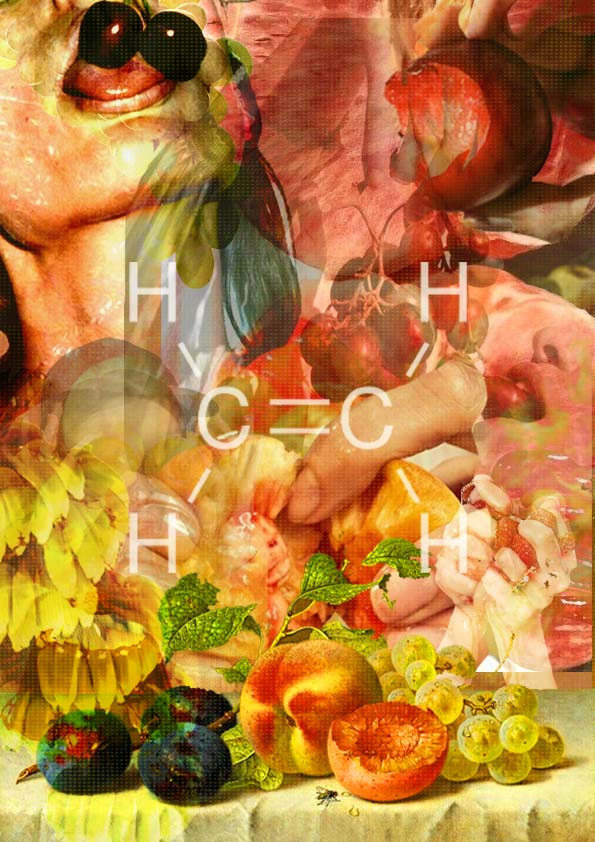

As I catch up with designer Adelaide Lala Tam, we talk about the aftermath of her project 0.9 grams of brass, and sit down to discuss her newest work, Consuming Romie 18, in which she follows one cow throughout its lifespan, up until its arrival at the slaughterhouse, and the butchering process that follows. Tam developed a plan to consume and utilize all elements that the cow can provide over the course of its life and afterlife. The project aims to investigate the complex system of cow husbandry.

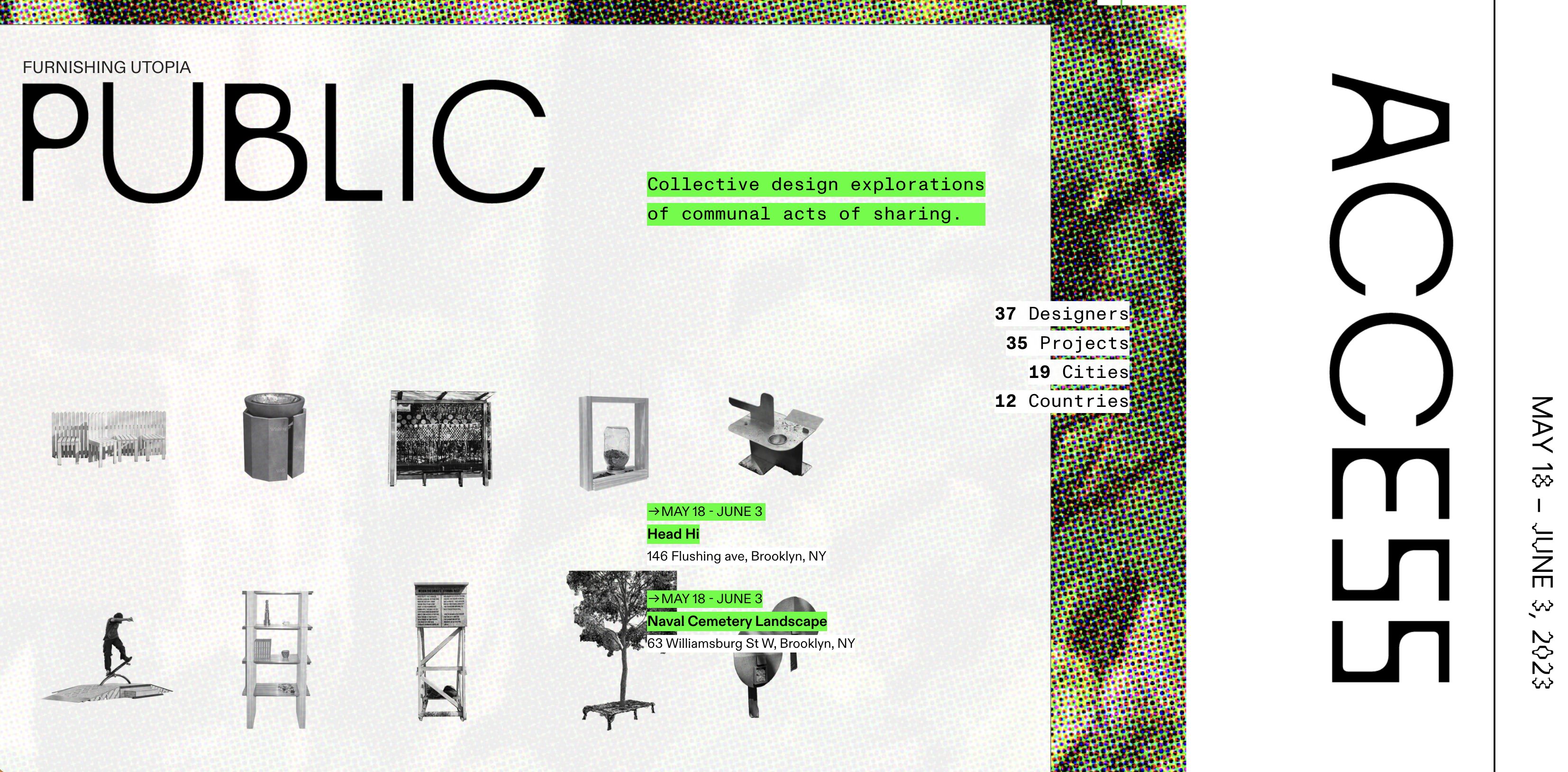

Adelaide’s exhibition, ‘Farming The Future’ has just closed, after showcasing her previous projects focused on the farming industry, and her progress into her work with Romie 18. Among the half packed objects that were featured in the exhibition we begin our conversation.

A lot of your projects now revolve around cows, you even get the title of ‘cowgirl’ ascribed to you sometimes, how did that come to life?

“This series of cow related projects started off with a visit to a slaughterhouse, after seeing the industrial slaughtering process, I wanted to find out more, I was kind of shocked by the brutality, it really put me off to eating meat. After that I took a break from school and visited an indiginous village in Indonesia, where I saw the process and ritual of slaughtering a cow in a sort of ‘primitive’ way. There I saw the respect and understanding of the whole cycle of life. That showed me that there are many ways to consume a cow.”

“After doing projects about the meat cow and the milk cow (0.9 Grams of Brass and the Ultimate Milk Cow), I wanted to know more about the man made system behind every single cow, so that is why I chose one cow to walk me through this system. Her name is Romie 18. I chose her because I took a liking to her during my volunteering at the Genneperhoeve.”

Adelaide tells me the project actually had its start two years ago; after the slaughterhouse visit, she decided to help out at the biodynamic farm De Genneperhoeve.

“It became so confronting I needed to do something with it. So the move to volunteer at the farm here was based on my intrigue of finding out how the system behind farming works. So I started helping in the middle of winter, the sun would rise at around nine, and I would be there at six—six thirty, in the freezing cold, cycling alone through the forest.”

What have you discovered thus far?

“The Dutch cow is really ingrained in the culture, it is the country of milk and cheese. Almost everybody knows a farm or lives close to it, it is such a prevalent part of the landscape here. It surprised me how accessible all this data on these animals is. I also think it is a privilege to have access to all this information. Coming from the city of Hong Kong, there is a lot less opportunity to see where your food is grown, here it is always closeby.”

Adelaide plans on eventually serving up Romie 18 to a table of dinner guests at the beginning of next year, telling me that, “The project will run one and a half years and in the end I want to show this story of this cow in a dining event. We’re now halfway in the project, I started following Romie in November last year, and just two weeks ago I got the first cheese from her. To me it really has character when I taste it, it is different than the other cheeses here. I will save a big wheel to create an old cheese that will be eaten at the dinner.”

The dinner itself will show all parts of the life of Romie 18; Adelaide notes that, “I want to give people the feeling that they would like to eat this cow, but also appreciate it thoroughly. I don’t want people to feel disgust. It is about understanding the idea of a life that is part of an economic system.”

