This story is part of MOLD Magazine 02: A Seat at the Table, exploring how tableware and furniture can shape new dining rituals. Order your copy of the magazine here.

‘Optimal design will increasingly come from reverse engineering the processes of the mind’ (Spence & Gallace, 2014)

Let’s begin with a bold statement: The best recipes don’t make the most delicious experiences.

In the last decade, a field of scientific research coined gastrophysics, a blend of experimental psychology and cognitive science, has provided evidence that the pleasures of eating are not just about the physical and molecular properties of food or drink. It can be said that flavor is a perception (not a sensation) created in our brains (not in our mouths), informed by the integration of information coming from all our senses. Vision, touch, olfaction, audition and, of course, taste, all play a role in modulating our experience of foods. Eating might be the most multisensory experiences a human can live, yet, when designing foods, we mostly think of what happens in the mouth: texture, aromatic complexity, taste balance, temperature. While these aspects play a fundamental role, the “everything else,” such as expectations, atmosphere and social conventions, model our experiences much more than we imagine.

Amidst the complexity of food experience, when it comes to designing flavor, there is one approach that is rarely acknowledged and probably from which there is most to gain in terms of quality of ritual, purpose and enjoyment: the tools we use to contain and bring food to the mouth. Indeed, cutlery impacts our enjoyment much more deeply than we think, and its influence is broad, affecting taste perception, value perception, attention and the way we engage with the food.

