From MOLD Magazine: Issue 04, Designing for the Senses. Order your limited edition issue here.

Natural farming is a call and response practice; it requires physical and emotional adjustments and a good imagination. The land guides us to care for it in a way that is generative and self-renewing. I have chosen to follow and respect the principles that the land presents. I have been inspired by the dynamic and uncompromising capacity of nature. I am tasked to be both the caretaker and the witness. I have learned to watch the soil for good ideas.

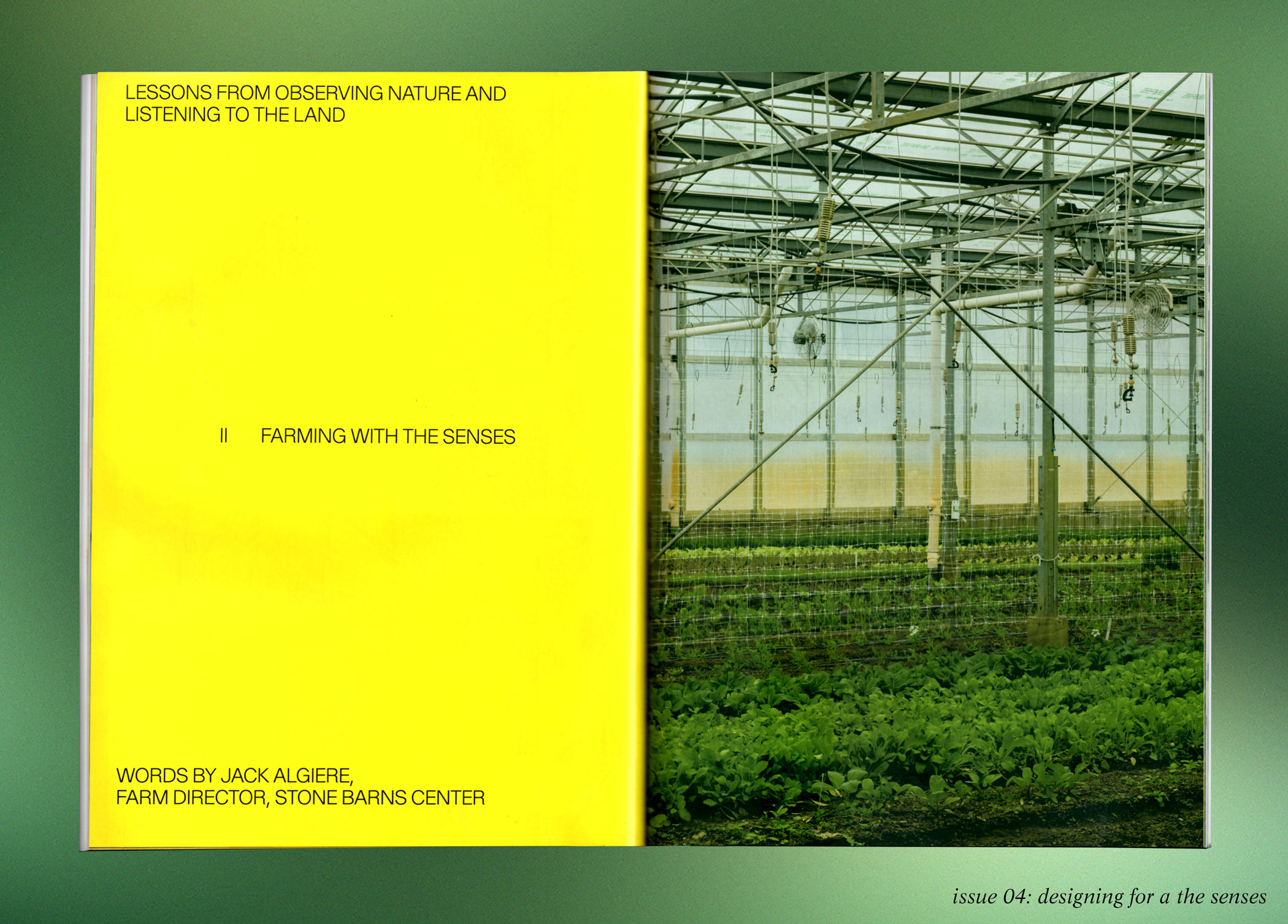

Photography by Thomas McCarty.

The idea of farming with the senses is intuitive—it’s about emotional relationships and how we embrace an embodied experience that informs our decisions. It starts with expanding our perception of what’s going on by being available to all the information around us: when farmers talk about seeing beauty or taking in smells, we’re really talking about interpreting what we perceive to inform our management practices day by day. This holistic approach shapes a philosophy for caring for the land and maximizing the health of the plants and animals we grow, and the people doing the work.

Most of the best choices for a system like this are gleaned from natural mimicry and observing nature: the innumerable ways nature overcomes challenges on her own, the way the wind blows and affects the health of a plant, the particular pasture on a hillside turned slightly toward the sun, the potential in a forest edge that harbors certain insects.

The more I do this, the more those practices develop into methodology. With experience, I am better able to assimilate the apparent anomalies into my understanding of the landscape; the complexity wrapped up in this system is boundless. I constantly chase that complexity with my increased understanding of the place.

Subtle changes become more evident with every additional season of experience. We can’t always see the changes with our eyes, but we perceive the cyclical shifts by using all of our available senses—a skill that is refined and sharpened over time. You can’t see the color change in the buds in a tree, but they’re starting to flicker with life. The sap is flowing on the inside. The sun gets a little brighter and a little higher in the sky. By the second week in February, the tender carrot tops in the greenhouses begin to stretch toward the warming sun, echoing the patterns of activity underground in our fields. Growth is happening outside of the visible realm, but it’s there. We watch for the shifts in the cycles throughout the seasons. We take cues by staying in an endless dialog with these natural cycles.

This is a different approach from most modern agriculture, which is prescriptive and reductive. Twentieth-century industrial food and agriculture models left us in the dust of an unfulfilled promise of bigger, better, faster. But the homogenization that accompanies that promise stymies curiosity, intuition and self-confidence, stripping the artistry and stewardship from the work. It’s led us astray from one of the most beautiful, rewarding aspects of farming: relating to the broader community by connecting over food and land. It’s also led to a society-wide disconnect from and devaluation of flavor, the embodiment of the fruits of agricultural labor as it becomes part of our own bodies. This is one of the modern system’s greatest tragedies, among many others.

At Stone Barns, we are working in an integrated system that weaves together vegetable crops, small grains, about 350 acres of grassland with a multi-species livestock operation, and wild spaces. We farm in harmony with the natural system and generate connections with our local community using farming and food to strengthen ties and a sense of shared responsibility for the land. We strive for a diet and a way of eating that is firmly situated in this particular place so that we learn to relate directly to the way we care for our land.

This community- and ecology-based approach to farming, driven by an ever more refined sensibility and sensitivity to what the land is telling us it needs, lets us plug into the ecosystem with depth and authenticity. We then have the opportunity to interpret the land in the form of delicious, nutritious foods that spark a dance between farmer, chef and community, building recipes and curiosity. From that dance comes diet, cuisine and culture that is really an artistic expression of place. We have the capacity to do this in every community.

We don’t have to go back in time to a glorified pastoral past to tap into the particulars of a place and community to guide our farming practices. The most exciting work in this space is happening right now, and the more we embrace the delights of this generative moment, the more interconnectedness we achieve as a community.