This story is part of MOLD Magazine: Issue 04, Designing for the Senses. Pre-Order your limited edition issue here.

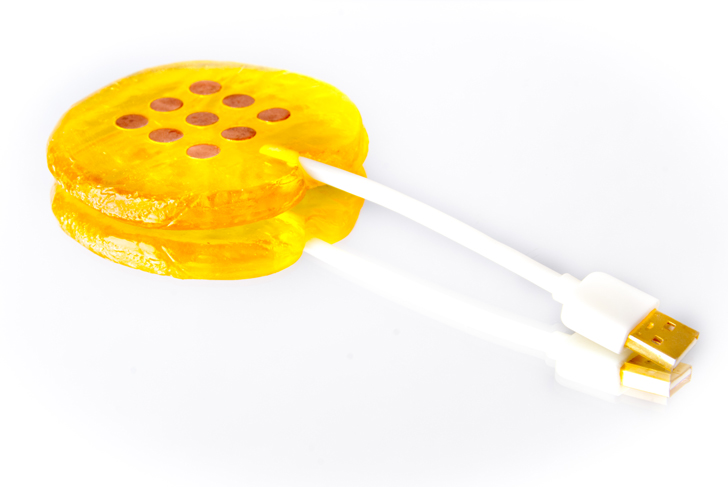

This February marked a weird gap in nostalgia: following the bankruptcy of storied confectionery company Necco, the Spangler Candy Company took over the production of Sweethearts—the iconic edible love notes—but not in time for Valentine’s Day. While they’ll be back on shelves next year, in the meantime, Erika Marthins has gone one better: the Copenhagen-based food designer created a lollipop inscribed with a secret message that is invisible to the naked eye but appears when one shines a light on the treat.

Lumière Sucrée is one of three interactive desserts in Marthins’s project “Déguster l’augmenté,” her final diploma project for the Interaction Design program at the Swiss design academy ÉCAL, with which she launched Augmented Food Studio. Realized with the help of collaborators in cuisine (Chef Fabien Pairon), robotics (engineer Jun Shintake) and industry (RayForm), the culinary/visual provocation is documented in a video that made blog rounds when it was published in late 2017.

