Pre-order your copy of SEEDS, MOLD Magazine Issue 05 here for a pre-order price of $18USD. Expected ship date is March 22.

What is a Korean pepper and how does that present a design challenge? When our seed saving group first talked about working with the Seed Savers Exchange, a nonprofit organization that preserves and sells heirloom seeds, this was the question we asked ourselves. Seed saving is an act of creativity. Seed saving is a form of design. By embracing the varying perspectives people have, we get a robust set of interesting genes to perpetuate on a seed level.

When I started Namu Farm in 2011, a partnership between myself and the Namu restaurant group in San Francisco, seed saving became an integral part of my life, partially out of necessity as a lot of the seed we originally planted was shared with me by some Korean community members as well as family members of the owners of Namu. But when I went to Korea in 2014 and met with farmers there, seeing the biodiversity of Korean crops—different varieties that were regionally specific or beautiful landraces that had been developed by peasants—changed my perspective. Whereas I had access to maybe one type of Korean pepper in California, experiencing the diversity of those Asian crops made the existential and philosophical principles of seed sovereignty deeply personal.

Seeds relate to people’s sense of survival and their ability to continue to craft community.

So many communities that live in diaspora know how integral seeds are to their stories—seeds that came with them when they faced uncertain futures. Communities that have been displaced or have migrated know that seeds have always offered a tangible opportunity to put down roots and have a comfort of home, even in terrifying times when they didn’t know if they would ever see that homeland again.

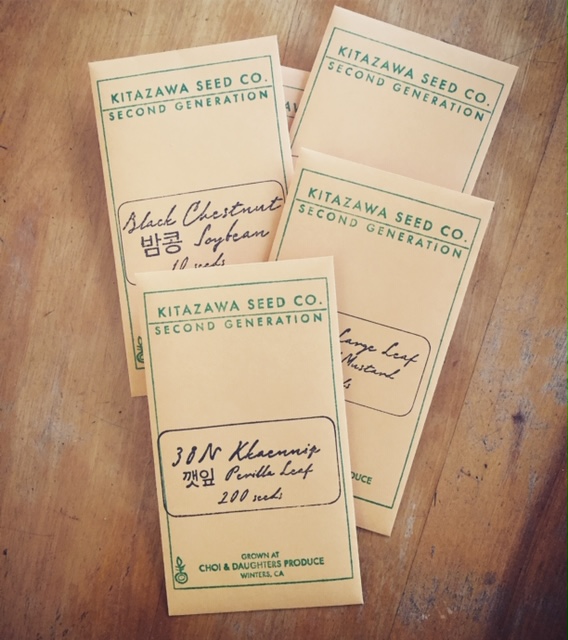

The question then becomes, “Who decides what seeds continue? Who are we improving and breeding crops for?” I started Second Generation with the Kitazawa Seed Company, a 103-year-old Japanese American seed company, not just to preserve the seed as a product but to preserve the seed as part of a more holistic relationship, one where farming is an act of placemaking rather than just the production of food.

In the context of climate chaos and uncertainty, biodiversity is seen as such an important thing, but it is also important because of the diverse sets of cultural perspectives—we need people to like really bitter, slimy, or spicy foods, those less desirable traits from a dominant, Eurocentric narrative—and ways of evolving that are intertwined with those seeds. For me, it’s not a matter of social science, but there are specific needs in terms of plant genetics and biodiversity that must be addressed by being as collectively minded as possible.

In the seed sovereignty movement there’s a focus on rematriating seeds from government seed banks to their historic communities. The ways that many of those seeds have been collected suffer from an editorial perspective that is reductive, where the value of something like a soybean is quantified in terms of crude protein and linoleic acid. Instead, we need to include the inputs of people who may not have degrees in plant science or work at big seed companies but who are familiar with those crops in a different way. We need to start with a crop’s relevance to people, not because we’re trying to keep things the same forever but to know that there are so many unique things that developed in the relationship between plants and people. If we lose sight of the ways people used fibers or built tools, then we’ve lost the direction for what’s possible.

There’s nothing like seed saving to give you a tangible way to plug into a kind of never-ending story.

By moving beyond defining things in terms of their utility, I was able to access the lessons plants have to teach. There’s nothing like seed saving to give you a tangible way to plug into a kind of never ending story. Through seed saving you get to see what was considered beautiful or delicious and all the decisions along the way that impacted the expressions of a plant in relationship to the domestication process. As much as I’m about preservation, I also think in terms of new iterations of crops moving forward. A reverence for history doesn’t mean enshrining things where they stop being dynamic.

