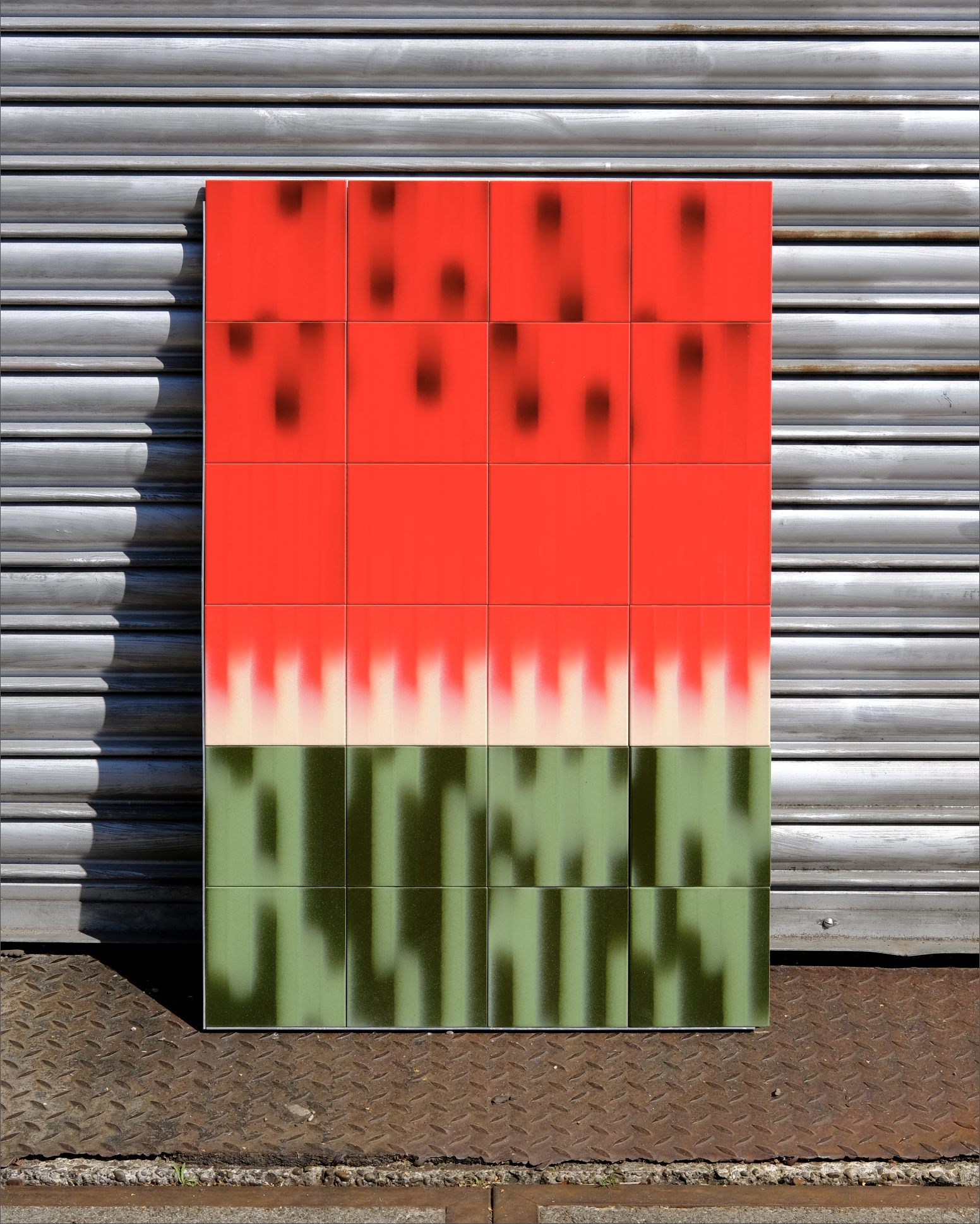

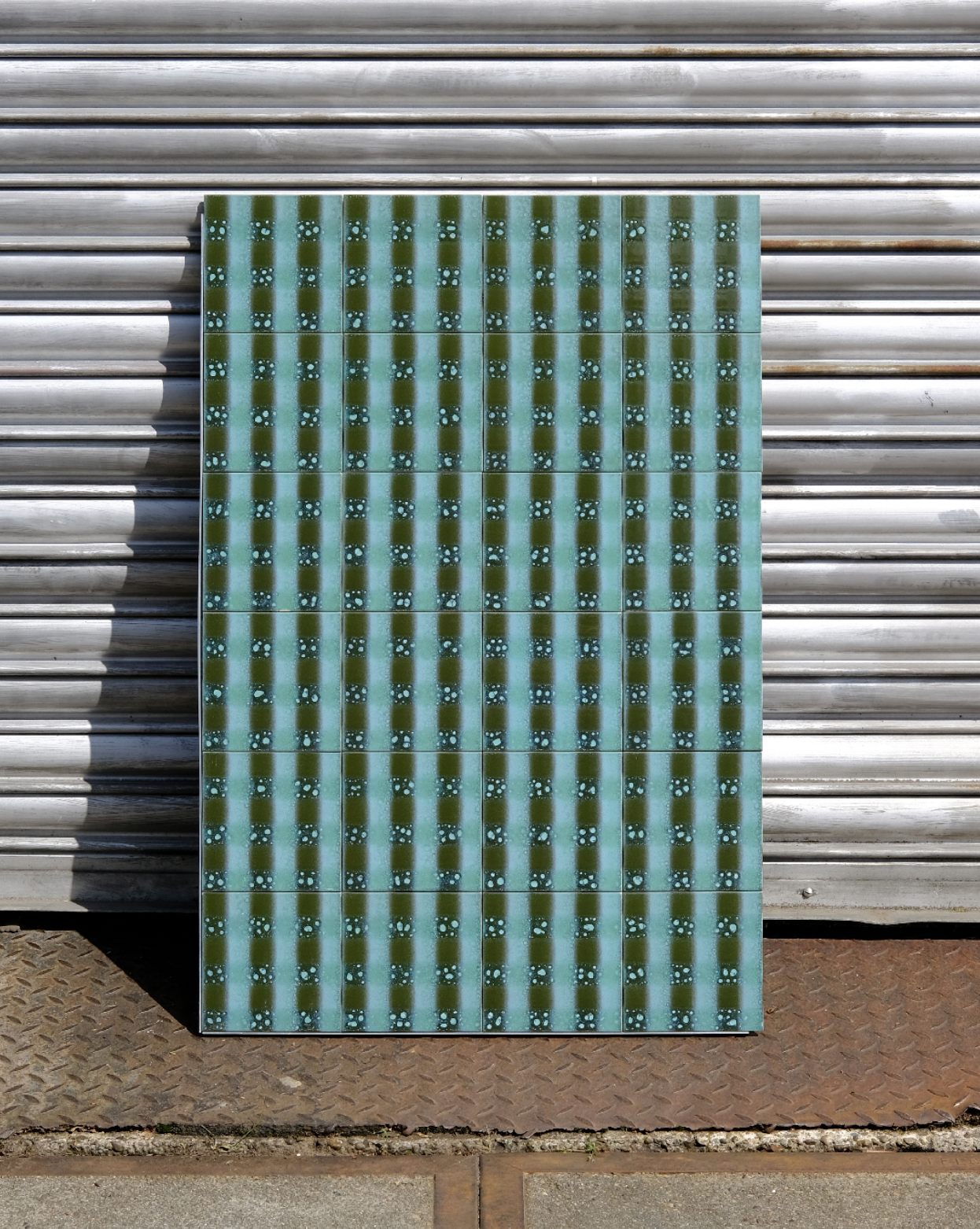

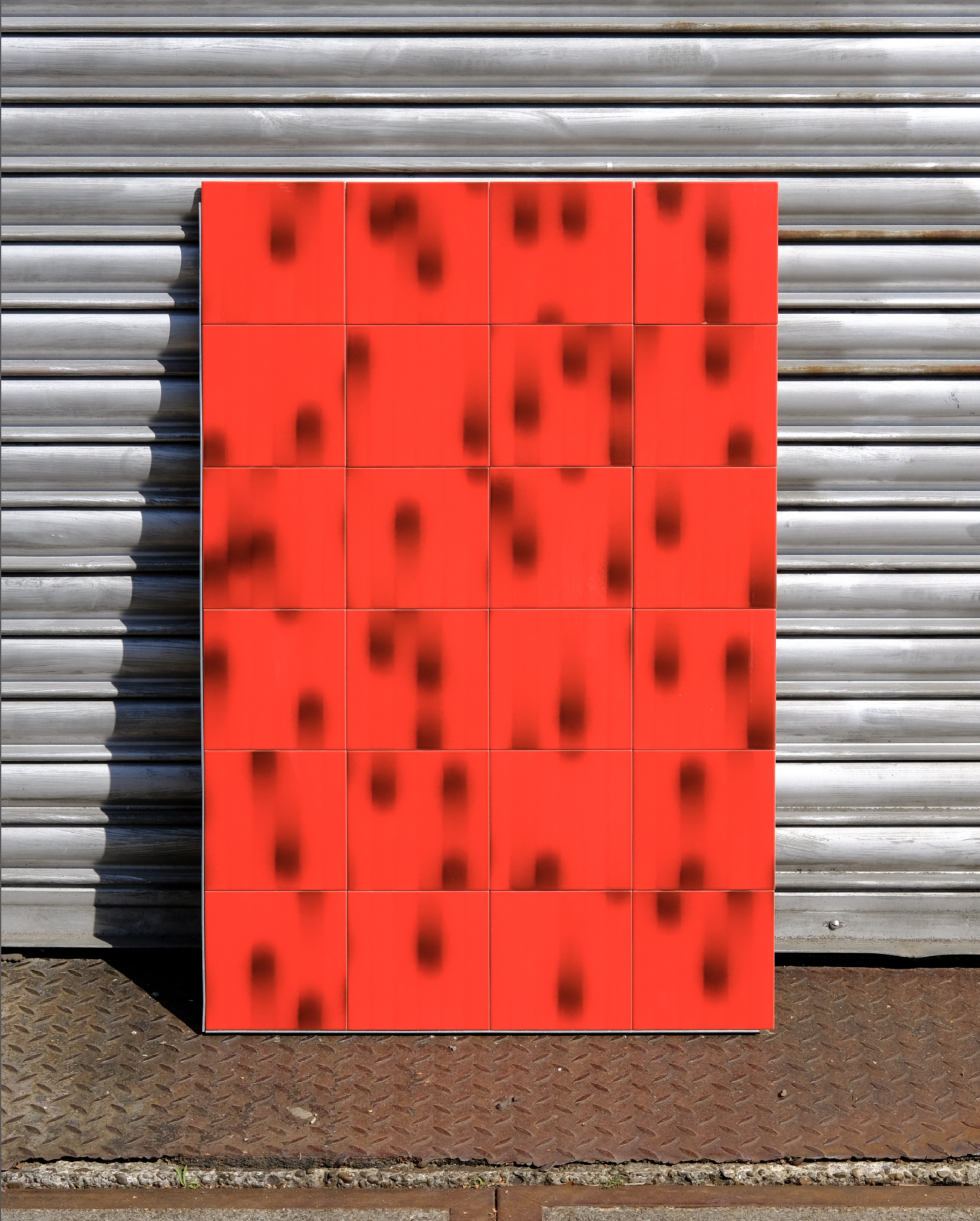

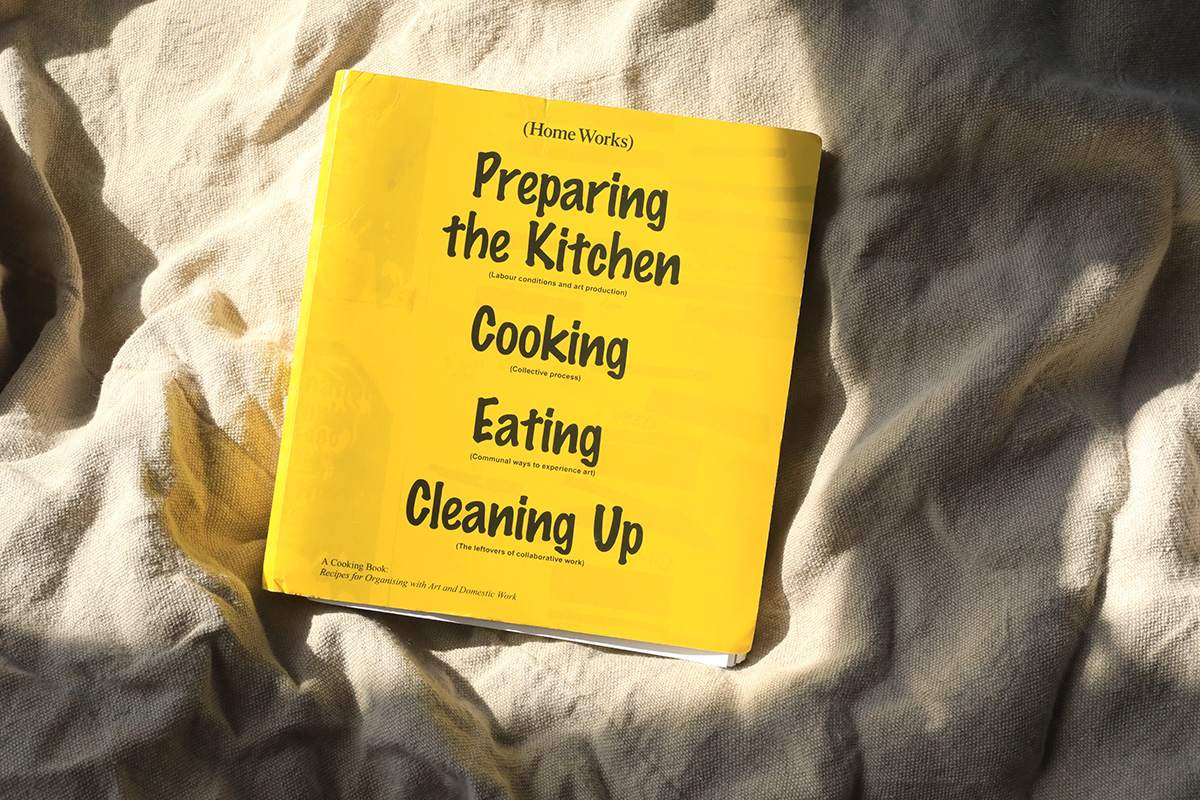

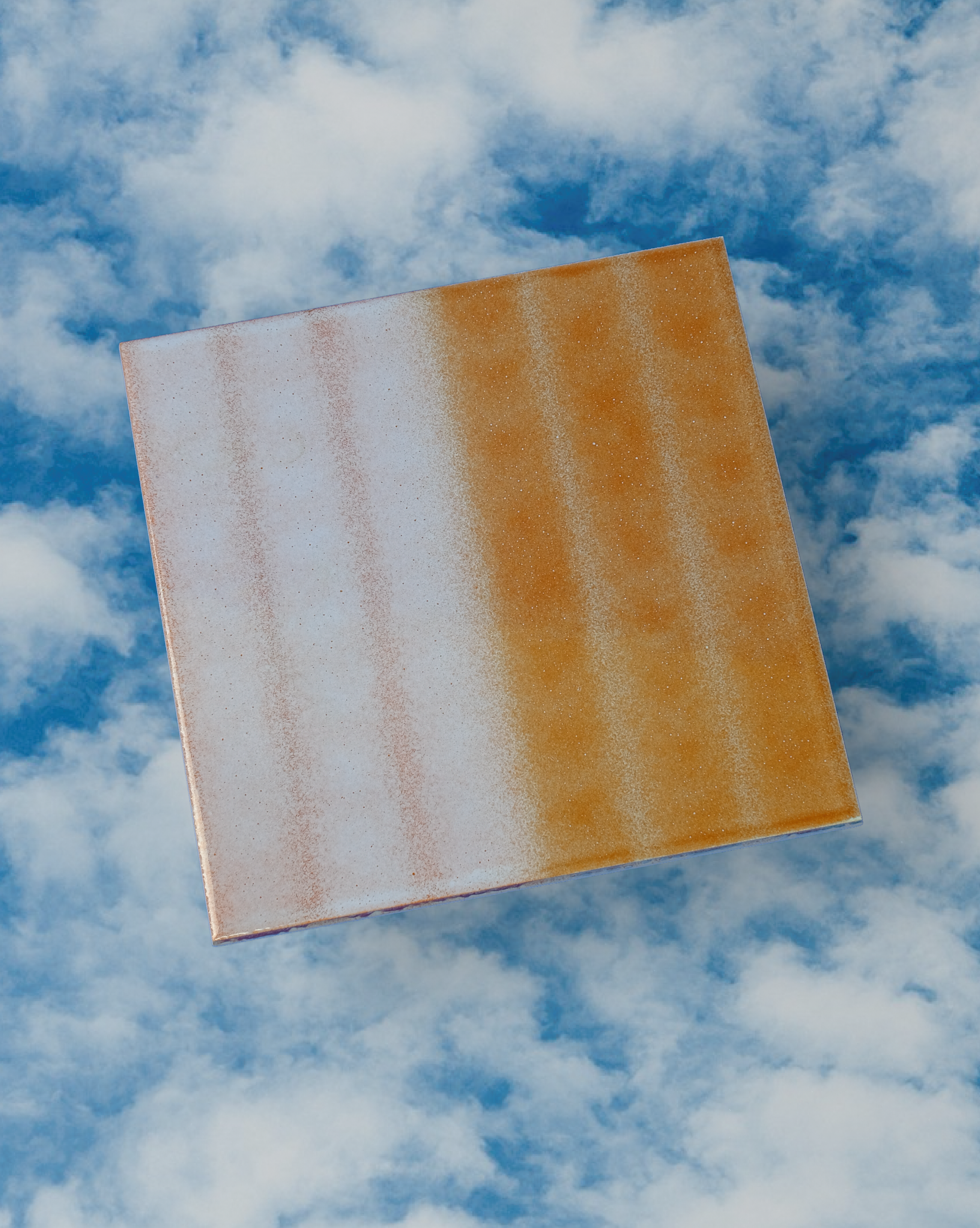

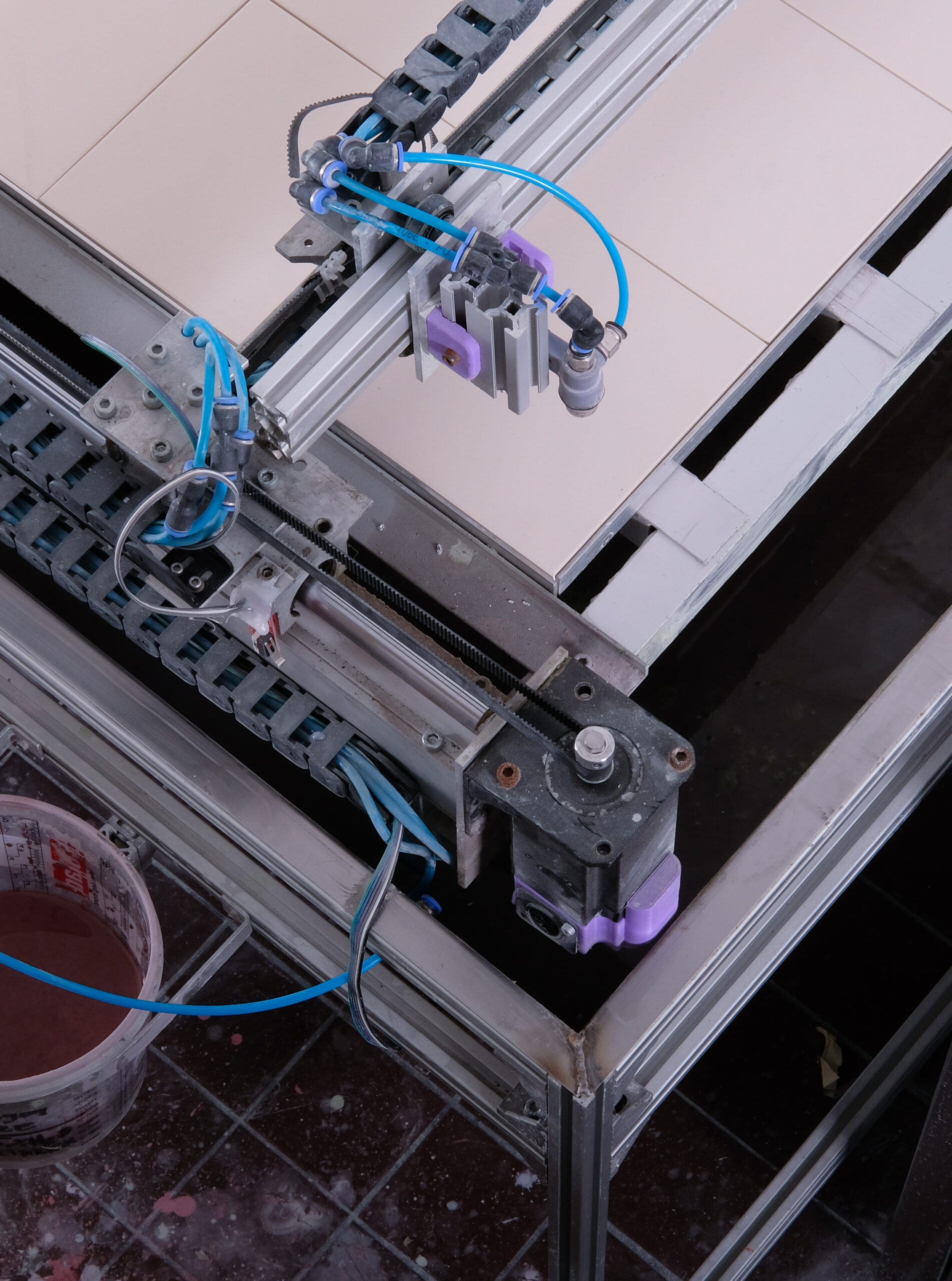

When Gilles de Brock and Jaap Giesen first started their design studio, Studio GDB, they knew nothing about ceramic tile. They did, however, have a vision for what ceramic tile could look like. Drawing from their collective backgrounds in graphic design they set about to create a technology that could bring their vision into reality, eventually building a CNC glaze printer that could translate their playful digital patterns onto bisque tiles. Based in the Netherlands, the studio’s small tile factory draws from a long cultural tradition of artisan ceramic tile factories that once manufactured tiles for all of Europe. However, Studio GDB’s vibrant designs are a far cry from the blue and white designs characteristic of the Delft tile. Instead, the duo’s free-wheeling experimentation— whether it is airbrushing tangerine-hued waves so that they melt into pools of peach or smudging pastel chrome greens into oxidized iron— provide a welcome investigation into color and pattern. In this conversation I speak with Studio GDB about transitioning from graphic design to ceramic tile, building your own tools, and the possibilities in operating from the unknown.

Isabel Ling:

Tell me a little about yourselves, what backgrounds do you bring to Studio GDB?

Gilles de Brock:

I was educated as a graphic designer. Jaap and I actually met while we were both studying graphic design. My personal practice was mostly graphic design posters, but I was also doing a lot of web development for commercial clients. After working in commercial graphic design for a bit, I slowly started working on personal projects like making carpets, silk scarves, and then eventually ceramics, which is what we do now.

Jaap Giesen:

Right, Gilles and I met in school almost 16 years ago, and I was studying graphic design then, but I dropped out in my third year but was able to land a nice job with a studio that introduced me to the world of vintage furniture design. At that studio I just really fell in love with the world of vintage furniture, and working with a gallery of vintage high end furniture, I also became really fascinated with interior design. Despite not finishing school together, Gilles stayed connected as best friends, and we started to find ways to collaborate across both of our fields.

IL:

Drawing from both of your pretty wide-ranging backgrounds how did you land on ceramic tiles?

GB:

I had a residency in Narita, which is the birthplace of porcelain, where I started making ceramic tiles. They were really garbage. But Jaap came to visit because we are best friends and just wanted to hang out in Japan together. But then he saw the tiles and was like “Yes, this is it, let’s do this.” So we decided then and there that we would start a tile company. Of course, it took some time to figure out how to put together a tile factory, but we’ve been working full time for the past half year.

JG:

We both had no experience with anything ceramic related. My fascination with tiles really began when I was visiting Gilles in London, where they have these amazing subway stations with glazed bricks. They were a very pretty dark green, but it really sparked something when I realized how much more could be done with [the medium in terms of] color and patterns. So when Gilles started building the printer, we really placed an emphasis on building something that would let us go crazy with pattern. Also during this period, Gilles and I lived around the corner, so it was easy for me to drop by. So on Fridays, when we would usually be hanging out and having a beer anyways after work , we would also be working on tiles.

IL:

Did you have a design vision that influenced or inspired your decision to make the machine and how you built it?

GB:

It was actually completely the other way around because the machine influenced how we designed the tiles. My design style is actually completely different from what we produce in tiles right now, as most of what we do now is very pattern-centered. I really think we both grew as designers in the development of this machine because of how long it took, and we got to spend a lot of time interacting with the machine in terms of what it can and can not do. And of course, you start discarding the ideas you cannot do, and shifting to optimize the work you can do, and explore possibilities within these limitations.

A lot of the design [process] happened within the realm of the machine itself, because we developed the machine and the software ourselves. It’s in how the code translates the images that we first translate into instructions for the machine. There’s also design influences and decisions in optimizing the machine to make it faster, or performing an aesthetic experiment with this tool. Essentially it’s always this relationship that we have with this monster that we built, which in some ways feels like we have to tame and have a relationship with in order to create things that we like.

IL:

Right, could you give a brief overview of how the machine works as a CNC Glaze Printer?

GB:

Yeah. So every tile design starts with a PNG that we’ve made in Photoshop, one tile that is six by six pixels, a super tiny design file. Then, in order for that image to work for the machine, we need to translate it into motions that the spraying nozzle can follow. So there’s a piece of code that we use in our program that looks at an image, then figures out a way that it can effectively print it and how to print it fast. The code then creates a G code file, which is a commonly used file type for CNC machines, and that file goes to the printer that we built which is essentially a CNC machine with a spraying nozzle. We add the glaze to the machine and the bisque tile and it adds the glaze to the top of the tiles.

IL:

You’ve said that you embraced designing within the range of the machine’s functionality and limitations, but what has your process looked like in experimenting with ceramic tiles from scratch, especially in collaboration with one another’s background?

GB:

With our tiles, the glaze experimentation in itself has been a whole world in itself. We came to it essentially knowing nothing about it. But we begin with industrial glazes because they are very stable and then add pigments and oxides and see how it goes. It’s very different from our backgrounds in graphic design because in that field you can see essentially what you do before or while you’re doing it. With ceramics you have to wait a long time and even after all these years of working with this machine we still really cannot predict if an outcome is going to be what we want it to be. It really is just constant experimentation that allows us to make these designs.

JG:

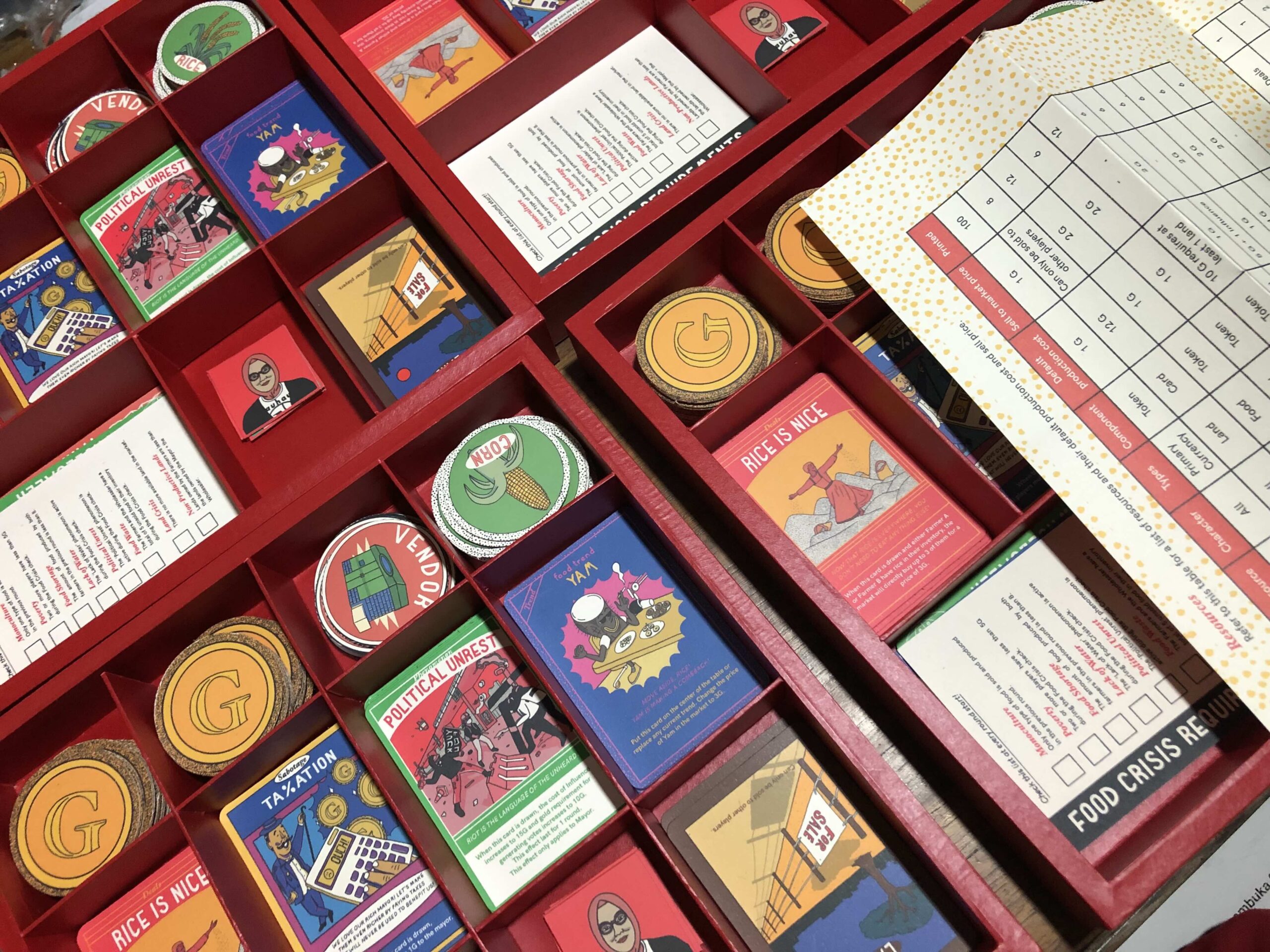

And now our clients play a role too in our collaborations. They order tests that sometimes we would never consider, sometimes because we think that they might be garbage [laughs], but they turn out to be really beautiful and then of course we are happy to take the credits then [laughs].

One of my favorite designs we’ve actually created was for a project we did with Uchronia, a design studio that came to us with an idea that was a variation on two different tiles designs we had previously made. We would have not done it ourselves, but they pushed us to approach the design, and I’ve really enjoyed that sort of negotiation between us and the clients that comes with making tiles that are to be used in spaces like stores, cafes, hotels and kitchens.

IL:

With your machine you are able to create these really beautiful gradients and patterns. How would you describe the design language and direction Studio GDB is taking?

GB:

At the moment, when we think about the experiments that we still want to do, they’re not necessarily driven by aesthetics. So much of what we do is first of all trying to make it affordable, and make it so it’s something that we can do on a larger scale and then we work with the design possibilities that we have. So back when I was doing graphic design, I really liked silk screen printing. And I liked screen printing because it made the blank canvas a little bit less scary because it gave you a lot of limitations and a lot of rules that you had to adapt to in order to make it work. That’s what I really like about these machines as well, because the machines now create these rules for us that we have to stick within. Now when we think of future products we want to develop, we think of, for example, new nozzles that we want to use because they’re more efficient or we think of another printing method altogether or how the tiles enter the machine, those sort of practical things. And then the design aspect comes afterwards because there are always a lot of possibilities within design. And I think we can always make a design work within the limitations that we set for ourselves. So it’s, it’s odd because I don’t wanna say that we don’t think design is important, but the other parts do come first.

IL:

I noticed that on your Instagram when you display the tiles they actually look a bit like a framed poster, was that on purpose or in reference to your silkscreen practice?

JG:

Actually that’s just how we print them, the tiles come in four by six plates because that’s the size of the machine and it’s easy to handle, not too large or small, and allows us to keep them as a base. We started using them as our method of display because we have those plates lying around.

IL:

You guys are based in the Netherlands, which has a really rich history with ceramic tiles. Did you draw from that at all when building your practice?

GB:

Right, there used to be a lot of smaller tile factories in the Netherlands and they all had their own specialty and they made specific tiles. And I think you saw tile factories like this all over Europe and probably all over the world. Of course, those are all gone now and it’s a few giant big factories. When we think of our little tile factory, we would really like to see ourselves as one of these sort of older, traditional craft factories.

As for the ceramic aspect, we went to a European Work Center in the Netherlands that’s actually close to where we both were born and gained a lot of knowledge from that. Because we were essentially starting from zero when we decided to make ceramics. At fir you’re like how hard can it be? But then quickly it becomes clear that that is not the case, you have all these recipes with crazy ingredients or like instructions that ask you to dig a hole to create new ingredients all while calling it some crazy Harry Potter name, and that’s how they used to do it. The work center made it less scary, so that we could look at what the greater tile industry was already doing and had already streamlined, and work from there. Now that we know those things, we have been able to experiment, to really butcher our tiles. And a lot of what we make has come with trying things out that ceramic artists tell you to never do, so in that way, what we are doing is quite new.