Households in India come in all shapes and sizes, inhabited by varying combinations of grandmothers, nieces, uncles, aunts, mothers, fathers and everyone in between. They can be found in cramped alleyways or wide open fields. They’re filled with the quiet blessings of multigenerational objects – tools, containers, cutlery and decor used over and over in a culture deeply shaped by tradition. These utilitarian objects are designed by lineages of craftsmen shaping their trade with the advent of globalization and national development. While they often go overlooked within mainstream discourse around Indian design and its aesthetic identity, Tiipoi, a product design studio based out of Bangalore, is nurturing artisanal craft at its roots and using design thinking to harness the innovative potential of India’s manufacturing present and future.

Images courtesy of Tiipoi.

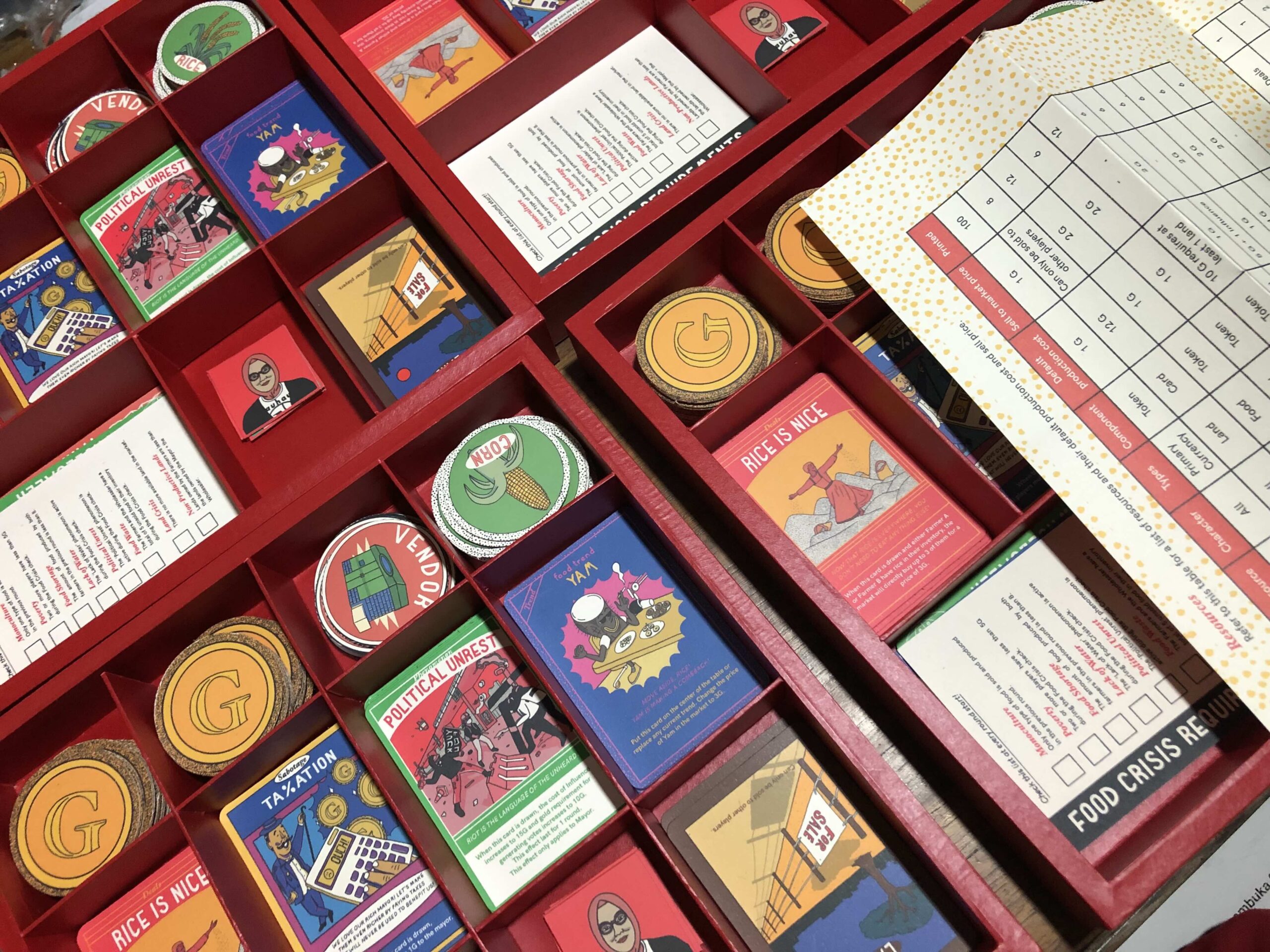

MOLD sat down with Tiipoi’s Spandana Gopal, who founded the studio in her grandfather’s old factory, for a conversation on India’s current design landscape, its global identity and how Tiipoi does things differently. Gaining a global following through their thoughtfully designed cooking ware, Tiipoi has become a vital contributor in the conversation around a South Asian cooking process based in cultural integrity and trade equity. They partnered with the equitable, single source spice trade Diaspora Co. to launch the Masala Dabba, a brass container filled with the essential spices needed in South Asian cooking.

Diaspora Co. centers integrity in a meticulous cooking process, which is arguably at the heart of South Asian cooking. For so long spices have been a trade commodity that have defined the economic possibilities of India, but for the people of the subcontinent and beyond, the way we use and revere those spices is woven into our lifestyles in subtle and understated ways. South Asians living in Canadian suburbs buy spices in bags and keep them in jars in a cupboard close to their stove. The jars might be thrifted or found at the dollar store. In India, this material experience varies on a scale. Those furthest from North American suburbia organize themselves in accordance to tradition. This means using the materials our ancestors used in a time before mass manufacturing, and often times before colonization. The masala dabba is the perfect example of this. It’s an object, specifically a container, that acts as an organizational tool and has held up as a widely used system of organization for centuries.

Granted it’s not very meticulous and highly user shaped, at the heart of it, a masala dabba is a metal box that contains smaller containers of commonly used spices. It’s in a box and not a cupboard because in the past, spices were gathered and distributed by individuals within their communities. New brides would be given masala dabbas by their mothers as a helping hand in adjusting to their new lives within new homes. Oftentimes it would be the same dabba, that same enduring metal, her mother gave to her a generation ago. The reverence given to spices and the utilitarian nature in which they’re handled across the sub-continent holds a lot of integrity. This is embodied perfectly in the masala dabba.