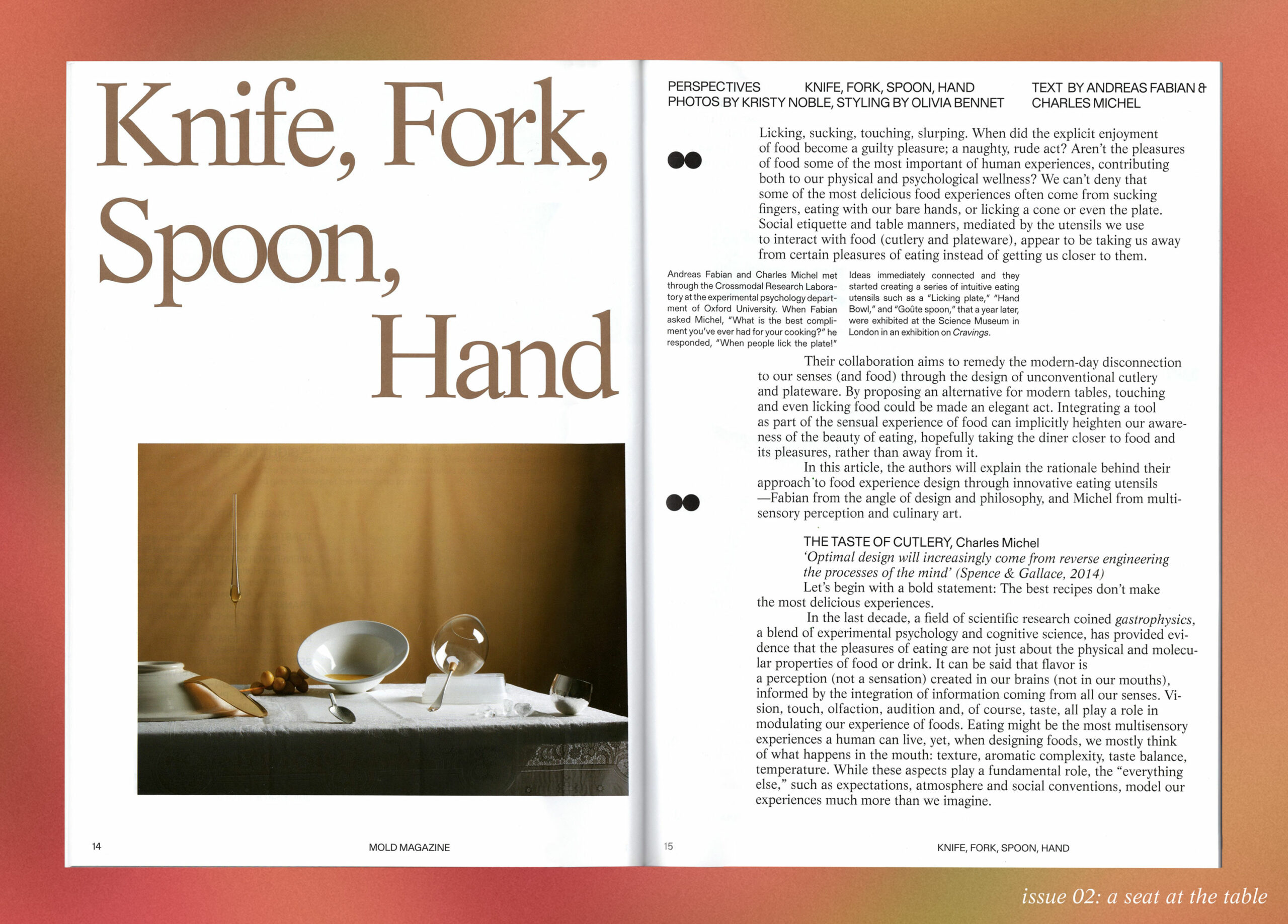

Goute spoon by Michel/Fabian. Photo by Kristy Noble and styling by Olivia Bennett for MOLD Magazine.

Goute spoon by Michel/Fabian. Photo by Kristy Noble and styling by Olivia Bennett for MOLD Magazine.

For example, in an experiment we conducted in 2015, we served diners at a large dinner the same food, but half of them with banquet cutlery, and the others canteen cutlery. Unaware of the manipulation, we asked diners to rate how flavorful they found the food, how beautifully presented and plated they thought it was, and how much they would pay for it. Surprisingly, ratings were significantly higher from customers given the banquet cutlery. People were willing to pay 15% more for their food, found it to be more delicious, and found the presentation more beautiful.

But why? The shape and overall design of the two different cutlery sets were very similar. The weight of the banquet cutlery, however, was three times heavier than the cheaper counterpart.

This experiment, published in Flavour Journal together with Professor Charles Spence and Carlos Velasco, is just one example of the dramatic changes that cutlery can affect on the eating experience, or may we say, on the flavor of food. Other research from Spence’s Crossmodal Research Laboratory at the University of Oxford has shown that the color of the cutlery can affect how sweet or salty food is perceived to be. The same goes for plate color. Plate size has been shown to change how much we eat, and how holding a plate in your hand can change how fast and how much you end up eating.

Despite this evidence, food designers at large seem mostly concerned about products, recipes and the art of cooking—which is a noble endeavor—but fail to acknowledge the complexity of eating psychology, and the importance of the “everything else.” Thinking about cutlery to enhance pleasure, guide healthier consumption and even model the emotional content of eating, is probably one of the most effective ways to make diners engage in different ways—whether that’s via changing the social dynamics at the table, or implicitly guiding them towards a more attentive consumption behavior.

We should also remember that many humans today eat with their bare hands. Yet restaurants and canteens—key spaces that shape our everyday well-being—impose cumbersome lumps of metal that hundreds of people may have put in their mouths. And if not metal cutlery, diners are offered single-use plastic objects that add to modern society’s mindless waste. But ask yourself this: what is the most successful restaurant brand on earth, the one that feeds more people than any other?

Across towns and cities worldwide, McDonald’s serves millions of meals each day to be eaten… with hands. No cutlery. Is that part of their success? Could their success be owed to the fact that they are one of the few restaurants where adults (and children) can indulge by being allowed to eat food with bare hands? Another example of a world-famous staple that should be eaten with hands is pizza. Ask an Italian how it should be consumed; always with hands! There is even an etiquette on how to slice the pizza, how to hold it elegantly and bring it to the mouth—those who learnt the Italian way know that the pizza’s juices hold better this way, and each morsel is much more delicious than they could ever be if the pizza were to be eaten with cutlery.

By now, I should have convinced you that the role of cutlery in modern life and social etiquette should at least be put in perspective. Of all the technologies we interact with every day, one of the most intimate (and one of the few we put inside our bodies, apart from the toothbrush) has barely made any evolution in the last few centuries. Innovations in cutlery are made mostly with visual considerations in mind. In our opinion, visual beauty should result from functionality, gesture and the material used to achieve these.

Today, the design of the tactile experience of food is pretty much limited to in-mouth stimulation despite the fact that our hands and lips are two parts of the skin organ that represent the most significant amount of somatosensory cortex in the human brain. And hands and lips could be the focus where cutlery and plateware design could be invited to bring an interesting addition to the multisensory world of eating. Innovating in the way we approach the act of eating could also have a fundamental impact on our food intake and health while maximizing the amount of pleasure we get from eating.