This story is part of MOLD Magazine: Issue 02, A Seat at the Table. Order your limited edition issue here.

Ben Davies wears stylish eyeglasses. “I don’t want them to change when I get older!” the 43-year-old managing director of the United Kingdom-based consumer product design agency Rodd says of their style. It’s a sentiment shared by many design-savvy thinkers as they consider the experience of aging and its effect on their carefully honed aesthetics and lifestyles. “Think of the coolest old person you know: Mick Jagger is not going to settle for some shitty zimmer frame,” jokes Davies. Rodd is one of a growing number of design firms tackling what it means to consider an aging population in its design work. One new project with a “smart wearables” company involves finding a dignified solution to monitoring the location of older loved ones using Bluetooth technology. “It’s quite nice to do this type of future aging product you can imagine that you would want in 20 years,” says Davies.

Rodd’s first foray into aging-centric design came when Design Council, the charity organization that acts as the UK’s government adviser on design, launched a design challenge called Living Well with Dementia in 2011. The Council invited Rodd to take part in the challenge, and the firm began to analyze some sobering statistics surrounding the UK’s rapidly-aging population. One statistic that stood out was that nearly one-third of elderly people in professional care settings are malnourished-attributable to a variety of factors like depression and the loss of chewing and swallowing abilities that cause a loss of interest in eating. Recipients of meal-delivery services and residents of elder care homes often have no connection with food preparation at all, an activity they may have loved in younger years. In turn, severe weight loss can weaken the immune system and increase the risk of falling, setting off a chain reaction that can quickly deprive an elderly person of any remaining independence.

Illustration by Cynthia Alfonso

Illustration by Cynthia Alfonso

To develop a solution, Rodd partnered with olfactory consultant Lizzie Ostrom, best known for her work creating elaborate narratives involving perfume and other scents. The result of the collaboration was Ode, a small device that releases carefully formulated food fragrances before mealtimes, a sort of olfactory alarm clock to help pique the user’s appetite before food is placed in front of them by a caretaker. “Although people become disconnected with fragrance, the science is that one of the parts of the brain that remains functioning [with dementia] is the ability to process fragrance.” In early trials, Rodd saw elderly people that were typically withdrawn and agitated in re-engaging in conversation, telling anecdotes related to their food memories. The smell of fish and chips could conjure a family trip to the seaside; one of the most successful fragrances was that of a cherry Bakewell tart, a traditional British teatime cake. Placed alongside placebo devices in private homes, care facilities and hospital wards, early Arduino prototypes of the device resulted in more than 50 percent of people in the initial research program gaining weight. As Ode was refined, Davies says the team aimed to create a pleasing yet humble industrial design. They avoided any LED indicator lights, which can agitate some dementia patients. “With socially inclusive design, if you can get it right for some extreme-use cases, then you’re really getting the simplest and most elegant solution,” he says. Davies urges designers to imagine their own desires decades from now as they undertake projects for the elderly: “Why would any designer set out to create a product for their future selves that is ugly and undignified and stigmatizing?”

Louise Knoppert’s collection of dining tools includes the “Sponge,” a piece that absorbs liquids that can then be enjoyed by squeezing the implement in the mouth. “Foam” is shaken to create a foam on its textured surface.

Louise Knoppert’s collection of dining tools includes the “Sponge,” a piece that absorbs liquids that can then be enjoyed by squeezing the implement in the mouth. “Foam” is shaken to create a foam on its textured surface.

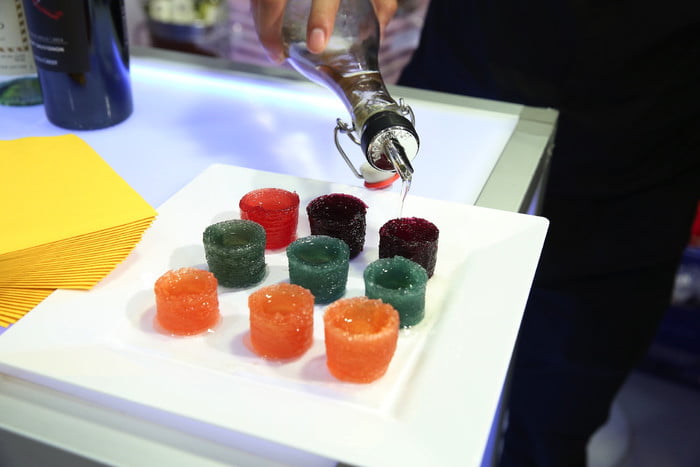

While a product like Ode can enrich the dining experience for those who have lost interest in eating, those who have lost the ability to swallow (a condition called dysphagia) are often completely alienated from the social and experiential aspects of food. When Netherlands-based designer Louise Knoppert learned that approximately 5,000 people in her home country are fed by feeding tubes alone, she began thinking about how to reunite this group with the dining experience. “I can’t imagine life without food and drink and missing out on all the social events that revolve around it,” Knoppert writes on her website. “I want to give these people something back…I want to invite them to the dinner table again.” Her work resulted in Proef, a box of nine slender want-like implements used for creating new types of food experiences that allow users to take part in the flavors, sensations, and actions of others at the dining table without having to swallow or chew. One tool, “Vapor,” uses an ultrasonic atomizer to create smoke from a flavorful liquid; another, “Dip,” allows the user to brush a small amount of pureed food on her lips or tongue.

