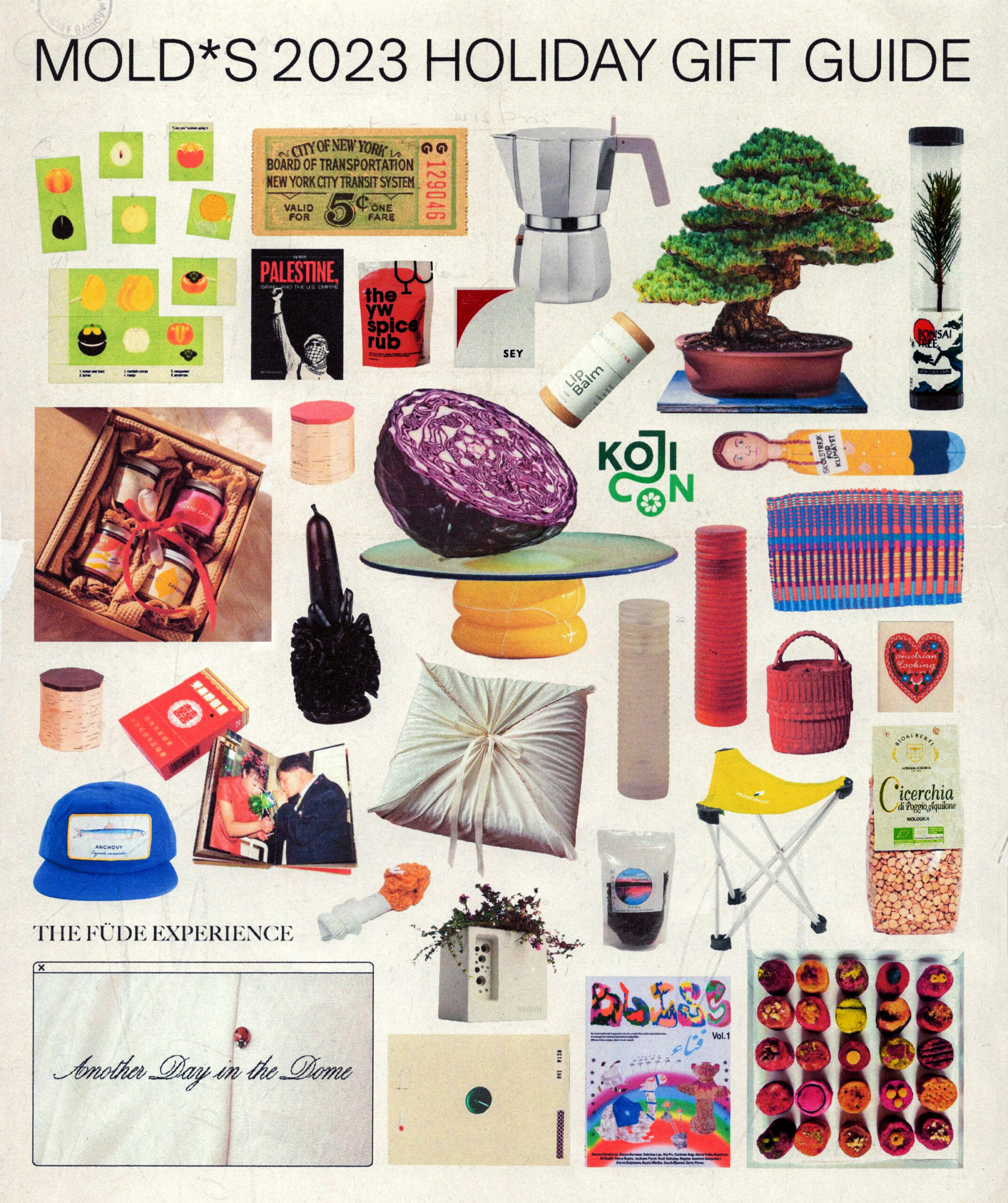

From its beginnings, MOLD has explored how we might design a more intimate relationship with food. The tools we use to gather, prepare, store and eat food actively shape this relationship. At MOLD, we’ve always published stories that have explored just how they do this, from the speculative—such as the design studio that created a climate-controlled dosa picnic basket to the man who created a taxonomy for bread tags— to the ancestral, such as one of the last craftsmen making mangtaeggi, or hand-woven farming tools, on Jeju Island. These tools are political, have material implications and link cultural identities. As a celebration of the creativity of MOLD’s community, the Food Tools Design Club is inviting readers to experiment, play, and submit designs for food tools through a monthly open design call.

