This story is part of MOLD Magazine: Issue 02, A Seat at the Table. Order your limited edition issue here.

For those of us who loathe family reunions, we know all too well that meals are performances. The aunt’s signature tart that is greeted with frozen smiles and then hidden in napkins for later disposal. The grandiose display of masculinity that goes into tending the barbecue or carving the turkey; the same pre-scripted dialogue about who gets the thigh or the drumstick that is repeated year on year. Not to mention the loaded small-talk and passive aggressive “pass the peas” that keep the darker family secrets beneath the table.

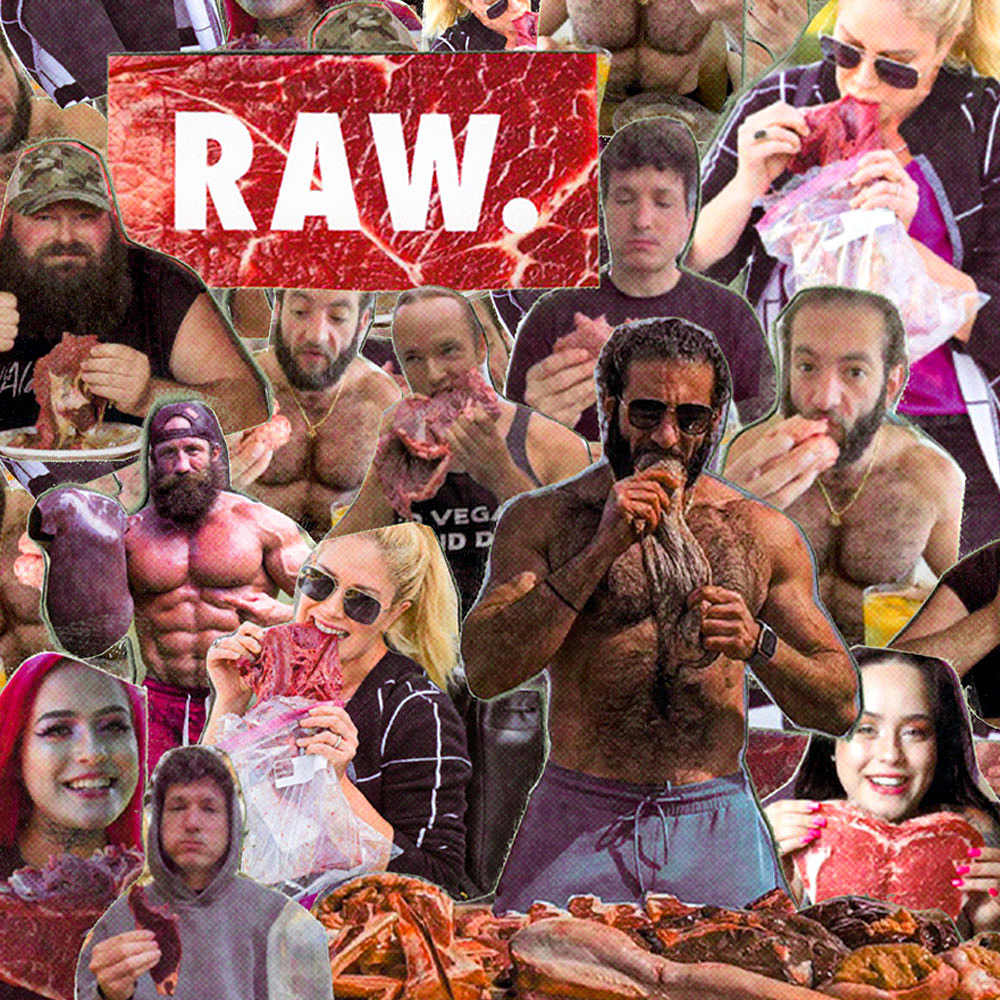

From Acting Things VI Spacial Canvas by Judith Sent.

From Acting Things VI Spacial Canvas by Judith Sent.

Yet it is these very rituals that codify behaviors, embed beliefs and ascribe identity—even for those with more amenable kin. Food and eating offer a gathering point for all manner of groups to come together, providing an opportunity for individuals to act out their relations to each other and society. Food and eating are by nature performative; even eating alone, or shoving down something while rushing between meetings, display who we are. Zooming out from the domestic to the global, the food system is also an enactment of geopolitics.

A table setting for 500 guests to coincide with the harvest moon at Act XXXIX, photo courtesy of Studio Ortega.

A table setting for 500 guests to coincide with the harvest moon at Act XXXIX, photo courtesy of Studio Ortega.

In the fledgling discipline of food design, performance has become a mainstay. Marije Vogelzang’s iconic 2007 Christmas party for Droog draped the table with fabric sheets punched with holes for heads and hands, and one-ingredient plates that forced people to share. Not to mention any one of her interventions that blur the line between performer and audience by intimately engaging participants through techniques like being blindfolded and fed food and stories.

