On a recent foraging trip in Oklahoma City, cook Celeste Baca searched for honeysuckle and wood sorrel with me while lamenting some Oklahoman’s palettes: “it’s a steak and potatoes kinda state”.

As a born-and-raised Oklahoman, I am quite familiar with the type. But Oklahoma City is beginning to give this rumor a run for its money with its restaurant scene, which now boasts a number of ambitious food establishments. A more global buzz about what’s going on there as of late has Nonesuch largely to thank, a 20-seat restaurant in the city headed by Colin Stringer and Jeremy Wolfe that was awarded “America’s Best New Restaurant” by Bon Appetit in 2018. To emphasize just how unexpected it is to find something this sophisticated in a middle America town where you’re more likely to find chicken fried steak than chicken liver mousse is best summarized by the restaurant editor Andrew Knowlton in his Bon Appetit piece on Nonesuch: “I was head over heels but utterly confused. Who cooked this dish? And what the hell was this place?”

Photo by Allison Fonder. Chef Colin Stringer giving a lesson in foraging.

Photo by Allison Fonder. Chef Colin Stringer giving a lesson in foraging.

Nonesuch stands out for its non-coastal locale paired with the chefs’ dedication to using only local ingredients in surprising, experimental ways. Given Oklahoma’s extreme seasons and unpredictable weather patterns, this turns out to be no easy feat. I was told on my trip that the chefs had worries about the restaurant surviving through last winter due to limited resources, which sounds like a completely alien concept in our current Amazon-laden world where access is guaranteed 24/7. In fact, much of what Nonesuch does feels like a revisiting of our basic roots, a primordial age, in that doing what they do requires a deep understanding of seasonality and thorough field knowledge.

Photo by Allison Fonder. Wild carrot greens, aka Queen Anne’s Lace.

Photo by Allison Fonder. Wild carrot greens, aka Queen Anne’s Lace.

Which brings me back to foraging—I was lucky to join the chefs on a morning trip to the wildlife refuge in town where they gather ingredients on a weekly basis, a practice based on indigenous traditions that began for Wolfe and Stringer about 5 years ago during their days running Nani, an under-the-table dining club they hosted in Stringer’s home. Foraging in Oklahoma can be surprisingly abundant, but its treasures require a trained eye and vast knowledge of prep and preservation techniques. While poison ivy was just about the only thing I was keeping an eye out for, Stringer and Wolfe introduced me to plants I would never trust myself to pick up and taste. A forest I previously saw full of abstract plant life suddenly transformed into an overflowing pantry. We tried mustardy-tasting flowers called ‘poor man’s pepper’, a broadleaf wood sorrel with an uncanny citrus taste, and miniscule yet delicious wild carrot flowers, also known as “Queen Anne’s Lace.” “I love when [Queen Anne’s Lace] flowers cause this [happens] like one week of the year,” Stringer mentioned during our walk, “they’re really sparse.”

Photo by Joey Rubin. Green garlic custard with spring alliums.

Photo by Joey Rubin. Green garlic custard with spring alliums.

It’s this element of chance, discovery and rarity that drives their menu choices and the speed in which it changes. “The menu changes slowly day to day, [and] it’s based off the ingredients we have access to. A lot of these ingredients have micro, micro seasons. We might only have blueberries for three weeks in one year, so it just kind of changes based off of what’s available,” said Stringer. I was told during the trip that spring is ideal for foraging thing likes onions, pear flowers and wood sorrel, and my visit to the restaurant that night reflected this in full. One of the standout dishes of the evening was a green garlic custard with an assortment of spring alliums, which made use of a wild ingredient that Wolfe earlier that day had told me was “rampant” this time of year (no pun intended). It’s a dish that’s startlingly delicious, and a creative idea that clearly comes into being when a limited ingredient list sparks inspiration. The wood sorrel appeared in a refreshing tea at the end of the meal paired with a macaron made from pecan flour, an abundant nut in the region.

Photo by Joey Rubin. Chef Colin Stringer serves up pecan flour macarons.

Photo by Joey Rubin. Chef Colin Stringer serves up pecan flour macarons.

