This story is part of MOLD Magazine: Issue 04, Designing for the Senses. Pre-Order your limited edition issue here.

Throughout history, humans have used technology to expand their perception system. As we design more intricate methods to push our bodily limits, we’ve continued to create more intelligent tools that sense for us and tell us about what we cannot see, smell or taste. Telescopes and microscopes are examples of instrumentation that extend our visual perception beyond the limits of what the human eye can see. Historically, such tools explore not only the limits of the physical body but also the mind through instrumentations designed for psychology. One of the earlier examples can be found in the first psychology laboratory in 1879 by Wilhelm Wundt, investigating memory and learning, the mental representation of time, visual and auditory perception, and sensory impressions through chronometers, ergographs, mnemometers, tachistoscopic apparatuses and other tools to explore sensory stimuli. Sensations of Tone, published by Hermann von Helmholtz in 1863, was another demonstration of the human interest in not only the physics of perception but also the desire for creating instruments of sensory creativity. But as we create more intelligent sensors and sensing networks, what do we hope to achieve? What is the experience we wish to create and why?

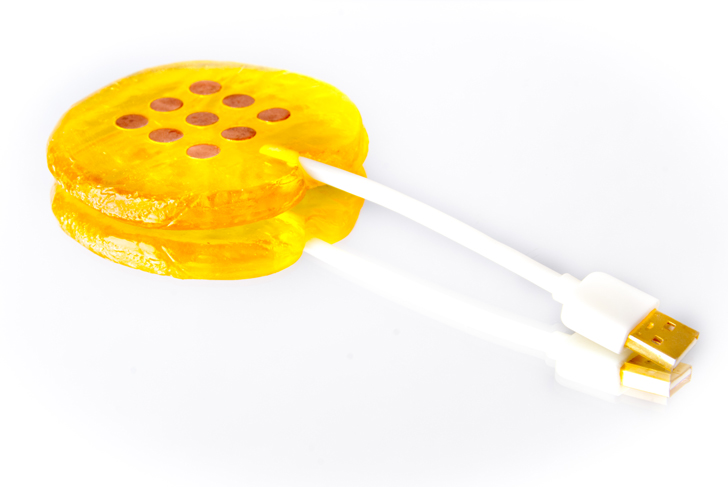

Every human can sense; sensing is breathing, eating, feeling—functioning on a day-to-day basis socially, physically and politically. The act of eating, for instance, asks us to engage with all of our human senses, yet still the way we grow, collect, sort, transport, display, consume and discard food, from production to waste, is supported by networks of information and infrustructures of artificial sensing embedded in machines at every step of the life cycle—our instruments of edible survival.

