Order your copy of SEEDS, MOLD Magazine Issue 05 here .

In the introduction to my well-worn copy of Vandana Shiva’s 2016 polemic “Who Really Feeds the World?” a single line has served as a North Star for the editorial direction for MOLD. It simply states, “The future of food depends on remembering that the web of life is a food web.” It is a regular reminder that we live an entangled, interconnected, multi-species existence where food should be a right, not a privilege. This sentence also speaks to the power of its author. Shiva writes with a momentum that carries her readers across complex systems, ideas, histories, timescales and geographies with clarity of language, the grace of storytelling and the force of truth.

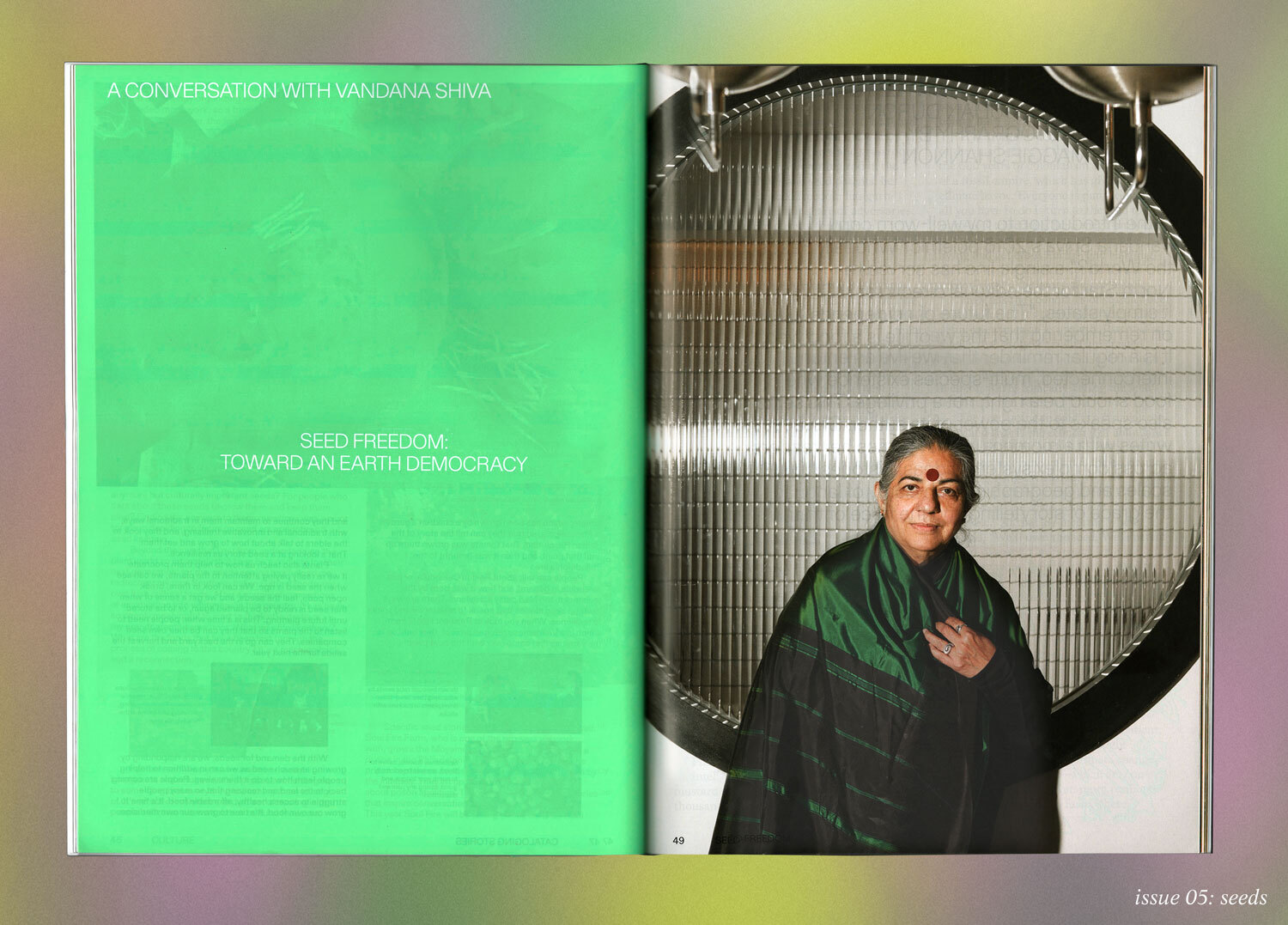

Photography by Maggie Shannon. Artwork by Julian Duron.

