This story is part of MOLD Magazine: Issue 01, Designing for the Human Microbiome.

Grant Harrington’s cultured golden-yellow butter, served at myriad Michelin-starred restaurants in the UK, is some of butteriest around. Dr. Johnny Drain, co-editor of MOLD Magazine, caught up with Harrington about the wonders of butter and his creative process.

* * *

MOLD: Do you have strong memories of butter from your childhood?

Grant Harrington: Not really! I grew up in the time when butter was deemed incredibly unhealthy for the consumer; but as a real treat, sometimes, we’d have Kerrygold on ham sandwiches at my Grandma’s. So you can imagine my surprise working in my first Michelin-starred restaurant at 19 where butter was literally thrown into every aspect of French cooking.

What first got you interested in making butter?

Having worked as a chef for a few years, I knew how much of a necessity it is in the kitchen, but my world was turned on its head when I started at Fäviken (Magnus Nilsson’s two Michelin-starred restaurant) in Sweden. The butter was so—well—buttery! That’s where my butter journey really began, and my fascination with the art of capturing the moment that a product has maximal flavor, or fermenting it to achieve this: peas plucked straight from the pod in their ultimate prime, cattle that’s carefully aged until it tastes incredibly beefy, or sauerkraut that’s insanely “cabbage-y” are good examples.

Is focusing just on butter dramatically different from working as a chef? What do you miss about being a chef?

I feel as though my cooking career has embedded in me the importance of focusing on ingredients, their characteristics and their quality. In those first jobs in London, a massive variety of ingredients was available and abundant, and the focus was on evoking surprise from and deliciousness for the diner through that variety and the resulting flavors. In contrast, when I moved to Sweden, the focus switched to harnessing and creating as much flavor as possible from each and every ingredient around you, even though there might not be many! That transition’s made me something of a minimalist, but it’s a solid fact—underlined by my time at Fäviken—that a dish can only ever be as good as the ingredients it’s made from.

How do you go about “designing” a new butter? What are your aims, what’s the process you go through?

I don’t think you design a new butter, “Butter” by definition—for me at least—unless specified, refers simply to the solid fat that can be separated from cow’s milk. My single aim is to make that solid yellow fat taste as intensely buttery as possible.

Was designing your butter like creating a dish for a restaurant?

Not really! For me, a dish is defined by having multiple components, whereas with my butter, I am focusing all my efforts to make this single component perform at its absolute peak.

What’s your current butter-making set up? What are the sights and sounds: I know you’re a big Sigur Ros fan, do you listen to them while making your butter?

Just over two years ago, I designed and built a kitchen cabin on Lords Farm in Oxfordshire with the sole goal of making butter in it. I have a large French-style churn, and great refrigeration and fermentation capacity. The only downfall of planning it so efficiently was that I didn’t treat myself to windows, so I don’t see the beautiful farm landscape that I’m surrounded by; just yellow, all day, everyday. But I love it.

I am a huge Sigur Ros fan but often keep the music a little more upbeat, say Paul Simon, when I’m being productive and not fermenting.

And what’s your workflow like?

It’s top secret!

