From MOLD Magazine: Issue 04, Designing for the Senses. Order your limited edition issue here.

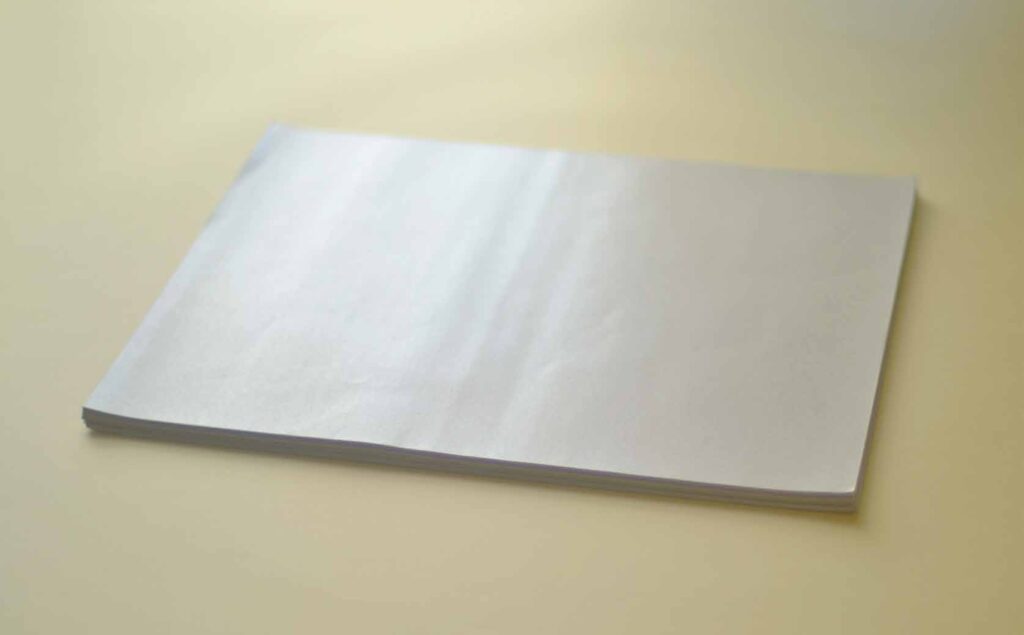

Tapow, derived from the Chinese phrase for “take-away,” is a common phrase heard on the streets of Singapore, where the consumption of takeout is almost an everyday affair. While it is common to find food wrapped in a flat piece of paper, some people are unsure what to call this type of packaging. Some call it “chicken rice paper”—as it is commonly associated with the local dish—or “kertas bungkus,” which loosely translates to “wrapping paper” in the Malay language. For the sake of clarity, we shall call this form of food wrapper with a water-resistant coating on one side tapow paper.