Bompas & Parr’s Organs of London invited guests to feast on animal organs in the workshop of London’s oldest pipe organ builder, Mander Organs. Photography by Jordan Stevens.

Bompas & Parr’s Organs of London invited guests to feast on animal organs in the workshop of London’s oldest pipe organ builder, Mander Organs. Photography by Jordan Stevens.

Relying on more traditional distinctions between performer and audience, Bompas & Parr have expounded food-inspired narratives through immersive banquets that evoke awe and exhilaration. These have ranged from performances of pipe organ music accompanied by eating cooked animal organs to their more recent sausage séance, entailing a banger-making masterclass that turned into a spirit-summoning workshop.

More and more, however, food and performance are being used outside of the realm of food design, by designers with more social concerns.

Bompas & Parr’s Organs of London.

Bompas & Parr’s Organs of London.

“The way we deal with food is as a ritual and gesture in the sense of social cohesion,” says Hannes Bernard of SulSolSal, a collaboration between the South African designer and Brazilian architect Guido Giglio that explores the relationship between the West and the Global South.

The pair have used food and performance to explore topics ranging from the recession to biohacking and neo-survivalism. For instance, “The Banquet” was a food performance inspired by the economic crisis. It sought to create uncertainty by distributing unlabelled bottles of water and vodka, and evoke the need for people to support each other by only offering one-meter-long forks that obliged participants to feed each other.

Bompas & Parr’s Organs of London.

Bompas & Parr’s Organs of London.

“We are interested in economics, politics and cultural exchange,” Bernard goes on. “Food is not a subject, but an even more universal medium than a poster. Everyone has a relationship with food; it is cross-cultural and beyond language, and also a highly manipulative form of communication.”

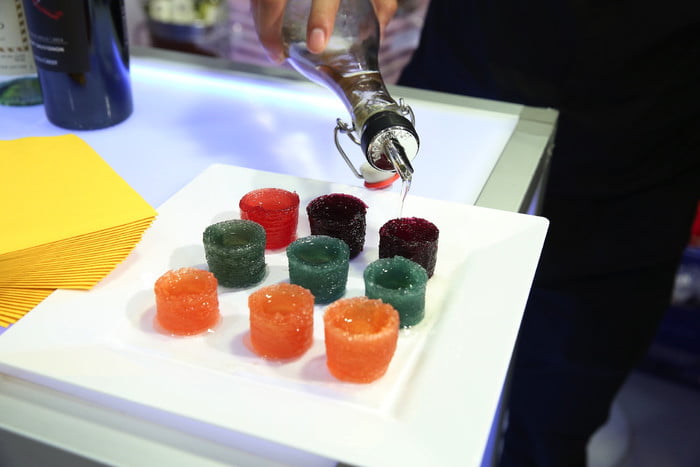

Bompas & Parr’s Sausage Séance combined a sausage-making workshop and feast with a supernatural experience using a meat-based Ouija board designed specially for the occasion.

Bompas & Parr’s Sausage Séance combined a sausage-making workshop and feast with a supernatural experience using a meat-based Ouija board designed specially for the occasion.

Artists Lucy and Jorge Orta, who have pioneered using food and performance to communicate design research since the 1990s, concur. Their ongoing series of 70×7 Meals serve as a means to foster interaction in their participatory social practice. “Performance has also given more visibility as it allowed for a larger audience and public to witness and become involved in the projects, taking contemporary art out of the confines of the museum and into places where it wouldn’t normally be or be seen,” says Lucy Orta.

Bompas & Parr’s Sausage Séance.

Bompas & Parr’s Sausage Séance.

The capacity of performance to bring to life non-physical things, and food’s knack to rally disparate groups around difficult topics, make the combination useful for communicating non-physical designs like systems, coding, interaction, experience, digital, speculative, critical and social design.

Bompas & Parr’s Organs of London.

Bompas & Parr’s Organs of London.

For instance, designer Margriet Craens’ 70% Bar or Restaurant creates an embodied experience of how accustomed we have become to over-consumption by only offering portions that are 30% smaller. The furniture and staff are also roughly 30% smaller or larger, creating a surreal scenography that underscores how problematic standardization is in social design.

Craens has also created a meal-performance centered on IBM’s algorithmic cooking assistant, Chef Watson, and the culturally-bizarre but often surprisingly tasty food pairing it proposes. The idea here is to encourage reflection on the knee-jerk dismissal of artificial intelligence and machine learning.

