Consider this as you walk down a supermarket aisle: one in eight people in the United States do not have enough to eat. There are people facing hunger in every community— your neighbor, co-worker and the woman next to you on your morning commute. He is the child next to your son or daughter at recess or in school.

Volunteers pre-package surplus squash at City Harvest Food Rescue Facility in Long Island City, Queens.

Volunteers pre-package surplus squash at City Harvest Food Rescue Facility in Long Island City, Queens.

For 38 years, Feeding America, the United States’ largest hunger-relief organization, has been leading the charge to rescue food and get it to families who need it. In the last year alone, we rescued 3.3 billion pounds of food from going to waste (that’s more than 7,500 jumbo jets) and provided it to hungry families through our nationwide network of 200 food banks and 60,000 food pantries and meal programs.

The question remains, however, how can we do more? The reality of our economy today means food insecurity and hunger is persistent across the country. Last year in the United States, more than 41 million people had the experience of not knowing where their next meal would come from. Add the growing health crisis we’re seeing, and eating a nutritious meal becomes even more urgent.

City Harvest rescues and delivers 160,000 pounds of food each day with a fleet of 22 refrigerated trucks deployed from their 45,000 square foot facility.

City Harvest rescues and delivers 160,000 pounds of food each day with a fleet of 22 refrigerated trucks deployed from their 45,000 square foot facility.

This year, in partnership with The Rockefeller Foundation, Feeding America explored ways to increase peoples’ access to fresh, nourishing produce by innovating our charitable food distribution models. But moving from the traditional food banking model of boxed pastas and canned vegetables to having perishable foods available to people more reliably requires a shift in the capacity of our food banks and our food pantries.