The collaboration between Diaspora Co. and Tiipoi did a good job bringing that to the forefront and centering it within the design process.Through re-envisioning this household staple, Tiipoi has reoriented the dialogue around Indian craftsmanship from an archaic perspective rooted in conservation to a forward thinking space as the foundation for innovation and design.

Hiba Zubairi:

Tiipoi champions its production process as a part of its design methodology and brand identity. How does this thought approach come to life in your factory in Bangalore where all your items are made?

Spandana Gopal:

It’s quite difficult to separate the design from the production. What we end up doing differently is we make things using craft-based production processes. It’s different from having a plastic molded chair which can be made in any factory in the world. Western designers and design brands do not have a practice of revealing where something is made within industrial design. Craft itself has a very different DNA in the West versus everywhere else in the world, where it is much more rooted in how people live. In India, it’s even more nuanced because people are born into certain craft identities. You’d be born into a family of weavers or metalsmiths. Craftspeople in a Western context versus a non-Western context can’t be compared; they’re like apples and oranges.

It extends into understanding who the craftsperson is – someone being viewed as an artisan versus someone being viewed as a laborer. For us we wanted to reveal these nuances rather than hide them. We wanted to take a position that was anti-nostalgia. This idea of conservation comes from a colonial narrative. When you look at the British idea of conservation its very different than India’s. In India old is seen as old, something new is seen as new. People are not apologetic when an old building comes down. We can say this is bad or good, but its reality, regardless. With Tiipoi, I did not want to hide the space of the workshop just because it was not a pretty space. India is known for textiles mainly and everything else is hidden away. Textiles on their own are beautiful and extremely aesthetic, the production processes are very photogenic, very Instagram-able. You can talk about natural dyes, hand dyes, see people working from home.

When you talk about anything outside of textiles, such as metal, the space is a lot grittier, darker, the work is more labor intensive—the coming together of hand and machine. And they tend to happen not in idyllic villages, they happen in cities. People don’t like talking about that because they consider it too dirty or dark. There’s an apprehension when talking about something being made when these spaces don’t look like what we think they should. We have this oriental gaze around how things are made and where they come from. From the beginning, our designs weren’t just about making something easy to make by a craft process. We chose very challenging techniques. What happens when industrial design meets craft? I think we need to appreciate and value the reciprocal relationship between the hand and the machine, and not fetishize the Indian hand.

HZ:

I feel like if anything is Indian it needs to be aesthetically pleasing to hold any value in the global eye and I think that plays into us hiding certain parts of our lifestyle because we don’t think it pleases people visually. Even though it’s a part of who we are and where we come from.

I’m from Lahore and the Old City there is filled with people who make knives, scissors, tools – these very large items that are interesting to look at but not made in the most beautiful settings. And these crafts lay at a juxtaposition to the crafts we experience living in the West. That contrast is a marvel and it’s really what you highlight in your work which is really special.

SG:

I feel like now, in the current situation, it’s important knowing that all metalcraft in India comes from the Mughal era through the king’s patronage. So when you think about textiles, inlay work, metalsmithing, all of these crafts came from the Mughal period and it was the monarch’s commissioning of artisans that provided them with space and funds to create and further themselves. It was about the exchange of knowledge. People don’t think about this diversity. All the best block printers in India are Muslim. We forget.

It even brings back that idea you were talking about of people’s perception with old vs new. What do we consider indigenous vs what we consider foreign. As soon as we start going back and looking at our history, especially in India where there is so much diversity and exchange between regional cultures, you can no longer draw that line of this is ours and this is yours. It’s such a responsive cultural landscape but when you apply that colonial framework of this is India and this is foreign it reduces that reality.

When people think of India, they think of things made by hand in primitive environments but that’s not the truth of it. It limits how you can appreciate a craft or the manufacturing process of an item. It almost doesn’t allow for it to be a designed object, it keeps it in a regressive framework.

SG:

Thinking about somewhere like Japan which also has an intense craft tradition, there’s this Western appreciation with Japanese craft and a perceived sacred quality to those spaces—there is a meticulous tradition which has been passed on. But again, when you think about the Japanese attitude to conservation—its very different than the English attitude. In Japan, shrines are taken down and rebuilt every 20 years in the same materials. This has been done for hundreds of years. The boundaries are blurred between the ideas of old and new.

HZ:

One of the interesting aspects of your design methodology is that Indian crafts should not need to chase or preserve the past to be considered valuable. What value do you find in the different crafts around India and how have they influenced your design thinking? You talked about how you can’t separate design from design production, what brought you to this thesis?

The brief we ended up giving ourselves from venturing into working with craft was, “How do you scale up craft?” Textiles is one of those crafts that has seen scale and volume but as soon as it goes into products you have two ends of the spectrum. You have very cheap product which can be found at flea markets for 2.50 GBP but was made for 20 cents. Those factories are grim. If you take a town like Moradabad, where Tom Dixon produced a lot of his products, no one has probably ever seen an image shared by that brand of what their factories or workers look like.

It’s very similar to the colonial working model, where you have the person at the top who owns the factory, then you have an agent and a network of metalworkers, spinners or sand casters, and they’re all working in tiny rooms, squashed in with one another in some back alley. It’s very efficient because one shop will do one activity and pass it along to the next. It’s not about “working bare feet.” (Which many may look upon in pity by assuming it is a result of poverty or primitiveness.) Indians will work barefoot even if they were in Japan. It’s not about that image. It’s the attitude towards that kind of work. It becomes no different than working in construction or being a bricklayer or doing any sort of hard labor. Are these people able to see themselves as artists, crafts persons and designers? No, not at all.

Coming back to my Moradabad point. I had this space which was my granddad’s old factory which was producing something completely different than what Tiipoi became. They were using industrial ceramics. I started taking over bits of the factory. I thought, “Wow, this is really cool. Why can’t we all be under the same roof? That industrial and craft aspect.” And that’s what it became. That’s what the team is now. You have Sasa and Venky who do handmade pottery and metal spinning. The atmosphere was of an industrial space. It’s in an industrial part of the city. But it’s clean. It’s legit. We have T-shirts that say where we work. Why can’t it be that? Why does it have to be either extreme?

We find ourselves in a middle space. We’re not selling cheap products. Neither are we selling things you would only find in art galleries or in designer shops. That’s where we are and I am advocating for this middle space.

HZ:

Material takes such a central role in all your products, from Ayasa Copper to Longpi collection of ceramics, even to the concrete water-tower planters. You specify the exact region where the material is used. How do you go about choosing these materials? What stories do you look for in it? Or is it the other way around, where you have a story and then you search for the materiality within it?

