Pre-order your copy of SEEDS, MOLD Magazine Issue 05 here for a pre-order price of $18USD. Expected ship date is March 22.

The squirreling away of the world’s seeds in “vaults” and “banks” has become increasingly assiduous as our species struggles to halt the rapid decline of earth’s biodiversity. While the necessity for conservation in this sixth extinction is paramount to the preservation of resilient food supplies around the world, the prospect of stowing the future of food behind the thick walls of a “vault” or a “bank”—those institutions that so often cater to only those with privileged access—might sound dubious to those most imminently vulnerable to climate change. After all, if they are not for the access of the billions of us living today, who are they being stored for? Who gets to make a withdrawal?

This is why some people have turned to the “library” as a more egalitarian and accessible interface for sharing biodiverse seeds. The rise of seed libraries in the United States as a means of seed dispersal and cultivation has created an avenue for communities, often in urban centers that would otherwise have little opportunity to share and grow healthy food for themselves. Seed banks, such as the Svalbard Global Seed Vault or England’s Millennium Seed Bank, centralize seed conservation and are designed to keep seeds dormant for long periods of time in highly controlled settings. Alternatively, seed libraries ‘lend’ seeds out each season for anybody to grow, then recollect the next generation of seeds after the harvest. This constant regeneration of seeds ensures diversity and crop resiliency to changing environmental conditions. For millennia before industrialization, seeds thrived alongside nomadic and agrarian humans—the evidence for this ecological history is manifest in the deeply rooted respect and immense value assigned to seeds among indigenous cultures around the world. This pre-industrial relationship was quite advantageous for both humans and plants as seeds must move to adapt, evolve and understand the world they intend to grow in. This is especially true if the climate of that world is quickly changing. Through seed libraries, marginalized communities can cultivate for themselves a source of resilient food.

Just as with literary libraries, the seed library can empower communities with knowledge, and through that knowledge life can grow beneficially for people and plants alike.

Yet seed libraries are only a recent phenomenon in the United States. Since the 1970s seed exchanges like Native Seed SEARCH and Seed Savers Exchange began as banks, protecting rare seeds and cultivating diverse variations of heirloom plants on their own. Many of these larger banks now sell seeds. Seed libraries, however, only started to gain momentum in the last decade. In the early 2000s, groups like the Bay Area Seed Interchange Library (BASIL) Project, which found its home in the Ecology Center in Berkeley, California, and the Richmond Grows Seed Lending Library at the Richmond Public Library in California helped to define the lending model that many seed libraries use today. Since 2010, the number of seed libraries across the United States has gone from a mere handful, mostly in the western part of the country, to hundreds all over. Locations that now host seed libraries include the New York Public Library (2019) and Brooklyn Public Library (2019) in New York, the Boston Public Library (2014), the Seed Library of Los Angeles (2008), the Chicago Botanic Garden Seed Library (2016) and many more.

Access to seed libraries that grow local to these urban areas is what makes all the difference when it comes to resiliency. Having access to a catalog of seed varieties that have been grown in your city or community means that the seeds there will acclimate to the local climate and ecosystem, which is precisely why lending seeds through libraries is great for comprehensive conservation of biodiversity. There are two general approaches to conservation, as defined by the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), the legally-binding convention established by the United Nations in 1992. Seed banks take an ex situ approach to conservation. Ex situ is Latin roughly translating to “out of the situation.” One might also think of a zoo when one thinks of ex situ conservation, as it is defined by the removal of a species from its ecosystem for fear that the habitat of the concerned species may be threatened. The other mode of conservation, which is considered to be the primary mode, is in situ, meaning “the conservation of ecosystems and natural habitats and the maintenance and recovery of viable populations of species in their natural surroundings.” In situ conservation is the preferred form of conservation because, unsurprisingly, if an organism has a habitat, it is more likely to survive. Ex situ conservation efforts are often undermined by the uncertainty of changing ecosystems and the complexity that comes with removing a species from its habitat, which is why it is considered best practice to use ex situ “predominantly for the purpose of complementing in-situ measures.”

