Oysters in New York weren’t always a delicacy: in the early 19th century, oysters cost less than a penny, and were served as snacks from street vendors. In today’s currency, this would be around 70 cents, a quarter of market price. Oysters used to be so abundant, their reefs covered 350 square miles of the Hudson River Estuary, at least 3 trillion individuals in the New York metropolitan area alone. Thanks to industrial pollution and unsustainable harvesting practices, oysters are now practically extinct in the area, and of course those that remain are entirely inedible. There has been, however, a considerable amount of attention in recent years around the reintroduction of these brackish creatures into the New York Harbor.

WATER QUALITY

Aside from increasing local biodiversity and overall ecological resilience, the reintroduction of oysters has a number of added benefits that could save billions of dollars in direct costs, and billions more in avoided storm surge damage and pollution management. Oysters, as a keystone species, are involved in the maintenance and improvement of water quality, with the capability of filtering 50 gallons of water per day. In the New York Harbor, this means huge savings for the cleanup of the industrial-scale pollution still present in the area, but don’t expect to see those oysters used for cleanup on a menu anytime soon. “Oysters incorporate toxins into their bodies—if they are eaten, the toxins move up the food chain,” explains Pete Malinowski from Billion Oyster Project. The Billion Oyster Project is one of the main proponents of using these friendly bivalves to help restore the ecosystem of the harbor through oyster production, reef construction and monitoring, shell collection and education.

The Billion Oyster Project (BOP) aims to fulfill the promise of its name by reintroducing 1 billion oysters into the Harbor through a number of partnership actions from non-profit initiatives to massive eco-infrastructural designs. The initiative has already resulted in 11.5 million reintroduced individuals across more than an acre of restored reef, the effect of which has filtered 10.9 trillion gallons and removed 6.75 million pounds of nitrogen from the water.

OYSTER-TECTURE

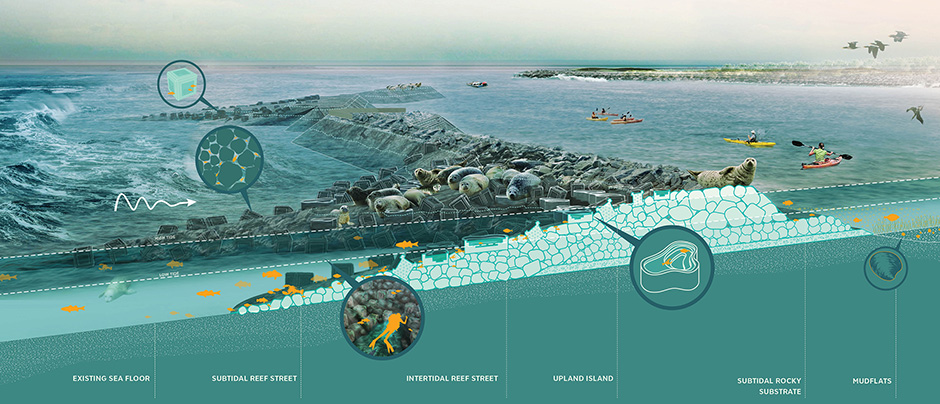

In 2010, MoMA’s Rising Current exhibition showcased the design potential for revitalizing the historic oyster population. SCAPE Landscape Architecture was not only involved in this education and visioning project, but also is in the schematic design process for a funded project “Living Breakwaters,” employing founder Kate Orff’s “Oyster-tecture” concept to create the first iteration of a replicable project aimed to mitigate storm surges (like Superstorm Sandy in 2012) that can erode and damage coastal communities.

The project consists of massive oyster reefs off Staten Island—at the mouth of the Harbor—that would mitigate damages from future storms while filtering huge amounts of water, and fostering the revitalization of the ecological communities that once inhabited the area. While “oyster shell is one of the best substrates for oyster spat to attach to and grow on,” explains Lauren Elachi, SCAPE Project Designer, “Living Breakwaters is in a high wave-action zone, [so] our ‘engineered’ approach is to integrate the shell into Econcrete units—building cages for the shell so that we can structurally integrate the restoration into the breakwater”.

