In colleges and universities across the globe, design is taught as a discipline existing at a crossroads between art, engineering and history. Depending on your educational background, skill set and personal experiences as a designer, your relationship with these various pathways shapes the work you create. Some approach design as a fine art while others envision it as a meticulous process of engineering—designers fall across and outside the spectrum. The historical aspect and cultural presence of design is ever present and lucid. Political ideologies and cultural histories shape the way designers cultivate artifacts. Oftentimes, fields of design are unable or unwilling to face the cultural impact of their work. Other times, this historical presence is aestheticized, romanticized and glamorized to appeal to current mainstream sentiments. However, on rare occasions, design becomes a tool to understand, express and learn from the cultural history it embodies. Through thoughtful object design and breathtaking visual essays, studio dach&zephir wield this tool remarkably.

Images courtesy of dach&zephir.

Dmitri and Florian, both graduates of the National School of Decorative Arts in Paris, are the two halves of dach&zephir, a design practice they founded in 2016. Inspired by the literature of Martinician poet and theorist Edouard Glissant, the pair work with design as a poetic lense to understand the material reality of stories and histories. In Sun of Consciousness, Glissant exclaims, “I conjecture that perhaps there will no longer be culture without all cultures, no civilization that is the metropolis of others, no poet who can ignore the movement of History…” These words embody Glissant’s theory on culture being a transitory experience through which reality is understood and into which it is expressed. dach&zephir build the framework for their design work on Glissant’s powerful theory. Their work, recognized as exceptional by the likes of the Carpenters Workshop Gallery in London and the 35th Hyères Fashion Festival, centers around designing thoughtful objects which embody the cultural specificities of territories across the Global South, particularly the Caribbean.

Exhibited globally from the Grand Palais in France to the Shenzhen Museum of Contemporary Art in China, dach&zephir spoke to MOLD about their process driven work. They shed light on the material presence of their objects and the knowledge which is unearthed through the intimate process of understanding and expressing a regional design method. Working in both the organic and inorganic materials, dach&zephir seek to expand perspectives through powerful sensory creation.

Hiba Zubairi:

The wearable pieces you make respond to the human body in such an intriguing way. Where does material become central to your design process? What connections do you find between organic and inorganic material?

dach&zephir:

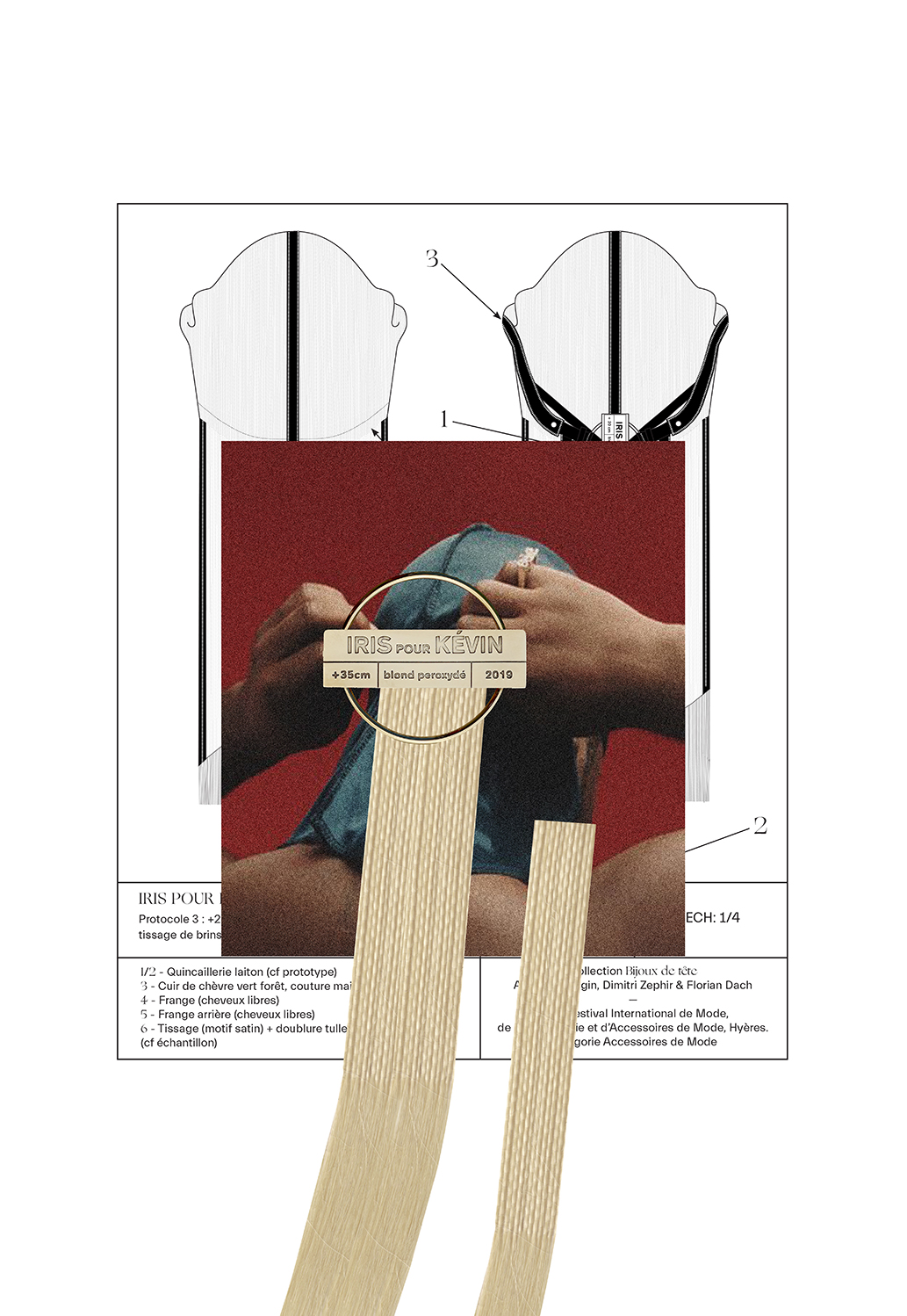

The wearable pieces – titled Bijoux de tête collection – are the result of a collaboration with the textile researcher and designer Antonin Mongin, with whom we won the special prize at the 35th Hyères Fashion Festival. As with many of our projects, the question of skill and it’s revaluation through a design project is inevitably linked to a specific material. It defines a perimeter of possibility that we strive to build with accuracy, which allows the project to be in a form of continuity.

dach&zephir:

Mongin’s research proposes to revive a craft practice that disappeared at the beginning of the 20th century: the “art of working with hair”. Practiced since the 18th century in the West, it consisted of the donation of a loved one’s cut hair to a hair artist so that he could shape this intimate fiber to create tailor-made sentimental jewelry.

The collection presented at the Hyères Festival is made up of seven headpieces, featuring seven life stories told or observed: each accessory is a tailor-made piece – to be worn or given as a gift – designed from a hair donation entrusted to us by identified individuals (a specific individual, a couple of lovers, friends or family members).

Starting with the cut hair as raw material, it is both a technical and prospective research that is proposed, reflecting on the potentialities of this updated tradition. To another extent, it is also a new definition of jewelry and luxury that is told through this collection.

dach&zephir:

Because of its everlasting link to the body and therefore to humans, hair is a material with a high identity and memory value. As designers our job is to deal with the specificity of materials – organic or inorganic ones – and create the great context to explore them.

Hiba Zubairi:

What do you hope to learn from regionally specific design? How does the design history of a site inform your process?

dach&zephir:

We believe in a balance between beauty and meaning in our creations. Our work is a celebration of life as the Italian designer Ettore Sottsass proposed when people asked him to define design. Design is not a discipline isolated from the world and its realities. We embrace with great pleasure the different fields of design, always with the aim of enriching and enhancing the objects we design.

