Drawn from my pilgrimage home to Fuzhou, China, where mandarin trees nested in my grandfather’s garden and an altar stood in love to my grandmother, ‘gifts from the mandarin tree’ is a poetic speculation about how cutlery can offer rituals of digesting and processing life and death, past and future closer to one’s table and palate. Mandarins are tender and sweeter than the common orange and evolved from regions like that of South China. Known to grow in tropical and subtropical regions, this fruit has been adopted by several cultures as a spice, medicine, and tool for digestion.

Words and images courtesy of Mei Zheng.

PROJECT OVERVIEW

Raised by quiet love languages, I’m interested in the complexities of food through sensory experiences and spirituality as forms of rituals. In an exploration to understand a decade in the making, I created tactile cutlery as tools to remember and speculate (new) modes for digesting and processing life and death.

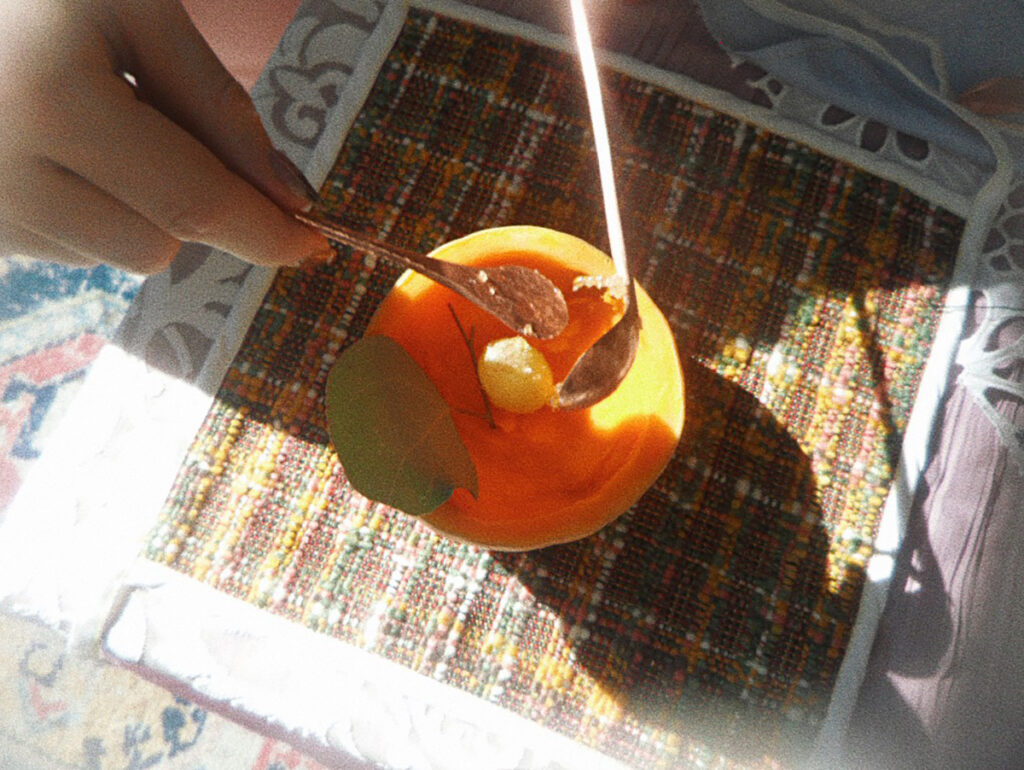

‘gifts from the mandarin tree’ is an ongoing project starting winter of 2023, influenced by my pilgrimage back to Fuzhou, China in 2013. The cutlery inspired by the mandarin’s pebbled soft skin and made with copper forged to a rosy orange, is textured with a chasing hammer. An acid wash removes oxidation after heating the copper and is food-safe once washed. This set of three utensils represents a lineage of generations and stages of growth. It is brought to an altar composed of citrus-baked salts, candied Tanghulu fruits, and preserved citrus in an ongoing process of decay. The citric acid slowly digests the copper as one slowly consumes from its surface.

How can the process of creating cutlery deepen our ties to rituals, inheritance, and memories that honor both life and death?