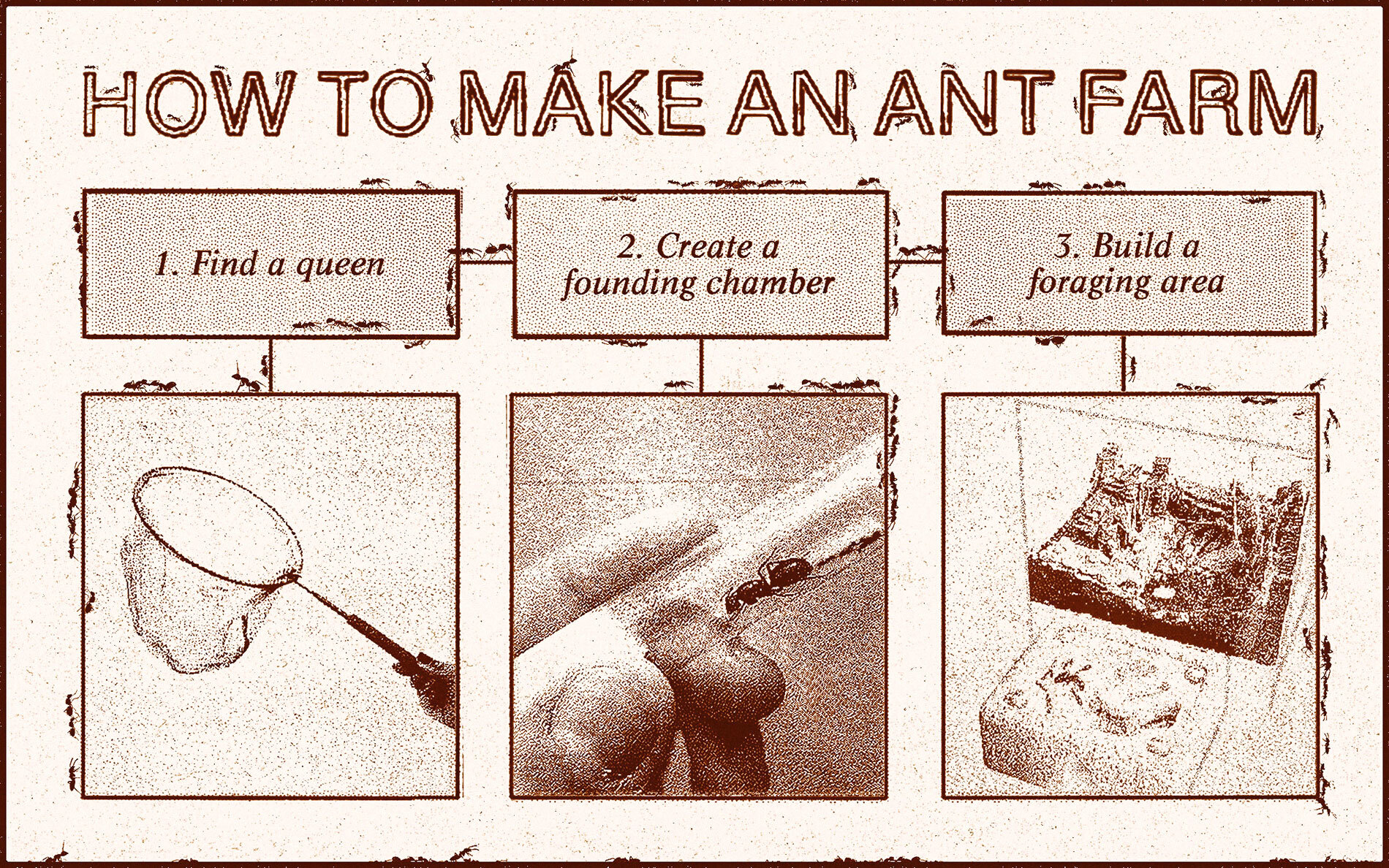

Although we won’t be eating oysters from New York Harbor in the near future, the oysters we are eating in New York City are contributing to the oyster-tecture of the future. Because oysters build reefs on the backs of their predecessors in a process called Spat-on-Shell (SOS), almost 200,000 pounds of oyster shell have been collected from restaurants, thanks to BOP’s partners like K&B Seafood, who facilitate the redistribution from a long list of participating restaurants. Many of these shells will go into a Jamaica Bay project this spring, creating a substrate upon which introduced oysters can attach larvae.

