Pre-order your copy of SEEDS, MOLD Magazine Issue 05 here for a pre-order price of $18USD. Expected ship date is March 22.

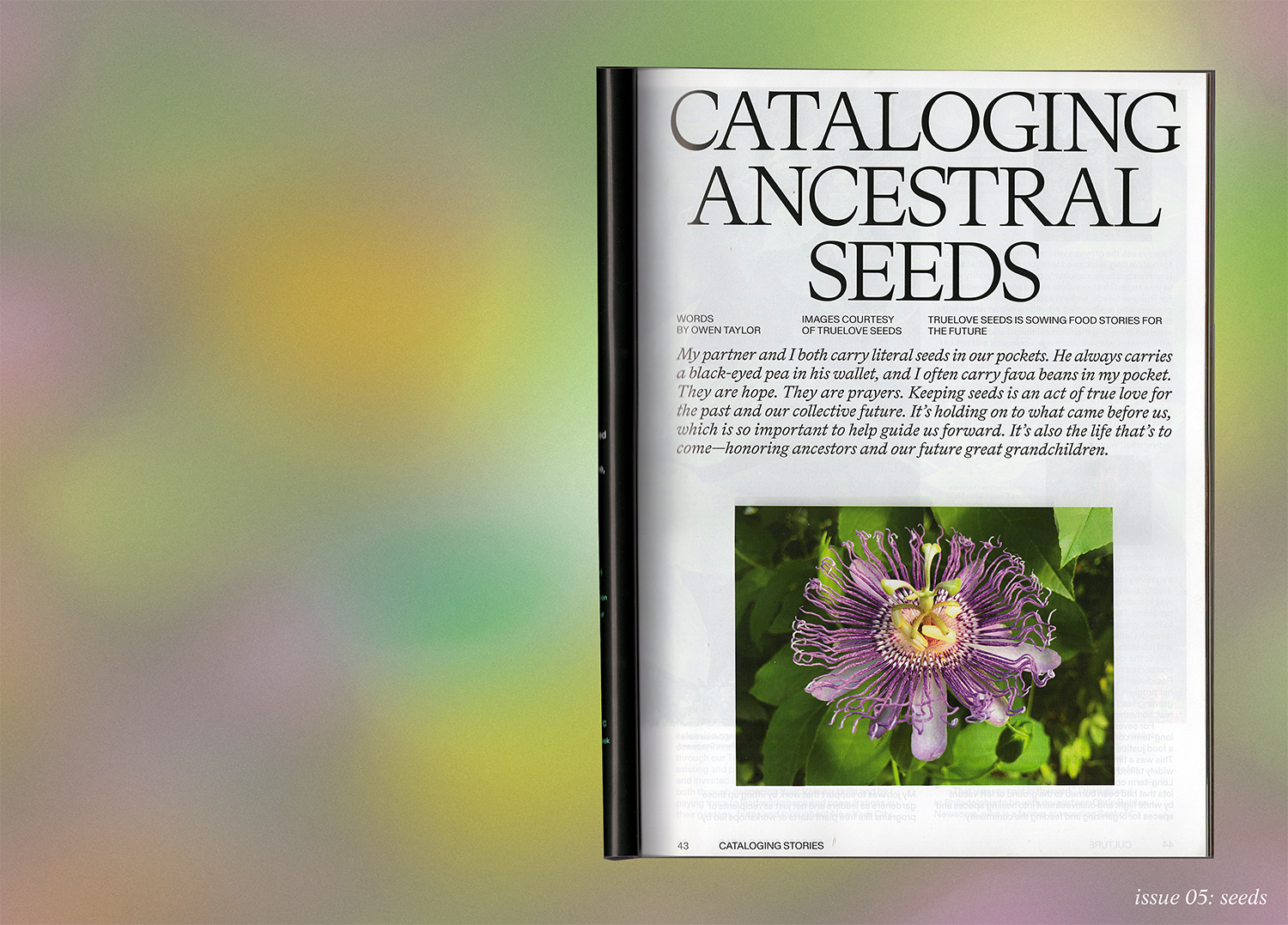

My partner and I both carry literal seeds in our pockets. He always carries a black-eyed pea in his wallet, and I often carry fava beans in my pocket. They are hope. They are prayers. Keeping seeds is an act of true love for the past and our collective future. It’s holding on to what came before us, which is so important to help guide us forward. It’s also the life that’s to come—honoring ancestors and our future great grandchildren.

I always ask the growers who are interested in growing for our catalog, what seed tells your story? What seed is connected to your ancestry, to your community work, to your region? Instead of curating a specific seed catalog for Truelove Seeds, we’re creating relationships with growers who are invested in building relationships with their food. We prioritize working with farmers who are invested in feeding their communities. I also only work with growers who are using agroecological and natural farming techniques. A lot of times these crops are grown in their traditional ways, if people still remember them, reaching back before the Green Revolution. We’re also working on a very small scale. Most of the farms we work with are just a few acres at the most, which lends itself to agroecological practices. They’re part of diversified farming systems where people are growing a few seed crops for Truelove Seeds but also growing a diversified vegetable farm for their community.

My work with food justice has always been rooted in the concept of environmental justice—that people of color and poor people are disproportionately negatively impacted by problems with environmental destruction and are also the best suited to lead the way in finding community-based solutions to these problems. This includes the built environment and access to food, green space, soil and land. I was introduced, through Cathrine Sneed and The Garden Project’s farm and job skills program at the San Francisco County Jail, to the idea of growing food as healing for individuals and communities who have suffered a great trauma. Recidivism is so much lower for those who went through her program, and she saw a transformation in people—growing food was a way to feel connected to something real, something meaningful.