We think it’s probably a better way to engage with a broader audience than producing something that will speak and appeal only to the initiates.

Hiba Zubairi:

The objects you make can be classified as luxury objects and wearables but the communities you involve and engage with in your creative process are much less exclusive. What is the bridge you hope to create between the two and how does luxury fit into indigenous tradition?

dach&zephir:

The nuance is important: “they can be classified as luxury”, but they are not really. If the big series has undoubtedly helped to rebalance living standards, it has also shifted values. We no longer buy, but we consume – with the perverse effects that this can have – and then we throw away. There is a whole education of consumption (of objects) to be redone, as is already the case with food. Buying a tomato in season, for example, means tasting a flavor, a fruit that has matured. For example by buying the tiban that we designed for the Guadeloupean brand TIBAN, you are participating in the Caribbean economy by paying local craftsmen and local wood. You are buying a timeless product, the bearer of a tradition, of a heritage that has long been neglected by the mainstream brands. A better question could be “why objects that are the right price and propose to extend knowledge are seen as luxury?”. This approach should be at the very essence of the objects.

dach&zephir:

And for the Bijoux de tête collection, the headwear typologies are by definition unique and made using a time consuming unique craft which make them fall into the category of luxury product. They are also voluntarily borrowed from an urban and popular culture, this displacement of use was a way to highlight forms (and histories) that have always been de-emphasized. The do-rag, for example, is often associated with the ghetto, with Afro culture, even before being looked at as an object of use (and of style). In the same way, the frizzy hair used for the bucket hat Mirella proposes to open up this ancestral know-how to a hair that has long been misperceived in history.

dach&zephir:

These displacements are ways of shaking up the way people look at things, and their preconceptions.

Hiba Zubairi:

What is the inspiration and process of creating the Creole Library?

dach&zephir:

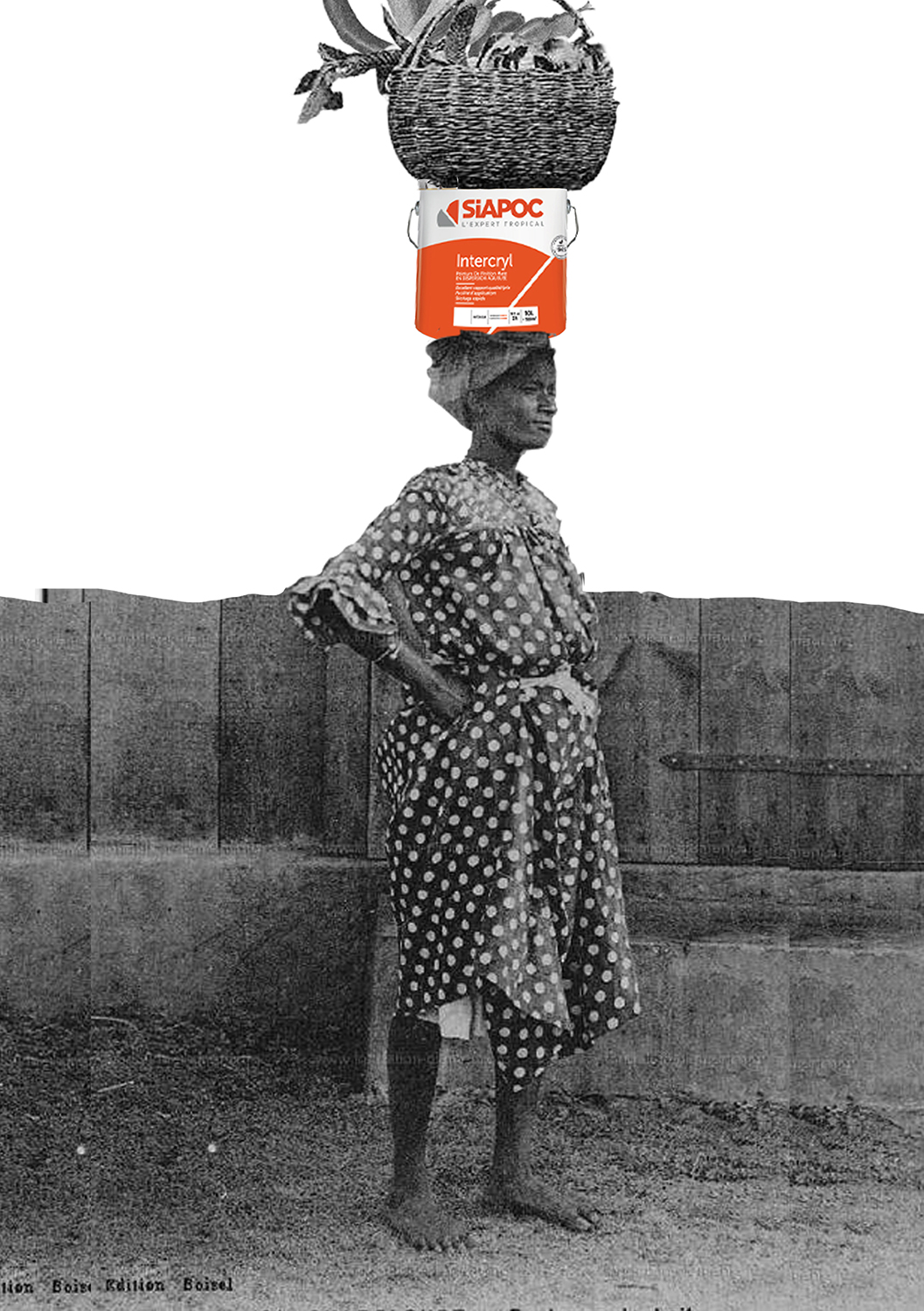

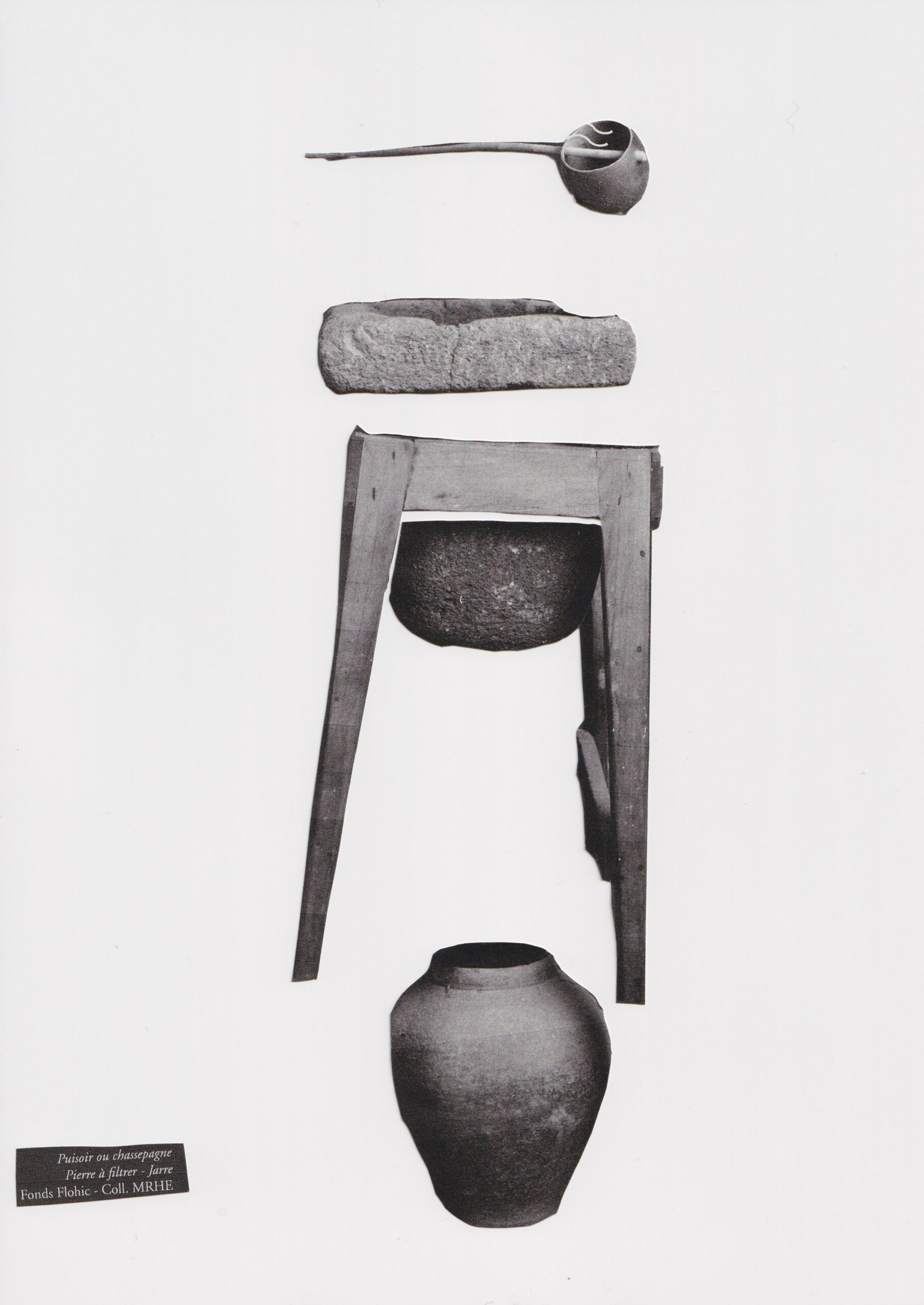

The Creole Library is the continuation of the design field research we have been developing in the Caribbean since 2015. During several trips to Guadeloupe and Martinique, we collected materials/things that echo to a creole imaginary beyond the objects we design. Some of them were offered as gifts by locals and craftsmen we encountered. They are forms, materials, colors, gestures, assemblages that we look at for what they are. In a way, it is a kind of open grammar from which we can draw.

dach&zephir:

When we were invited to the group show “Slanted/Enchanted” curated by Jamie Wolfond for the Erin Stump Projects, we naturally turned to this library, which over time has grown significantly. The items chosen echo creative practices that exist in the Caribbean but are not considered as “academic” know-how’s. These are forms of creation and reinvention that manifest themselves in a very spontaneous way and that we found interesting to witness.

