“Might I recommend the honey and miso fried locusts or the caramel coated locusts as a starter?”

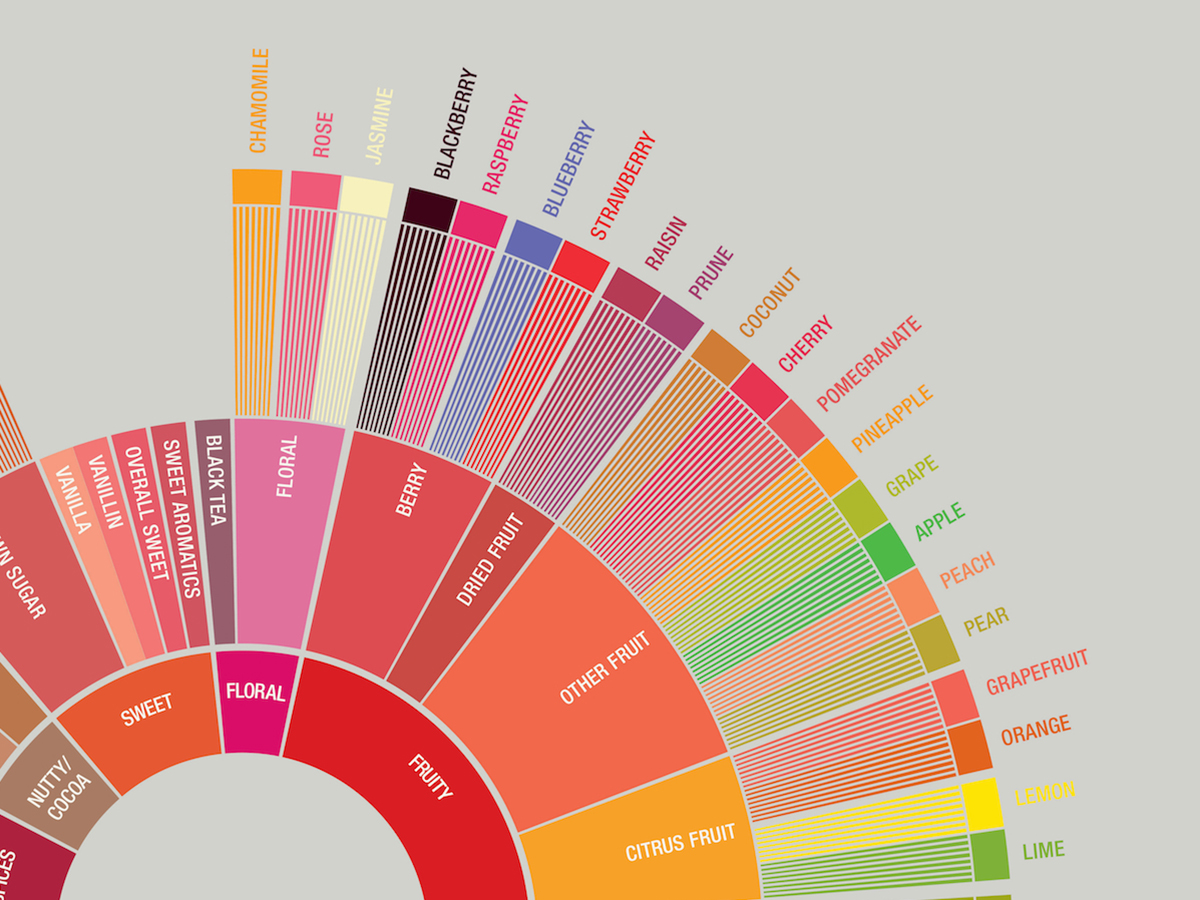

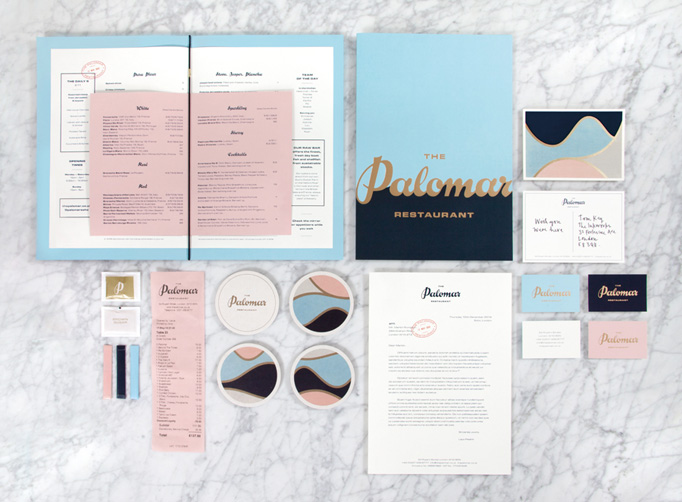

Welcome to Hoppers: The Locust Bistro, a concept art-dining project ideated by Dubai-based designer, Sahil Assadi. The menu is a homage to a most revered ingredient relished across communities, celebrating the locust in a necessarily urgent manner. Assadi chooses to combine the locusts with flavor profiles that he enjoys cooking with, while also making the ingredient accessible to a large number of people hesitant to try the “sky shrimp” as it is sometimes dubbed. “A flying protein has taken over the Earth. While most people view this as a threat, we view it as an opportunity to add finesse to an ancient ingredient,” he says. The menu offers us a perspective on the myriad ways in which the ingredient lends itself to modern global cuisine. From Coca-cola marinated wings, to tacos, to Sri Lankan rice hoppers and coconut curry, The Locust Bistro serves diners comfort food elevated simply by its ingredients.

Suffice to say, locusts have been around a long time. Having lived alongside them and the biblical proportions of havoc they wreak, for thousands of years, it comes as no surprise that humans have long since eaten the critters. Locusts are considered to be a highly nutritious source of food, for both humans and other animals, with 50% crude protein per 100g of dry locust. In the book The Diet of John the Baptist by James Kelhoffer, it’s said that locusts dipped in wild honey were part of the prophet’s regular diet. In much of the Middle East, Baluchistan and Sind in Pakistan, locusts were preserved for long periods of time by smoking and salting them. In 1964, after a particularly bad infestation in Old Delhi, locusts were caught, stripped of their wings and legs, and fried in clarified butter. In Morocco, people would boil and fry the lower halves of the locusts as the eggs were stored there and are believed to be very nutritious. Greeks would even grind them to make a fine protein rich flour.

Desert Locusts are a type of grasshopper, belonging to the Acrididae family. Evolutionary adaptations have granted these locusts the ability to survive, thrive even, in the most unforgiving of terrains. Most of the time locusts live in solitude, blindspots in the vast desert for years, but when climatic conditions change and moisture increases in the area they transform. Locusts enter into a phase that entomologists refer to as “gregarious”—this is when they increase in numbers, size and color. As they do so, “they sense one another around them” says Rick Overson of Arizona State University’s Global Locust Initiative in an interview with NPR. “Instead of repelling one another, they become attracted to one another—and if those conditions persist in the environment, they start to march together in coordinated formations across the landscape.”