This story is part of MOLD Magazine 02: A Seat at the Table, exploring how tableware and furniture can shape new dining rituals. Order your copy of the magazine here.

A social etiquette has emerged around the consumption of food in the West that requires the use of a set of tools we refer to as cutlery; e.g. a knife for cutting and a fork and spoon to transport foods from the eating vessel to the mouth. We are socially and culturally guided to learn their use as a function of subtle changes in their size, shape and material, and develop a set of manners that often depend more on social approval, rather than on what enhances the pleasure of food, ultimately creating a distance between the food and us.

Cutlery has become an extension of our hands in the act of eating, an essential part of our daily experiences. Cutlery has evolved with our eating habits and the development of technologies: the ‘toolness’ of hands has been slowly externalized in the form of utensils that allow us to bring food to the mouth.

By its very nature, tableware requires handling and use, which raises issues of social interaction, manners and etiquette. Animals eat their food without ceremony, often bloodily. Humans prepare their food carefully, and their eating is refined and ordered, according to cultural codes and social precedence.

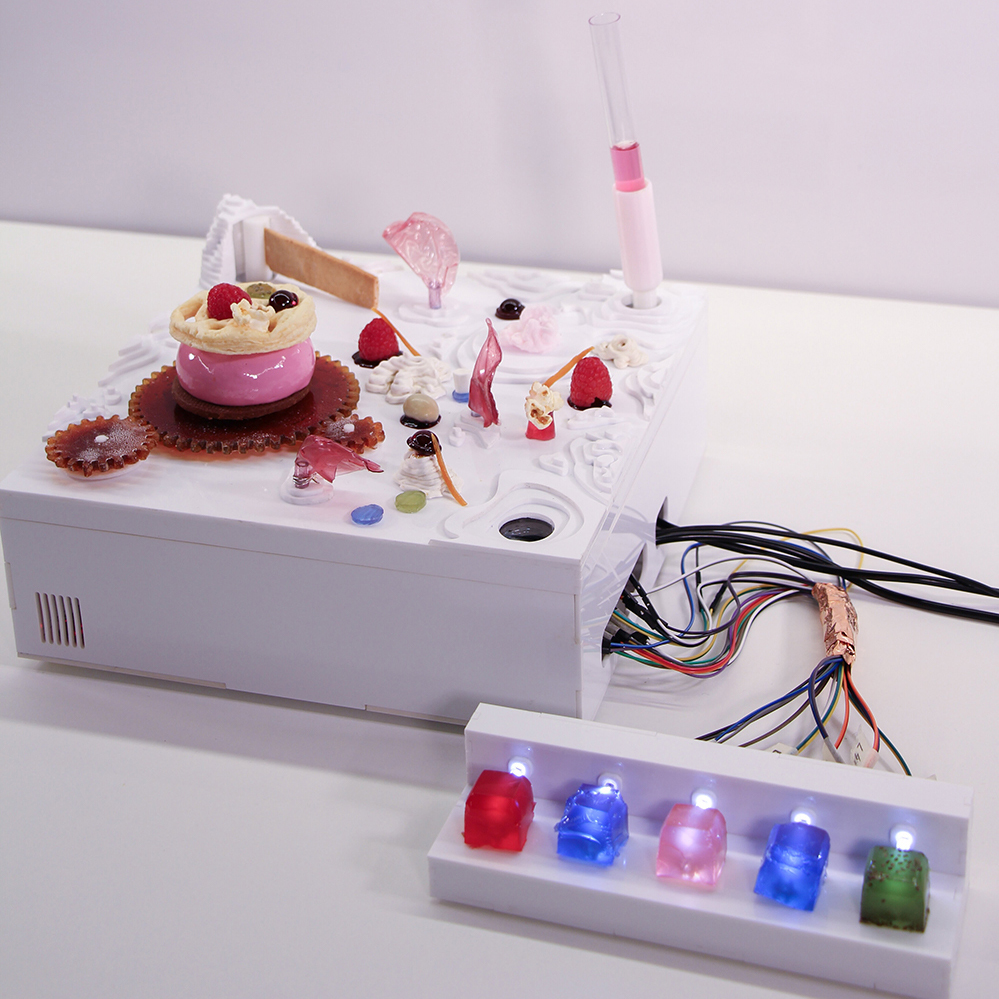

Hand bowl by Michel/Fabian

Hand bowl by Michel/Fabian

The sociologist Norbert Elias sees the development of table manners in the broader context of civilization. Of particular interest is the connection he draws between table manners and language: “… there being people so delicate that they would not wish to eat soup in which you dipped it (the spoon) after putting it into your mouth. This délicatesse, this sensibility and a highly developed feeling for what was embarrassing, was at first a distinguishing feature of small courtly circles, then of court society as a whole. This applies to language in exactly the same way as to our eating habits.”

Elias makes clear the way in which, historically, people came to pay the same attention to eating manners as to their way of speaking and writing. Would we nowadays also draw a connection between ‘délicatesse’ (or language) and manners when observing the booming industry of good quality street food (and fast food) where people eat with their fingers, holding bowls and plates in their hands? Might this trend, in the long run, also influence tableware design and how we eat at the table?

It has been suggested that in the earliest stages, the need for restraint and codified manners was driven by courtly pressures during the reign of Louis XIV and his predecessors at the French court. The introduction of mirrors in the 17th century and the precedent set by the court at the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles, may have played a key role in the process of refining our (table) manners. Mirrors enhance our social awareness by allowing us to see ourselves as others see us—separating body and mind. Furthermore, it is interesting to observe how between the 18th and 19th centuries, European aristocracy, followed by the bourgeoisie, started to serve food in a new way. The so-called ‘French style’ was replaced by the ‘Russian style’ of serving food: as still common in most restaurants, individual plates of food were served to individual diners instead of a communal dish shared by guests. This clearly represents a shift towards individualism.