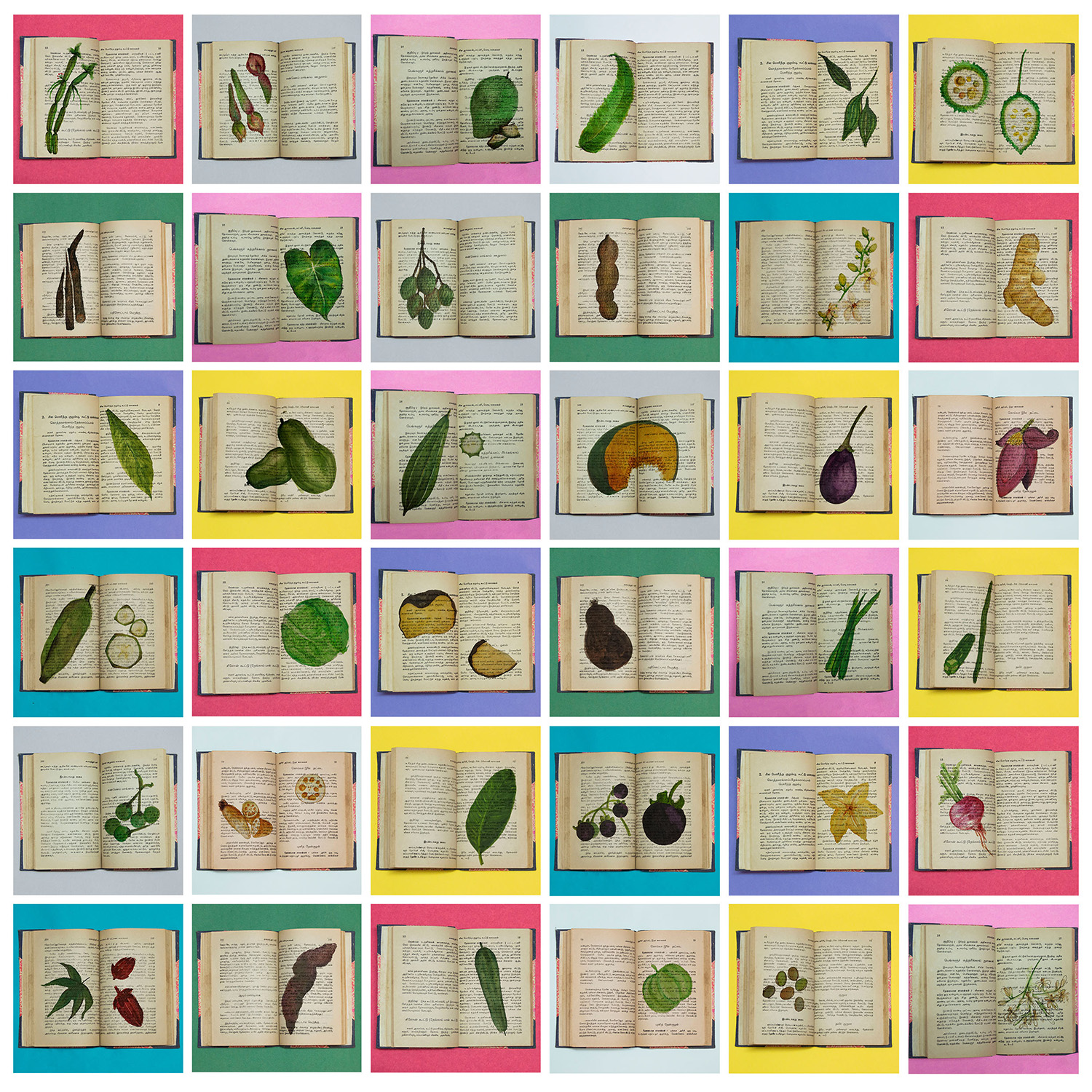

Illustration by Maren Karlson.

Illustration by Maren Karlson.

Even while SulSolSal, the Ortas and Craens would never describe themselves as food designers, insisting that food is a medium for exploring other issues, all of these projects nonetheless highlight invisible social, cultural, political and environmental issues that problematize every bite of food. After all, an imminent global food crisis is not unimaginable with places like Venezuela, Yemen and Nigeria already heading towards famine, while drought continues to cripple much of Africa and the United Kingdom is sweating a Brexit-induced food shortage—not to mention the growing concerns around nuclear war.

If fresh food becomes a luxury, and we are finally forced to resort to Frankenfoods like algae soylent or protein made from carbon, the design question may be less about appearance than the social rituals. How will we endure family holidays without the panacea of satisfying food, or even encourage solidarity and reward success? Food’s role in behavioral psychology and sociology is significant.

Bompas & Parr’s Organs of London.

Bompas & Parr’s Organs of London.

It is this matter of designing rituals that Judith Seng explores in her Acting Things series. Comprising six episodes, Acting Things uses various modes of performance and choreography to explore how the meaning and form of objects is produced through social and material interactions. For instance, the Japanese tea ceremony’s ability to elevate everyday activities to the hallowed serves as inspiration for the sixth episode. Similarly, Seng turns drinking water into a ceremony using only hand gestures.

Bompas & Parr’s Organs of London.

Bompas & Parr’s Organs of London.

It is this ability of design to imbue matter and matters with meaning that will make gathering around a bowl of unfamiliar foods of the future not only tolerable, but also fulfill the social functions that eating serves. In other words, the inadvertent effect of these food performances could not only be a deeper relationship with and reflection on what we put in our mouths but finding new ways to connect and celebrate with each other. Let’s raise the curtain on that.