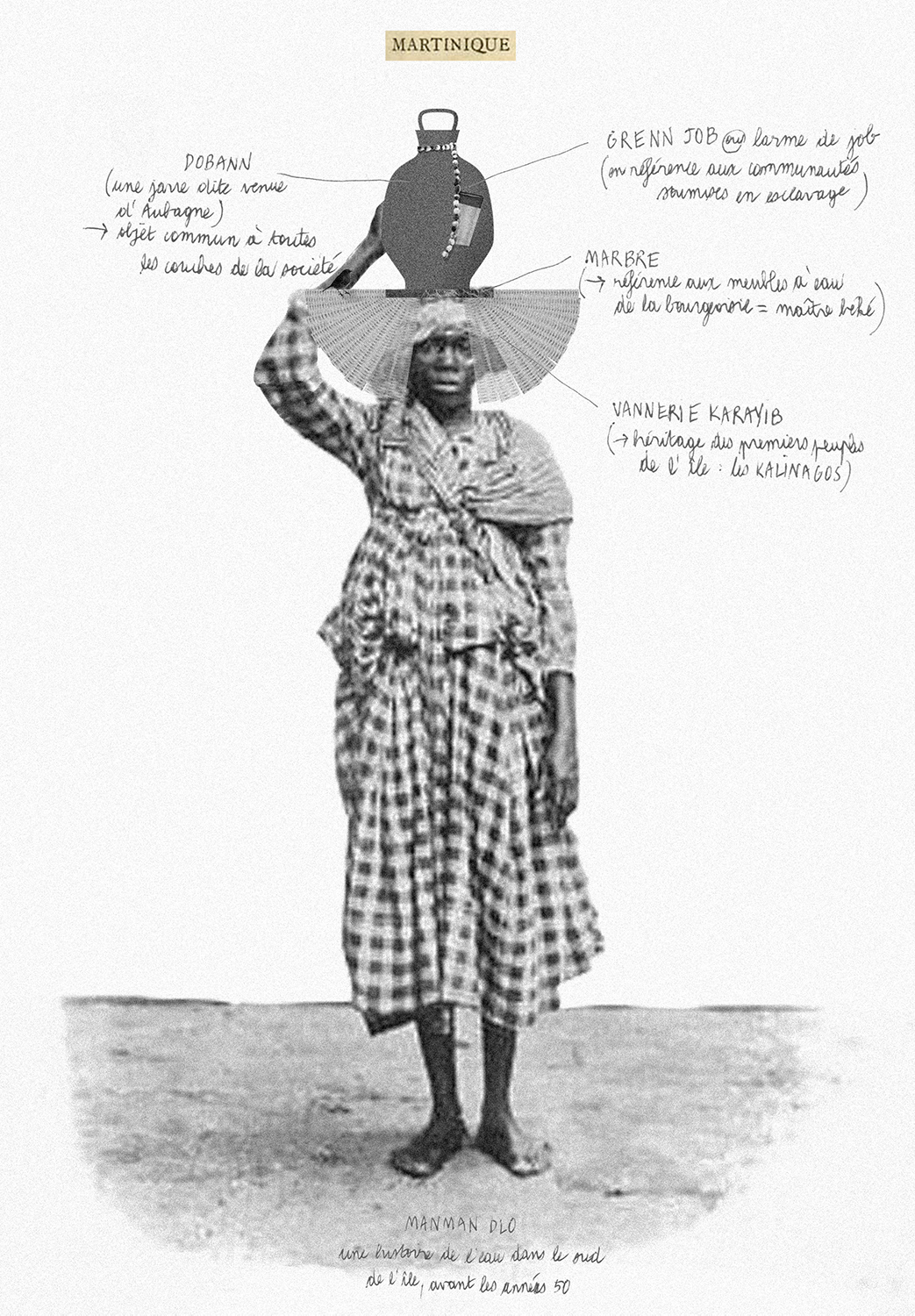

For example, the green a maléré (Coix lacryma-jobi, in Latin; Job’s-tears, in English) is a tall, perennial grass that grows in wet ditches or flooded areas. It is recognizable by its leaves – which are similar to those of sugarcane – and it forms a seed from which greenish flowers emerge in spikes. If the places where it grows are generally unattractive, its seed attracts significant curiosity. Oval in shape, its color varies from greenish to bluish gray and brown. When the styles of the flower are removed, what is left is a hard and shimmering pearl, whose colorful – almost iridescent – effects render it similar to the mother-of-pearl produced by oysters. Naturally pierced on both sides, this seed-pearl suggests decorative and contemplative uses.

dach&zephir:

From the 1720s, the colonial authority had, in fact, put in place sumptuary laws which defined a “stylistic” code for slaves. These could not wear certain fabrics – notably lace and silk – and gold jewelry, for instance, as these materials were social markers of colonial society. As symbols of wealth and power, they were the prerogative of the ruling class – the white masters.

The two undervalued exotic woods (coconut palm and snake wood) are two types of singular woods you can find in the Caribbean. But these are rare woods, which are difficult to work (in large series) because of their high density which can damage conventional machines. Their pattern is also very singular, which paradoxically makes you want to project them into objects. They really are jewels…!

dach&zephir:

Behind this library, there is a multitude of images and stories that are replayed in the creation of these pieces that are voluntarily between the functional and the decorative object. They are forms of DIY that also become creative parentheses within the studio.