EDUCATION

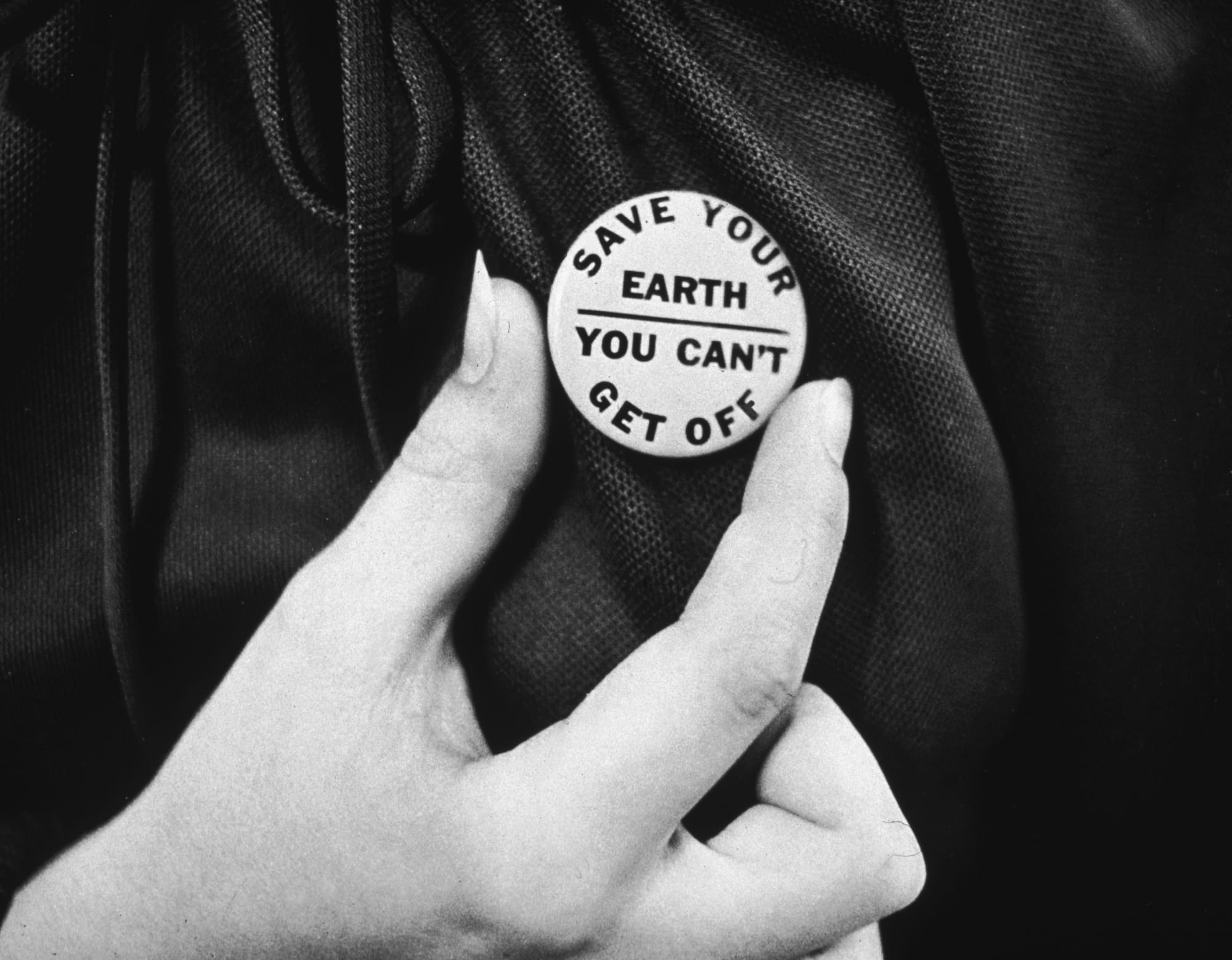

The reintroduced oysters wouldn’t be edible for decades, if ever, but one major concern is that local fishing communities would disregard this warning, and illegally harvest and eat the bivalves. The NY Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) has been resistant to some of these projects, because they see the oysters as an “attractive nuisance,” as Malinowski described. “The idea is that New Yorkers will not be able to help themselves from harvesting our poisonous oysters and feeding them to their families.”