SG:

For us, we look at the problem we are trying to solve. With the brass and copper products we were trying to see how to integrate these materials into everyday objects, such as storage jars or simple kitchenware. We wanted to use brass and copper to bring those materials into the spaces it traditionally has in an Indian home, such as the kitchen.

With Longpi we were celebrating that material. We wanted to take it from a rudimentary but beautiful simple form that you find in an airport shop into something that could be a usable and functional design you could rely on and cook with. It was all about celebrating the Longpi material for what it was. Which is why we haven’t done anything else but cooking pots because we wanted the purpose to stay true to the original function of Longpi pots. It’s what they use to cook on an open flame. What you see is people get excited by a new material and make anything and everything out of it. But Longpi is unsafe to eat off of, but cooking off of it is a different story. For us, it is really important for the products to have design integrity.

HZ:

The cooking ware is made through a really beautiful metal spinning process, especially the Masala Dabba and your brass products. You documented this on your blog and spoke about how it takes 72 minutes to make one Dabba (box in Hindi). The process in its meticulousness and care aligns pretty perfectly with the values of Indian cooking. Within Indian cooking, the ingredients somehow remain the same but small changes here and there make a huge impact on the dish itself. Within Indian cooking, what processes and values do you want to give meaning and integrity to through your products?

You have the answer to your question. There’s a certain ritual and methodology in cooking. A certain knowledge that is inherent. But often this knowledge is bastardized or appropriated in a way that does it a disservice. I’m not anti-appropriation. I think appropriation can be a good thing if it comes from an authentic place. Sometimes those things get lost along the way. I’ve seen masala dabbas used as storage boxes for trinkets.

There is this copper water bottle trend these days. Which disregards such a particular ritual. You cannot just fill a copper bottle with water and take it to spin class. It’s just not the same thing. There’s a certain procedure around how many hours you can keep the water in the glass, you have to empty the water, you have to look after the vessel itself, you drink it first thing in the morning. It’s very easy to put out some copper glasses, lots of Indian brands do it. But it’s a metal and it’s going to have a reaction with food and water. I’m selling this thing and people are going to consume it. Even with Longpi, with so many ceramic and stone vessels across India used for different types of food based on the specific chemical reactions that happen between the material and the ingredients.

In many ways, stainless steel is the best material to cook in because it is so inert. I love stainless steel and the way India uses stainless steel. We would love to design a thali next. When you think about the utilitarianism of the material it is staggering. The way the plates stack like nothing else. You can have tall towers of plates without even a slight tilt. Food tastes better on stainless steel and because of how we eat, you don’t have cutlery you need to collect.

That sort of design transition of eating off a leaf to eating off a thali is incredible. Both of those products mirror each other. One of those products is entirely sustainable, its compostable, it goes straight back into the earth, versus the other one is virtually indestructible so there is no waste. You can use it for a lifetime. You engrave your name on it and give it to your kids to use so they have something to remember you by. I love this mirroring of two vastly different products that end up doing the same thing.

HZ:

Especially living in the West, people think they can co opt parts of cultures and their cultural values by simply having aesthetic markers of it in their life and that’s just not how it works. If you look back to India, the way that people live and collect and eat and lead their lives, it’s just innately what the West considered sustainable. And it’s not because they’re motivated by activism or curbing climate change, it’s just the way we collect items, organize our houses and live with our families that results in sustainability being rooted in our culture. It’s not about aesthetics. That’s the difference between culture and consumerist appropriation.

SG:

Like, what is organic? What is eco-certified? It’s greenwashing. I’ve been asked at panel discussions how I ensure the health and safety of my workers, or how I ensure that everyone is above legal age working for me. I want to ask those people; how do you ensure these things? Is there a reason you’re asking me these questions?

There was a time where you had to seek approval from the industry and your peers, who are all white. Now I don’t care. I employ 15 people and I am able to pay them salaries on which they can afford to build homes and move forward within their own lives. And we have fun. That’s all that matters.

HZ:

What’s next for Tiipoi?

SG:

For me the struggle is how do I accommodate creativity within what’s otherwise a successful production strategy. We’re doing some exciting things with ceramics and Longpi to hopefully come out this year. Sasa, our potter from Manipur, is experimenting with new clays and went to wheel throwing lessons and wants to get a wheel in the workshop. I’m happy Tiipoi can help him grow creatively through his work. Venki is busy spinning. The Diaspora Co. collaboration was very successful which has resulted in collaborations with different brands. Venky is a busy man.