For over 40 years, the author, philosopher and activist has championed biodiversity, the integrity of living resources and the voices of women and farmers around the world through her writing, lectures and grassroots organizing efforts. A lightning rod in the fight against GMOs and seed patents, her tireless battle for seed freedom has garnered more than her fair share of adversaries and allies. But despite the criticism, Vandana Shiva remains an unwavering force for freedom.

In preparing for this issue on seeds, there is no better person to unpack what seed intelligence might hold when imagining the scaffolding for our food system. When we met in Los Angeles at the end of January 2020, we could not have anticipated how much our worlds would shift in the next few months. In this moment of global transition and reflection, Shiva’s vision for a “new paradigm for living,” an Earth Democracy that operates through an “economy of abundance,” is a lesson for us all.

LinYee Yuan:

I’ve been thinking a lot about your insight around cultivating living systems and how those systems need two things to thrive: first, a level to establish self organization and, second, a scale where humans can contribute care. These are powerful guardrails for considering our relationship with the earth. When creating a new scaffolding for our food system, what can seed intelligence teach us?

Vandana Shiva:

First, as you said, is recognizing that there is intelligence in the seed. Otherwise, a tiny mustard seed couldn’t grow into a plant with thousands of mustard seeds. And in each of those thousands of seeds, there’s potential for a thousand more, which is how human beings have been nourished by the seed.

If self-organization is the capacity of the intelligence of the seed, it undoes the 600 years of colonialism and 100 years of a fossil empire, which has given us climate havoc. Everyone is panicking, but all you have to do is turn to the seed to learn how to address these mega problems: self organization—becoming part of a living and generous Earth—and learning the economy of abundance rather than subscribing to the economics of scarcity.

How has the economics of scarcity been manufactured? It’s been manufactured by defining extraction as growth. Patents and intellectual property rights are created by pulling out the life of the seed through genetic mining—it’s an extractive industry. In effect, you’re basically saying the seed cannot become seed.

The seed going to seed is a circular economy and that is the economy of abundance—it is the economy of sustainability; it is the economy of renewal; it is the economy of never getting exhausted. We have a prayer, a seed song, when we sow a seed. We say, “Let the seed be exhaustless; let it be forever renewable.” At that ’87 meeting where they said, “We’ll own the seed. We’ll patent the seed. We won’t let farmers have the seed,” they were declaring, let the seed be exhausted so our profits are exhaustless.

Seed intelligence, through it’s being exhaustless, teaches us perenniality. Not perenniality and permanence in staticness, but perenniality and permanence in ever changing, ever adapting evolution. Another part that I have learned from the intelligence of the seed is, of course, resilience. We just saved a few seeds. Then we realized we’ve got to save all seeds. So many of those seeds were climate resilient, flood tolerant, salt tolerant, drought tolerant. In these times of climate change, the seeds we have saved—which are constantly evolving to be even more resilient—have allowed farmers to farm where chemical farming and the Green Revolution has given up.

LY:

Is this economy of renewal, this economy of abundance, the foundation of an Earth Democracy, the new paradigm for living that you advocate?

VS:

It’s at the foundation. This extractive economy has manufactured a lot of illusions. The illusion that capital creates. Capital is just money, money endowed with power. When it’s real money, I know I exchanged money with people. But when you call it capital, suddenly it’s a creative force in the universe, and it’s not. What capital does is extract the creative power of nature, extract the creative power of women. That process of extraction is then called growth and measured by gross domestic product and gross national product—constructions created during the war to take wealth out of society to finance bigger military operations. By a capitalist’s definition, if you consume what you produce, you don’t consume. Since the seed grows out of seed, it doesn’t produce. Women save seeds. That economy of saving is counted as a non-economy. Extraction by the companies and corporations becomes growth.

Another illusion treats corporations as persons, and they have power to take away the freedom of the seed. They have power to take away the freedom of the farmer, and they have power to take away the freedom of the women. They have power to take away the freedom of the bees and the butterflies. That is now defined as freedom of speech. It has become the freedom to annihilate.

Earth Democracy is simple. It’s a recognition that we are part of life. We are all citizens of the earth. Anthropocentrism, the idea that there is a superior species that can rule over other species, is another illusion. That there’s a gender that can rule over other genders, which is capitalist patriarchy, is also an illusion. That’s why ecofeminism undoes that illusion that there is a superior race, which was the basis of colonization and the basis of new hate politics. No, we are all human beings and all earth kin. Our democracy is remembering that we are part of an earth family, that all species have freedom. And it’s the seed that has taught me this.

LY:

In what ways?

VS:

Respecting the freedom of the seed to renew and multiply. Our role is not as master and owner. Our role is as caretaker. That’s why the economy of care is the foundation of living economies of the future. The freedom of the seed and the freedom of the seed keeper are interconnected freedom—they’re not in competition with each other. This interconnected freedom is the foundation of living democracies: freedom for all life on earth and all people, no matter what their color, no matter what their gender, no matter what their race, no matter what their beliefs, and no matter what the class.

Recognizing beauty in diversity is the urgency for our times.

Vandana Shiva

LY:

This Earth Democracy, this economy of care, is a sort of antidote to these practices of violence—the violence of pesticide use, the violence toward the earth—that have been the dominant paradigm for the last hundred years.

VS:

The age of fossil fuels also led to the age of robber barons. It led to the Great Depression. It led to wars. And while there were wars internationally, there were also wars within society, exemplified by Nazi Germany and Hitler’s decision that some human beings weren’t worthy of a right to life, putting them in concentration camps and organizing the corporations of that time into a cartel called IG1 with partners in America. As Germany and other countries were fighting, the corporations were working as one to create chemicals to kill.

All the pesticides of today have ancestries in Zyklon B2 and the poison gases; the chemical fertilizers of today have ancestries in the explosive factories. Rachel Carson said this in Silent Spring, and all my work has shown me again and again that the agrochemical industry is a war industry—it’s a continuation of the war industry, and it is engaged in war against the earth and its species. When we talk about the sixth mass extinction, we need to remember that we have designed these chemicals to exterminate, pushing some human beings and other species to extinction. It is because we’ve defined other species as our enemies, our competitors.

The same worldview is also a big contributor to climate emissions. My book Soil Not Oil tracked how 50% of greenhouse gases come from an oil-based, poison-based, globalized food system. If we want to find answers to the climate catastrophe, the sixth mass extinction, hunger, and the fact that a large amount of chronic diseases today are from the same war industry, then we have to make peace with the seed and, through the seed, make peace with the earth.

- 1. Interessengemeinschaft Farbenindustrie AG (German for “dye industry syndicate corporation’’), commonly known as IG Farben, was a German chemical and pharmaceutical conglomerate. Formed in 1925 from a merger of six chemical companies—BASF, Bayer, Hoechst, Agfa, Chemische Fabrik Griesheim-Elektron, and Chemische Fabrik vorm. (via Wikipedia)

- 2. Zyklon B is a cyanide-based pesticide invented in Germany in the early 1920s. It consisted of hydrogen cyanide (prussic acid) as well as a cautionary eye irritant and one of several adsorbents such as diatomaceous earth. The product is notorious for its use by Nazi Germany during the Holocaust to murder approximately 1.1 million people in gas chambers installed at Auschwitz-Birkenau, Majdanek, and other extermination camps. (via Wikipedia)

LY:

You have said that “eating is an ecological act.” How can people who are not growing their own food participate in building this new economy of abundance through the act of eating?

VS:

When I looked at the Green Revolution, I realized the idea of “high yielding crops” was a maldescription because they were changing the seed of abundance to one of scarcity—in effect they made tall plants become dwarf in order to pump more chemicals. But that meant the food for the earth—for the soil organisms—was gone. The food for the animals was gone. The first step of that scarcity began with the dwarf varieties and then continued with the toxins and the GMOs which have driven the monarch butterfly to extinction. They’ve driven the bees to extinction.

Abundance is where the seed and the food are interconnected again. Instead of eating 10,000 kinds of plants appropriate to place, and creating living economies appropriate to place, we made eating the ultimate act of alienation from the earth. This alienation has reached a climax with friends, and even ecologists, saying, “Oh, we have to stop eating real stuff to save the planet.” That is basically breaking out of the web of life and breaking out of the food system. Food is the connector of the web of life.