Each month ahead of Summer Solstice, when MOLD will be transitioning into our next phase of digital archiving, industrial designer and ecofuturist Lily Consuelo Saporta Tagiuri will share a brief for designing a food tool. Reference images chosen by Lily and MOLD’s editorial team will be shared through MOLD’s Are.na. At the end of each open call, we’ll share out submissions with the community.

Brief 001: A Utensil for Eating

You are invited to design a utensil for eating your favorite food. We welcome material experiments, historical references and futuristic speculations. We encourage utensils specific to certain foods or locales, and tools that propose new modes of eating. Useful design always responds to a well-formed question. Some questions you can consider as you brainstorm your design: How does the tool enable feeling and memory? What is the material afterlife of the utensil — is it compostable? Edible? Meltable? Is it for someone who is eating alone or is it for eating in community? Can a utensil be a place-making tool? How can we reimagine the way we eat food?

Please submit your design here by April 2, 2025 including:

1-3 images of your tool (including one on a neutral background)

2-3 Sentences describing your tool

Medium of choice (No AI please!)

Your name

Social media handle or link to work

Perhaps the hand is the first utensil. Following this logic, all the tools that have followed since, were developed to behave like technical prosthetics. They allowed us to be more agile, to avoid getting burned or sticky, to hold liquid, and to grab small pieces of food. The earliest records of a utensil are of rock-based knives, a sturdier proxy for a fingernail. Then, there were spoons made of shell and bone that behaved like a cupped palm. These tools were followed by chopsticks, whose pointy tips act like more precise fingertips. Beyond these familiar categories of utensil there lie so many more ways to eat, like crafted wood sticks used to skewer foods or scooping bread like injera, or the government-issued plastic sporks in public school lunches. Seemingly simple and innocuous, utensils shape the choreography of how we eat, and are embedded within our belief systems, from wealth to hygiene, material to manners. As we collectively reconsider the utensil, we’ve collected a few examples from designers, artists and scientists who are reimagining how we eat through the tools we use to do so. -Lily Saporta Consuelo Tagiuri

What is the utensil for?

As a child, I was fascinated with Kenji Kawakami’s collection of books that illustrated a concept he had devised called Chindogu, or “unuseless designs”. The books are filled with inventions like a fan built into chopsticks to cool hot food as it’s being eaten or a hair guard against ramen noodle soup splashes. Although these single-use tools border on excess, they also manage to precisely address a design need.

In thinking of your tool, consider what needs you are meeting. For example, the OXO “Good Grip” peelers or Good Grip straps offer an option for someone with arthritis, who might have less mobility or require softer handles for comfort while performing repetitive motions.

What material is the utensil made out of?

When thinking about what materials you will use in designing your utensil, consider the sensorial experience it might elicit during the act of eating. For example, what would it feel like to use Meret Oppenheim’s furry teacup and spoon?

If the material makes the tool, how can we play with materials to challenge our conceptions of what a utensil is and what a utensil can be? Inspired by the phenomenon of synesthesia, Jin Hyun Jeon’s Sensory Cutlery collection invokes the spikey and gooey, playing with volume and temperature to impact the dining experience. How does

What is the context the utensil is being used in?

Some of our most innovative utensils are those that have been designed to help us adapt to extreme conditions like camping in the outdoors or outer space. When designer engineer Nikolas Grafakos recognized that astronauts can only eat food with a wet or viscous texture on their flights and designed a spoon that wraps around the food and could potentially allow them to diversify their diets. Utensils are tools developed in conversation with the context in which they are being used. How does your cooking environment shape how you might prepare food?

How can a utensil embrace the more than human?

Humans are not the only species to use utensils, maybe you have seen the videos of otters and their favorite rocks that they store in a pouch under their armpit, the perfect tool to crack oysters open with their soft little paws. What does it look like to design a utensil for the nonhuman?

In their project Refuge for Resurgence, Superflux Studio did just this, imagining a dining experience for the “more than human” including animals like a fox, wasp, cow, wild boar, snake, beaver, wolf, and a mushroom. This speculative work included cutlery for each creature and foods that they might each such as wood for the mushroom and a small egg for the snake.

If we zoom in even further to the level of the microbe, the kitchen and the dining room can be home to a crowd of non-human actors. In her 2017 project, Mother’s Hand Taste (son-mat) the artist Jiwon Woo, examined how the unique micro-flora growing on hands impacts the taste and properties of food. Focused on the fermented rice drink, makgeolli, Woo created a machine that allows people to cultivate their own micro-flora and dispels ideas about using our hands to eat and cook

For further inspiration, check out the Food Tools Design Club are.na: