On a neglected side street in Mexico City’s bustling Downtown Cuauhtemoc district, tour buses pull past an unmarked doorway to disgorge passengers into the lobby of a tourist hotel. Unbeknownst to them, some of Mexico City’s most innovative food is being served from the neighboring restaurant with no name. Behind the frosted window panes, a cook greets customers while overseeing the house specialty—an earthenware olla of slow-cooked beans and tortillas pressed at a steady clip to fire on the traditional comal. Here in Chef Sofia Garcia Osorio’s open kitchen, the ingredients are locally sourced and the cooking is inspired by artisanal production, culinary traditions and nostalgic flavors from an unhurried past.

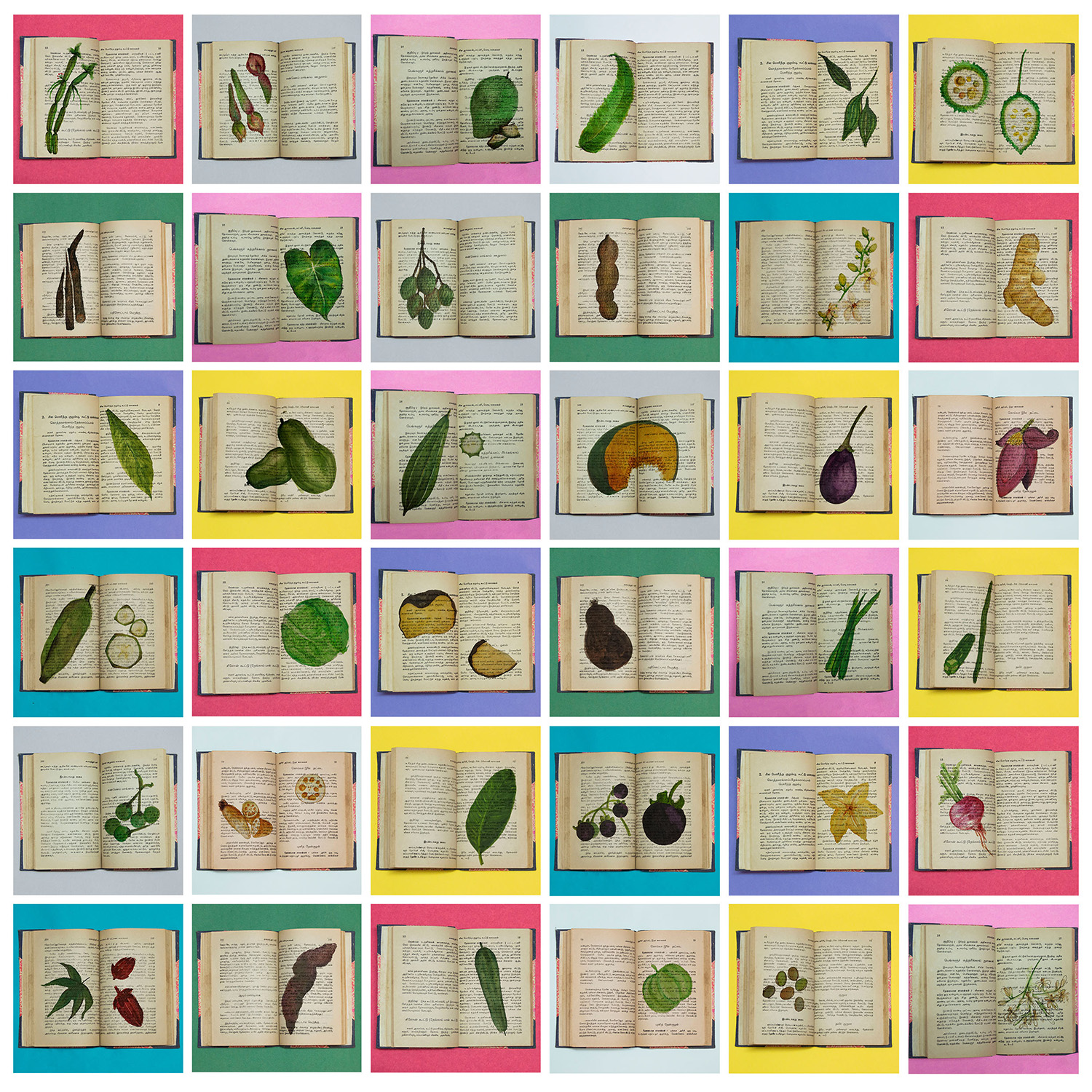

Chef Sofia Garcia Osorio with a selection of herbs used at the restaurant

Chef Sofia Garcia Osorio with a selection of herbs used at the restaurant

“You used to tell people about a place by saying, ‘Oh, its right across the street from that big tree.’ We’re playing on that old way of doing things,” Garcia explains. This ethos influences both the decision not to name the restaurant and Garcia’s holistic approach to food. In this sliver of Mexico City next door to the famed mezcal bar (and sister business) Bósforo, Garcia recreates the flavors of homecooked meals enjoyed in the smaller villages outside of the capital. Going against the urban impulse for faster, cheaper, more efficient food, the dishes served at the restaurant have the warmth and depth of flavor that only slow food techniques could impart on a meal.