For seven years I worked specifically to support long-term community gardeners with Just Food, a food justice advocacy organization in New York City. This was a time before urban agriculture was really widely talked about in public policy in the United States. Long-term community gardeners had been transforming lots that had been burned to the ground or left vacant by white flight and disinvestment into healing spaces and spaces for organizing and feeding the community. My job was to support that work by lifting up those gardeners as leaders and not just as recipients of programs like free plant starts or workshops led by extension agents and non-profit staff from outside their communities. My work was to amplify their voices through our Training of Trainers program. We identified existing and potential community garden leaders and invested in their abilities to share their expertise, both through deepening their training skills and by paying them to lead workshops and consultations in their gardens, farms and throughout New York City. Our Training of Trainers helped us collectively explore popular education and ask, “What is education for liberation? How do we lead workshops as agroecological, justice-focused practitioners for our community and beyond?”

That was my root in the work. I then moved to Philadelphia to be with my partner, Chris Bolden Newsome, who is a farmer co-running Sankofa Community Farm at Bartram’s Garden. I landed a part-time job community organizing around land sovereignty and needed more work, so a friend connected me with William Woys Weaver, the food historian, who’s been a seed keeper since the ’60s. He inherited, by mistake, his grandfather’s seed collection that was started in 1932. Through spending four years with him, hearing stories of the seeds and getting to know, intimately, these food and medicine plants—not just as food and medicine but as whole lives from seed to seed—I fell in love with seed keeping. I realized that this was where I wanted to spend my time and energy: learning these stories and learning these plants from seed to seed and sharing that with the food justice community.

At the same time, I had been introduced to the Seed Keepers Collective, which was inspired by the Indigenous Farming Conference in Minnesota. After the conference, Blain Snipstal, a farmer at the time with the Black Dirt Collective in Maryland, brought us all together and said, “Look, there are indigenous groups who call themselves seed keepers and focus on the stories and the rituals in the seeds. They’ve said: go home, find your people, do this there.” So he gathered people up and down the Mid-Atlantic to ask this question: What does it mean to be a seed keeper? What does it mean to hold the stories, rituals and histories?

With over 4,000 varieties in my mentor’s private seed collection, almost none of them were connected to his story as a Pennsylvania Dutch historian. I was like, “This feels like a museum.” It feels like seeds disconnected from the people and their land. I began asking: What would it look like to rematriate these varieties? What would it look like for people to be stewarding their varieties and not thinking of them as rare seeds anymore but culturally important seeds? For people who care about these seeds to grow them and keep them alive? Finding the answers to these questions was a pivot for me in deciding to focus on seed sovereignty and seed keeping.

Beyond the joys that I get from understanding the plant world so intimately that I can be a midwife for their next generation, for me, seed keeping has helped me rediscover my own Southern Italian cultural foods, my own Irish cultural foods. After a couple of generations of assimilation into whiteness in this country, it has been so deeply meaningful to start to think about where my grandparents came from. What was life like there? What are the foods that have been lost through the process of coming to this country? It’s a reaching back and a reconnection.

For the seed keepers who are more recent immigrants and refugees, it’s a process of holding on to something that everything is pushing them to let go of. It’s an act of resistance and an act of healing in that people still remember what their cultural foods are. They have such a hard time finding those foods unless they live in very specific neighborhoods in certain cities. The ability to keep those seeds is an act of healing in that it’s continuing to feed and nourish them and their future generations.

There are ways to look at seeds as metaphors. The fact that we plant this one seed and sometimes we can get thousands or tens of thousands of seeds from that one plant, really speaks to us about abundance and allows us to believe in abundance. So often we think of lack and loss. Keeping seeds is a hopeful act in that you can see that, by planting this one seed and caring for this plant and doing it in a community of plants that builds diversity and health, abundance comes from that.

Specific seed stories teach us about equity as well. Soul Fire Farm, who is one of the growers we work with, grows the Moyamensing tomato, which is from a prison in the Philadelphia area. A black cook from the prison kept these seeds in his family that were grown by the inmates. They lift up this tomato as a way to talk about prison abolition. There are ways to tell seed stories that inspire conversations around equity and justice. This year Soul Fire will be taking on the Plate de Haiti tomato, which has been grown by a children’s garden in Philadelphia, so that they can tell the story of the Haitian Revolution. That tomato was grown there up until that point, and then it was brought to the Philadelphia area.

People can talk about Resina Calendula, or just calendula in general, and how it was born by the resisters to the Nazi party in Holland. There are ways to lift up seed stories that speak to resistance and speak to resilience. I mean, when you look at Resilient Roots Farm, which is a Vietnamese refugee project, they hold on to the varieties that came over with the boat people, and they continue to maintain them in traditional ways, with traditional and innovative trellising, and they look to the elders to talk about how to grow and eat them. That’s looking at a seed story as resilience.

Plants also teach us how to help them procreate. If we’re really paying attention to the plants, we can see when the seed is ripe. We can look in there, break open pods, feel the seeds, and we get a sense of when that seed is ready to be planted again, or to be stored until future planting. This is a time when people need to listen to the plants so that they can be their own seed companies. They can go in the backyard and harvest the seeds for the next year.

With the demand for seeds, we are responding by growing as much seed as we can in addition to helping people learn how to do it themselves. People are coming back to the land and realizing that so many people struggle to access healthy, affordable food. It’s time to grow our own food. It’s time to grow our own medicine.