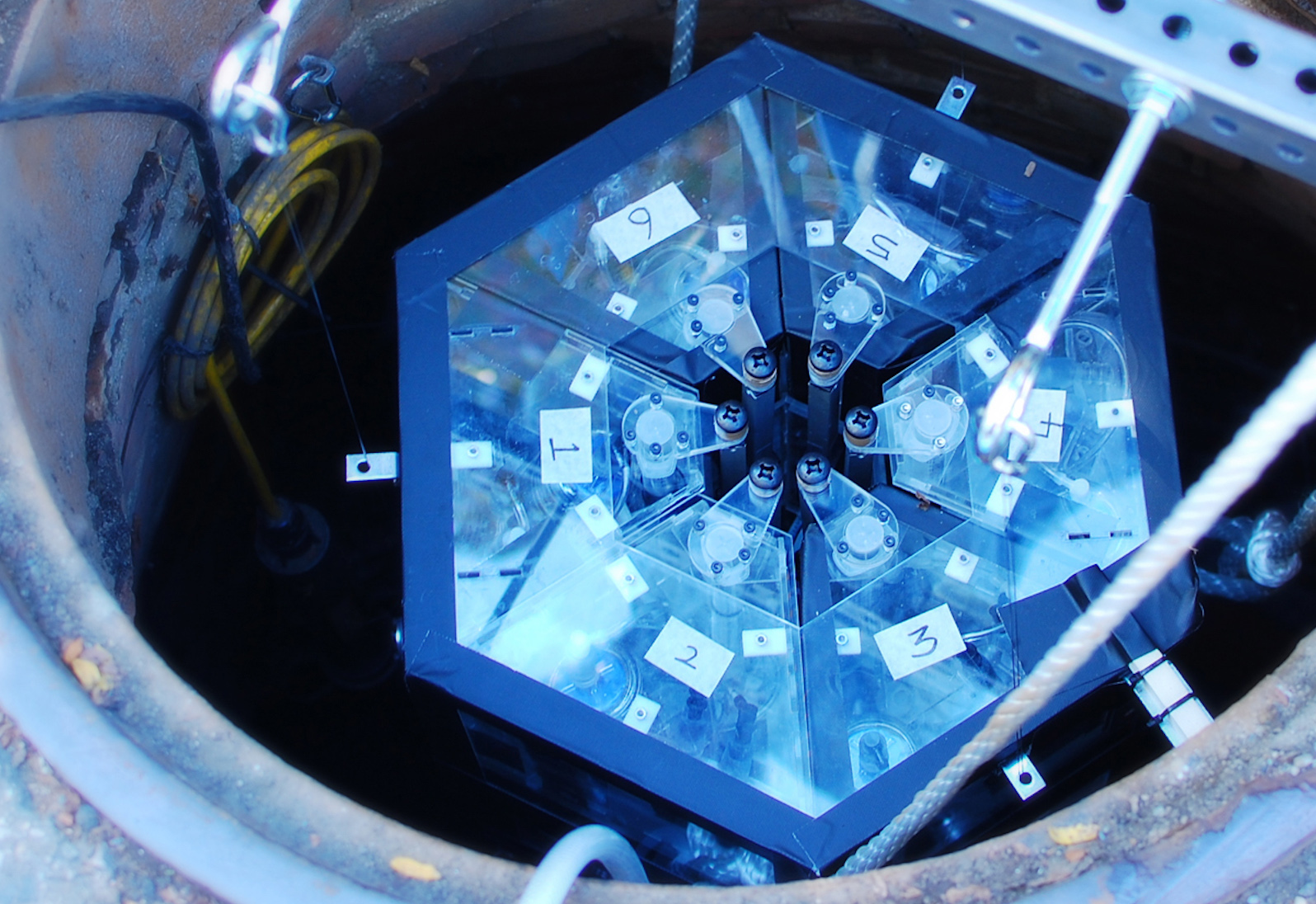

Besides Lumière Sucrée, Marthins has created a record that melts in your mouth and not on your turntable: “The chocolate disk is about listening to your desserts. [You can] have a small conversation with your dessert, and then you can actually eat it.” But it is the third one, Dessert à l’Air, that prompted headlines such as, “Would You Eat a Robot?” In principle, soft robotics entails a flexible material—i.e. gelatin—embedded with pockets of air, which can be inflated to emulate movement (picture a balloon bulging as you squeeze it); in practice, it’s a petri-dish-sized purple amoeba-like structure that wriggles in “a small performance on your plate, almost like a dance.”

Taken together, “Déguster l’augmenté” offers three answers to a bigger rhetorical question: if technology can become invisible, what if we can eat it? Indeed, Marthins’s notion of augmented food is as much a rejection of augmented reality as it is a radical expansion of it, proposing that “food” is not merely a subset of “reality”—a surface on which to project a superficial layer of data—but rather that “augmented” connotes a wide horizon of sensory dimensions, further than the eye can see.

Moreover, Marthins sees her work as a remedy to our contemporary gadget-addled alienation. “We’re scared of the unknown, so when we don’t understand technology, we don’t know where to begin,” she says, citing Apple products as a case where technology is hidden to the effect that “it’s just supposed to work.” Augmented Food, on the other hand, “[integrates] technology into an edible material so that you’re actually eating technology.”

Of course, it’s one thing to “[perceive] food as a design material”; it’s another thing entirely to suggest that we can gain a better understanding of, say, robotics if we literally consume it. After all, it’s not a matter of comparing apples and oranges but rather iPhones and vinyl, and the 26-year-old designer has a tendency to speak of technology as a single, monolithic entity, despite the fact that Augmented Food chops it into digestible morsels.

Take “Taste Lab,” another research project by Augmented Food Studio (with Stella Speziali, Juan Garcia, and BeAnotherLab). Marthins describes it as an attempt to “mix up and hack the different senses,” a virtual reality twist on the old-fashioned blind taste test, leading her to conclude that “[most people don’t] trust the textures, the flavors, and the smell that much—you eat with your eyes.” Hence, the paradox of her work: predicated as it is on ingestion as the ultimate gesture of designable interaction, these augmented foodstuffs can only truly be experienced in the flesh, yet as a concept it lives in the cloud, propagating digitally, through images and videos.

To that point, Marthins relates that she is as interested in the cultural dimensions of food as she is in technology. “A lot of what we eat is based on memories, so we’re kind of attracted to [certain] flavors and textures because it reminds us of what our grandmother was cooking for us when we were kids.” Those flavors and textures may not change all that much in the future, but we may well be getting to grandma’s house by self-driving car; the ingredients will be delivered by drone; a chatbot will fact-check the banter; and the family photos will be as rich in metadata as the meal is in calories. Augmented Food fills in the gap between memory and data—a tantalizing taste of near-future nostalgia.