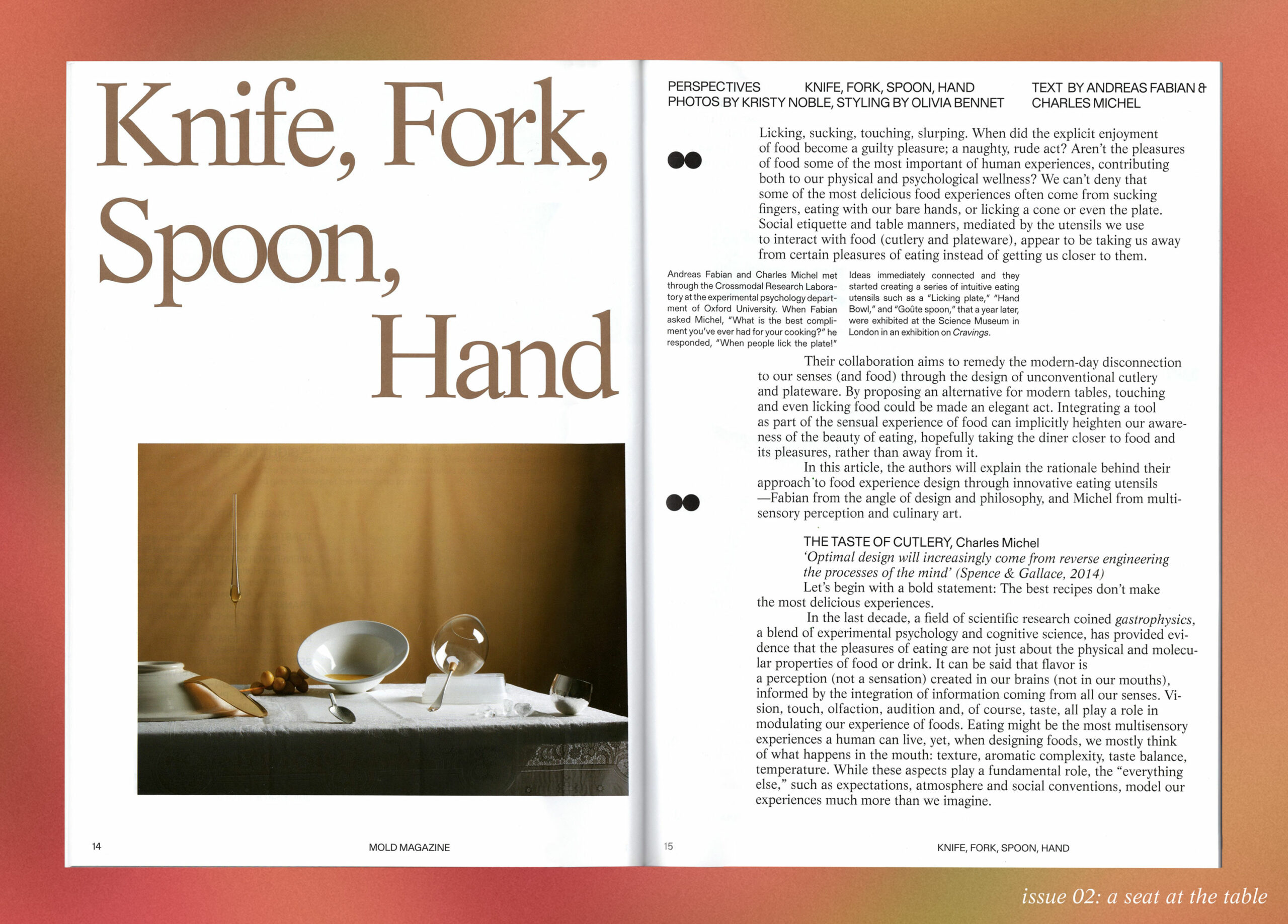

Licking Plate by Michel/Fabian. Photo by Kristy Noble and styling by Olivia Bennett for MOLD Magazine.

Licking Plate by Michel/Fabian. Photo by Kristy Noble and styling by Olivia Bennett for MOLD Magazine.

The very short distance from “the hand to the mouth” is not only a measure of manners but of how those manners are a metaphor for the history of civilization—representing our cultural values in a particular civilization in time. Our culturally determined table manners influence the design of cutlery, and the design of our cutlery, in turn, influences our table manners and etiquette. For example, the introduction of the fork as an eating utensil in the 17th century became a ‘fashion statement’ and then became widely popular.

An indication of how much cutlery has become woven into the fabric of our culture is to examine how it has crept into language: many common sayings relate to cutlery, often to the spoon, illustrating its particular importance. For instance, The Who, in their 1966 song “Substitute,” parodied the expression ‘born with a silver spoon’ with “I was born with a plastic spoon in my mouth,” relating material (silver/plastic) to status (high/low).

Regardless of the material used to make it, when we eat with a spoon we are using an intensely intimate instrument: aside from feeling it in our mouths and on our lips, it’s worth reminding ourselves that we often use spoons that others have previously had in their mouths. Artist Richard Wentworth described something of this intimate and extraordinary phenomenon, albeit discussing plates: “The strangest thing about plates is that when you sit down to eat you get your own, but the moment you finish it’s somebody else’s. Plates operate in a complex world of manners, sharedness and separation—a public/private thing, enormously widely experienced. This makes them very special.”

Tableware exists within a highly complex field in terms of how it is experienced and how it generates meaning. For example, the way we handle the spoon between thumb and fingers nowadays is defined by manners and etiquette. Handling a spoon instinctively (as a child would) now seems inappropriate and has become culturally determined. In this sense, the spoon cannot be defined only as an eating utensil but must also be reckoned as an instrument of social distinction. Furthermore, a small drop of soup on the bottom of our spoon might cause our entire body language to shift lest it falls and leaves a mark on a table cloth and, more significantly, a stain on our social reputation.

The form of cutlery might change over time depending on technology, fashion and imagination, but its function goes far beyond its purely practical purpose of bringing food to the mouth. Despite the omnipresence of eating tools across cultures, it seems that in recent centuries they have been designed with mainly aesthetic, ergonomic and functional purposes, according to the rituals and social manners of the table.

How interesting could it be to think and design the opposite way—designing social manners according to innovative eating implements and technologies?