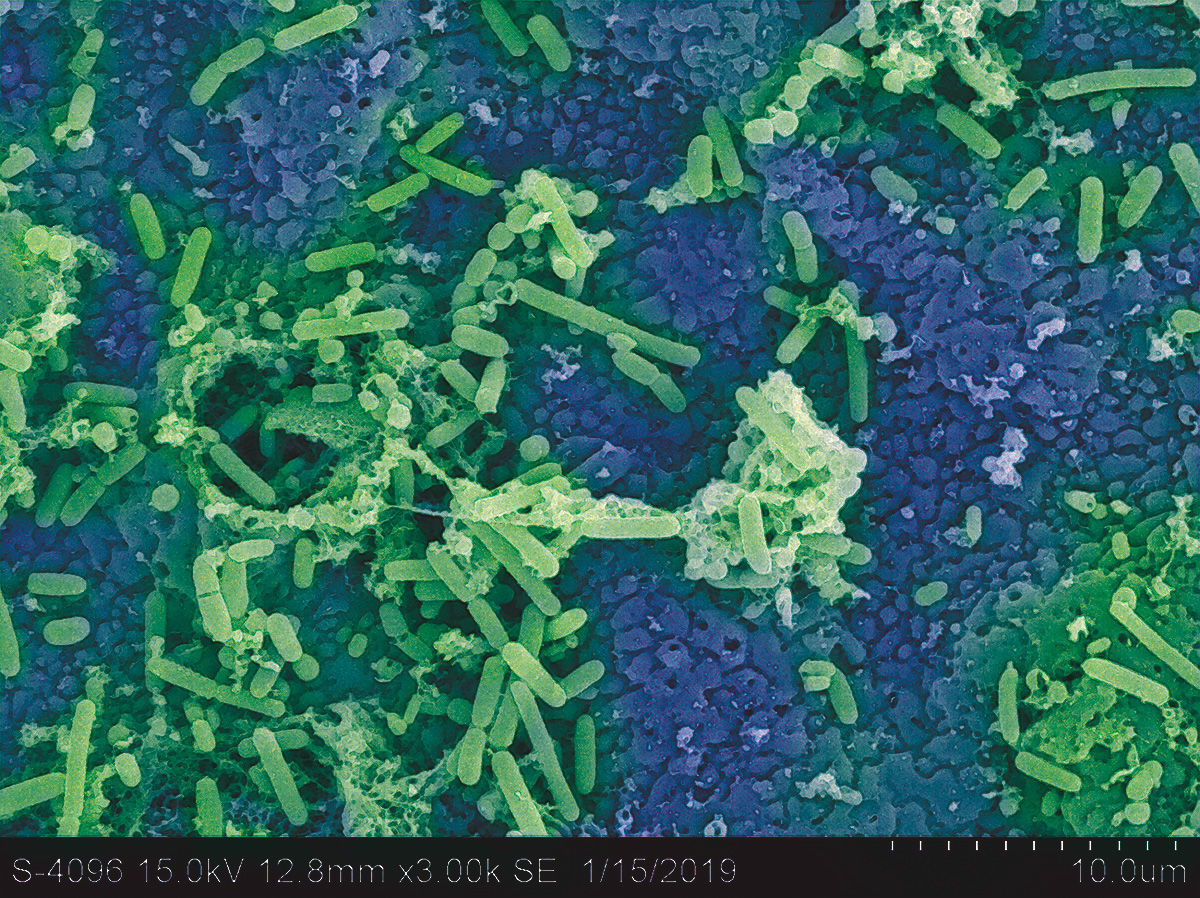

No I’m kidding…Early Monday morning my cream is delivered from a select few Jersey herd farms nearby: I use unhomogenized, pasteurised cream so the particular lactic acid bacteria I ferment it with can produce the specific flavor I want: it’s like a painter starting with a clean canvas. As soon as it arrives, I begin fermenting it in a large tank. The inoculation period usually lasts up to two hours, then the cream is moved to vats and kept at a slightly lower temperature until it’s churned, 158 hours later, on Sunday evening.

Tuesdays, I deep clean the cabin, and shape, portion and package deliveries for the following day. Wednesdays, I deliver to Warwickshire and Nottingham, send butter via courier to the South, Scotland and Newcastle, and, if I get chance, catch up on emails and accounting! Thursdays, I prep more deliveries, which I deliver to Oxfordshire, Buckinghamshire and Gloucestershire on Friday. On Saturday, I take the rest down to London and sell the butter at Druid St Market, just south of the river. Sundays, I’m back on the farm, churning the cream once it’s reached peak flavor and hand-salting the resulting butter.

What’s your favourite type of cream and why?

Whatever’s closest to me: I believe that terroir plays a huge emotional role on a diner, so I will always prioritise cream from cows that are closest, and that have the highest ability to digest beta-carotene and produce butterfat-rich milk: that creates the most vivid yellow butter. Lucky for me, there are Jersey herds local to me.

And your favorite bacteria?

Now that is top secret!

Seasonality has become a big buzzword in recent year, but most of us don’t see its effects in the dairy products we consume most often. Does it make a big difference?

Everything a cow grazes effects her milk output, be it from the beautiful meadow flowers, abundant in fields in spring and summer, to the grains and silage (fermented grass) that are usually available to cows throughout the wetter seasons, which they pretty much stampede over to get to! These differences emerge noticeably—in color and flavor— the way I, and others like me, work.

Aside from your own work, what’s the best butter you’ve eaten, or best butter experience you’ve had?

The butter at Fäviken is phenomenal.