. Once they enter this stage they can multiply twentyfold in three months and gregarious locusts are born for the next few generations. These swarms then proceed to cross 130 km over land and sea per day, eating everything in their path. A single square kilometer swarm can eat as much food in a day as 35,000 people.

Currently, over 23 countries across the Horn of Africa, Middle East and South-East Asia are affected grievously by swarms of locusts. For some of these countries, there has never been a worse attack in known history. If attacks continue on as large a scale, the United Nations FAO says they will destroy the livelihoods of 10% of the world’s population. Considering the drastic alterations to life as we knew it courtesy COVID-19, countries are now urging their citizens to “go vocal for local” in a way to safeguard local economies, and supply chains. There has been a strong movement for local, seasonal eating the world over and it begs to question whether locusts should be on more plates globally.

So why aren’t we eating them, or at the very least, using them as animal feed? Threatened by food shortages and drastic loss of livelihoods, governments have chosen to use toxic pesticides and insecticides to kill swarms of locusts. Some of them are known neurotoxins, and chemical residues even after cooking the locust can cause severe health issues to anyone consuming it. It would be difficult to identify the toxicity of the insects at a household level, and so it may be best to err on the side of caution. However, given how strained food systems are today, it is imperative that we look at this situation holistically. It is not without reason to urge governments to use bio pesticides such as linseed emulsion with caraway, wintergreen and orange peel oils, or encourage bird populations as natural pest control systems. With climate irregularities increasing, we are bound to see more attacks, each one stronger and longer than the last. Here’s looking to tomorrow, where we will find a solution that doesn’t trigger a new cycle of problems while allowing us access to a traditional ingredient that could very well change the future of food. Until then, we will dine at Hoppers: The Locust Bistro at 9 pm on Thursday, inside the confines of our imagination.