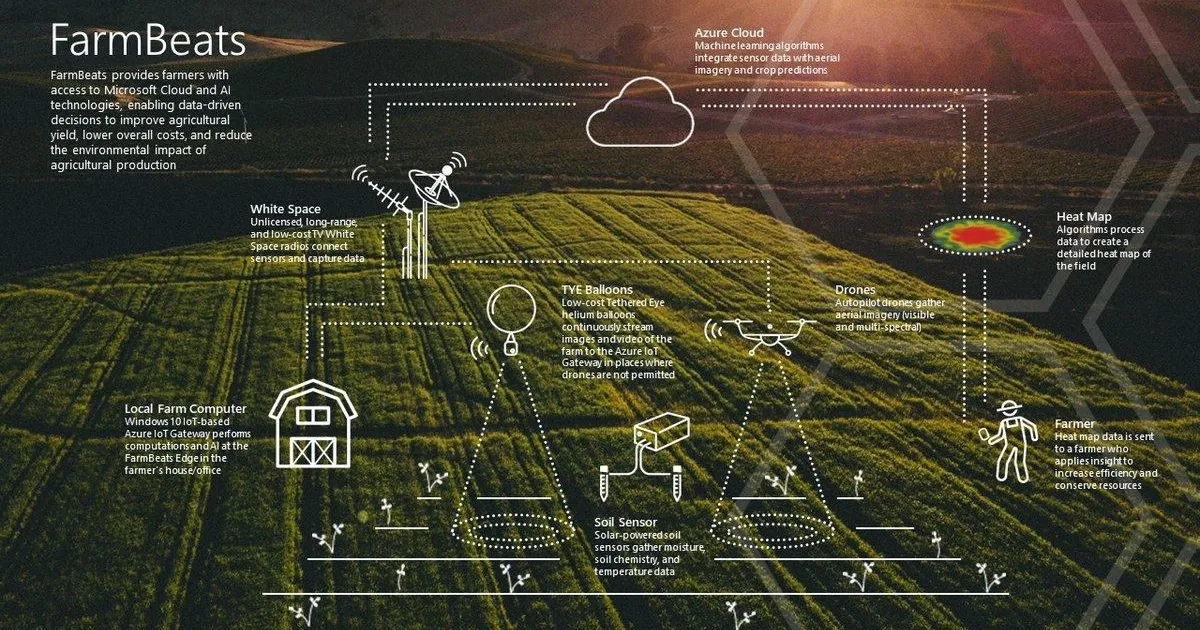

The narratives around emerging and existing technologies are complex and dividing. Sensors are embedded in all aspects of the food system: farming vehicles; mass production facilities for sorting, cutting and mixing; water, air, cooling and heating equipment that ensures the freshness and presentable display of fruits, vegetables and meats during storage; tools that enable exchange at the point of purchase and so on. But outside of food networks, the same sensors are utilized in proximity to our bodies in wearable technologies, networks and topologies of urban and natural landscapes. We are living in the sensor age.

Today, the term sensor readily refers to a module within electronics that, as its name suggests, is bound to the limits of its materials. To challenge this notion of sensing as electronic bits, and to come back to more inclusive thinking around the senses, we can think beyond the material. When considering human perception and sensory systems, the materials of sensing are living and biological. When we think of groups and collective sensing, they could even be considered as cognitive.

So much of how we interact with the world comes back to the ways we create experiences of delight, pain and tolerance through our shared perception. Sensing speaks to us emotionally of texture, olfaction and flavor. It transcends our bodies and frames our ways of experiencing, creating and understanding.

This is a manifesto for sensing: human sensing, biological sensing, hardware and software sensing, multi-species sensing and collective sensing.

The manifesto considers sensing as way of thinking: it is a conceptual framework for thinking about how we design for sensing interactions and experiences created in a world of sensors. It is just a start and will require ongoing dialogue and engagement from diverse groups to push the conversation forward and build awareness about the very systems that define our everyday interactions. It is meant for us in the decades ahead, as we advance scientifically and technologically, to consider design interactions—ecological, social and political—that we might optimize for, collectively.

___

001 MULTITUDES OF SCALE MATTER

Consider the following: a protein sensing a chemical molecule, an organ sensing changes in its surrounding, a human sensing a car in its peripheral vision, citizens of a city sensing an earthquake, organisms on Earth sensing a planetary event. In these examples, we can see that sensing happens at a multitude of scales. Micro to macro, humans to other living and nonliving things, every bit is part of a larger network. As we become more and more enabled through new tools to design systems, we build parallel interactions in different scales.

Termites are interesting organisms, or rather a superorganism, to think about in this plurality. At an individual level they possess basic sensing abilities, but in large groups they are capable of fabricating complex physical structures many times larger than themselves, and they only do this through their collective sensing.

One of the biggest questions of our time is how do we preserve our planet in the long term? What we experience at a perceptual day-to-day level remains a challenge to connect to the planetary and ecological changes beyond our immediate perception, happening at scales and time frames much larger than us. Designing for sensing is not only to acknowledge our own perceived interactions but also the invisible micro and macro.

002 REPRESENTATIONS ARE SKETCHES OF REALITY

Every sensor is optimized to sense a particular thing, and through the lens of that sensor, the world looks a certain way. Imagine a city experienced by a human closing their eyes and smelling and touching its surfaces—in this way the city would be defined through its scents and textures. Alternatively, if we placed a microphone at different locations in the same city, playing back the recorded sound would define a very different sketch of that reality. Now imagine a point cloud of a city, a representation of its topology in points, defined through a sophisticated light detection and ranging sensor.

Many sensing experiences are curated. Behind that experience there is an individual or a group of people who are making decisions on the interactions that comprise it: a selection from a chef who picks the ingredients for dinner, an engineer who optimizes for a particular algorithm, a perfumer who selects the base note for a new scent, or a scientist who modifies a microorganism. All those who create such interactions choose equally what to include and what to leave out. Today it is undeniable that our tools are biased toward certain types of sensing. Our decisions for the types of tools we use and the experiences we create with them represent the world with a point of view. As we build our technologies and interfaces—in the kitchen, on the go, in public spaces—we choose not only the types of sensory interactions to include but also what not to include. We are creating new sketches of reality. Equally so, our tools—cognitive, technological or social—shape our sensory reality of that experience. Just as we wish to share with the world a creation, we should ask what have we left behind.

003 SENSING IS POLITICAL

The desire to embed sensing in all surfaces of life continues to exist. Advancement of more sophisticated sensors begs us to ask the question: who owns it? Who can use it? Who is allowed to sense? Is it accessible? Sensing means more knowledge and to some, more control. Accessibility, ownership and legality become important topics of discussion as they affect many and will define experiences of different groups. When sensors are embedded in public spaces, but owned and controlled by private entities, how is public experience redefined? What kind of regulation and ethical expectations might be designed if our technological tools can affect the biosphere irreversibly? And as technologies advance, what historical knowledge and existing social rituals around senses might we leave behind? Who will be affected? Who will be threatened? Responses to these questions will be widely varied. Sensing is political and we need to talk openly about the multiplicity of desired and undesired futures.

