“When my father was sick, he asked for wonton soup…and not a traditional recipe. He wanted wonton soup from the Chinese restaurant in Vermont that he and his cousins, and then their children, ran. It wasn’t healthy, it wasn’t luxurious, but it was what he knew. And so we talked to his doctors and brought him his soup, with a tear dropper, to the hospital. My mom was convinced that he was happy.”

– Roxie Zhiu, Ph.D. student, Boston

Palliative care doctors and nurses often get requests from family members for “comfort feedings:” permission to feed sick or dying patients foods that deliver enjoyment or hold special meaning. Despite dietary restrictions and choking hazards, comfort feedings are almost always granted, and the hospital works with family to minimally adjust these meals for safety and health concerns. “Food is how we know best to care for one another,” says Jessica Nutik Zitter, a palliative care physician in Oakland, California, “from breast to deathbed.”

Comfort feeding isn’t just something we do in the face of death; we eat for comfort when we’re sick, at family celebrations, or when we’re feeling stressed or lonely. But as we age, other factors such as convenience and popularity become less influential in our food choices; our comfort emerges as a top consideration for how and what we eat. In this article we’ll explore what ‘comfort food’ really means, as well as the different aspects of eating and dining impacted when comfort comes into play.

Understanding food comfort starts by understanding what it means, broadly, to be comfortable. Comfortability indicates feeling at ease in one’s surroundings, and that ease can be physical, emotional, and social. Comfort is as much a sensory perception as it as a mental construct that engages elements of taste, communication, accessibility, and process design. Thus, when we talk about comfort eating, we need to examine the total kitchen.

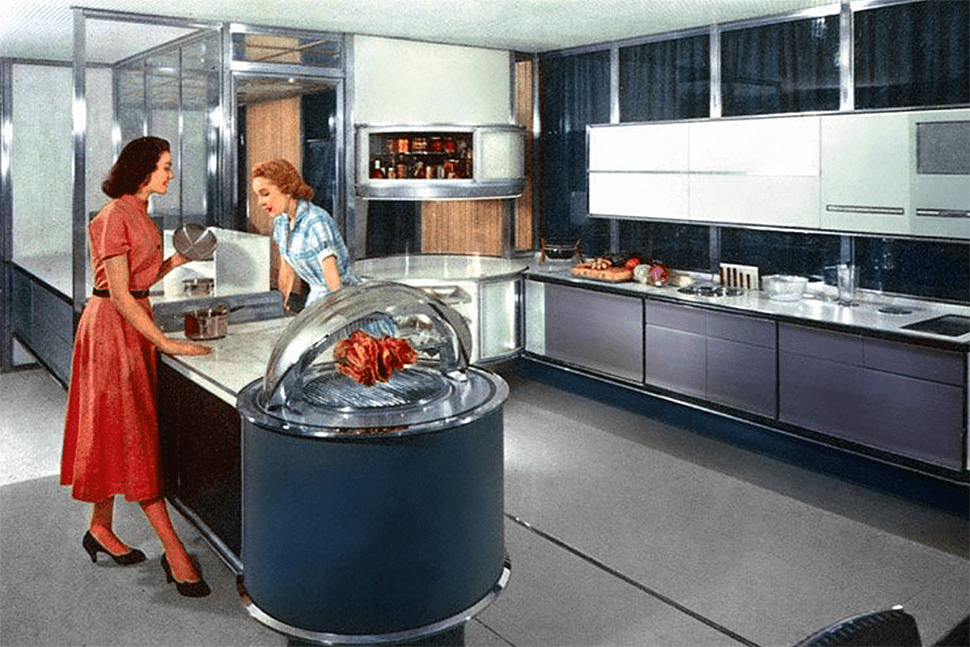

For many, comfortable eating involves easily preparing a meal at home. As we age, several parts of the cooking process need to be adapted for changes in mobility, motor skills, cognition, and memory. [See our feature story on designing food for an aging population.] As more than half of the United States’ households are headed by someone 50 or older, the future of kitchen design is largely a conversation of accessibility for the aging. “As we age, we become less likely to navigate the conditions that shops and manufacturers require of youthful consumers,” says design studio Future Facility, “This puts the aging population in an unfortunate position – abandoned at the exact moment when they need better products, increased assistance and servicing.”

Image courtesy of Future Facility.

Image courtesy of Future Facility.

A comfortable kitchen is visible from all angles, easy to handle (accounting for diminished strength, flexibility, and reach) and modular enough to accommodate mobility devices such as walkers or wheelchairs. Home technology, too, has a place within the comfortable kitchen; it makes comfort a question of personalization and contextual awareness. No matter how minimalist, a smart home is not comfortable is if does not offer a sense of control and security to the end user.

In New Old, an exhibit at the London Design Museum exploring solutions for aging populations, Future Facility explored the technical and material considerations of comfort and eliminated the mental complexity of a digital kitchen. Their Amazin Kitchen concept places basic handles and appliances at chest level and eliminates all-but-essential buttons. Appliances are partitioned to accommodate automatic food and supply deliveries; laundry detergent restocks behind the scenes, as do groceries. Comfort abounds without complication.