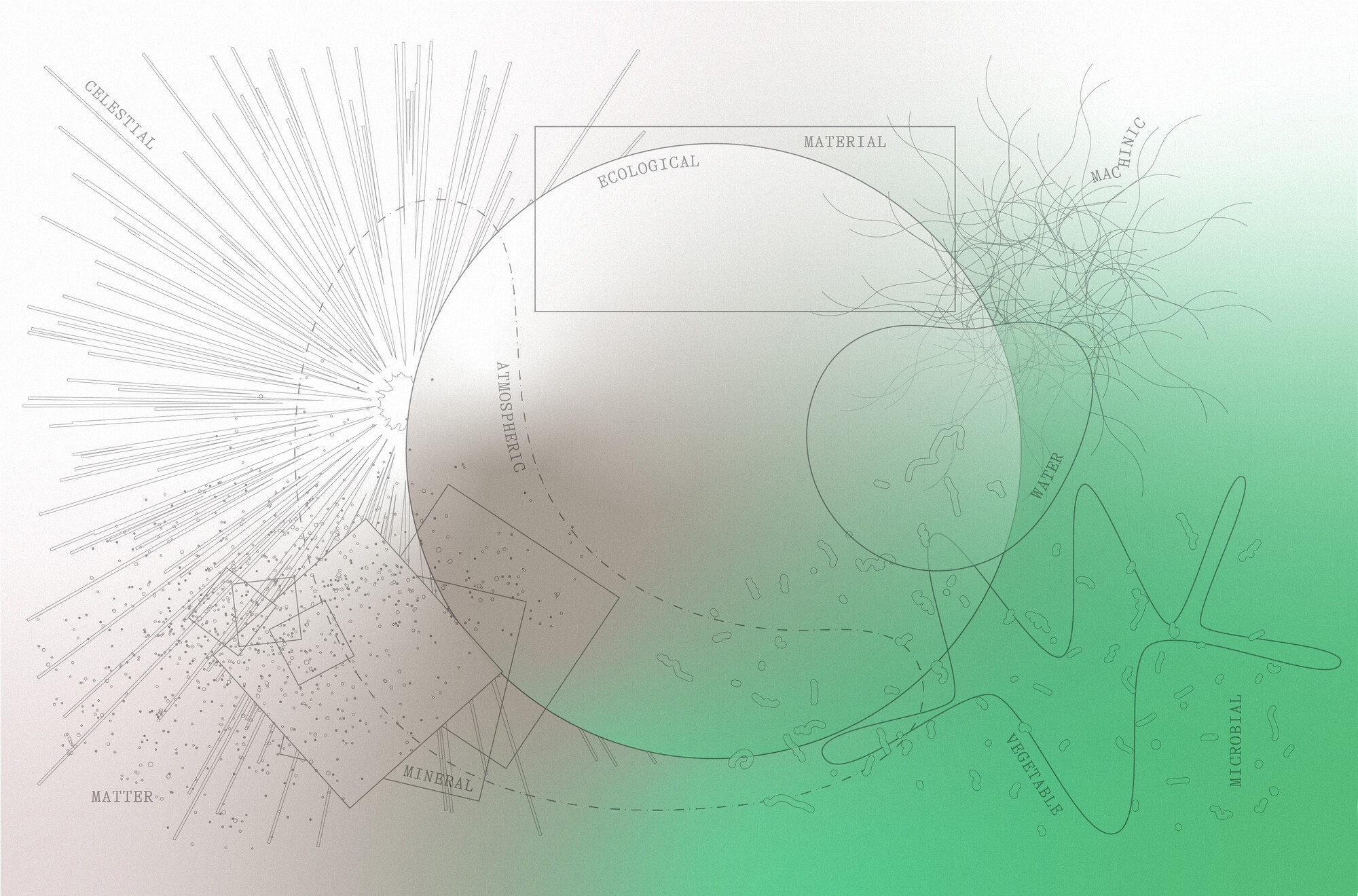

Adelaide talks a bit more about the exhibition that just finished, and shows me the archive she already built up on Romie 18, “One of the parts of the ongoing project about Romie 18 was looking at the heritage of the cow, some of her sisters are in the same stable, I would have never known this if I didn’t see this system behind it. Because we don’t see or know, and quite frankly don’t have access to these lineage systems, we tend to look at a cow just as a singular cow, but it is kinda like being introduced to friends and family at a party, knowing the connections adds more layers to this life.”

The first cheese must have been a big milestone in the project, what are the other major parts to come?

“She is going to give birth in summertime, and the slaughtering will be a really big moment, but before the dinner I have a lot to research and document, usually when you bring a cow to the slaughterhouse, you don’t get the hide, because they bundle them up and sell them to leather companies. If the official price is 100 euros for example, because of them taking the organs and hide, you maybe only pay 80 for the slaughtering. I have to break that bureaucracy to get all the parts of Romie 18.”

What happens after the slaughter?

“I want to look at where all the materials of the cow go afterwards. I will see if I can make bone china and tan leather.Then I have to bring this one skin to a tannery. Even firing the bones, do I bring it to a crematory for humans or another oven? I have to find that out. Maybe I am making a coffin for the cow then if necessary.” Adelaide laughs while she goes through her options. “But what I want to state is that I just want to recreate the experience of processing a cow so that people can view it, I don’t want people to think or feel this cow is the most special cow, although I like it, I want to show a normal cow, that could be standing anywhere in the world.”

“I’m not only documenting the edible products, there are so many objects that feature in the life of such a cow, from ear tags to the medicine vials and insemination tubes, what I experienced now is that raising a cow does not only use a lot of resources, it also takes a lot of care, when they milk the cow they examine the cow, there is a lot of medication that is utilized if the cow is sick, it is not a standardized process, but it responds to the life of the cow. Much more human like. They also need medicine and hygiene products.”

You are making the plates for the dinner from Romie 18 as well right?

“As for the bone china, I want to see if I can show the story in the design of this as well. All the info of her life, I want to integrate into this commodity. Same for the leather. A super simple product. I am thinking of making something small of which I can make a lot.”

Why this tiny countless object?

“I love mass production, I really like the ‘accents’ it gives, The repetitive widespread aesthetic of a mass produced object, it is sort of identyless and universal in that way. But subverting it by giving it value. The value of the life of the cow gives the value to these tiny objects, not their actual monetary value.”

Did your feelings towards Romie 18 change?

“Yesterday I ate a bit of beef for the first time in a long time, biltong from South Africa was given to me by a good friend, that I did have to try. But because I have seen the whole slaughtering process with my own eyes, I don’t eat beef anymore. When I look at the beef on a plate, I will imagine how this cow must have looked. I developed a strange connection with the face of cows. My cravings for beef sort of went away. Because of not eating beef, I changed my diet to include more eggs, chicken and the likes, but that is getting me interested in the life of chickens too. Chicken farming is actually bigger than cow farming here in holland. Chicken farming is also a big industry, the quantity of chicken slaughtered is much more than cows. Before seeing it firsthand I knew killing a cow is cruel, but it was tasty for me, and I enjoyed eating it. At the moment I don’t know anything about the process with chickens, so my drive is to bite into these topics and find out how these processes go. What I eat is based on my understanding of the process behind it, that is why I see the chicken industry as a new avenue for a project.

After my first project, people asked me a lot if I am a vegetarian, and many people did not believe me when I told them I am not. For myself, the answer is that I don’t know yet about this life of a chicken, I want to see this with my own eyes and believe that, then I will make my judgement, I see it as an opportunity to investigate for myself. The cruel videos on the internet aren’t the complete truth, as are the utopian picture of some farmers. I really want to use my own eyes to research and see the life of these animals.”

Is the life of Romie 18 the ‘best’ life for a cow?

“I don’t know if you kill a cow and eat it, it is the best life. But in the general system, this feels like a better way. At the end, when this project is finished, if I can get the dinner guest to really think about the value of this life, it may have been worth it.”

Would you consider doing this project again on a large scale industry farm?

“Yes, I would love to,” Adelaide sparks up. “That is my dream. What I am doing now, I know the Genneperhoeve is a very ‘sweet’ farm. But as a designer I want to do something more impactful, a bit more “mass quantity” a bit more close to reality. Genneperhoeve is my foot in the door, food production is a very sensitive industry, especially meat production, because they are scared of animal activists, scandals and hygiene problems, so with the small scale I wish I can convince the big farmers.”

You focus a lot on showing information, but does the project have a message attached?

“I do have a message, but it has to be well curated, in a way which leaves more space for the consumer to reflect. My intention is to become a mediator between the people and the food, of course I want to say something about the animals, but I want to leave the interpretation to the consumer. I want to provide this medium in a transparent way, for people to make their own decisions.

For the vending machine project I get quite some reactions still, most people catch the message immediately, they see that my intention is not to scare people into not eating meat, but to use the paperclip as a reminder of the loss of this one life.

Some people recommended me to connect to animal activist organisations, to help promote the project, but that has some conflict with my own intentions. The message they express is maybe close to my message, but my intention comes from a different place. It is not my intention to stop people eating meat, but to let them think about the meat that they eat.”

Where do you see the future of cows going? Do you see a path we might take or should take?

“There is so much cow involved everywhere, from the pasty to the coffee and butter. It is so entrenched in the culture of The Netherlands it is going to be hard to change, but maybe it will someday, artificial milk and in vitro meat are coming along. In my youth in China, being able to drink milk was a bit of a luxury, real fresh milk is quite a luxurious family habit. Butter and cheese are not used in the cooking at large. So I can see a larger culture where dairy is less prevalent, but maybe in The Netherlands it is going to be harder.”

You are not assuming a lot when you start your projects.

“I try not to, as much as I can, because if I assume too many things, it also blocks a lot of possibilities and opportunities to dive into the situation. It is a designer role I have to get into. This curious open mindset is how I approach the projects, in normal life I worry and plan a lot, but for the curiosity in a project there is no boundary or planning, I just explore.”