Louise Knoppert’s collection of dining tools, Proef, helps the elderly and disabled participate in the social and experiential aspects of eating they may be missing.

Louise Knoppert’s collection of dining tools, Proef, helps the elderly and disabled participate in the social and experiential aspects of eating they may be missing.

Morphing food into new forms can help a whole new set of diners stay nourished and engaged with food. In Japan, home to the largest population of people over the age of 65, chefs are learning how to transform classic dishes into purees for those with dysphagia. Kaze no Oto, a restaurant in the suburb of Yokohama, serves older diners items like stir-fry from the standard menu pureed in a food processor for easy swallowing. In other Japanese kitchens and nursing homes, thickening powders and gels allow chefs to reshape purees into forms that more closely resemble familiar foods like filleted fish or chopped vegetables. Other countries are also addressing nutrition concerns among the elderly with new food innovations. In 2015, a project funded by the European Commission explored the use of 3D food printing technology – incorporating customized inputs for macronutrients, texture and density – to create meals for citizens with dysphagia. The resulting meals were a futuristic, albeit fairly appetizing, simulacrum of classic dishes like steak and gravy or fresh peas, and could become the basis of a larger prepared food program in the future.

A meal made from an agar base at a nursing home in Japan. Image by Kentaro Takahashi/The New York Times.

A meal made from an agar base at a nursing home in Japan. Image by Kentaro Takahashi/The New York Times.

New convenience services and apps, too, are becoming crucial players in how older members of society enjoy food. Meal kit delivery companies like Blue Apron in the United States and Denmark’s Aarstiderne allow users to cook with fresh, seasonal ingredients at home even if they can’t drive themselves to the grocery store. Meal Train, a free service that allows users to sign up to prepare meals for a friend or neighbor, can often replace less personalized (and less social) options like Meals on Wheels programs for those in need of support. And as today’s tech-savvy generations grow older, technology will become even more crucial to maintaining independence – imagine using an app like Be My Eyes to connect with a live guide who can help read a menu or food label to someone with a vision impairment, or a platform like Aira, which, with existing smart-glasses technology, could eventually deploy artificial intelligence to help users “see” virtually.

Illustration by Cynthia Alfonso

Illustration by Cynthia Alfonso

Ultimately, it is often when designers confront aging in their own lives that they begin to ponder how to make life better for those with diminishing abilities. When Sha Yao, a San Francisco-based product designer, learned of her grandmother’s Alzheimer’s diagnosis, she began to think about tools that would be useful as her grandmother lost the ability to care for herself. After a four-year design process that involved interviewing caregivers, volunteering in care facilities and hundreds of mock-ups, she created Eatwell, a nine-piece tableware set for people with cognitive and motor impairment. The set’s high-contrast primary colors help users distinguish food from tableware and stimulate appetite, while specially curved spoons and the slanted bottoms of deep dishes make it easier to scoop up food without it spilling over the edge. The set also comes with a cup and a mug, both with anti-tip designs. Still in development is a serving tray to increase the contrast between the set and the dining surface and allow users to attach an apron to catch falling food.

3D printed meal from the Performance Project for elderly consumers on a dysphagia diet.

3D printed meal from the Performance Project for elderly consumers on a dysphagia diet.

“Clients and caregivers told us that patients who have not been able to eat by themselves in years have been able to do it using the set,” says Yao. One customer purchased the set for her sight-impaired mother, who normally felt too embarrassed to eat out at restaurants. The woman reported that now her mother, with a newfound confidence that she could eat without spilling food, was happy to dine out again. Yao’s goal is to reduce the stigma associated with many assistive products by creating objects with broad appeal. “We try to make it more like an art piece for your house,” she says. “Some people don’t want to look like they need extra help, and we want to impress on people that [Eatwell] are not just for special use. We want to encourage the whole family to use this together.”

Yao says she is seeing more and more designers enter the market of assistive products. “Each of them has a story that drives them to work hard on this and try to understand the community much more than other people,” she says. “I truly believe there is a tremendous need in this field and I encourage young people to think through their experience and make a connection.” Designers looking to make their mark on the world may not need to look further than their own families and neighbors for inspiration.