Comfort, too, is a motor factor: utensils and cookware must be comfortable to grasp and operate for full kitchen functionality. Utensil comfort plays an outsized role in aging population health; aging persons’ diminished comfort and confidence in the kitchen can lead to anorexia and other severe forms of appetite suppression.

Kitchenware manufacturers such as BUNMO and Senior iCare have popularized adaptive utensils and dishware designed to favor the user’s dominant hand and minimize wrist strain. Single-handed cutting boards, angled spoons, and juice pourers accomodate for challenges such as paralysis and arthritis. Visual cooking, such as measuring, pouring, and placing down items, can also become uncomfortable—encouraging designers like Singapore-based Jexter Lim to design adaptive tableware that accommodates for visual approximation.

Photo courtesy of Jexter Lim.

Photo courtesy of Jexter Lim.

‘Comfort food’ means something different for every eater, but it generally refers to a food that lifts our spirits and is nostalgic in nature. Eating is a psychologically-fraught process: usually ruled by stress (what’s convenient to eat?), fear (should I eat that?), and pressure (is it acceptable to eat this?), comfort food is a pure action of pleasure. It’s also something we allow ourselves more in later life—individuals over 60 eat comfort foods most often, on average three times a week.

There is extensive scientific research on our relationship with comfort foods. They are overwhelmingly cultural, generational, and related to personal nostalgia (black tea is comforting in the U.K.; in the U.S., potato chips rank highest on the list). Despite cultural differences, they seem to have the same general sensory characteristics: soft, sweet, salty, and unctuous. Women cite cold foods (i.e. ice cream) as comforting while men prefer hot meals (i.e. pasta dishes), though that too is likely a by-product of cultural conditioning. Across the board, we reach for them in periods of stress to self-soothe; restaurants are known to add them to their menus during recessions and NASA has explored their effects on astronaut morale.

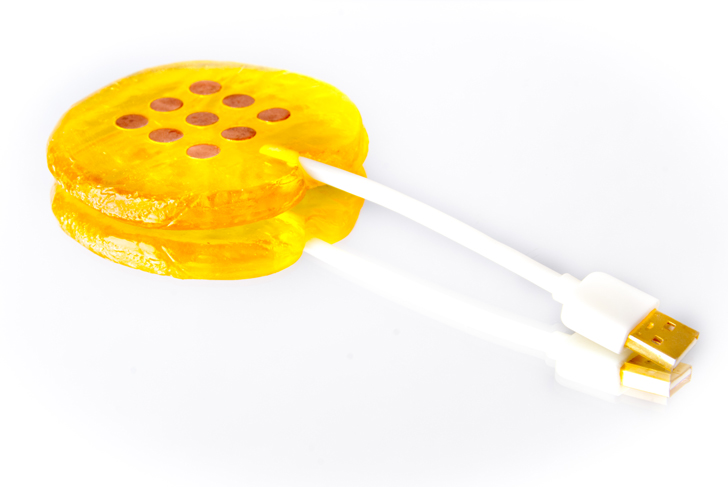

The soft, simply-prepared, and stress-reducing features of comfort foods make them top options for consumption through the last stages of our lives. However at late stages, eating even comfort foods may be inhibited by muscular dysfunction and devices such as feeding tubes. “The medicalization of food deprives the dying,” says Zitter, who encourages her team and the community of palliative care leaders to incorporate comfort feedings and solid, familiar foods as much as possible into patients’ diets. Even if a patient loses their traditional eating relationship with food, they may be able to engage with the other related experiences. Design agency Rodd worked in partnership with olfactory consultant Lizzie Ostrom to create Ode, a small device that releases carefully formulated food fragrances to remind users of comfort foods and pique their appetites. The smell of fish and chips could conjure a family trip to the seaside; as reported, one of the most successful fragrances was that of a cherry Bakewell tart, a traditional British tea cake.

Image courtesy of Rodd.

Image courtesy of Rodd.

Comfort foods are hypothesized to be so stimulating because they remind us of times in our safest spaces, with loved ones. As elderly individuals face staggeringly high levels of loneliness and isolation, it’s time to reestablish a social component into comfort eating. Such was the motivation for Polish designer Magda Sabatowska, who at Central Saint Martins created Social Oven, a cooking kit to help isolated elderly female residents of housing estates socialize with neighbors. By paying for a subscription or bartering with tasks, individuals earn a shared home cooked meal, prepared by their elderly neighbor. Managed as a joint subscription, the model changes a consumer contract (subscribing to a meal kit company) into a social contract.

Image courtesy of Magda Sabatowska.

Image courtesy of Magda Sabatowska.

Comfort is a loaded term, as is the journey towards truly comfortable food. To feel comfortable in our food means many things; it suggests a comfortable kitchen, the comfort of home, and comfort in others. As we think about the role that food plays in our lives, comfort remains an underlying theme: it signifies we first feel safest, and where our palettes ultimately return.