Hiba Zubairi:

Are there other projects you have coming up? How is the changing landscape of technology, design and politics informing your future designs?

dach&zephir:

As for many people, the pandemic of the last two years has considerably changed our planning. Nevertheless, we hope to be able to present two collaborations that we started in 2019: the first one with a French industrialist for the production of an “object” in very large series and a collaboration with a French-Japanese editor for whom we designed a collection of objects around the know-how of Ranma – a type of wood carving of traditional Japanese houses.

dach&zephir:

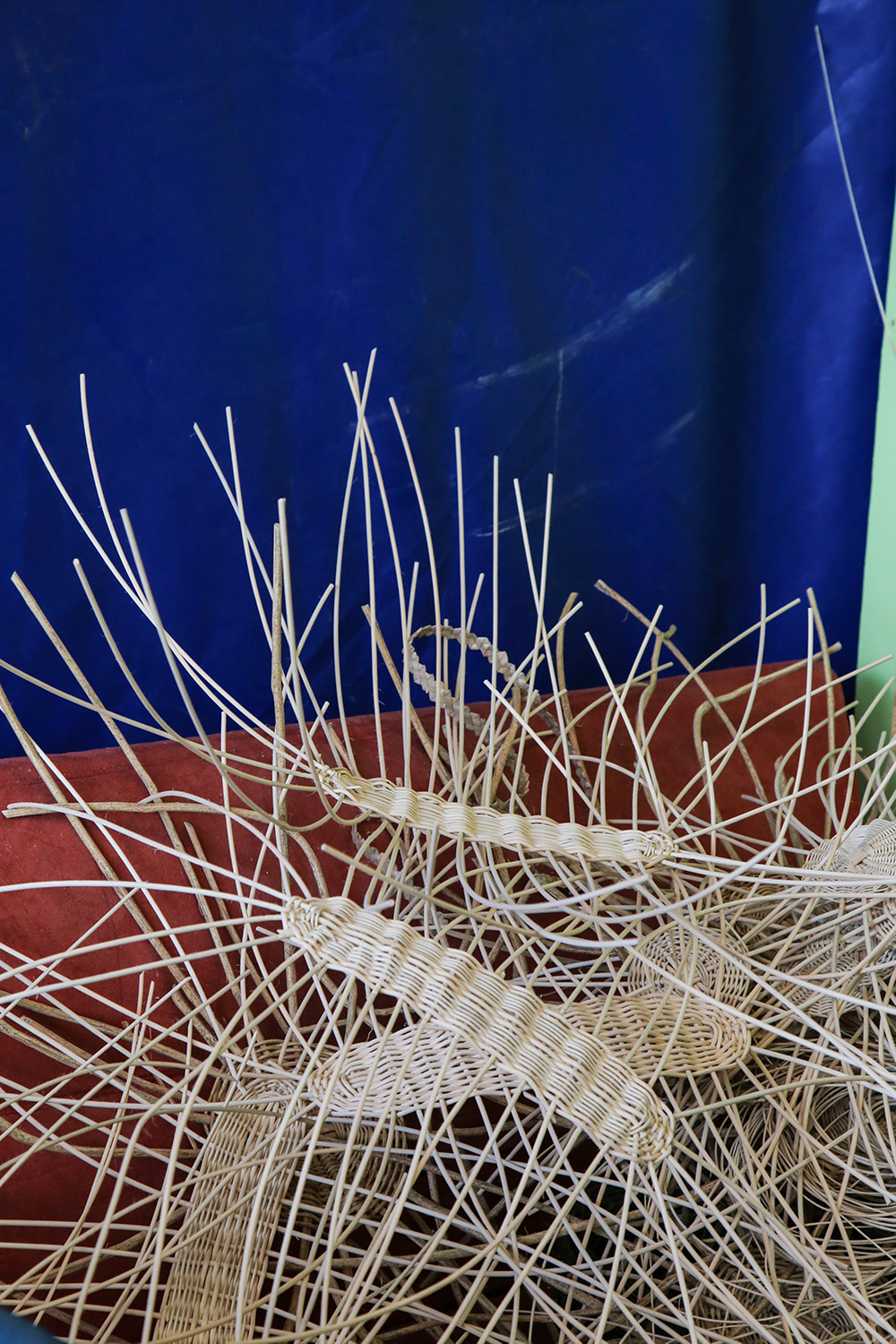

We are currently working on a collection of basketry objects between the West Indies and metropolitan France with the support of the Enowe-Artagon production fund and the FoRTE program

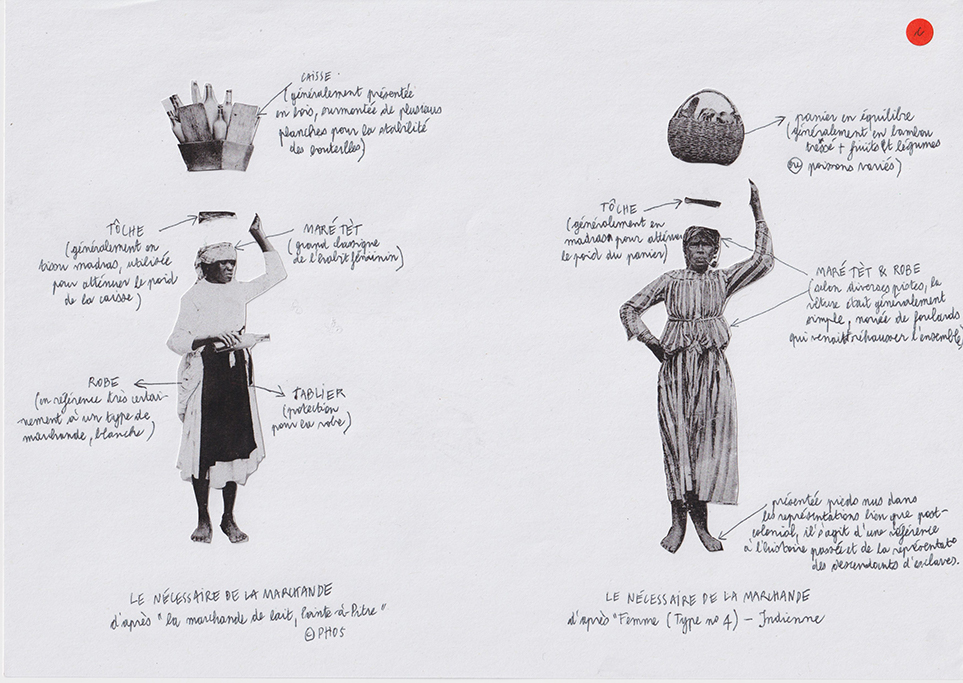

The project titled Panié Machann is a research project around the idea of creolization through design, exploring the French art of basketry and its manifestations in the West Indies and in metropolitan France. It is a continuation of the Eloj Kreyol project, a reflection initiated in 2015 on the forgotten histories of the French West Indies.

dach&zephir:

We are also laureates of the AMI Mondes Nouveaux, a grant of the Culture Ministry of France that allows us to develop a dedicated platform for the research of Eloj Kreyol. We are thinking of a collection of domestic objects that celebrates the idea of a Caribbean’s ways of life and proposes unconventional matches between crafts, manufactures and industries.

dach&zephir:

In a near future, we will present a new installation project commissioned by Studio Dots for their exhibition Histoires de serres realized in the framework of the loop – down the hills across the land program curated by Anna Loporcaro and produced by the commune of Sanem (Luxembourg) and coordinated by Severine Zimmer for ESCH – European Capital of Culture. We will share more about it very soon!