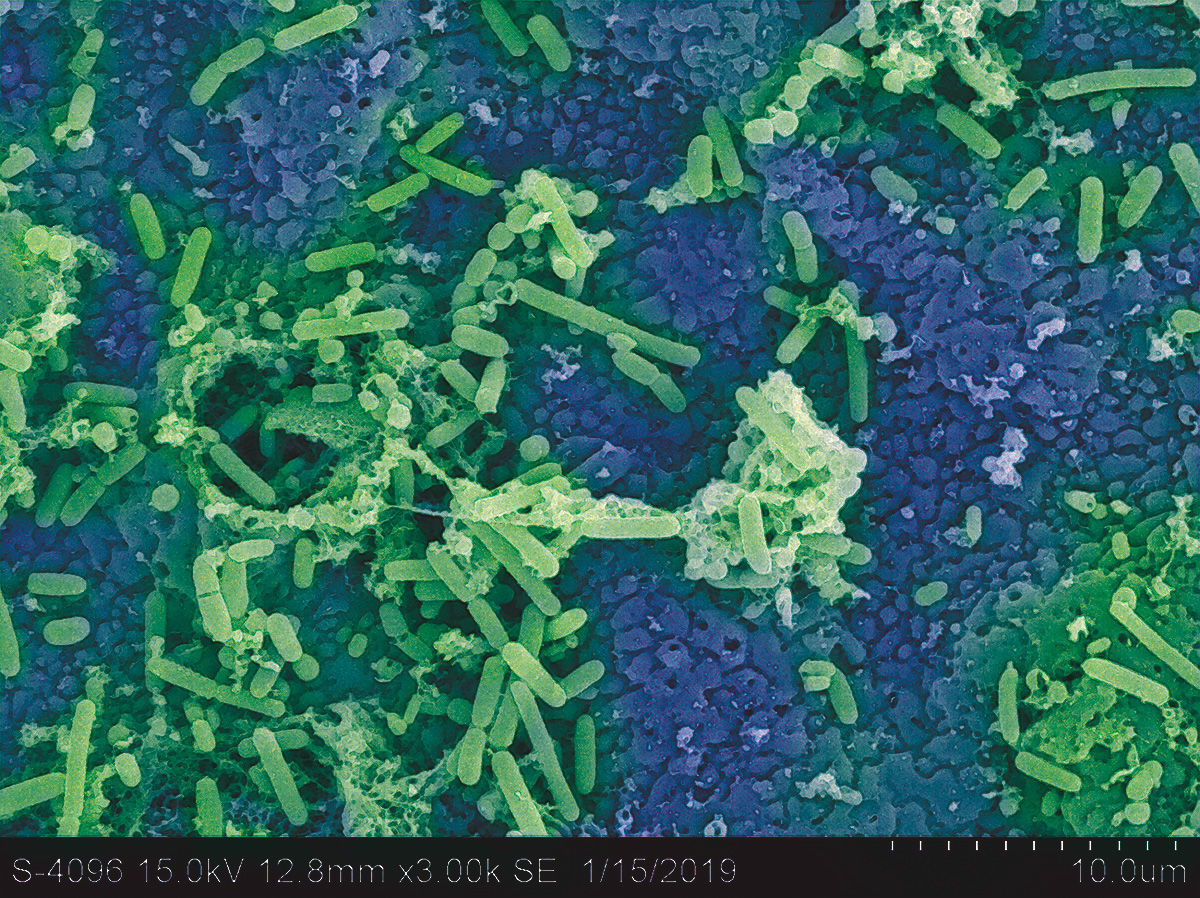

Because fresh fruits and vegetables are perishable, food banks, food pantries and meal programs face challenges in managing the costs of distributing produce quickly and often over long distances. Through research and concept development with a food bank in our network, Feeding America’s innovation team uncovered two key findings. Limited availability and inconsistency made it difficult for food pantries to predict what produce is available and when. This not only makes it challenging for food pantry volunteers to plan for storage and distribution, but also results in pantry patrons having a low expectation of getting fresh fruits and vegetables from their food pantries. Secondly, as with any busy family, we found that knowing how to plan and prepare healthy and satisfying meals using fresh produce is a challenge.

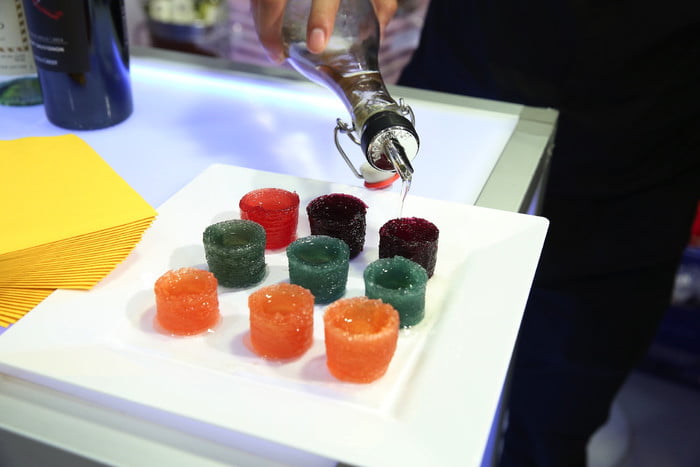

With these insights, we developed and tested two concepts for making fresh produce more accessible—both in food pantries and at home. In our first concept, called Side Car, pantries order the quantity and kind of produce their patrons request and have it delivered just in time for their scheduled food distribution. This service eliminates the need for storage by immediately repacking produce into display crates and delivering them directly to pantries using optimized distribution routes. By serving pantries as nodes within a coordinated network using trucks on an optimized route, we connected pantries with a service they hadn’t been able to achieve as independent units. This service is an innovation of our network structure, product and customer experience.

The second concept, Now & Later, mobilizes local chefs to prepare family-style meals at program sites using only fruits and vegetables from our local produce cooperatives. Families were invited to enjoy a delicious meal made from local chefs using regional produce, in a welcoming and hospitable environment. At the end of these dinners, families were given the recipes, prep tips and ingredients needed to cook the same meal at home. Programs like Now & Later are not only social experiences in hospitable and inclusive environments, but they provide an opportunity for people to understand food and its nourishing potential for themselves and their family.

Now that we’re able to manage more diverse donated products including perishable foods, we’re starting to consider the user experience. What does that actually look like at the touch point of the end user? What are our users’ preferences? It’s not one-size-fits-all: we have cultural preferences; we have dietary requirements; we have time and access points that we need to think about differently.

We must also continue learning how much fresh produce availability impacts our charitable food network and people facing hunger. We are exploring further questions including: How much of these fruits and vegetables wasted once they reach food pantries or people’s kitchens? Will these efforts affect the health of people facing hunger or increase their consumption of produce? How might we create health partnerships and alternative access points?

This year, City Harvest will collect 59 million pounds of food from farms, restaurants, grocers and manufacturers to help feed nearly 1.3 million New Yorkers.

This year, City Harvest will collect 59 million pounds of food from farms, restaurants, grocers and manufacturers to help feed nearly 1.3 million New Yorkers.

As we think about transforming the charitable food model and our organization to be more user centered, we need to measure impact beyond pounds of food recovered. Instead of measuring truck loads, a new metric might consider the right variety, quality and quantity of foods. That’s not about pounds, that’s about making sure that people have access to a mix of food that is high quality and nourishing, both to the body and soul.