This story is part of MOLD Magazine: Issue 02, A Seat at the Table. Order your limited edition issue here.

A group of travelers arrives in a village hungry and empty-handed, begins the stone soup folk tale that dates back to the 16th century. Told across Europe, from Ukraine to Portugal, the story goes that the wary villagers are reluctant to share their food, so the travellers put a large stone in a pot full of water and put it on the fire. Curious, villagers begin to inquire about what they are cooking. A delicious soup, the travelers explain. If only they had a touch more garnish and seasoning to enhance the flavor, it would be perfect. Intrigued, villagers begin to part with a carrot here, an onion there. Soon the soup is rich and nutritious, whereupon the stone is removed, and the soup is shared with all.

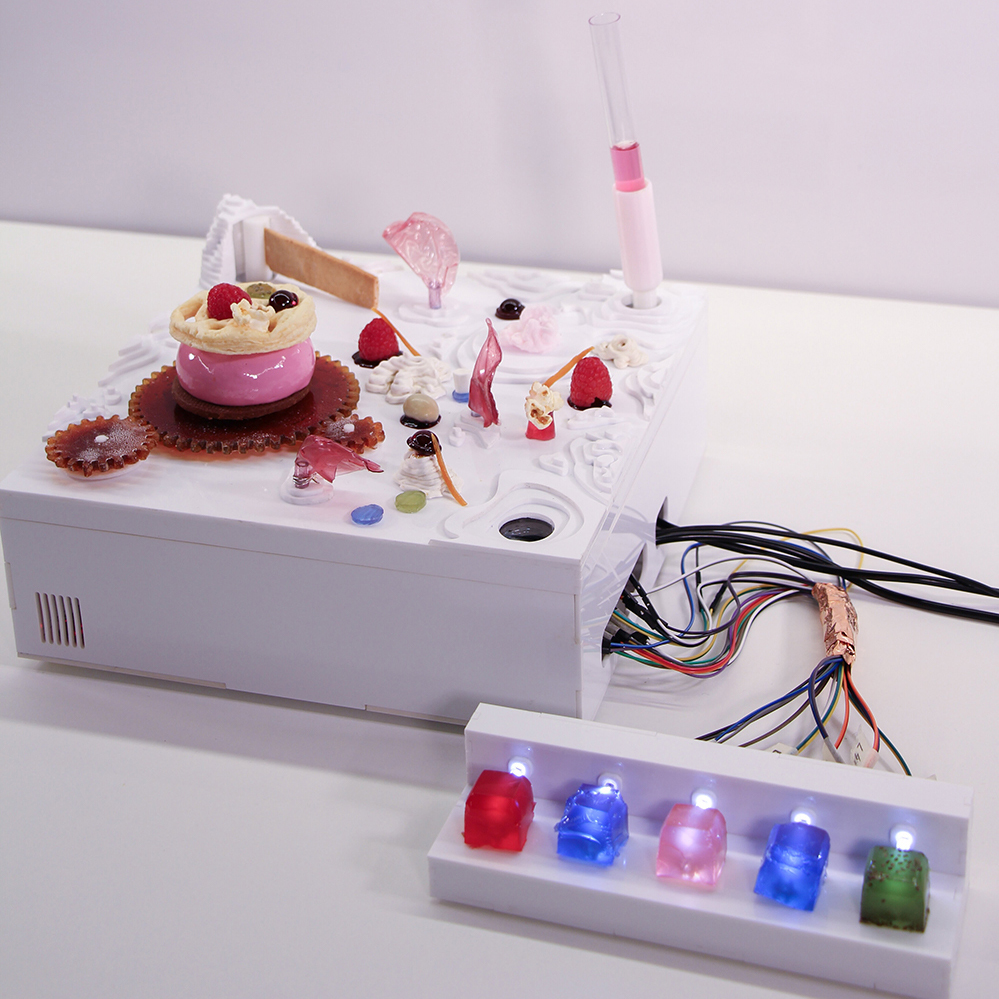

While the travellers might have duped the villagers into sharing their food, all’s well that ends well. This sleight of hand is also the intention behind Marije Vogelzang’s Volumes—she hopes to trick us into eating less. Commissioned by the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg for the Food Revolution 5.0 exhibition, Volumes is a series of peculiar-looking objects that can be added to one’s plate to make it look fuller.

“We have the tendency to overeat and are visually misled by large plates and wide drinking glasses,” explains the eating designer who, since 2015, has headed the Food Non Food department at Design Academy Eindhoven. “By adding Volumes to your plate, your brain will register more food than there actually is. Your stomach can’t count. Your brain will tell your stomach it had enough.”

As in the folk tale, the Volumes are, in fact, garden-variety stones, covered in food-safe heat-resistant silicone. The thermal mass of the rocks also serves to keep food warm or cold for longer, encouraging slower eating. In creating an aesthetic for these provocative food prosthetics, Vogelzang neither wanted Volumes to look like part of the dinnerware, nor like actual food. The choice of unusual colors and forms are in service to the illusion—the brain reads each “Volume” as distinct from the plate itself and definitively inedible once a diner consumes the food around it.

“Most of us don’t overeat because we’re hungry,” explains the website of nutritional sociologist Brian Wansink, a pioneer of the concept of ‘mindless eating’ that inspired Vogelzang. “We overeat because of family and friends, packages and plates, names and numbers, labels and lights, colors and candles, shapes and smells, distractions and distances, cupboards and containers.” Although the sociologist, who serves as the director of the Cornell University Food and Brand Lab, has recently come under fire for data irregularities, the current scrutiny of Wansink’s work does not mean the findings are incorrect.

As the centuries-old folk tale shows, a lot of the principles of mindless eating are plain common sense. Perhaps this is where food design’s significance lies: in taking the field beyond statistical analysis to creative and experiential fruition.