As has already been demonstrated by the rapid decline of biodiversity in the United States and globally, savvy and widespread efforts to cultivate diversity is a necessity as the climate changes and ecological crisis catalyzes further. Due to the supremacy of industrial agriculture over the course of the past century, the world has lost 75% of edible plant varieties. In the United States, 93% of food varieties have been lost. Agribusiness continues to control most of the arable land in the United States; in 2019, genetically engineered seed was planted on 92% of US corn acres, 98% of US cotton acres and 94% of US soybean acres. The homogenization and destruction of plant diversity by industrial agriculture continues to destabilize the future of our food supply in the United States and abroad.

When writing about nature in cities in her book The Death and Life of Great American Cities, author and activist Jane Jacobs suggested that “Dull, inert cities, it is true, do contain the seeds of their own destruction and little else. But lively, diverse, intense cities contain the seeds of their own regeneration, with energy enough to carry over for problems and needs outside themselves.” While Jacobs may not have been literal in her use of the word “seeds” here, the notion that regeneration and resilience can arise from the culture of the city is directly applicable to the power of seed libraries. Just as with literary libraries, the seed library can empower communities with knowledge, and through that knowledge life can grow beneficially for people and plants alike.

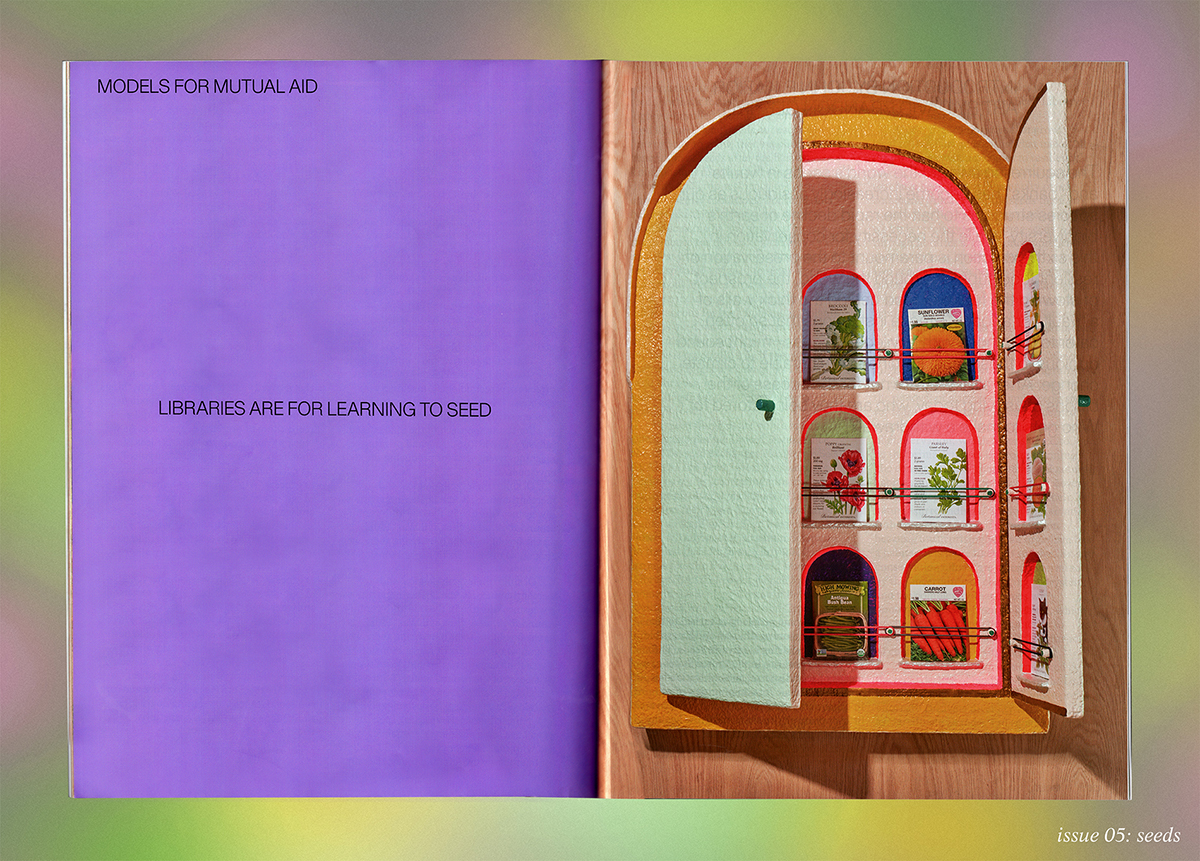

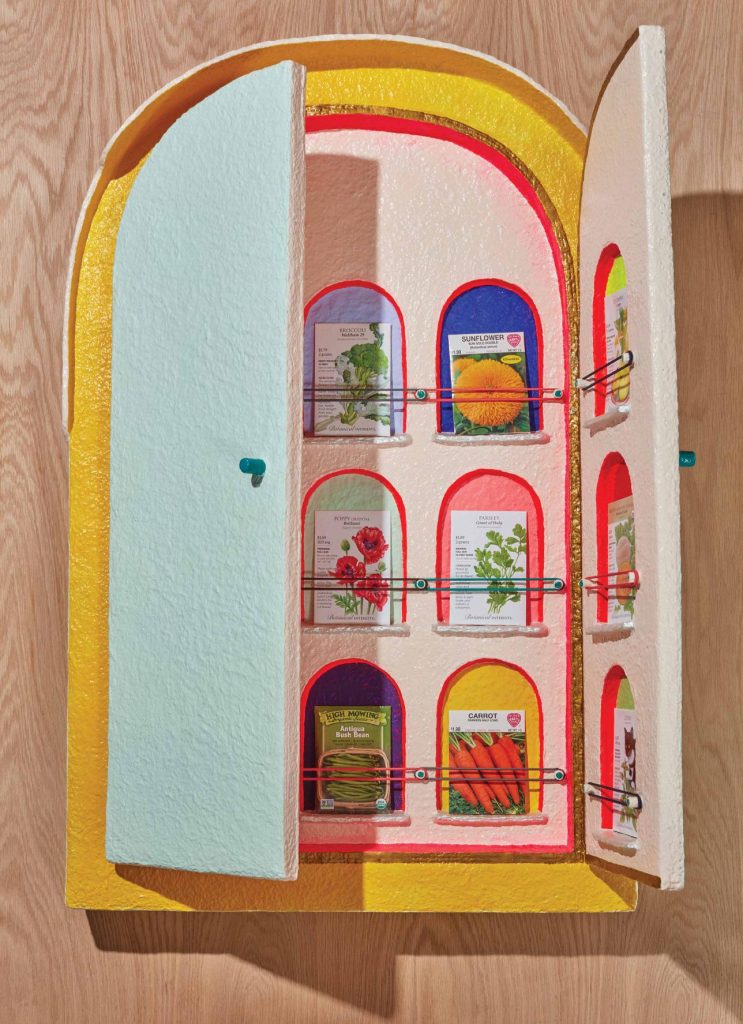

With the COVID-19 outbreak in New York City, we were alarmed by the seismic effect the quarantine had on our already food insecure city. The pandemic amplified systemic inequities in our current food supply chain and the failures of our globalized approach to feeding ourselves and our communities. Inspired by the rise of local mutual aid groups and the Little Free Library movement, MOLD commissioned seed libraries from our favorite New York designers and chefs with the hope that their approach might inspire others to freely share seeds and stories within their communities and beyond.

Read more about the seed library commissions from the artists: