Pre-order your copy of SEEDS, MOLD Magazine Issue 05 here for a pre-order price of $18USD. Expected ship date is March 22.

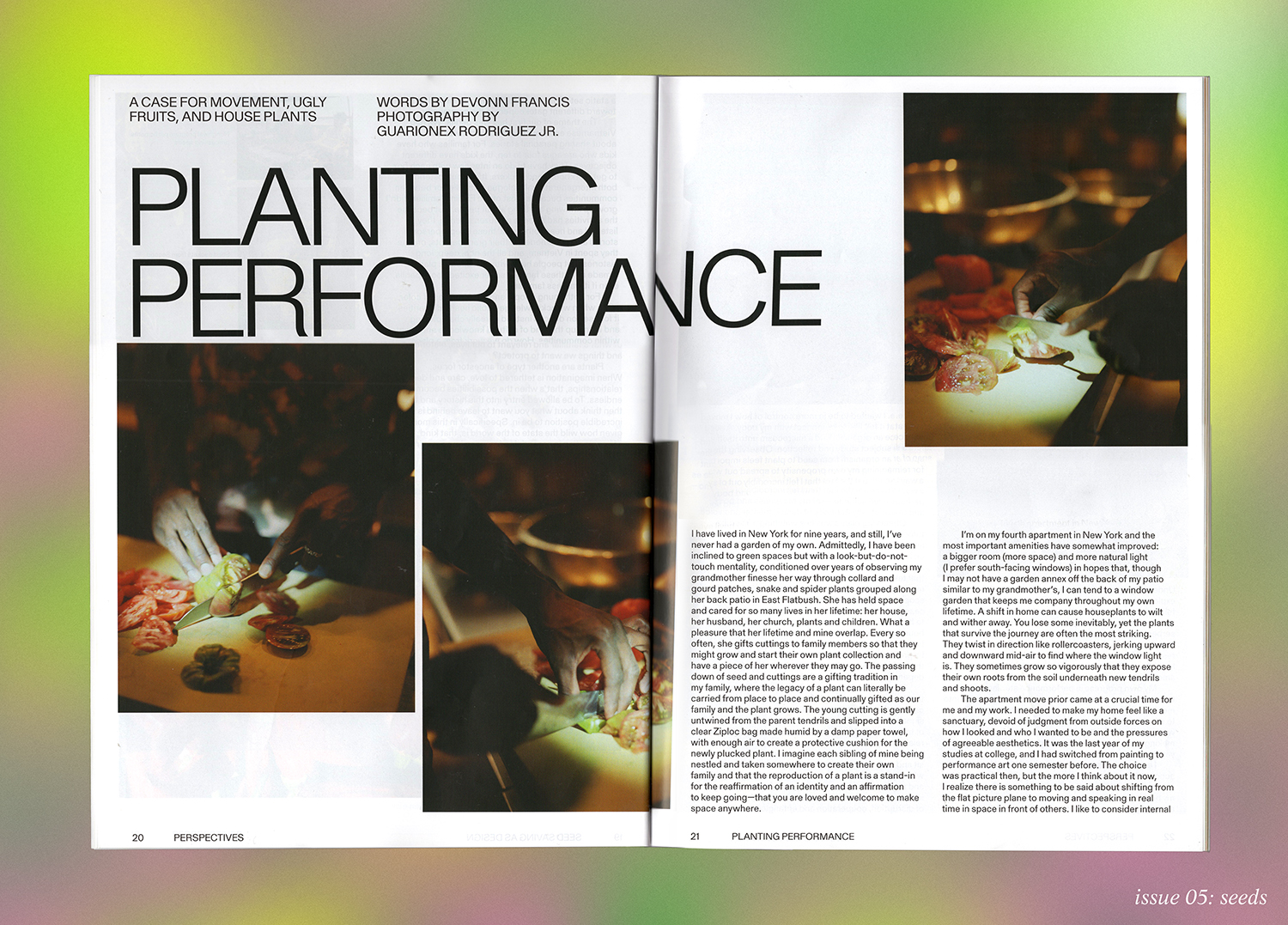

I have lived in New York for nine years, and still, I’ve never had a garden of my own. Admittedly, I have been inclined to green spaces but with a look-but-do-not-touch mentality, conditioned over years of observing my grandmother finesse her way through collard and gourd patches, snake and spider plants grouped along her back patio in East Flatbush. She has held space and cared for so many lives in her lifetime: her house, her husband, her church, plants and children. What a pleasure that her lifetime and mine overlap. Every so often, she gifts cuttings to family members so that they might grow and start their own plant collection and have a piece of her wherever they may go. The passing down of seed and cuttings are a gifting tradition in my family, where the legacy of a plant can literally be carried from place to place and continually gifted as our family and the plant grows. The young cutting is gently untwined from the parent tendrils and slipped into a clear Ziploc bag made humid by a damp paper towel, with enough air to create a protective cushion for the newly plucked plant. I imagine each sibling of mine being nestled and taken somewhere to create their own family and that the reproduction of a plant is a stand-in for the reaffirmation of an identity and an affirmation to keep going—that you are loved and welcome to make space anywhere.

I’m on my fourth apartment in New York and the most important amenities have somewhat improved: a bigger room (more space) and more natural light (I prefer south-facing windows) in hopes that, though I may not have a garden annex off the back of my patio similar to my grandmother’s, I can tend to a window garden that keeps me company throughout my own lifetime. A shift in home can cause houseplants to wilt and wither away. You lose some inevitably, yet the plants that survive the journey are often the most striking. They twist in direction like rollercoasters, jerking upward and downward mid-air to find where the window light is. They sometimes grow so vigorously that they expose their own roots from the soil underneath new tendrils and shoots.

The apartment move prior came at a crucial time for me and my work. I needed to make my home feel like a sanctuary, devoid of judgment from outside forces on how I looked and who I wanted to be and the pressures of agreeable aesthetics. It was the last year of my studies at college, and I had switched from painting to performance art one semester before. The choice was practical then, but the more I think about it now, I realize there is something to be said about shifting from the flat picture plane to moving and speaking in real time in space in front of others. I like to consider internal commitments made in private to move in front of my plants as the impetus for a better connection between how I think about movement, plants, and the knowledge one carries in their body. Plants offer passive encouragement to proliferate at a moment in time where queer black growth is often stunted and robbed of its chance at a full life.

I like to think of plants as mentors and mirrors. The way that I move and therefore think about freedom of movement is an ode to them. When I wake up in the morning my ritual is a deep stretch towards the light, just as they do. I clasp my hands over the back of my neck, standing upright on parquet flooring, and let the weight of my hands and every breath ease the bottom of my chin into the recess between my clavicles. Under varying conditions, the small seed nodule explodes beyond its own bounds to transform into a fully grown plant that kinks and unkinks itself toward the window light. A lanky stem produces an army of serpentine anchors through the soil. A pioneering circuit of veins tunnels through wet darkness. Green leaves resist the force of gravity as if to ready themselves for a handstand. The details are slow and take a considerable amount of patience.

My own progress in performance studies and the trajectory of a seed’s growth inspires me to get back into moving to celebrate being in my body once again. That is to say that personal space is about having time to deal with your body, uninterrupted, with plants as my referent making very complex biological projects seem elegant yet simple.

I envied plants for their freedom. What I hadn’t accounted for was a lesson in plant politics that would set me on a path toward a deeper relationship to food, my body and performance as a way to practice autonomy and really mean it, to heal from self-harm and public violence. I wanted to be in more control of how I moved and what it felt like to reconnect with my body. A seed is at once an organism and a microcosm unto itself and offers a subject study and reflection. Observing the lifespan of an organism from seed to plant feels important for reimagining my own propensity to spread out wide as a way to confront the fact that I felt incredibly out of sync—perhaps even ashamed—of my blackness and body and to explore my curiosity of dance, theater and voice.

Observing plants was like watching a Youtube tutorial on how to unloosen from my own cage of ribs and skin. Seeds offered, in this way, a dance lesson on how living organisms perform in a given environment. A seed contains a genetic code within their seed body that takes us backward and forward in time. A seed’s memory holds fundamental knowledge within a microscopic library with unfinished essays on weather and seasons best fit for proliferation, its determination to find the sun and how it may have traversed geographic boundaries—each document housed in its infinite hallways. The seed knows what is happening to the land by proliferating where fertile and shrinking where futile, the knowledge marking the miraculous seedbody’s dependence on where it settles.

Plants model the kind of behavior that I hope that humanity can scale. Within any biological system, cooperation dictates how well everyone does—signaling how well we know each other and the types of friendship and kinship we sustain—with generative relationships as our metric for success. What was once a mutable and normal thing became a reason to sit and wait—to come back to the very same spot where you left it to see how it bends and browns, wilts and regenerates. The performance of seeds as they interface with the environment is a powerful example of disruption, cooperation and entanglement. Just as the human body holds our organs and our muscles remember exhaustion or stress, the body of a seed holds biological mechanisms that repeat generationally, inheriting knowledge that helps them find beneficial landscapes to inhabit and thrive in. Seed bodies reflect what it means to be connected—to be part of a more cooperative system. In this way, we write our generational blueprints through performance and witnessing.

Recently my performances have been an attempt to learn new systems of care that hold space for ancestral knowledge and build capacity to demonstrate this knowledge to others. Muscle memory is not only how you feel, but what you know about how you feel. As I bear witness to the plant’s performance, I understand that historic and ancestral knowledge is inherited and passed along, giving our human experience the tools to measure growth in meaningful ways. We allow ourselves a type of awareness based on how we identify, how we signal to one another, and what might be beneficial or harmful to ourselves and others. This observational awareness is a benchmark for accessing past situations and defining futures where we feel safe and secure. I am responsible for what I have witnessed. To be an observer is not to see something and walk away. It is to be a willing participant in the performance.

I have always believed everyone in their own right is a performance artist. In reality, we are nodes within a larger organism that can be an agent of some sort of radical change. As we build capacity for safe, secure and cooperative futures, our present observations and the knowledge that we hold in our bodies should be accounted for in ways that serve to uplift and encourage diversity, friction, and difference as positive forces that help us to participate in an ever-expanding nodal world.