We did a project with a Japanese eggplant called Kamo, a Kyoto heirloom vegetable that’s a really recognizable variety in Japan. For me, in central California, my main pressure is around heat and drought tolerance. I just love this eggplant, and my curiosity led me to experiment to try to train it to be more drought tolerant. We grew double the amount of eggplant that we needed for production that year and really stressed the plants with less water, no additional fertilizer, to the brink of where we saw a lot of the population dying, in the hope that what was left is offering something unique in ways that are greater than my understanding. I’m not a trained plant breeder, so I don’t fully understand the symphony of interesting interactions happening in the genetics, but I can still follow the plant’s lead by saving those seeds year after year.

Now, seven years later, we have something that can perform under a lot of deficit irrigation, and we don’t need to supplement even with compost. And this Kamo is as productive as the plants we coddled in those first couple of years. It’s heartening to see where we need to be, what our communities need to be resilient and thrive in more and more uncertain times, and to feel hopeful within that.

The farming practices we aspire to are collaborative—we’re looking at the net benefits over the long term for the most amount of life to thrive. It’s messy and hard, but in the philosophy of emergence, a beautiful synergy can happen when things in an elegant and complex system become more than the sum of their parts. Right now the farm is in its third season of operating more on the entropy side, where there’s a lot of work to keep the pendulum from swinging too far in one direction while finding an equilibrium. We might have certain crop losses while our production evens out, but we also see different kinds of rare pollinators and tree frogs! We see gopher tunnels because, without tilling the ground, a lot of different types of natural tillers start appearing. There’s a way that my farm has really made me sit with the discomfort and messiness of process, knowing that sometimes in change, you have to endure a little bit of heartbreak.

This has been a comforting lesson for me to hold in the bigger picture of the uprising we’re seeing now in the world. Everyone has to sit and ask, “What does shifting power look like?” When you can quantify what it means, you feel ready to do that work. As a farmer, I can quantify exactly what it means for me to prioritize the life of those frogs or the life of dragonflies and pollinators, compared to the money I’d make if I was farming more intensively or on a different scale.

A farm is a complete microcosm from which to observe everything that happens in the span of one season while working toward a bigger goal. It’s about learning and being humble and thinking collectively like plants think. In ecologies, there is a greater sense of interspecies collaboration and being adaptive. Most other life on earth understands that adaptation is the key to the perpetuation of a species.

In this moment of system collapse, we’re seeing people quickly iterating new systems and strategies for the world we yearn for in our hearts, while considering what we need to do on a practical level. We’re in a moment where prison abolition is part of the public conversation for the first time ever, but there is a reluctance for people to let go, even when we have the data that show the system does not work. The current justice system does not actually work to reduce crime or violence in our society, but it does perpetuate this other insidious type of violence. But, in order for people to embrace a possible change and really give room for their imagination to go wild, the alternatives need to feel infallible rather than giving ourselves room to just try other ideas.

We need to remember different cosmologies and ways of relating to this world. We need to look to leadership from indigenous communities. We need to start modeling and highlighting other ideas. There’s a reluctance to let go because it’s comfortable, even when we know it’s failing, even when we know it’s a suicidal tether to something that is not going to get us into the next 50 years.

My farm is situated amongst mostly big, conventional agriculture. It’s about mustering up inspiration and courage and always pulling the lens back to ask, “Who benefits from things being the way they are?” We know we have all of these different things worked out to make our food system function for one very distinct outcome, but we haven’t acknowledged a way to really value all those other things we talk about, like ecological health, health for our communities and the reduction of environmental violence.

We’re doing a CSA that centers seeds in a cohort for Korean, Vietnamese and Filipino American families in the Bay Area. It focuses on getting people to understand more about the plants outside of however they enjoy the product. It also operates on a horizontal plane where information benefits communities instead of remaining a static set of data or participatory research that funnels toward different gatekeepers in the community.

The theme of our first box was perilla. We had Vietnamese and Korean perilla, and it was all about sharing personal stories. For families who have kids who are ages four to ten, the kids have different objectives. They have to do an interview with each box to get workbooks and stickers. It’s about fostering both intergenerational dialogue in families or between communities because most of the Filipino families didn’t grow up knowing anything about perilla. But because the activities had a sense of citizen science, they listened and heard others tell these deeply personal stories about memories of their grandparents, or time they spent in Vietnam, and all the rich, deep, long histories that people have with that specific plant. It made all of these families super excited about perilla, even if it was less familiar.

For both young people and communities of color, often when we acknowledge public health disparities it focuses on deficits instead of really championing and lifting up the kind of cultural knowledge and assets within communities. How do we work from a place of what’s familiar and relevant to our lives, histories and things we want to protect?

Plants are another type of ancestor for us. When imagination is tethered to love, care and deep relationships, that’s when the possibilities become endless. To be allowed entry into this history and to then think about what you want to leave behind is an incredible position to be in. Specifically in this moment, given how wild the state of the world is, that kind of imagination is essential to fostering hope moving forward.