Volunteers with the Billion Oyster Project

Volunteers with the Billion Oyster Project

This hasn’t stopped numerous research and design proposals, many of which are in effect today. In addition to the BOP, the Oyster Restoration Research Partnership has been monitoring six 15’ by 30’ research reefs, including locations in the Bronx and Governors Island. Involved with both partnerships, the Urban Assembly New York Harbor School employs more than 430 students in crucial roles revolving around the maintenance and research of the many oyster projects in the city.

THE FUTURE

“If we ever stop pouring raw sewage directly into the Harbor as we do now when it rains, it is conceivable that the oysters would be just barely not too poisonous to eat. That’s not too appetizing from my perspective,” explains Malinowski to the concept of one day farming oysters from the New York Harbor again. In addition to “improvement in the water quality of the Harbor, and a regulatory paradigm shift from the DEC,” Elachi also notes that “a sustainable population size of oysters would probably the biggest hurdle” to the potential for NYC oysters to ever have a chance at finding themselves on our plates in the future.

While the New York restaurant The Mermaid Inn’s Oysterpedia app seems to be a comprehensive tool for oyster connoisseurs, the oysters involved in these research projects would ultimately be toxic and inedible. Unless a new food project that resembled Smog Tasting by the Center for Genomic Gastronomy, it’s doubtful that the leftover toxins or the murky polluted waters would enhance the nuanced flavors of the “Metropolitan Harbor Oyster,” or Crassostrea Pollutica, shall we call it. Malinowski finished with this personal advice: “there are hundreds of oyster farms within a few hundred miles of New York City, they all grow oysters in beautiful pristine waters. That’s where I like to get my oysters.” So, for the foreseeable future, we’ll continue tasting the brine-y flavors of bivalves from far-off locales like the the Barcat from the Chesapeake Bay, a Totten Inlet from the Puget Sound, or a Beausoleil from New Brunswick.

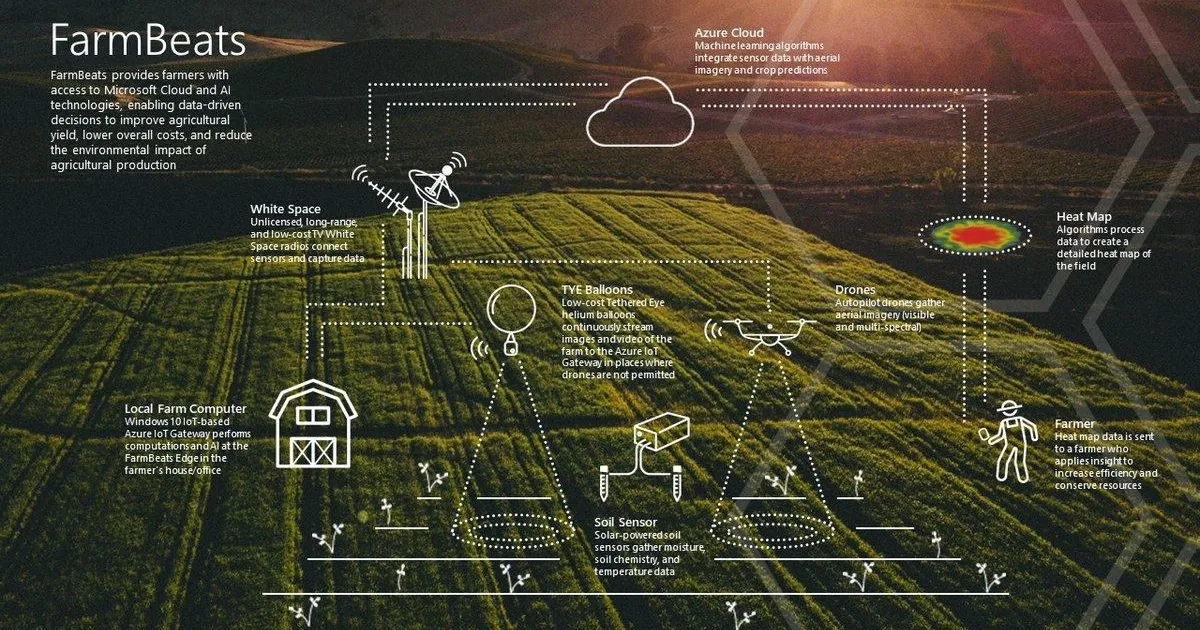

This article is part of MOLD’s spring editorial series GROW highlighting new systems and technologies in agriculture innovation.