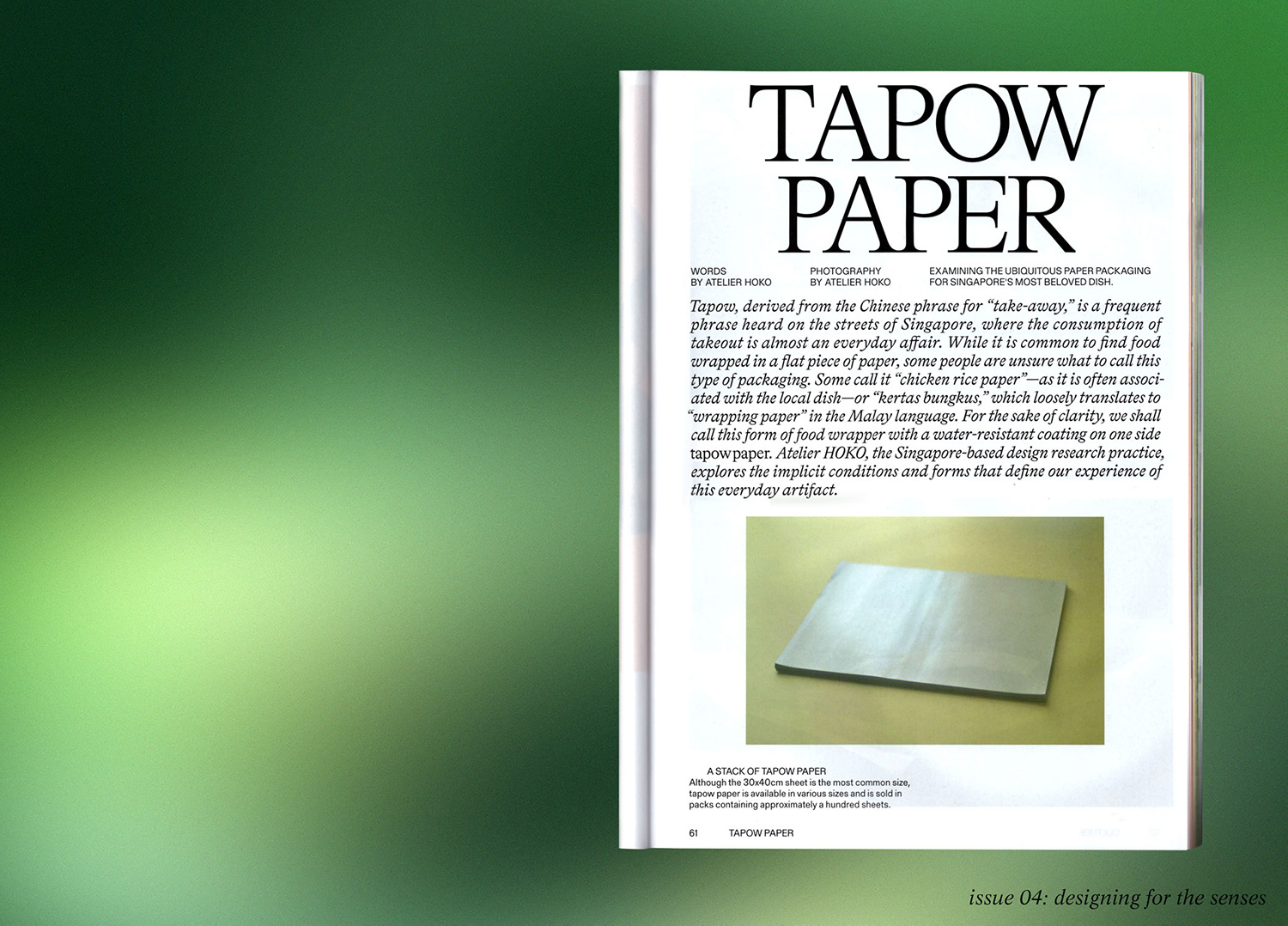

Images by Atelier Hoko.

Atelier HOKO, the Singapore-based design research practice, explores the implicit conditions and forms that define our experience of this everyday artifact.

Although the 30x40cm sheet is the most common size, tapow paper is available in various sizes and is sold in packs containing approximately a hundred sheets.

THE FLAT FINDER

In recent years, tapow paper has been steadily replaced by plastic or foam containers as many people lament the inconvenience of having to find a flat surface to support the structureless tapow packet when eating. Over-reliance on robust containers has consequently dulled our awareness of the surrounding environment—we no longer need to improvise or identify a flat surface that is “just flat enough” to eat from.

SLOWLY UNRAVEL

Not all takeaway food packaging is created equally. Some manufacturers take pride in how well their products seal and prevent spillage, some excel in presentation and effective compartmentalisation, while others emphasize eco-friendliness and biodegradability. Tapow paper, belonging to all or none of the criteria above, is concerned with something else altogether. Each step taken to unravel a tapow packet builds toward a sensorial encounter of the food inside, not unlike the anticipation of unwrapping a gift.

AN OPEN PLAN

For the uninitiated, the flatness of tapow paper may pose certain difficulties when moving food from surface to mouth. Such sentiments, typically felt by those who only know the manners of a table filled with an unnecessary amount of tableware and cutlery, are expected but can hardly be justified given the inherent versatility of tapow paper. Across South-East Asia, diverse, vernacular culinary practices have accumulated unspoken wisdom on making the tapow paper work optimally with the food inside.