkit for children. Sepúlveda’s collection includes food mashers, squeezers, and cutters, a kaleidoscope for examining crumbs, and a mixing flask to combine flavors. Most of Sepúlveda’s tools require kids to break down foods into small, irregular pieces—a design based in science. “Children are very good at regulating their intake so they get the proper amount of calories,” says Andrea Garber, chief nutritionist for the University of California, San Francisco, child obesity program. They naturally take more bites of smaller portions of food, preferring a bento box format over a traditional plate. Particularly in Western countries where overeating affects obesity levels, fostering children’s natural instinct to take small bites makes for smarter eating over a lifetime.

Nico Eats. Photo courtesy of the Royal College of Art.

Nico Eats. Photo courtesy of the Royal College of Art.

When toddlers are ready to progress to forks and knives, they have the odds stacked against them. Around the same time that they’re starting to learn to eat at the dinner table, they’re also developing basic motor skills for grip. They’ll first hold utensils as they do other items such as pencils—with a full fist, which can lead to food dropping and frustration on behalf of parent and child. Eating with others is an act that requires accessibility; when viewed through that lens, food-related tantrums carry more sociological weight. A new class of designers is rethinking children’s cutlery sets; rather than selling miniature adult utensils, brands such as Doddl are creating forks, spoons, and even knives that kids can use on their own as they grow. The goal of Doddl isn’t to rush children toward adult table manners; rather, it gives children access to family eating rituals but at their own ability level.

Doddl. Photo courtesy of Doddl.

Doddl. Photo courtesy of Doddl.