But Nonesuch can’t just rely on foraged ingredients. On a visit to Prairie Earth Gardens in Oklahoma City, a modest two-acre operation providing the restaurant with sustainable local produce, the team told me more about the challenges of farming presented by “Tornado Alley’s” weather. For example, if it’s over 80 degrees Fahrenheit consistently at night, tomatoes in the summer won’t pollinate and fruit. Or if the ground is too wet, as it often is in the spring due to severe thunderstorms, potatoes can easily rot. “You can only grow for a certain period of time where in other climates you can grow for longer periods of time. So we use [time] windows to grow cooler crops, and then we move over to the warmer weather crops very quickly,” field grower Rod Krueger informed me during a tour of the Prairie Earth grounds.

Photo by Allison Fonder. Micro-greens grown by Prairie Earth Gardens.

Photo by Allison Fonder. Micro-greens grown by Prairie Earth Gardens.

The farmers in town are becoming more interconnected with the Oklahoma culinary community, and work with chefs in a way that feels more like a partnership. Prairie Earth founder James Pickel and his crew were asked by Stringer and Wolfe to grow non-traditional produce like micro-greens, bitter melons and toothache plant, a flower that numbs your mouth when consumed. Another farmer, Sammy Forbes, helps Nonesuch by growing plants uncommon to the climate like wasabi and citrus through painstaking methods. A local approach to sourcing ingredients doesn’t just demand an expert knowledge of the plants that grow around them, but also close relationships with the farmers who supply their goods.

Photo by Joey Rubin. Nonesuch’s chilled asparagus soup (pictured above is pre-soup-pour) with frozen yogurt is garnished with Prairie Earth Garden’s micro sorrel.

Photo by Joey Rubin. Nonesuch’s chilled asparagus soup (pictured above is pre-soup-pour) with frozen yogurt is garnished with Prairie Earth Garden’s micro sorrel.

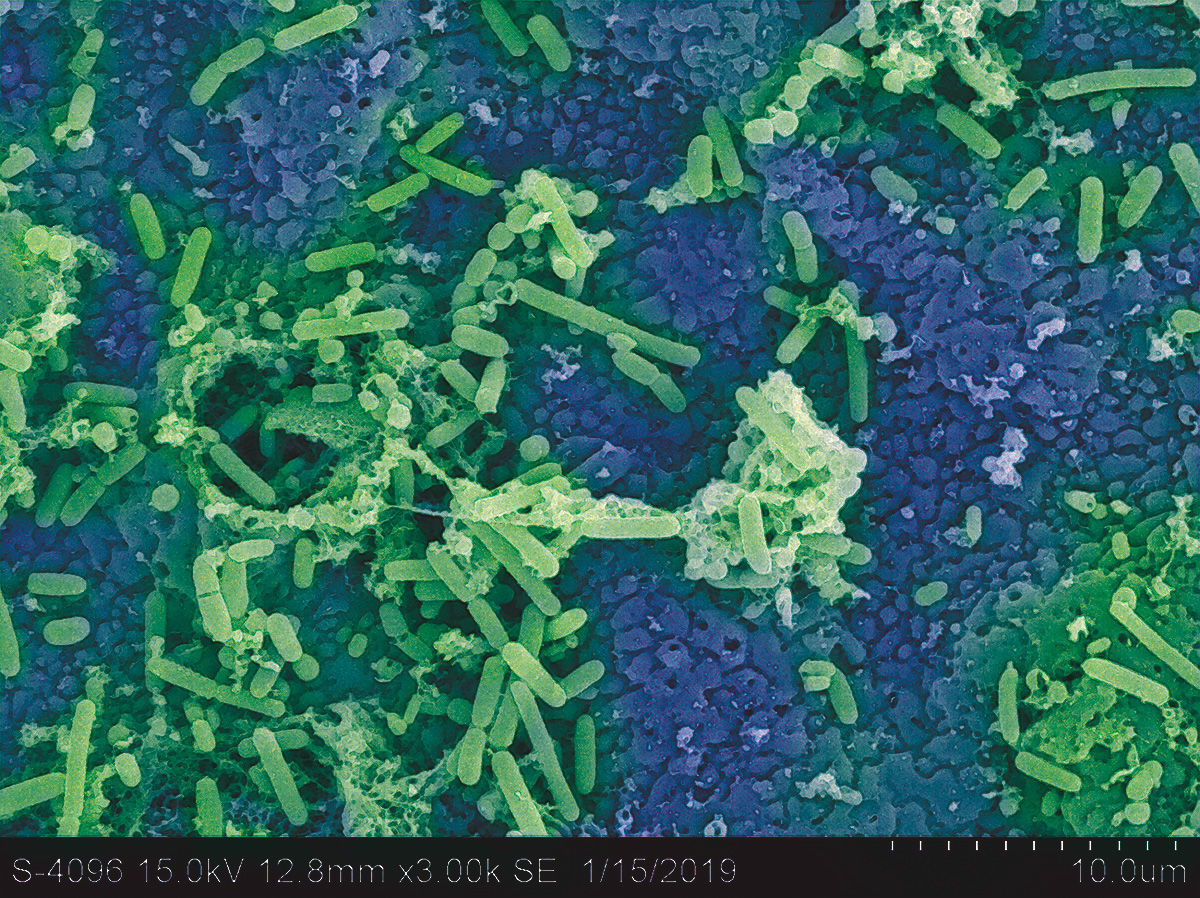

My spring visit may have been a bountiful time, but it still begs the question: how does Nonesuch manage to survive the winter? What’s not as obvious is how the chefs incorporate plants and mushrooms they find and preserve from past seasons. A little before my dinner reservation, Stringer invited me to the kitchen to see exactly what they do with ingredients foraged during their hunts. I was introduced to spices made using their dehydrators; diverse flavors such as nasturtium flower powder, fermented strawberry and dried persimmon climbed up the walls of the kitchen. The back room was filled with other experiments such as a preserved king oyster mushroom stock (which was perfectly seasoned, with a spot on umami taste that could beat most miso broths) and a morel mushroom amino, used to provide variety of dishes with rich natural flavor.

Photo by Allison Fonder. Under-ripe plums Nonesuch picks to ferment umeboshi style.

Photo by Allison Fonder. Under-ripe plums Nonesuch picks to ferment umeboshi style.

During our foraging trip, the chefs also pointed out different plants and what they tend to do with them. The poor man’s pepper mentioned earlier? This is typically dehydrated and made into a powdered seasoning. Stringer also pointed out a number of under ripe, tannin-rich plums we passed by, which they often salt-preserve umeboshi style :”we found if you ferment them for at least half a year, they lose all the bitterness.”

Photo by Joey Rubin. The first course spread at Nonesuch, including nasturtium flower with with whipped lardo and barbeque beets.

Photo by Joey Rubin. The first course spread at Nonesuch, including nasturtium flower with with whipped lardo and barbeque beets.

While the knowledge of what was foraged and used in their cooking gave me a further appreciation for how the ingredients were transformed into this 12-course meal, there remained an inexplicable, almost magical quality to how it all came together when I finally sat down for dinner. The first course was a visual feast of five amuse-bouche style dishes like barbecued beet on a carved-branch skewer and nasturtium flower with whipped lardo, followed by small dishes that came in one by one with a full explanation by one of the chefs or staff. The meal was a journey from light and crisp to smoky and substantial, with later dishes highlighting distinctly Oklahoman flavors like bison testicles (very tasty) and barbecue quail. Dinner ended on a particularly sweet note, not just because dessert was a blueberry sorbet, but also for the fact that blueberries’ short growing season meant this dish was likely just a blip on the spring menu. I savored every bite.

Photo by Joey Rubin. Barbeque quail dish at Nonesuch.

Photo by Joey Rubin. Barbeque quail dish at Nonesuch.

As it turns out, the elements of running a restaurant like Nonesuch that end up being the most challenging also seem to be its greatest selling points. When I asked Wolfe if they ever feel boxed in by the limited availability of ingredients, he simply responded, “I think it makes it as easy as it is hard. We know what we can use, so there’s no omnivore’s dilemma where you can eat anything you want so you don’t know what to eat.” The chefs see what’s available not as a burden, but an opportunity to break new ground. “[Things like foraging] can give us ingredients other people don’t have access to,” Stringer added—or at the very least, a chance for a group of busy chefs to have a rare quiet moment in the woods.