Although restaurant menus insist that an ideal kid’s meal is breaded chicken with a side of fries, research shows that eating a range of foods early in life contributes to overall well being late on. But cultural conditioning combined with extra-sensitive tastebuds mean kids rarely clamor for the leafy greens their parents would like them to eat. This is the conundrum that Royal College of Arts alum Florence Sepulveda was seeking to settle with her project Nico Eats, a set of inventive utensils that encourages kids to experiment with their food.

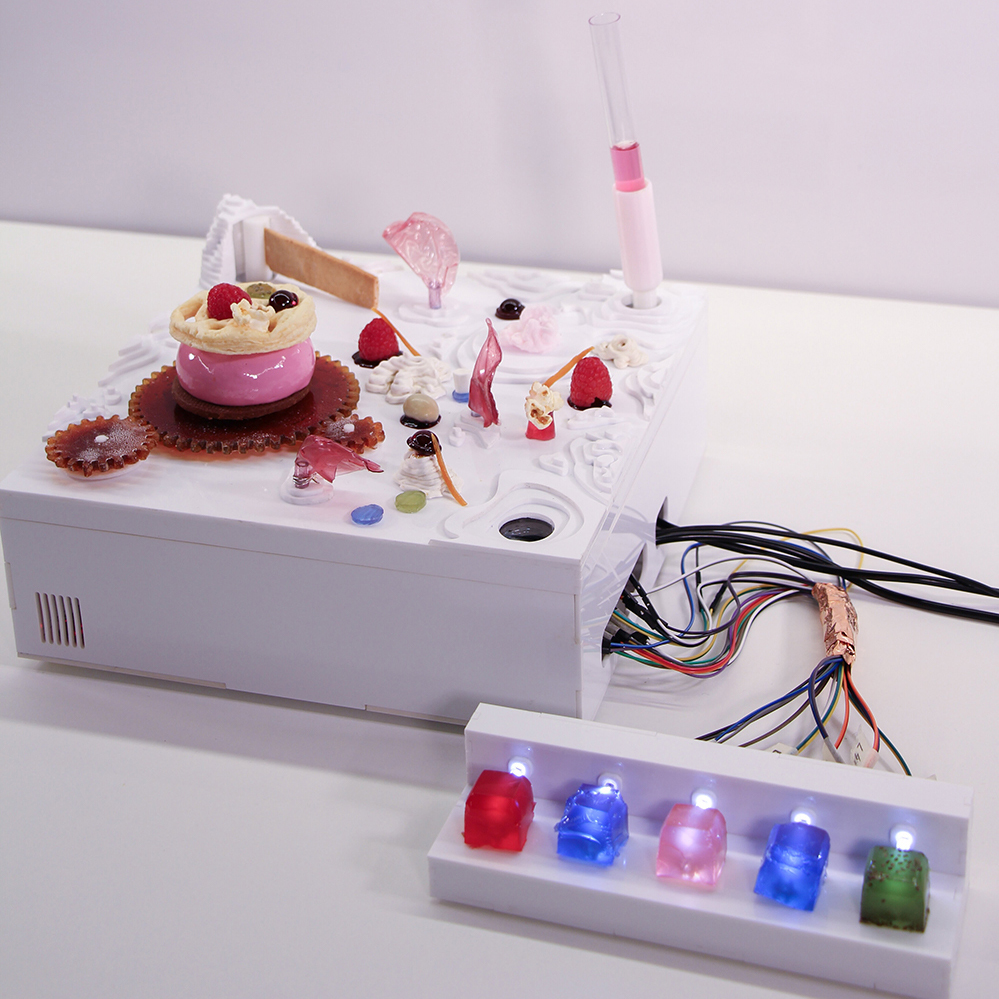

Nico Eats is best likened to a toolbox. It’s full of instruments that kids can use to approach food as a scientist approaches an unknown material in their lab. There’s a set of four long stick-like implements with different shapes attached at the end that kids can use to touch the food, take samples or test its texture. There’s a stethoscope that brings a health aspect into food and a series of beakers that allows kids to further scrutinize it. Together the tools model a multi-faceted disposition toward food that teaches kids to interact it with curiosity and awareness.

Taking the idea of science allows kids to approach the food at one remove—they’re not thinking about eating it, they’re investigating it. Through the process of investigating they turn an unknown entity into a known one, but they also remove the idea that they “should” eat it. As anyone who has ever seen a kid try to eat clay knows, children tend to be more interested in consuming forbidden things. Thus, allowing them to interact with food as they interact with non-consumables paradoxically makes it more interesting for consumption.

Yet this makes the idea of a stethoscope interesting as it might seem to involve health into this discovery kit. While this implement might initially evoke images of doctor’s offices, its appearance in Nico Eats alters the roles that kids, food doctors usually play in this equation. Instead of being examined, the kid turns into the examiner, giving them a feeling of authority and power. Food becomes something the child may identify—it, like the child, is subject to analysis. Instead of being something “good” or “bad,” “healthy” or “unhealthy” foods under inspection become a source of general interest, potentially lowering the barrier to consumption.

Sepulveda also created a set designed around cooking called Nico Cooks. With pastel-colored tools that look like a cross between what you’d find in a kid’s science kit and in a toy kitchen, Nico Cooks shifts the idea of cooking as a duty or as nourishment to a process of exploration and creation. Mash something in the bowl, put it in the blender, try to mold it—the end goal of playtime ceases to be about eating and becomes a way to understand the world.

While a kit that allows kids to play with their food offers a potentially fun way to make a more diverse range of foods palatable to kids, there are still many potential pitfalls that would keep the kit from enabling children to embrace a wide diversity of ingredients. Parents might encourage kids to play with certain foods, but not others. Kids might be more eager to play with certain foods or not others. This is all fine. The real potential of Nico Eats lies in its ability to help kids foster a curious attitude toward food that they take beyond playtime, and that might not have an immediate impact on their diets.