Garcia’s approach to food is most easily understood through the story of tortillas: “It’s not just handmade tortillas, but we prepare fresh nixtamal and we grind corn for masa every day.” Most people today eat store-bought tortillas, but the process of making this staple of Mexican cuisine is ancient—archaeologists have found equipment for nixtamalization dating from 1200–1500 BC. Over the course of two days, corn is soaked in an alkaline solution to create emulsifying agents, allowing dough to form when the kernals are handground into masa using a stone metate slab.

The metate, used to grind corn into masa, is positioned prominently in the restaurant

The metate, used to grind corn into masa, is positioned prominently in the restaurant

Corn is sourced from different regions through different channels for the restaurant—when we visited, the corn is from Mexico State but experiments were in the works with corn from Oaxaca. The team was also investigating corn from Veracruz, where Chef Garcia is from, as well as Morelos. “Different kinds of corn require a different process for nixtamal and they produce different kinds of tortillas.” Whether its through the Chef’s own travels or through associates, sourced from Mexico City corn markets or directly from producers, the process requires patience. “When we travel we ask people where they get their corn, they’ll give us a contact, and we’ll seek out people until we find the right place.”

This penchant for connecting directly with producers is also evident in the tableware. Each course is served in a rustic, unglazed clay dish. When working on the concept with Arturo Doza, her business partner and owner of the sister mezcal bar Bósforo, Garcia began to research cooking tools and tableware for the restaurant. Barro, or clay, is an important material for Mexican cookware as it transmits and retains heat differently than contemporary steel pots. After sourcing pottery from Guerrero, Oaxaca, Veracruz and other states, Garcia decided the techniques and design from Los Reyes Metzontla in Puebla fit the aesthetic and culinary needs of the restaurant.

“In that community, everyone makes this kind of pottery,” Garcia explained. “The shine on the exterior comes from polishing the dishes with a small river stone.” When approaching the cooperative of artisans from Los Reyes Metzontla, Garcia identified which styles made the most sense for her menu as well as the appropriate dimensions of the plate in relation to the dimensions of the table. She then commissioned a run of 50 pieces to be made by hand from a specific artisan. “We just ask them to make something similar to a design they already have. It’s a slow process because they’re not used to making so many pieces of the same plate. Now that we’re adding some new dishes to the menu, we need to go back and find new plates for the new menu.”

An earthenware olla for cooking beans and the comal are centered in the restaurant.

An earthenware olla for cooking beans and the comal are centered in the restaurant.

The same barro is used for the olla and the comal. It’s not a coincidence that the house specialty is a revelatory version of a humble staple served in every Mexican home. Homecooking in the city is dominated by convenience foods and convenience preparations. Here at the restaurant, the beans are stewed for at least six hours and the tortillas are crafted with care from kernal to comal. The comal is the center of Mexican cookery and occupies a central place in the restaurant. Not only is it used for tortillas, but also for roasting tomatoes, chiles and drying herbs. “It’s an indigenous way of cooking, without frying, focused on roasting or steaming,” Garcia tells us. “The comal is important because that’s how you get flavors from a lot of our ingredients, cooked slowly, over time.”

After graduating from Universidad de Claustro de Sor Juana’s prestigious Mexican Gastronomy program, Garcia went on to cook in a number of high profile kitchens and hotel restaurants in Mexico City’s luxe Polanco district. From there, she became an in-house chef for a huge agribusiness’ frozen food vertical, creating recipes with chefs and owners of hotels and restaurants that made up the business’ customer base. It was in this role that Garcia develop her own philosophy around food. “I saw the way food was actually being handled,” Garcia said. “This company was focused on how to make food more efficient, saving time, making it work with less people.” In this industrial food context, Garcia decided that it was important to honor good food with considered cooking—artisanal production methods that can experiment with locally produced, high quality ingredients, and a human hand to bring out those variances in flavor.

One example in how this approach works in the kitchen is how Garcia and her team treat herbs. There are a lot of typical herbs used in Mexican cuisine but Garcia often sources herbs directly from producers. Taking an avocado leaf from a container, she encourages us to take in its flavor. It doesn’t smell of anything. She then pulls out another leaf, this one has been dried on the comal at low-heat for hours. The dried leaf has a distinct floral aroma, not unlike anise. It is a staple herb used in the house beans and like with most ingredients, the team doesn’t hesitate to experiment with the herbs used to impart flavor to their dishes.

“With the internet and smart phones, people have lost the ability to go on a recommendation by word-of-mouth,” Garcia laments. “If you don’t have a name, you aren’t part of the system. Instead of checking in on an app to see pictures of a restaurant, you can focus on the meal and flavors.” With Garcia’s slow food approach to Mexican gastronomy, she is cultivating a community of producers, artisans, cooks and diners that value time through flavors and a shared culinary and historical experience. “A big part of the history and value of Mexican culture is in its food—we’re just trying to maintain it and transmit it.”

Menu changes seasonally. The restaurant is located next to Bósforo, Luis Moya 31, Cuauhtémoc, Centro, Mexico City