In a week, I will return to Connecticut to enjoy fruits with my grandfather before he goes back home to Fuzhou, China. Whenever I’m with him, I remember his words, “Here eat this”, but that’s changed with time. Now, his diet has changed, and he can’t eat as much as he once could–so I ask.

A decade ago, I went with my brother in August to visit him. The same phrase, “Here eat this”. I hear my grandpa as he enters the living room, holding out my arms with my hands cupped–catching warm sun-kissed mandarins harvested freshly from his garden. I notice that there are mandarins, polished–sat closely by a framed picture of my grandmother. At a faucet, running water flows against the creases of my skin. I hear him light an incense held in gentle bows of the body–up—down–up–down–smoke whispers through the air.

The sacred site of the Xichan temple is a Buddhist temple located on the slope of Mount Yi in Fuzhou, China. During my pilgrimage, my grandfather took us to visit and perform the ritual of incense burning as he often does for the passing of our grandmother. The smoke waivers, and then sits as our bodies ease from bowing to stillness. These utensils replicate the manners through gestures of bowing, and long stems made to rely on balance or rather a way of sensory processing/interface. The incense is placed into a bronze censer and in its last breaths, our eyes are closed–we wait. I wonder what inheriting death looks like in the passing of generations, like that of the copper utensils eroding, or the bronze censer walls building patina through oxidation. It becomes an artifact of one’s body performing a ritual, a byproduct of digestion, and an act of labor met with love.

The power of these moments was slowness, an experience that can’t be reproduced and rather felt. This fruit–this mandarin tree–is kept alive and the ritual makes for honoring those that have passed with these gifts of prayer–a way of processing life and death for oneself. It is passed down tradition through embodiment, as food is always at the altar–how can it be more integral so we don’t forget?

DESIGN PROCESS

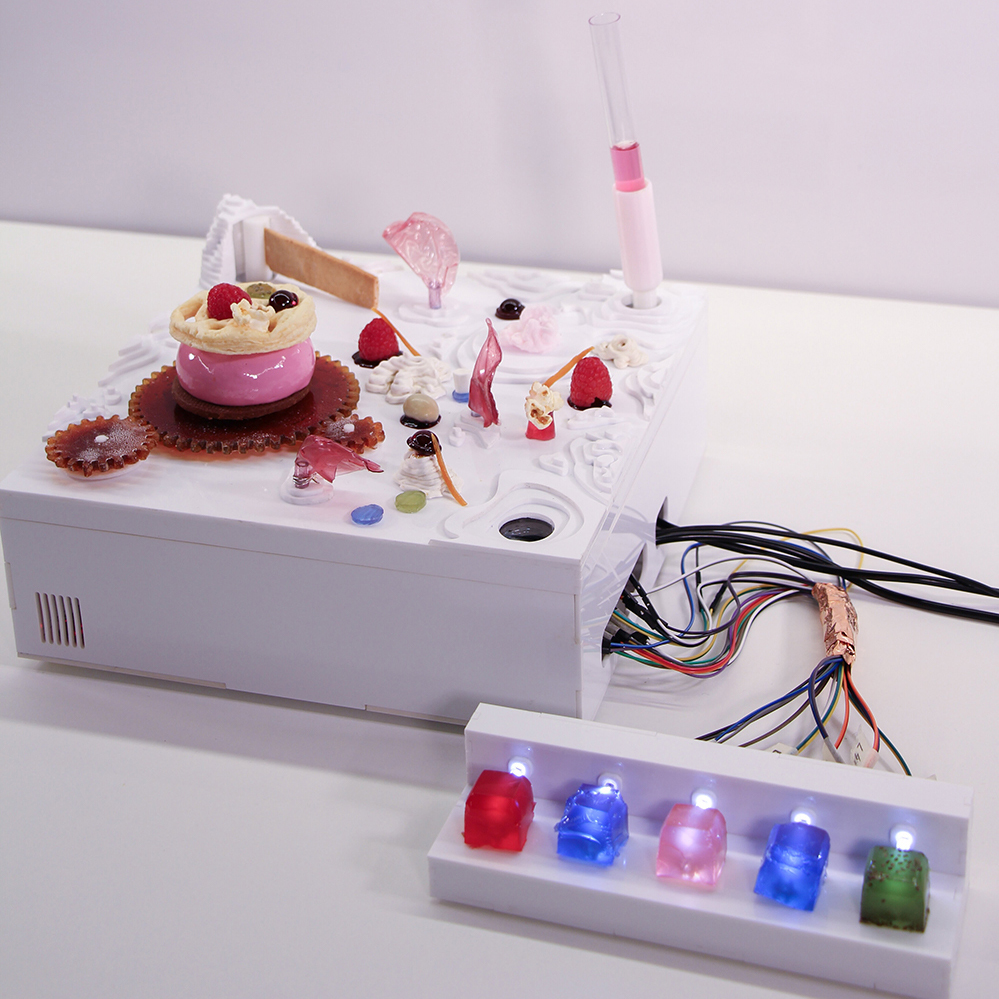

This project was imagined with the support of many and the class, “Ambiguous Implements”, taught by Rachael Colley, in collaboration between Steinbeisser and RISD’s Jewelry & Metalsmithing Department. In this studio, we interrogated the ritual of the table, to challenge the conventions and traditions of food consumption by deconstructing and reconstructing eating implements. We also looked at potential ways of creating biomaterials and recipes from waste streams in our experiences with consumption patterns and local foodways.

The process began with a longing to uncover knowledge kept about my grandmother’s passing, seeing family photos of our garden, and my pilgrimage to Fuzhou. I was curious about the assimilated domestic space of the American home, and why a framed picture of my grandmother existed in our living space never to be looked upon by my parents. When I visited China in 2013, I saw that there was an elaborate ritual with food, movement, and prayer to honor those that have passed. I learned this through my grandfather and our Mandarin tree.

These memories are carried on by the mandarin tree, a physical form of vital generational knowledge. To be passed on for generations to come, it’s important to understand how one cares, loves, and remembers this kind of ritual in itself. This set of copper cutlery represents a lineage in relation to passing of knowledge. The elongated stems instinctively allows the performance of this body-bowing ritual – in a sense to uncover, gesture, and digest decaying citrus-infused salts, candied Tanghulu, and preserved citrus of the altar. Salt production through sun exposure influences the Fujian coastal cuisine we consume daily; salts are also commonly used to preserve and control the fermentation of foods. Tanghulu is a traditional Northern Chinese snack of the Song Dynasty consisting of a thin, glistening sugar shell coating Chinese hawthorn or fresh fruits and is commonly associated with celebrations and medicine. In this project, I explore the tastes of the region through the five tastes: sweet, salty, sour, bitter, and umami. The citrus becomes bodily undergoing processes of fermentation and preservation and its acid slowly digests the copper as one consumes from its surface.

SHAPING THE FUTURE OF FOOD

This project is speculating ways to remember through (new) modes of digesting and processing foods. In reflection of hyper-local food systems and integration of crucial generational knowledge towards cultural and spiritual rituals, the power of cutlery can inform and strengthen these ties to memory that honors both life and death. Table to altar, altar to table.

‘gifts from the mandarin tree’ is not just a cutlery set. It’s about love, care, and labor. Holding onto tradition is knowing embodied ways of moving one’s body and digestion, whether physical or spiritual. These artifacts hope to strengthen knowledge passed down generations to come.

ABOUT THE PRACTICE

Mei Zheng is a Chinese-American designer, baker, and educator born in New York City and based in Providence, RI. They are working towards their MA in Teaching + Learning Art and Design Education at the Rhode Island School of Design (2024) and completed their BFA in Industrial Design with double minors in Nature Sustainability and Scientific Inquiry Studies at the Rhode Island School of Design (2023). Their practice involves public-facing design often through the perspective of food and its soft powers of storytelling, community engagement, & education. Mei’s practice is heavily influenced by social frameworks that help us collectively imagine the many desired spaces of cooperative collaboration, love, and care. Mei has been an exhibition designer and speaker of Eating in Edo at the RISD Museum in discussing what food and memory mean to a collective body and as Co-Curator featured in Ambiguous Implements, an experimental dinner with Steinbeisser and RISD’s Jewelry and Metalsmithing Department. They want to continue co-creating spaces of transformation, believing as designers, we become educators. As educators, we become learners. As learners, we become storytellers. We transform and are transformed.