004 SENSORY DESIGN AS RADICAL INTERVENTION

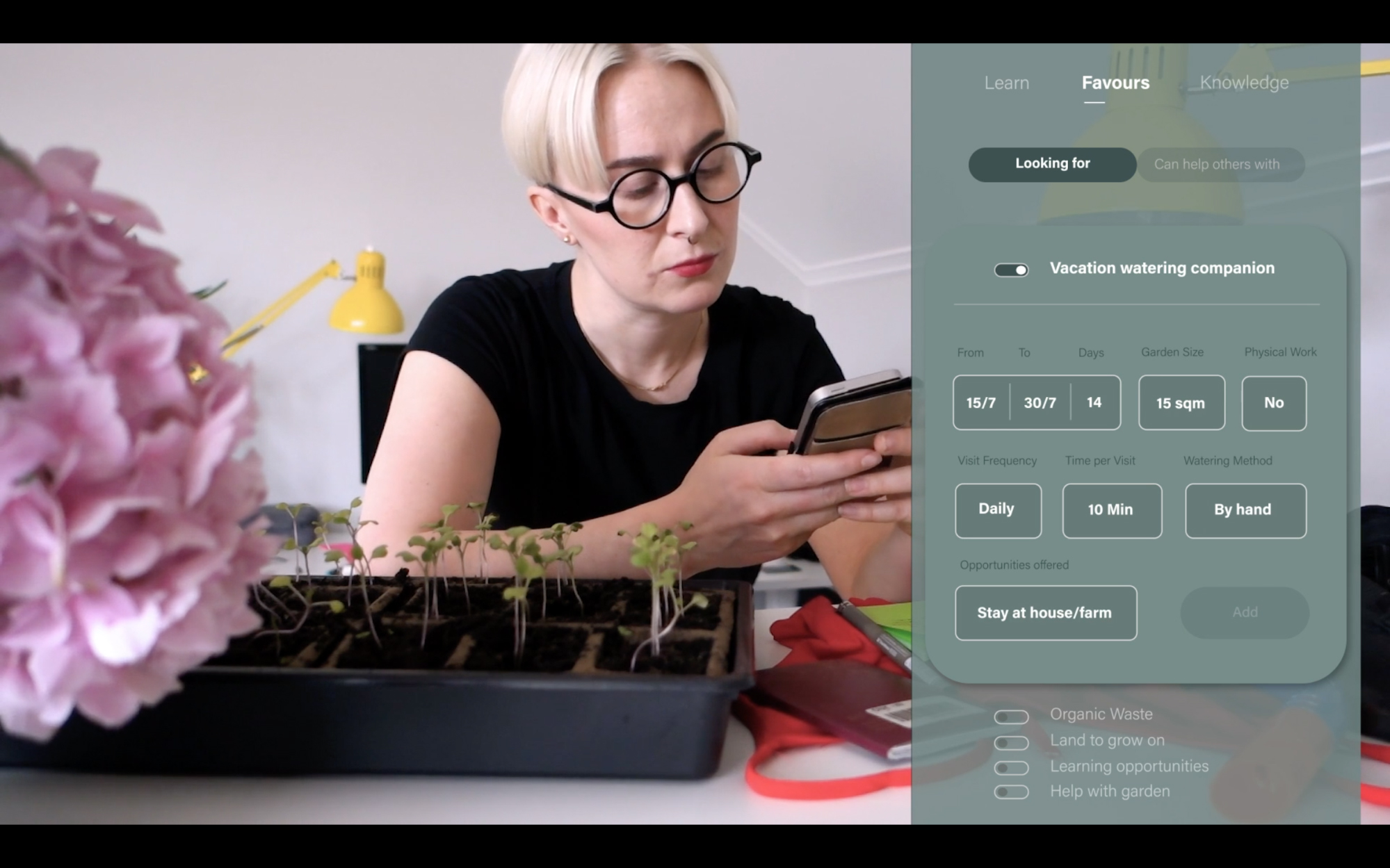

Our current everyday encounters are designed rarely with consideration of sensory inclusion or respect for the senses. Consider the act of scrolling through media content on a smartphone: behind the rapid movements of a 2D image, what we perceive as “an ad” in a fraction of a second and then choose to ignore, thousands of decisions have been made. Despite their newness, our minds have adjusted to smartphones and have mastered the filtering of this virtual encounter. Although at times serendipitous, more often than not we categorize such targeting as noise or even harassment of vision. In the physicality of our urban transit we experience similar immersive interactions that require sensory filtering: the smell of urine in the metro, the jerking motion of the bus as it encounters a pothole, the smell of fat frying from a fast food restaurant around the block. Sensory design interventions can happen at many levels: government (rules and codes), environment (design navigation), transit system (networks and placement), objects (interfaces and affordances), behavior (community, empathy and incentives). To intervene and to design new experiences around senses is to question the thresholds of irritability and desire, boundaries of public and private, and requires decision makers at any level to participate in inclusion to design systems that do not leave sensory experiences unconsidered.

005 SMELL AS AN EDUCATIONAL TOOL

It is undeniable that in our current culture, audio-visual experiences are the primary focus and there is less formal education and awareness around the other senses. One of the more neglected is the sense of smell. The way we perceive the world is through all the senses, but if we focus on smell there are lessons we can learn about the world that we may not pay attention to at first. Smelling is biological and happens at a physical level. But from an experiential level, it is a powerful way to navigate, connect and express. This invisible interaction informs and creates so many of our memories and intimate exchanges throughout time with humans, spaces and objects. While the chemical and perfume industry remind us that much of our smell experiences in the world are designed for consumption, olfaction is a ripe area for a wide variety of creative experiences. Simply by considering the act of smelling and the vocabulary of smell communication we are forced to think from a different frame of reference. Thinking about smell reminds us that there is an invisible world that we might pretend does not exist. Even knowing that there are particles around us at all times, and that every bit of the universe is actually connected, creates a stronger sense of being present in this very physical world. Education and new tools around smell are needed to act as a profound method for cultivating sensory awareness.

006 FROM INDIVIDUAL SENSING TO COLLECTIVE SPECIES

Dinners and gatherings of food in tense, political and awkward situations have always been a great way to bring people together and ease what may seem socially difficult. Despite our status, socioeconomic level, gender or ethnicity, enjoying the taste of food and nourishing the body is shared among humans. At the fundamental level, we are the same, we are human. We need food to survive and air to breathe. Collective sensing is about how we build empathy and support networks inclusively.

Do you see what I see? Can you sense what I sense?

As part of perceiving together, we build collective knowledge of shared experiences. Collective sensing is creating history by acknowledging our common sense. It is reality-building, the way we define truths. But beyond sharing the same experience, it is also accepting that other experiences are valid. Collective sensing asks us to build tolerance for diversity in how we perceive the world. Putting me second, and us first. It is about human diversity, but also about biodiversity. We could say that empathy is an extension of sensing and understanding.

Beyond the human-centered, we ought to consider other species and the earth as a valuable place we share not only with our own diverse human cultures, but with other living things. Collective sensing invites individuals to partake in empathy building. Creative tools and education around the social collective can provide new ways to sense and perceive outside of our narrow notions of perception.

The natural step after sensing collectively is acting for the collective earth.