When you eat, there is consciousness of how the food was grown. Did it regenerate biodiversity or did it destroy it? Poison-free eating becomes an obligation to protect the earth: Eating as an ecological act, eating as a spiritual act, eating as a recognition of the Dharma of life.

In Eastern cultures we’ve always seen eating as an act that embodies our relationship with the earth—if it is a conscious act. A person who’s not a farmer can still be a co-producer with the farmer through the consciousness of what the farmer is doing and gratitude for farming with care. For that, we’ll have to create justice and solidarity. The same system that has created food scarcity, hunger and ecological crisis has also flipped the situation: now food produced by working with nature, which should be the lowest cost, has become costly. The high cost of production with toxins, chemicals, patented seed, lots of fossil fuel, long distance transport and sacks of aluminium and plastic has become cheap food because it does not internalize the costs. The costs are externalized. A lot of people feel organic is for the rich. No. Farming with nature and eating food from the seed is everyone’s right.

.

It is our duty to create systems where this becomes the way. At Navdanya we began with just the seed. Then the farmers, being seed keepers, said, “We are growing all this wonderful diversity now. Help us because all the markets are only for monocultures.” So we created distribution systems for them. Then local food systems got created, and the farmers engaging in an agriculture based on protecting diversity are actually earning more because they’re not getting into debt spending on chemicals and costly seeds. All they’re doing is paying the debt to the earth rather than to money lenders and corporations.

Economies of abundance can actually spread through society. That is the future work we have to do in creating food systems that work for all beings on earth, for the last person and the last child.

LY:

How do these local food ecologies contribute to a sense of cultural revitalization in those communities?

VS:

The chemicalization of agriculture and the industrialization of farming is basically a separation of humans, including farmers, from the soil, the seed and biodiversity. All indiginous cultures are based on the soil, biodiversity and respect for the seed—the seed celebrations! Conserving, sharing and then building on that conservation of seed creates food economies that work for all. That is Earth Democracy.

If you think your food comes from a lab, there’s no culture there. But if you realize your seed probably has been around for 20 generations, 40 generations, you then start reviving your culture. When you realize the culture of seed saving is in your indigenous culture, then conserving the seed and saving the seed becomes a regeneration of cultural diversity. Biodiversity and cultural diversity cannot be separated. For Mexico it’s the culture of corn. For the cultures in India—we evolved 200,000 rice varieties—it’s the culture of rice. Akshat is the name for rice in India. It has many meanings, but it means the unbroken. It means continuity. It means the perenniality. It means the breath of life.

We have thousands of rice varieties, different colors. And it’s only because we were saving seeds. The farmers come in and say, “I have a green rice,” or “I have a black rice,” or “I have a purple rice.” We are bringing the earth colors of akshat. We have so much aromatic rice. We are bringing the aroma as a function, and then different parts of India cook rice in different ways. This is how the little act of saving seeds becomes a big act of regenerating indigenous diversity at the time of homogenization as the next violence of a pseudo nationalism. Everywhere.

LY:

Yes, hand in hand with globalization. My last question for you is really a call to action to our readership. How do aesthetics and creativity contribute to your vision for an Earth Democracy?

VS:

Recognizing beauty in diversity is the urgency for our times. Why was Hitler so violent? Because he found diversity as something to be exterminated. For him, cleaning up was cleaning out diversity. We need a new aesthetics of diversity. Even in my work on the seed, everything in the colonization of the seeds is about “cleaning up” diversity.

Our farmers have been brilliant in breeding. Basmati, the aromatic rice, is a famous rice from my valley. Basmati is different from other varieties of rice. But in a basmati plant, not every plant is identical. Not every seed is identical. That diversity is treated as a problem and so uniformity has been made. A criteria of intellectual property is that you can bombard the diversity and force uniformity—and I would call it the Hitlerian aesthetic. Things can only be uniform with external control. Wherever there’s a little variation, it’s because that inner urge finds space to coexist and coevolve, and this applies to cultures as much as to our farms, as much as to our plates.

Our souls are hungry for an aesthetic which recognizes beauty in diversity and recognizes that variation is not a problem but an expression of the self-urge of the seed for its freedom.