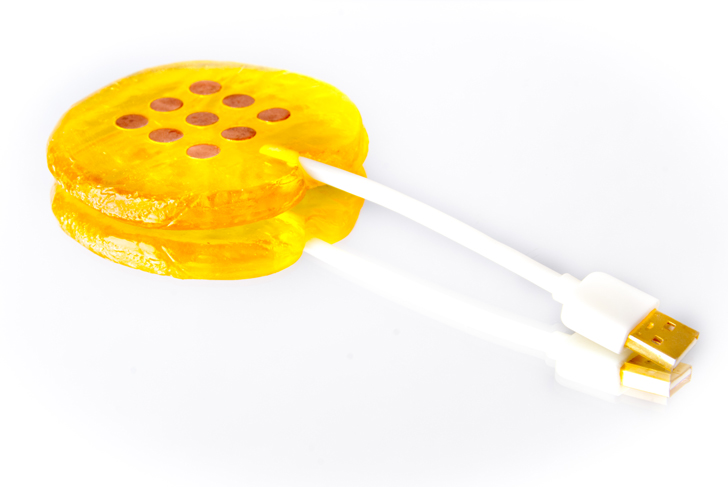

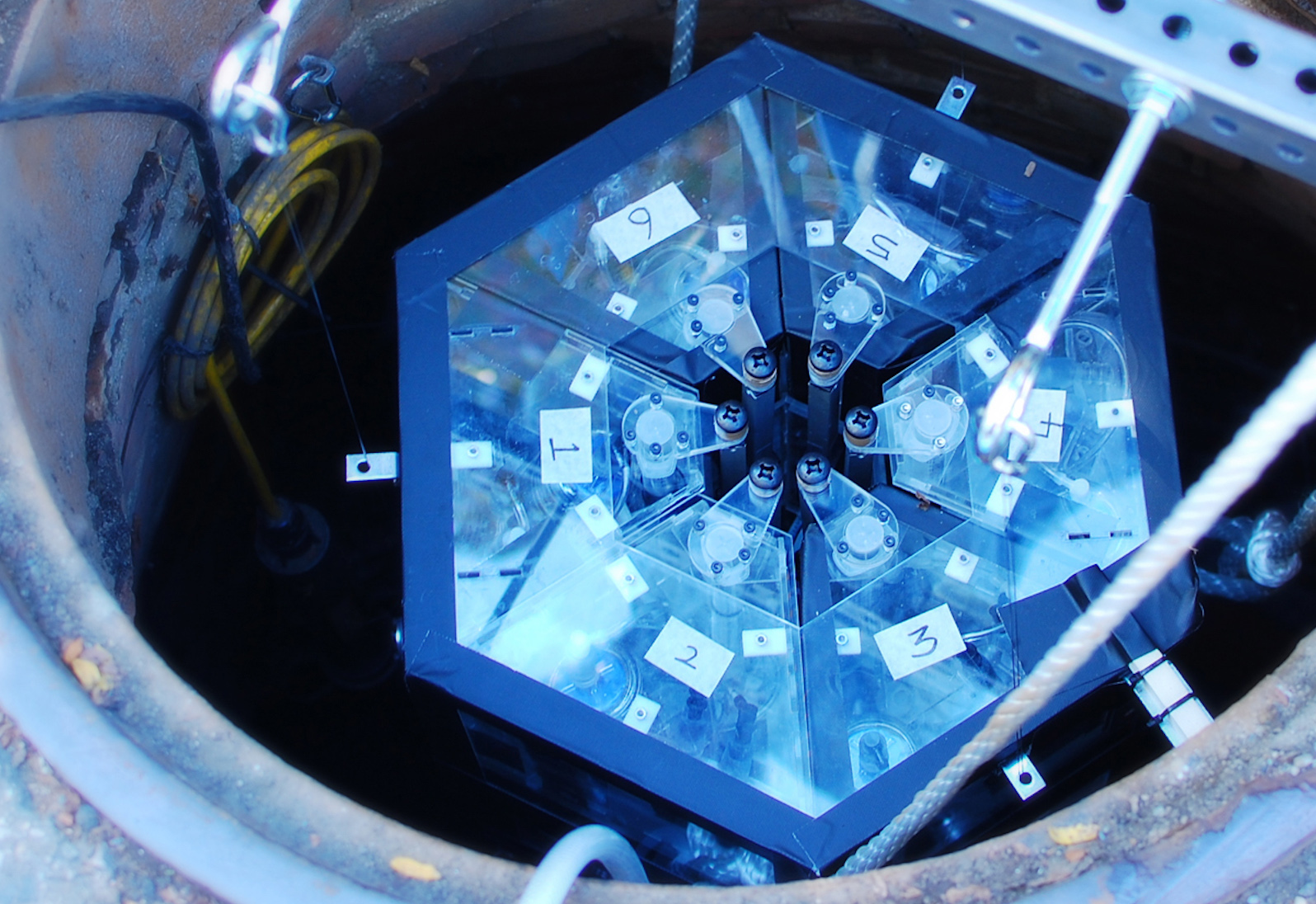

Eating at the dinner table doesn’t only teach us about belonging; it also affects the food we deem edible and appropriate. As we start mastering utensils, we begin to qualify food by how well we could manage them with our toolset. Thus, the utensils we introduce to children directly impact which foods they’re comfortable picking up, prodding, and eating. This insight underlines Tastebugs, a utensil concept by Northumbria University student Jay Crockwell that familiarizes children with an emerging foodsource, insects. An interlocking cylinder of modular pieces, Tastebugs includes a dicer to break insects down, a mill to grind them, and a compactor to create different shapes. Comprised of friendly, geometric forms and figures, Tastebugs makes eating bugs part of normal, everyday food play—giving entomophagy an understood place within a child’s mental kitchen.

Tastebugs. Photo courtesy of 3DHubs.

Tastebugs. Photo courtesy of 3DHubs.

As we raise children in parallel with a changing foodscape, the tools and forms they play with are bound to change. Materials will evolve as we prioritize sustainability goals in kitchenware and packaging; forms will shift as we begin to grow and incorporate new ingredients,;and rituals may even change as homes and schedules become less fixed. Yet the trend toward giving children more autonomy in eating is set to endure. By teaching our children to eat at their own pace and with their own creativity, we set the stage for a more curious and expansive relationship to food.